[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Union’s ability to maintain control of Fort Monroe, Va., during the secession crisis provided the Federals with an important strategic toehold in Confederate territory. Not only could Fort Monroe, located on the very tip of the Virginia Peninsula guarding the lower Chesapeake Bay and the Hampton Roads harbor, support operations down the Southern coast by the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, it also provided a springboard for a Union advance against the Confederate capital at Richmond, only 80 miles away. Fort Monroe, known as the “Key to the South,” quickly overflowed with Federal soldiers. When Maj. Gen. Benjamin Franklin Butler, a Massachusetts lawyer, politician and militia general, assumed command, he became the first Union commander to plan a strike on Richmond via the Peninsula. By early June 1861, the Federals had occupied the town of Hampton and had built two additional camps—Camp Hamilton just outside the walls of Fort Monroe and Camp Butler on Newport News Point overlooking the mouth of the James River. Butler’s soldiers were ranging beyond Newmarket Creek (the southwest branch of the Back River), and the Confederates appeared unable to counter the Federal aggression.

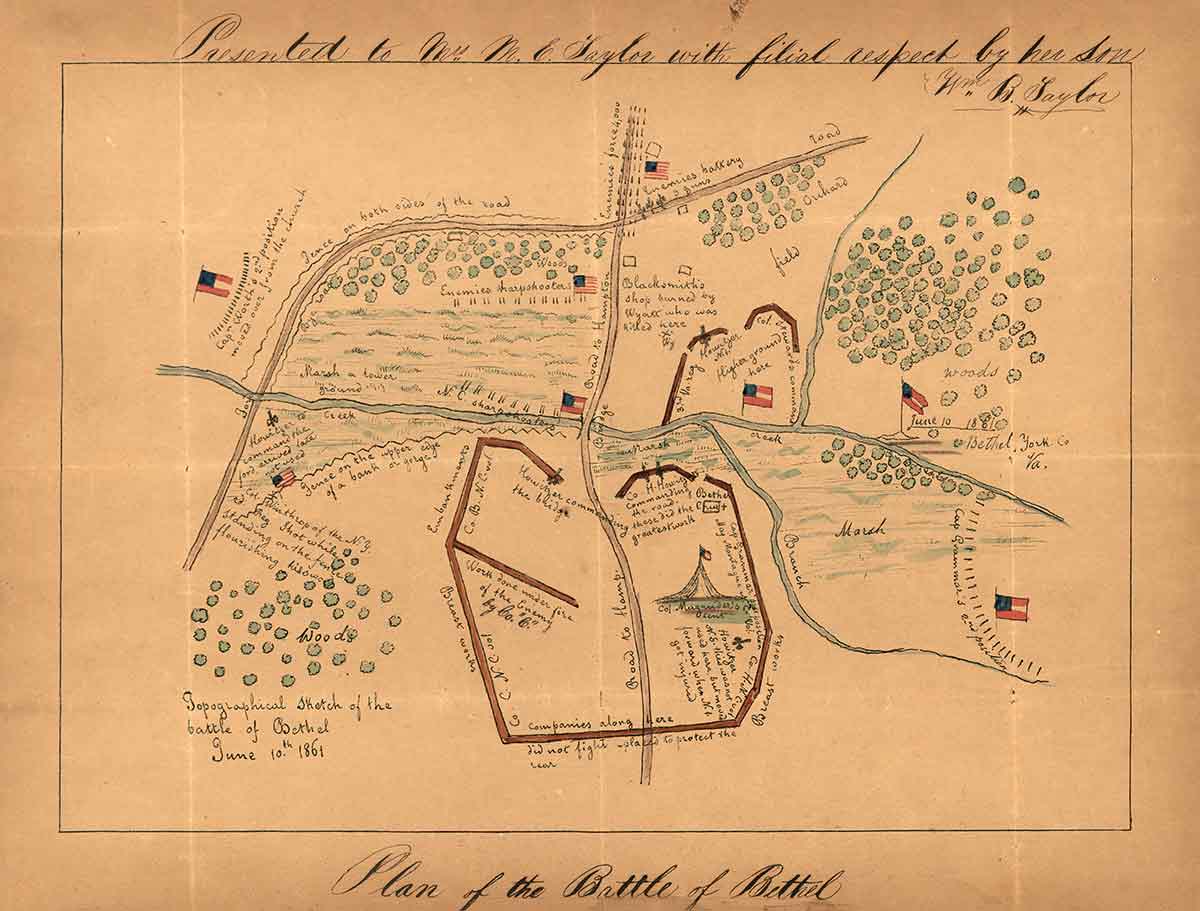

When Confederate Colonel John Bankhead Magruder was assigned to take command at Yorktown, he immediately surveyed the Peninsula to ascertain how best to defend this approach to Richmond. Magruder, a bon vivant and raconteur nicknamed “Prince John” for his courtly manners and lavish dress, was an 1830 West Point graduate and hero of the Mexican War. He knew that he needed time to build a comprehensive defensive system to defend against any Union advance. He selected Big Bethel Church, located at the Hampton–York Highway’s crossing of the northwest branch of the Back River (also known as Brick Kiln Creek) to bait Butler into an attack. Colonel Daniel Harvey Hill, a West Pointer, Mexican War hero, author, and future Confederate lieutenant general, was sent by Magruder to Bethel to construct earthworks to block against any Union movement. Magruder arrived on June 9 and assumed overall command of the 1,400 Confederates.

The Federals, meanwhile, had not been idle. Butler continued to receive reinforcements and began probing beyond Newmarket Creek. Several minor clashes occurred in early June, as the no-man’s land between the Back River’s northwest and southwest branches was now hotly contested. Butler became aware of the Confederate presence at Big Bethel as well as nearby Little Bethel Church, and was convinced he had to make a strike and hopefully destroy the enemy forces there. He planned a night march followed by a surprise attack, using troops from Camp Hamilton and Camp Butler.

