‘ We found the enemy with about from three to five thousand men posted in a strong position,’ Union Captain Judson Kilpatrick wrote of the June 10, 1861, Battle of Big Bethel, Virginia. ‘Captains Winslow, Bartlett, and myself charged with our commands in front. The enemy were forced out of the first battery, all the forces were rapidly advancing…everything promised a speedy victory, when we were ordered to fall back.’

A few days later, the New York Times published Kilpatrick’s stirring report of this early Civil War clash. Northerners eagerly christened him a hero. Here, it seemed, was a man of action–the type of fighter who would help crush the rebellion in short order.

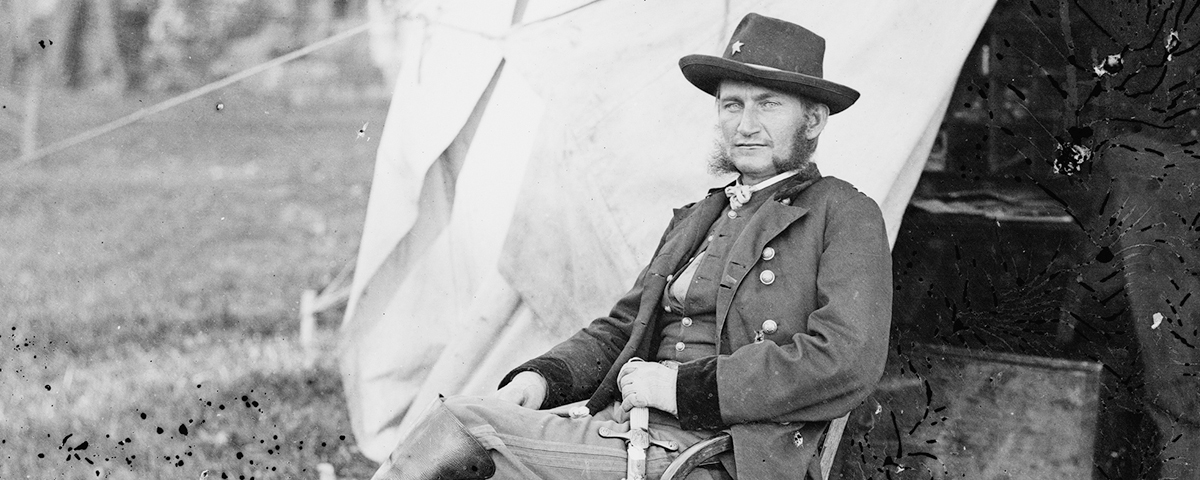

Kilpatrick’s admirers might have hesitated to drape him in glory if they had gotten a good look at him. He was not quite the image of the consummate hero, with his long, pointed nose, scraggly hair, and frail, stooped body. Furthermore, lurking behind his bravado was a glory hound willing to say anything to make himself look good. In truth, the fight at Big Bethel had been an ugly, confused skirmish, with little opportunity for glory. Union Colonel Joseph B. Carr called it ‘the disastrous fight at Big Bethel–battle we scarce may term it.’ Kilpatrick, in fact, suffered an embarrassing minor wound to his buttocks. How this occurred while he was supposedly charging the Confederate position, Kilpatrick did not say. His performance during this brief campaign established a pattern of behavior that would earn him few admirers, many enemies, and–inexplicably–rapid promotions during the Civil War.

Kilpatrick’s mere presence at Big Bethel was a testament to his ability to cultivate influential friends. Born on a farm in Deckertown, New Jersey, in 1836, he had decided early on what he wanted out of life. ‘I will be an outstanding soldier,’ he would boast, ‘and then go on to be Governor of New Jersey, and eventually president of these United States.’ It seemed simple enough.

In 1855, the 19-year-old with big plans applied for admission to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York. He was rejected. Not to be denied, Kilpatrick went to work for New Jersey Congressman George Vail, who was up for reelection. Kilpatrick ‘went from village to village, haranguing the electors,’ the Comte de Paris wrote in his 1875 study History of the Civil War in America. Vail was reelected and thanked Kilpatrick by appointing him to the academy.

At West Point, Kilpatrick made a new beginning, dropping his first name, Hugh, in favor of his middle name, Judson. The upper classmen immediately went to work hazing the odd-looking plebe, but the 5′ 5′, 140-pound Kilpatrick did not hesitate to fight back with his fists. He was a good student, an avid debater, and often appeared in plays the academy produced. His conduct, too, was exemplary. In his five years at West Point, he earned only 40 demerits, none of them in his last two terms.