Everything went wrong. The available maps were outdated, and the plan failed pretty much from the beginning. Near Little Bethel on June 10, the 7th New York came upon the 3rd New York and began firing, in what would be the first recorded friendly fire incident of the Civil War. It also alerted the Confederates of the Union advance. Union Brig. Gen. Ebenezer W. Peirce, in command of the nearly 4,000 troops, called a “council of war.” Although Peirce knew the element of surprise had been lost, he ordered his men to march on to Big Bethel.

Captain Judson Kilpatrick’s company of the 5th New York (Duryée’s Zouaves) was the first to arrive on the battlefield. After an exchange of artillery fire between Major George Wythe Randolph’s two batteries of the Richmond Howitzers and Lieutenant John T. Greble’s B Battery, 2nd U.S. Artillery, the Union launched several piecemeal attacks against a one-gun fortified Confederate position. Even though the 5th New York was able to capture the position briefly, it was quickly forced to retire under pressure from elements of the 1st North Carolina. One final assault against the main Confederate redoubt was organized by Major Theodore W. Winthrop, a Yale University graduate, ardent abolitionist, and General Butler’s military secretary. Winthrop led elements of the 1st Vermont and 4th Massachusetts across a ford. The 1st North Carolina repulsed the initial attack. When Northrup tried to rally his men by standing on a log and waving his sword, he was shot and killed—quite possibly by African-American Sam Ashe, the servant of an officer in the 1st North Carolina. The battle was over, and the Federals, chased by Major John Bell Hood’s Peninsula Cavalry, rushed to safety beyond Newmarket Creek Bridge.

Big Bethel was a baptism of fire for a nation newly involved in civil war. The soldiers who served at Bethel would never forget the rude awakening of shells bursting among the smartly clad Zouaves or how Henry Lawson Wyatt of Tarboro, N.C., lay lifeless upon the field. Confederate Benjamin Huske remembered that the “scene was…horrible beyond description, men with limbs shot off, brains oozing out and every imaginable horror.” Those who were there quickly realized that the war would not be filled just with parades, and it would not be over before Christmas. All feared it would now be a bloody, desperate affair.

The victorious Confederates wandered about the battlefield and shared stories about their roles in the engagement. Huske was struck by the bodies of the slain Federals, and was particularly touched by Winthrop’s lifeless body. When he examined the slain major’s watch, he found pictures of two lovely women inside and thought that the “death of that poor officer affected me more than anything else, for I knew that there was one home whose light had gone out.

“Great God! Avert the horrors of this civil war! That we should conquer was all for me while it lasted, a man’s blood gets up and he doesn’t mind danger. But when the time of action is passed, we feel the truth of what [Britain’s Duke of] Wellington said, ‘But one thing is more terrible than victory, and that is defeat.’”

While these souls were truly touched by the pathos of war, others ventured through the Union jetsam strewn across the battlefield. Many retained souvenirs or found more serviceable equipment. Some soldiers quickly wrote home to their loved ones reflecting about the great victory and how they missed death by inches. Captain Egbert Ross wrote, “I saw six Zouaves take deliberate aim at me and fire but fortunately they missed me.” Recounted Huske excitedly: “Gracious! How the balls showered around us….[Y]ou can form no idea how they hissed and struck just like a shower of hot stones falling into the water.”

Despite these close calls, most Confederates were in “high glee” after the battle. D.H. Hill reported that his soldiers “seemed to enjoy it as much as boys rabbit-shooting.” B.M. Hord later remembered that the battle “reminded me more of a lot of boys fighting a bumblebee nest than a real battle.”

Southerners rejoiced over the victory at Big Bethel, and laurels were spread everywhere. The one Confederate killed, Private Henry Lawson Wyatt, achieved martyrdom. He was the first Confederate enlisted soldier killed in battle, and as Magruder later wrote, “Too much praise cannot be bestowed upon the heroic soldier we lost.”

Magruder lauded all of the officers and men who had served at Big Bethel. “North Carolinians! You have covered yourself with glory,” Prince John declared, “not only as undaunted in the presence of an overwhelming force bearing yourself with bravery restless but above all with a perfection of discipline in an exciting that was unequaled.” Magruder also noted how units like the Wythe Rifles had behaved with gallantry, and acknowledged the outstanding service of the Richmond Howitzers. Major Randolph, Magruder proclaimed, “has no superior as an artillerist in any country,” and “the victory was partially credited to the ‘skill and gallantry’ of the Richmond Howitzers.”

It was Magruder, however, who would be accorded most of the glory for the victory. President Jefferson Davis called the battle a “glorious victory,” and Robert E. Lee expressed with pleasure “my gratification at the gallant conduct of the men under your command and approbation of the dispositions made by you, resulting as they did, in the rout of the enemy.” Southern newspapers rejoiced over Magruder’s reputation as “the picture of the Virginia gentleman, the frank and manly representative of the chivalry of the dear Old Dominion.” Magruder was placed in the pantheon of Southern heroes with P.G.T. Beauregard and called “every inch a King.” Proclaimed one ballad: “He’s the hero for our times, the furious fighting Johnny B. Magruder.”

On June 17, exactly one week after the battle, Magruder was promoted to brigadier general. The fame seemed to fall upon him naturally, and in every fashion he strove to live up to the honor bestowed upon him. His impressive nature, dramatic flair, and strategic sense had given the South its first victory on the field of battle.

Big Bethel was a complete failure for the Union, and the Northern newspapers were harsh critics. One song was written to the tune of “Yankee Doodle” that epitomized the humiliating defeat:

Butler and I went out from Camp

At Bethel to make a battle

And then the Southerns whip’t us back

Just like a drove of cattle

Come throw your swords and muskets down

You do not find them handy

Although the Yankees cannot fight

At running, they’re the dandy.