Kilpatrick had a powerful motivation for behaving–good conduct meant freedom to leave campus on weekends. The cadet had fallen for Alice Shailer, niece of a prominent New York politician. At Kilpatrick’s graduation on May 6, 1861, one of his friends approached her. ‘Kill is going to the field and may not return,’ he said. ‘Better get married now.’ The two wed that evening. After a honeymoon of a single night, Kilpatrick headed for Washington and the Civil War.

The outbreak of war was a stroke of good fortune for ambitious young soldiers. Kilpatrick sized up his best opportunities for advancement. Graduating 17th in a class of 45, he had received a commission as a second lieutenant in the 1st U.S. Artillery, but he saw the new volunteer army as his best bet. He asked his mathematics instructor at the academy, Gouverneur K. Warren, to recommend him for a post with a New York regiment. Warren came through; Kilpatrick was commissioned captain of Company H, 5th New York Infantry.

After a month of training at Fortress Monroe on the tip of the Virginia Peninsula, east of Richmond, the 5th was ready for action. Major General Benjamin Butler, commanding the Department of Virginia, sent parts of seven regiments under Brigadier General Ebenezer W. Pierce to attack the Confederate outpost at Big Bethel. The excursion–Kilpatrick’s self-congratulatory account notwithstanding– proved a Union embarrassment. After suffering 76 casualties in a brief attempt to flank the Rebels–who were actually outnumbered nearly two-to-one–Pierce ordered a retreat. Kilpatrick, with his bleeding posterior, struggled back to camp on a mule. ‘Everything was utterly mismanaged,’ Butler later wrote.

Colonel Abram Duryée, the commander of the 5th New York, could not have been pleased when Kilpatrick offered his skewed battle report to the press. Still, Kilpatrick’s name was now well known, and when Duryée was told to dispatch an officer to New York City to recruit more men for the regiment, he sent Kilpatrick. In New York, Kilpatrick found himself competing for recruits with Colonel J. Mansfield Davies, who was organizing a cavalry regiment. The two quickly struck a deal. Instead of enrolling men into the infantry, Kilpatrick signed them up as horsemen. When Davies reached his quota, he would make Kilpatrick a lieutenant colonel.

Duryée soon learned of this scheme and ordered Kilpatrick to return to Fortress Monroe. Kilpatrick instead applied for sick leave, awaiting the payoff from his deal with Davies. Duryée was disgusted and suggested to his superiors that his derelict subordinate be replaced, to ‘relieve us from what has been…an embarrassment.’ On September 25, 1861, Davies fulfilled his promise and made Kilpatrick lieutenant colonel of his ‘Harris Light Cavalry,’ the 2d New York.

While Kilpatrick’s men lived and trained in a camp outside Washington, D.C., Kilpatrick took up residence at Willard’s Hotel in the city, where he mingled with the politicians who might advance his career. To help pay for his expensive room, Kilpatrick cut a deal with crooked Union sutlers. One, Hiram C. Hull, later testified, ‘I paid Lieut. Colonel Kilpatrick twenty dollars in gold’ for steering an army contract his way.

Late in the spring of 1862, Major General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac marched into Virginia. President Abraham Lincoln gave McClellan’s 1st Corps to Brigadier General Irvin McDowell, with orders to fend off any Confederate force that threatened Washington. The 2d Cavalry joined McDowell, with Kilpatrick acting as commander in place of the ill Davies, who would never return to the field. As he moved into Rebel territory, Kilpatrick came up with a number of backdoor schemes to line his pockets. He confiscated horses from local farms for the Union army, but kept the best mounts for himself and sold them in the North. He stole tobacco from local plantations, which he passed on to the sutlers to sell to the troops. Despite receiving ‘one-third of all monies accrued,’ Kilpatrick was still borrowing money from the sutlers, a breach of army regulations.

Kilpatrick had little opportunity to distinguish himself while McClellan plodded toward Richmond. When a chance did come, though, he slipped up. In late May, Confederate Major General Thomas J. ‘Stonewall’ Jackson plowed into the Shenandoah Valley, routing one Union opponent after another and threatening the Yankee capital. Kilpatrick was sent to the Richmond area to scout Confederate movements. On May 28, Kilpatrick reported that 15,000 Rebels had been sent to reinforce Jackson. He had been duped. The misinformation kept McDowell’s corps anchored near Washington, while Jackson slipped from the valley unmolested.

Between June 25 and July 1, Jackson and General Robert E. Lee, the new commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, confronted McClellan in the Seven Days’ Battles. McClellan’s troops fought well in these battles, but the cautious, timid, Union commander retreated anyway, giving up the offensive. Frustrated, Lincoln fused three independent commands, including McDowell’s corps, into the new Army of Virginia, led by Major General John Pope. He hoped for better results from this new army. Kilpatrick’s 2d New York joined Brigadier General George D. Bayard’s cavalry brigade, attached to Brigadier General Rufus King’s infantry division, in Pope’s army.