Shame was felt throughout the North, even though many of the Union officers involved in the fight endeavored to lessen the engagement’s impact. Colonel Joseph Carr of the 2nd New York Infantry believed the “disastrous fight at Big Bethel” was of no importance. Carr considered Bethel a “battle we may scarce term it.” The future major general believed that neither the Union officers nor men were prepared to conduct such an operation: “To the want of experience and confidence a great measure of the failure at Big Bethel may be attributed.” “Save as an encouragement to the Confederates,” Carr concluded, Big Bethel “had no important result.”

Nevertheless, the Union ineptitude during the battle required that a scapegoat be found. Butler was blamed for ordering his troops into battle with poor intelligence and for remaining at Fort Monroe during the battle. Future Gettysburg icon Gouverneur Warren, who served as lieutenant colonel of Duryée’s Zouaves at Bethel, later reported to the Congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War that the plan was “from the very beginning evolved like a failure.” Warren made sure to point out that the maps, which dated from 1819, were all wrong. The complicated advance “was planned for a night attack with very new troops, some of them had never been taught even to load and fire.” The planning was poor and the leadership abysmal.

Of course, Butler strove to deflect all of the criticism from himself. His confirmation as a major general of volunteers was at risk due to the public outcry. Butler blamed it all on Peirce. He noted that no one had criticized the plan when it was developed, and that he had no choice but to place the strike against Big Bethel under the command of his senior brigadier general. While Butler conceded that the plan evolved upon the battlefield, he maintained that the various efforts to strike at the Confederates were generally uncoordinated and disorganized, Obviously, Ebenezer Peirce received most of the blame for the disaster. He reportedly was confused during the entire operation. “There was no uniformity of action anywhere,” noted Captain Charles Bartlett of Duryée’s Zouaves. According to fellow Zouave Karl Ahrendt, Peirce hid “behind a tree shivering with fright.” Peirce, Ahrendt insisted, was a “slack and decrepit individual who would be far better suited for enjoying the comforts of a house and garden than leading a soldier’s life.” Major Peter Washburn later wrote about the lack of battlefield leadership, stating, “We had no head….All the different commanders behaved nobly; but there was no reconnaissance, no plan of attack, and no concert of action….A little military skill in the General, a little regard to the simplest rules of attack would have rendered our charge successful. As it was, it was a failure—an egregious blunder.”

Peirce lost control of his strike force of Massachusetts militiamen following the friendly fire incident and apparently never gained effective command again even when striving to organize an orderly retreat. The general was labeled incompetent and mustered out of the Army after his regiment’s 90-day enlistment expired. (Peirce returned to the fighting in December 1861, however, as colonel of the 29th Massachusetts Infantry and saw action until November 1864 before being mustered out during the Siege of Petersburg. He lost his right arm during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign.)

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Ebenezer Peirce was a ‘slack and decrepit individual who would be far better suited for enjoying the comforts of a house and garden than leading a soldier’s life’

-Zouave Karl Ahrendt[/quote]

The New York Times tried to salvage some honor out of the defeat and called the Union troops courageous as “they fought both friend and foe alike with equal resolution and only retired after exhausting their ammunition in the face of a powerful enemy.” The friendly fire incident prompted a brief debate in the New York newspapers as to who was to blame for this deadly mistake. Louis Schaffner, adjutant of the German-speaking 7th New York Infantry, believed the confusion was caused by several units in the 3rd New York wearing uniforms similar to the enemy. Furthermore, Schaffner noted that the mounted commanders and their staff (mistaken for enemy cavalry), as well as failure to inform the 7th New York (Steuben Regiment) about orders to wear white armbands and the designation of a password, caused the New Yorkers to fire into their compatriots.

The debate ended with the recognition that it was simply a misfortunate affair based on an ill-conceived plan.

Northern newspapers lauded all of the officers and men at Big Bethel. Theodore Winthrop and John T. Greble were lionized for their valor and sacrifice. Winthrop, who had been told by Butler to “Be Bold! Be Bold but not too Bold,” almost won the day for the Union with his bravery. And Greble, the Regular Army commander of the Union battery at Bethel, covered the Federal retreat until he was killed by shell fragments. He was the first West Pointer to die in the war.