The bombastic but aggressive Pope gave the cavalry a fighting role. On July 19, Kilpatrick’s 2d New York left Falmouth for Beaver Dam Station on the Virginia Central Railroad. The Yankee riders burned the depot and captured the one Confederate they found there–a then-unknown captain named John S. Mosby. ‘The affair was most successful,’ Pope noted, ‘reflecting high credit upon the commanding officer and his troops.’

Kilpatrick followed up this success by charging into Hanover Junction on July 23. His men burned the depot before Major General J.E.B. Stuart’s Confederate cavalry chased them off. On August 6, the 2d New York joined a raiding party led by Colonel Lysander Cutler that leveled Frederick’s Hall Station. While Kilpatrick’s superiors applauded him, his men began to grumble. ‘Many were confined to their tents [with] saddle boils and lameness,’ Lieutenant Henry C. Meyer recalled. The troopers began to call their aggressive commander ‘Kill-Cavalry.’

Bayard’s cavalry was screening for Pope’s army two weeks later when Stuart’s cavalry approached near Brandy Station. ‘Down came the enemy, charging along the road,’ a New Jersey cavalryman recalled, ‘and Kilpatrick was ordered to meet them.’ The 2d was almost in position when confusion suddenly engulfed the ranks. Before Kilpatrick could realign his men, the 12th Virginia Cavalry crashed into the line and scattered it. Other Rebel units followed up and drove the Yankees from the field.

Two weeks later, Pope sent the cavalry to Thoroughfare Gap to intercept Major General James Longstreet’s Confederate corps. It was too little too late. Longstreet hurried through the gap to link up with Stonewall Jackson at Manassas. On the morning of the 30th, as Pope threw his army at Jackson’s entrenched Rebels, Longstreet slammed into Pope’s exposed flank. The Second Battle of Bull Run ended the same way as the first had a year earlier.

Pope’s beaten army began a rapid withdrawal. As Confederate shells fell indiscriminately among the scurrying Union infantry, Kilpatrick decided to make his presence felt. ‘General McDowell wants the Harris Light to take [that] battery,’ he yelled to his men. ‘Draw sabers!’ Kilpatrick watched from relative safety as his troopers cantered toward a Rebel battery hidden in the darkness. Suddenly, the Rebel guns lit up the air, unhorsing several Yankees and scattering the rest. ‘The charge was a blunder,’ Lieutenant Meyer wrote. ‘Kilpatrick was severely criticized in the regiment for it.’

Pope was relieved and his Army of Virginia dispersed. Lee promptly moved north into Maryland, with McClellan–back in charge of the reassembled Army of the Potomac–on his heels. As the 2d New York rested near Washington, Kilpatrick again plundered the Virginia countryside. When he sold two mules ‘borrowed’ from a local farmer, however, the victim filed a complaint with the provost marshal. The subsequent investigation exposed all of Kilpatrick’s crooked schemes, and he was locked up in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington.

‘Affidavits,’ Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, concluded, ‘…leave little question of [Kilpatrick’s] guilt.’ The defendant, however, was one of the few Union cavalry leaders who took on Confederate horsemen. So, on January 21, 1863, after three months in jail, he was released.

Kilpatrick returned to a new and improved cavalry organization. Major General Joseph Hooker, now commanding the Army of the Potomac, had combined the horse units wasting away alongside infantry divisions into a single, powerful corps of 9,000 horsemen, led by Brigadier General George Stoneman. Kilpatrick, who was now a colonel, was given command of the 1st Brigade in Brigadier General David McMurtrie Gregg’s 3d Division.

In April, Hooker began his campaign against Lee. He sent Stoneman out on a preliminary raid, with orders to do ‘a vast amount of mischief.’ The cavalry chief divided his 4,000 riders into several raiding parties and sent them out. Kilpatrick set to work with his old 2d New York and spent the next five days tearing up track, burning rail depots, and destroying rail cars and telegraph lines. At one point he rode within two miles of Richmond, where his little force surprised and captured a group of Rebel horsemen. When the regiment rode into the Federal garrison at Gloucester Point, the men were cheered as ‘lions of the day.’ It was probably Kilpatrick’s best moment of the war.

Overall, however, Stoneman’s raid yielded little success. ‘With the exception of Kilpatrick’s operations,’ Hooker noted, ‘the raid [did not] amount to much.’ Worse for Hooker, while his horsemen wasted their time to the south, Lee and Jackson had surprised and beat his army at Chancellorsville on May 1-4.

Lee followed up his victory by invading the North for the second time. Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton replaced Stoneman and set off in pursuit. Before dawn on June 9, 1863, Pleasonton’s Union cavalry surprised Stuart’s Confederate horsemen at Brandy Station, Virginia. Brigadier General John Buford crossed the Rappahannock River and hit Stuart from the north. Stuart set up his defense–led by William E. ‘Grumble’ Jones, Wade Hampton, and W.H.F. ‘Rooney’ Lee–around the base of a rise called Fleetwood Hill. Meanwhile, Gregg, with Kilpatrick’s brigade in tow, crossed the river at Kelly’s Ford, and approached the scene from the south.

Gregg sent Colonel Percy Wyndham’s brigade to surprise Stuart from behind. He held Kilpatrick in reserve in woods just south of the nearby Orange and Alexandria Railroad tracks. Wyndham fought his way to the top of Fleetwood Hill, where his men tangled with Confederate riders in dust so thick, a 1st Pennsylvania trooper recalled, that ‘we could not tell friend from foe.’ Gregg ordered Kilpatrick to support Wyndham. Kilpatrick, however, had inexplicably failed to align his brigade. During the delay, Wyndham was driven from the hill.

When Kilpatrick finally moved, he compounded his mistake by sending his three regiments forward in echelon, rather than as one body. Within minutes, both the 10th and 2d New York were shattered by Rebel charges and sent ‘floating off like feathers on the wind.’ Kilpatrick was shocked. He turned to 1st Maine Colonel Calvin S. Douty. ‘Colonel Douty,’ Kilpatrick asked, ‘What can you do?’

‘I can drive the Rebels,’ came the reply.

‘Go in and do it!’ Kilpatrick said.

The 1st Maine charged up the hill, smashing through the 1st South Carolina on the way. Douty advanced more than a mile before realizing he was cut off from support. As he fought his way back toward the railroad tracks, Kilpatrick sent help. ‘Back, the Harris Light! Back, the Tenth New York!’ he exclaimed. ‘Re-form your squadrons and charge!’ After a series of inconsequential charges and counter-charges, the Yankees pulled back from the heights. Pleasonton retired from the field in the late afternoon.

At a crucial point in this pivotal battle–one that might have given the improving Union cavalry its first clear-cut victory over Stuart–Kilpatrick had failed. His name was conspicuously absent from the list of officers Pleasonton cited for gallantry. Nevertheless, probably because of his role in Stoneman’s recent operations, Kilpatrick became a brigadier general on June 14.

On June 10, Lee started his infantry northward down the Shenandoah Valley. Hooker, still unsure of Lee’s intentions, sent his cavalry west to gather intelligence. Kilpatrick led the way. As he approached Aldie on June 17, he spotted Rebel troops about the village. ‘Kilpatrick’s standing order,’ a newspaperman wrote, ‘was ‘Charge god damn ’em,’ whether they were five or five thousand.’ This day was no exception. Without bothering to determine the enemy’s strength or position, he sent the 1st Massachusetts forward with sabers flashing.

The Confederates fled out of town, bearing right at a fork in the road and drawing the Union riders after them into an ambush. ‘My poor men were just slaughtered,’ Captain Charles Francis Adams of the 1st Massachusetts recalled. Kilpatrick next called the 2d New York to the front, gave a fiery speech, and sent them down the left fork. Again, the Yankee horsemen rode into an ambush. More than 100 of them fell in a deadly crossfire.

Kilpatrick was devastated. ‘His countenance was dejected and sad,’ a 1st Maine trooper recalled. ‘The fire in his eyes was gone. He looked indeed a ‘ruined man.” He made one more attempt to dislodge the Rebels. He assembled the 1st Maine, and for one of the few times in his career, personally led a charge against the enemy. The Confederates were driven back into the gaps of the Blue Ridge, but they had kept the Federal troopers from spotting Lee’s infantry.

As Lee moved into the North, the command of the Army of the Potomac changed again. On June 28, Major General George Gordon Meade replaced Hooker, and he immediately shook up the cavalry. Despite his recent blunders, Kilpatrick was given command of the Cavalry Corps’ 3d division. Newly minted Brigadier Generals Elon J. Farnsworth and George Armstrong Custer would lead Kilpatrick’s two brigades.

On June 30, Kilpatrick rode in the van of his division as it trotted through Hanover, Pennsylvania. At about 10:00 a.m., just as Farnsworth’s troops were exiting the town, Stuart’s men attacked the rear of the Union column. When Kilpatrick heard firing, he whirled about and galloped wildly back toward Hanover. He arrived just after the fight ended. As Kilpatrick dismounted in the village square, his exhausted horse collapsed and died.