Other officers and men received accolades for their devotion to duty during the battle. Peirce made special reference “to the gallant and soldier-like conduct of Colonel Townsend, who was indefatigable in encouraging his men and leading them in the hottest…action.” He also noted that “Colonel Carr, in covering the retreat, showed himself a good soldier and willing to do his duty.”

Warren was also commended for remaining on the battlefield and recovering the dead and wounded directly after the engagement. And Judson Kilpatrick of Duryée’s Zouaves attained virtual hero status for his involvement. The battle was filled with difficulties and impossibilities for the Union soldiers. Despite the individual bravery, the Federal plan and execution could not overwhelm the superior Confederate leadership, élan, and defensive preparations.

Big Bethel had major consequences for the Union and Confederate forces on the Peninsula. Over the next 10 months the Federals were content to control the very tip of the Peninsula below Newmarket Creek. The Union was able to use this position to protect the lower Chesapeake Bay as a base for the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron for operations against sites like Port Royal Sound and Roanoke Island. Furthermore, control of the lower Peninsula enabled Union troops to welcome more escaped slaves as contraband of war. Contraband communities and schools were created and thrived. The Confederates, despite Magruder’s wish to sweep the Federals into the sea, were unable to contest the Union Department of Virginia’s control of the lower Virginia Peninsula. This circumstance would lead to the burning of Hampton on August 7, 1861, and the use of Fort Monroe as a base for McClellan’s 1862 Peninsula Campaign.

The Confederate victory nevertheless blocked the first Union attempt at an advance on Richmond via the Peninsula. The battle lines were drawn, and the Confederates maintained control of the Peninsula north of Brick Kiln Creek. The area between the northwest and southwest branches of the Back River became no-man’s land. This strategic situation allowed the Confederates to construct an in-depth defensive system that would eventually befuddle McClellan during the early stages of the Peninsula Campaign. Magruder’s defensive alignment helped protect the industrial centers of Norfolk and Portsmouth and allowed the Confederates freedom to construct their famed ironclad Virginia. Furthermore, it kept open access to the region’s rich agricultural region used to support their armies in Virginia.

Big Bethel eventually faded in importance nationally. Even though it retained its status as the war’s first land battle, it was essentially merely a skirmish and would be overshadowed by bloody and decisive engagements to come, such as at First Manassas and Shiloh. Nevertheless, Bethel had a major impact on both sides. The Union men who were there gained battlefield experience and the recognition that it would require a serious commitment to ensure preservation of the Union. “I’ve seen enough to satisfy me that warfare ain’t play,” one anonymous New Yorker wrote.

In turn, the Confederate victory at Big Bethel raised enthusiasm for the war and reinforced the myth that one Southerner could defeat at least four or five Northerners. Consequently, they felt the war could indeed be won. Southern newspapers chimed in with their praise. The Richmond Whig proclaimed, “The rush, the dash, the élan of our boys was…the great and distinguishing feature of the affair….Their dashing bearing, in the face of four times their number, will inspire a spirit of emulation among all of our forces, and lead to the rout of the invaders wherever they show themselves.” The Petersburg Express lauded all “in this first pitched battle on Virginia soil in behalf of Southern rights and independence.”

Nearly 6,000 men took part in the engagement. The casualties were low: The Federals lost 76 men, 18 killed (two of those killed and 19 of the wounded were friendly fire casualties in the 3rd and 7th New York). The Confederates lost only one killed and nine wounded. Many of the survivors would go on to greater acclaim, and others would serve their enlistments and go home. All of them would never forget their first blood-letting that hot day at Big Bethel Church.

John V. Quarstein, a regular America’s Civil War contributor, is director emeritus of the USS Monitor Center in Newport News, Va., not too far from the ground upon which the Battle of Big Bethel was fought in June 1861.