Stuart’s troopers stole away during the night. Kilpatrick advanced cautiously on July 1, ignoring the boom of cannons to his left–the opening salvos of the Battle of Gettysburg. On July 2, Meade sent for Kilpatrick, but the cavalry leader moved so slowly that he did not arrive at the front until noon on July 3. He took up a position on the far left of Meade’s line.

That afternoon, as Pickett’s Charge failed, Kilpatrick thought he saw a chance to be a hero. He ordered Farnsworth to assault the flank of the retreating Confederates.

‘Do you mean it?’ Farnsworth gasped. The ground ahead was heavily wooded and strewn with huge boulders. A mounted charge through that labyrinth would be suicidal.

Incensed by Farnsworth’s response, Kilpatrick sneered, ‘If you are afraid, I’ll lead the charge.’

‘Take that back!’ Farnsworth shouted.

‘Forget it!’ Kilpatrick snapped.

‘I will lead it,’ Farnsworth insisted, so loudly that a nearby Confederate regiment could hear the exchange, ‘but you must take the responsibility.

‘I take the responsibility,’ Kilpatrick replied.

Farnsworth led a column of troopers forward. As he had feared, they were greeted by a hailstorm of minié balls. In minutes the Yankee riders were scrambling desperately to return to their line. Farnsworth, however, lay dead, killed in the last flurry of shots.

On July 5, following the Union victory, Kilpatrick was ordered to harass Lee’s retreat. He attacked the Rebels’ wagon trains that night, but Stuart soon appeared and drove Kilpatrick back to Boonsboro, Maryland, where he stayed for more than a week. On July 13, as the last of the Confederates forded the Potomac into Virginia, Kilpatrick rode to the river. Confederate Major General Henry Heth’s 4,000 men were waiting their turn to cross when Kilpatrick sent two squadrons–just 40 troopers–to charge them. ‘As any competent cavalry officer would foretell,’ one of Buford’s officers later remarked, ‘they were instantly scattered and destroyed.’

Kilpatrick claimed in his report that he had captured a brigade of infantry, two cannon, two caissons, and a large number of small arms. He sent the New York Times a copy of this twisted account, and the editors published his lies. When Lee saw the article, he was so incensed that he wrote a letter of protest to Meade. The Union commander looked to Kilpatrick for an explanation, but he was gone. His wife, who had visited him nine months ago in the Old Capitol Prison, had given birth, and Kilpatrick had gone to see his new son.

Returning to duty on August 5, Kilpatrick found Annie Jones, a teenage harlot, visiting his headquarters at Falmouth, Virginia. The new father immediately talked her into sharing his tent. This was not his first indiscretion. His entourage included several other women, and the word around camp was that their duties went far beyond cooking his meals. Two weeks later, Jones moved in with Custer. Outraged, Kilpatrick had her arrested as a spy and shipped off to the Old Capitol Prison.

In October 1863, Lee advanced north toward Meade. The two armies met at Bristoe Station, Virginia, on the 14th, and after a sharp clash, the Federals emerged victorious. The Rebels retreated and Kilpatrick was sent after them. On the 18th he found Stuart protecting the tail of the Confederate column near Buckland.

Stuart laid a trap for his overeager foe. When the Union horsemen charged, he fell back, luring Kilpatrick after him. Meanwhile Confederate Major General Fitzhugh Lee brought his troopers up from the south to attack the Yankee rear. When Lee arrived, Stuart whirled around and attacked Kilpatrick. Caught in a pincer, the trapped Federals scattered. ‘The rout of the enemy at Buckland,’ Stuart gloated, ‘was the most signal and complete…any cavalry…suffered during the war.’

Kilpatrick was humiliated. His career again seemed ruined, and should have been. At this low point, word came that his wife had died. He rushed east that November for her funeral, came back to his bivouac, and then returned to New York in January for another funeral; his baby son, too, had died.

Such crushing personal losses compounded Kilpatrick’s concerns for his future, and made him ready to try something desperate. He quickly devised a scheme to ride into the Rebel capital and free Yankees confined at the Libby and Belle Island Prisons. Anxious for approval of his plan, he went over the heads of his superiors and appealed directly to Lincoln. Pleasonton and Meade were irritated that Kilpatrick had bypassed them, but Lincoln’s approval forced them to support the raid. Kilpatrick would lead 3,500 riders to Richmond from the north, while Colonel Ulric Dahlgren would take 500 troopers over the James River and approach the Confederate capital from below.

The columns crossed the Rapidan River at dusk on February 28, 1864. On March 1, the raiders reached the outskirts of Richmond. ‘We were so close that we could…count the spires on the churches,’ one recalled.

Up ahead, a handful of old men and young boys manned a bulwark, the only obstacle to Kilpatrick’s riding into Richmond and carrying out his mission. He stopped and listened for the rattle of rifles that would signal Dahlgren’s charge from the south, but heard nothing. He waited for two hours in the icy rain; meanwhile, fear built up in his mind. He thought he saw reinforcements filing into the fort in front of him. When a locomotive whistle blew to his rear, he suspected that an enemy force was arriving to attack him from the north. Kilpatrick suddenly realized he had made no provisions for transporting the prisoners he hoped to liberate. The captives would have to walk about 50 miles to the Union lines.

Kilpatrick lost his nerve. He ordered his men to retire east toward the Chickahominy River. At about 5:00 p.m., Kilpatrick’s riders crossed the river and set up camp near Mechanicsville. ‘Snow was falling,’ a trooper wrote, ‘and it was very dark.’

As he shivered in the cold, Kilpatrick suddenly decided to mount his raid after all. While he waited safely in camp, two small groups would dash into the Confederate capital. One would free the prisoners; the other would kidnap President Jefferson Davis. But just as the men were saddling their horses, a fuss erupted in the Union rear. Wade Hampton, who had been pursuing Kilpatrick for 48 hours, had finally caught up and was attacking. Hampton had just 300 Confederate horsemen with him, but Kilpatrick was not counting noses. He called his 3,500 troopers to mount, and fled east toward Benjamin Butler’s camp at New Kent Court House.

Kilpatrick reached Butler’s lines on March 4, but Dahlgren was not so lucky. His attempt to ride into Richmond had been thwarted, and as he galloped east to rejoin the rest of the Yankee force, he had encountered some home guards, who shot and killed him. Confederate authorities claimed that orders to kill President Davis were found in his pockets. The Union officially claimed that Rebels must have forged the orders.

Meade took the bungled raid as an opportunity to demote Kilpatrick to brigade command and assigned him to serve under his replacement, Brigadier General James H. Wilson. Kilpatrick wanted no part of this purgatory. He requested a transfer to the West, where Major General William T. Sherman was just replacing Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant as chief of the Military Division of Mississippi. Sherman welcomed him. ‘I know that he is a hell of a damned fool,’ Sherman remarked, ‘but that is just the sort of man I want for my cavalry.’ Kilpatrick’s luck continued to hold. On April 16, 1864, he set out for Tennessee.

Sherman was moving southeast out of Chattanooga to confront General Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederates near Dalton, Georgia. Kilpatrick was given a division of cavalry in the Army of the Tennessee, which was maneuvering through the mountains below Dalton to flank the Rebel stronghold. As the army neared the town, Kilpatrick’s force advanced to scout the field. A Southern sharpshooter saw Kilpatrick coming and shot him in the thigh.

While Kilpatrick recuperated at West Point, Sherman and Johnston fought each other steadily toward the outskirts of Atlanta. They were facing each other outside the city on July 23 when Kilpatrick rejoined his command. Sherman wanted the city’s southern supply lines cut off and asked whether Kilpatrick could do it. ‘It’s not only possible,’ Kilpatrick boasted, ‘but comparatively easy.’

Kilpatrick’s division set out on August 18. After a spectacular four-day ride, Kilpatrick reported back to Sherman that his men had ripped up the tracks at Jonesboro and Lovejoy’s Station. He was still talking when a locomotive blew its whistle as it pulled into the city. The Rebels had undone Kilpatrick’s work in just 24 hours.

On August 25, Sherman marched south. His infantry cut the enemy’s supply line once and for all, and on the night of September 2, Confederate General John Bell Hood abandoned the city.

Sherman’s forces soon started on a march from Atlanta toward the Atlantic coast. Along the way, Federal infantry destroyed railroads and burned buildings that had military value, but generally left the civilian populace alone. Kilpatrick’s troopers, however, pillaged one plantation after another. ‘They drove off cows, sheep, and hogs,’ one owner said, ‘took every bushel of corn and fodder, oats and wheat, and burned the house.’ At another farm, Kilpatrick rounded up horses to replace his own worn-out mounts. His men gathered about 500 more animals than they needed, so Kilpatrick ordered the surplus killed. One by one the poor beasts were bashed on the head. The farm owner watched in horror as a mountain of dead horses arose in his yard. ‘My God,’ he gasped, knowing that he could never bury so many animals. ‘I’ll have to move.’

On November 28, Kilpatrick was attacked at Waynesboro by Confederate cavalry under Major General Joseph Wheeler. Rather than stand and fight, Kilpatrick fled west, bringing with him a black prostitute.

Kilpatrick assumed he had outrun Wheeler, so he stopped for the night outside Rock Springs. Just before dawn, Wheeler attacked his camp. Kilpatrick raced outside in his underwear, jumped onto a stray mount, and fled for his life. He left behind his uniform, a gold-hilted sword, two ivory handled pistols, his best horse, and, of course, his mistress.

For the rest of the campaign, Kilpatrick stayed close to the infantry. Sherman’s columns arrived at Savannah, on the coast; by December 21 the port city was in Sherman’s hands. For the six weeks that the Federals stayed in Savannah, they respected private property. Not so Kilpatrick. Encamped to the south near Midway Church in Liberty County, he sent his men to ravage the countryside, foraging daily and visiting the same plantations again and again. ‘There was no use to put things in order,’ one owner stated. ‘Every separate gang ransacked the house afresh.’

Kilpatrick himself was busy with a new mistress, an Oriental laundress named Molly. When Sherman headed north into South Carolina, Molly moved with Kilpatrick. She was pregnant. ‘He has done me so,’ she insisted, ‘and I will stick to him and make him take care of the baby for it is his.’

The cavalry entered Barnwell, South Carolina, on February 6, and burned most of its public buildings. Kilpatrick established his headquarters in a home called ‘Banksia Hall.’ That evening, Kilpatrick held a ‘Nero’ ball for the ladies of the nearby plantations. As they danced to music played by Kilpatrick’s band, his troopers set fire to their homes. ‘It was the bitterest satire I ever witnessed,’ one of Kilpatrick’s officers professed, ‘and justly stained the reputation of Kilpatrick.’

On February 10, Kilpatrick started toward Aiken. He had learned Wheeler’s cavalry was there, and he planned to attack him. As he approached the village, Kilpatrick spotted enemy riders. He immediately ordered a charge that sent his cavalry into yet another carefully planned ambush. The surprised Federals turned and fled for Barnwell and the protection of the Union infantry. Kilpatrick could not make up his mind how to report the incident. ‘[We were] furiously attacked by Wheeler’s entire command,’ he said in one account, ‘and fell back to fight gallantly.’ In a letter to Sherman, however, he claimed the action was’simply a reconnaissance.’

Sherman’s troops entered Columbia on February 17. Before the day ended, the city was ablaze, though it remains unclear who started the fire. As the army paused for a rest, Kilpatrick found himself yet another female companion, a beautiful young woman named Marie Boozer who had been forced to flee her home. ‘She was,’ one admirer remembered, ‘the most beautiful piece of flesh and blood I ever beheld.’ Kilpatrick played the role of savior, abandoning his military responsibilities to ride with Boozer in her elegant carriage. It was in that carriage, with his head nestled in Boozer’s lap, that Kilpatrick entered North Carolina on March 3, 1865.

As Sherman headed for Goldsboro, Kilpatrick rode north of the Union columns, protecting them from enemy assaults. On the evening of March 9, after failing to intercept a Rebel cavalry command led by Wade Hampton, Kilpatrick took refuge in a cabin that lay hidden in a pine forest. He was in bed with Boozer when Hampton paid him a ‘morning call.’

Hearing gunfire outside, Kilpatrick jumped up and opened the door. Rebels were everywhere. In a shocking repeat of his embarrassing flight at Rock Springs, the scantily clad general leaped onto the nearest horse and raced from the scene. His men later recaptured the camp and rescued Boozer.

Kilpatrick rode into Fayetteville on March 11, where he was soon joined by the rest of Sherman’s army. The Yankees rested there for four days, during which time Boozer left Kilpatrick. She sailed down the Cape Fear River to the coast and married a Union officer in Wilmington, using him as her ticket to the North and safety.

On March 19, Major General Henry Slocum’s wing of Sherman’s army, including Kilpatrick’s cavalry, was attacked as it passed Bentonville, North Carolina. As the fight began, Kilpatrick raced up to Slocum. ‘My cavalry is on the field,’ he proclaimed, ‘ready and willing to participate in the battle.’ Slocum scoffed at Kilpatrick’s offer, and sent him to the rear.

Soon, however, there was an outlet for Kilpatrick’s brand of fighting. Johnston, who had been restored to command of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, was retreating to the west, trying to link up with Lee, who had evacuated Richmond on April 1. Sherman’s army took off after Johnston on April 10. ‘You may act boldly and even rashly now,’ Sherman instructed Kilpatrick, who led the Federal advance. ‘This is the time to strike quick and hard.’

Kilpatrick hurried through Raleigh and on to Morrisville, where he was greeted by a Southern cavalryman waving a white flag. Lee had surrendered, the messenger reported, and Johnston felt it was time to lay down his arms too. Kilpatrick sent a courier off to notify Sherman, but when the reply came, Kilpatrick was no longer around to pass it on to Johnston. He had ridden to Durham Station to be with yet another mistress.

The latest object of Kilpatrick’s attention wore an army uniform, and Kilpatrick called her Charley. If the masculine name and garb were meant to be a disguise, the ruse was not working. ‘I know she were a woman,’ a witness related, ‘for I seen her making water. She always let down her pantaloons and squatted.’ Another observer related, ‘General Kilpatrick was very fond of Charley…. He used to lie pretty close to her in bed.’ Poor Molly, meanwhile, heavy with child, was still a laundress, cleaning Kilpatrick’s and Charley’s soiled clothes.

Sherman’s message for Johnston finally found Kilpatrick, who in turn arranged a meeting at the home of James Bennett, halfway between Raleigh and Hillsboro. Sherman and Johnston met on April 17. An agreement was reached, but officials in Washington rejected the pact because it included civil terms over which Sherman had no authority. A second meeting on April 27 resulted in a simple military capitulation.

As a reward for his service with Sherman, Kilpatrick was promoted to major general and given command of troops occupying North Carolina. He soon left his post, however, to go home and campaign for the Republican nomination in New Jersey’s gubernatorial race. Kilpatrick was on to the second step in his life’s plan.

Things went awry fast. Another candidate, Marcus Ward, carried the convention, so Kilpatrick settled for the next best thing: he would work to get Ward elected, in exchange for a Federal government post. In November, Ward won the governor’s seat. Secretary of State William H. Seward kept the Republican Party’s promise and named Kilpatrick ambassador to Chile.

Ever the paramour, Kilpatrick met a young married woman, a Mrs. Williams, during his long voyage to South America. He soon induced her to accompany him to Chile. He remained in Valparaiso, the country’s principal port, for a few days before presenting his credentials. During this period, he was entertained by the Americans living in the city. Williams attended these receptions, where Kilpatrick presented her as his wife.

If Kilpatrick expected to make a clean break with Williams, he was mistaken. On March 12, 1866, he went to Santiago, leaving her in Valparaiso. He expected her to sail quietly for the United States. Instead, she took to the streets as a prostitute. The scandal filtered back to the states in vague terms. One newspaper referred to ‘an American diplomat serving in a South American country.’ Seward cabled the ambassador. ‘It is supposed,’ he said, ‘the one [mentioned] may be yourself. The president deems you should deny the charges.’

Fortunately for Kilpatrick, public interest in his affair ebbed quickly and he was able to keep his job. He proved a surprisingly good ambassador–especially after he met, wooed, and married Louisa Valdivieso, cousin of a future president of Chile and niece of an archbishop of the Catholic Church.

In 1869, Kilpatrick’s affair with Williams returned to haunt him. New President Ulysses S. Grant did not care for such behavior, and he recalled Kilpatrick from his post. When Kilpatrick made another run for the New Jersey governorship that fall, the party convention rejected him for the same reason.

Kilpatrick returned home to Deckertown to begin a career as a lecturer and farmer. He toured the country in the winter, delivering speeches on the Civil War, and the rest of the year tended the fields of his family’s homestead. Nevertheless, Kilpatrick still entertained thoughts of becoming president, and as a stepping stone, in 1880 he ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. He lost, but President James Garfield restored him to his old post in Chile.

Shortly after arriving in Santiago on July 20, 1881, Kilpatrick was struck down by Bright’s disease, a deterioration of the kidneys. In December, just when his strength seemed to be returning, he suffered a relapse and died. He was just 45 years old.

During the Civil War, the egotistical, reckless, and immoral Kilpatrick had proven himself a poor commander. Yet in 1875, the Comte de Paris described him as ‘one of the most brilliant cavalry officers in the late war.’ Kilpatrick built his career on boasts, lies, and imaginary victories. ‘His memory and imagination,’ Major General Oliver Otis Howard once noted, ‘were often in conflict.’

He had been fortunate to wrangle his way into the Union cavalry early in the war. Then, Federal cavalry commanders were so desperate for fighters that they overlooked Kilpatrick’s failings. His willingness to fight put him among a new breed of more capable Yankee cavalrymen such as Farnsworth, Custer, Merritt, and Gregg. But his poor performance made him stand out in ridiculous contrast to these competent officers.

This article was written by Samuel J. Martin and originally published in the February 2000 issue of Civil War Times Magazine.

For more great articles, be sure to subscribe to Civil War Times magazine today!