On a regularly recurring basis the headlines report discovery of a purported image of Wyatt Earp, Billy the Kid, Jesse James or some other historic Western figure, its owner often claiming that facial recognition technology has validated the identity of the subject. But the failure of facial recognition technology to identify, for example, the much-photographed Boston Marathon bombers in April 2013 certainly calls its reliability into question. Identification of historical images requires a higher standard.

Facial recognition technology has become a standby plot device in the plethora of crime scene investigation, or CSI, shows on television. As a former police officer, I seldom watch these shows, as their plots and overreliance on technology bear little resemblance to the real world. In such shows every investigation comes together perfectly, leading to the inexorable solving of a crime. I would love to see just one episode in which valuable evidence went missing because a crime scene tech was too lazy to analyze it—a lapse I witnessed on several occasions.

In a recent CSI show the heroine snapped a cell phone image of a stalker through her apartment window, then transmitted the image to headquarters. A tech there ran the grainy, low-resolution image through a computer, and within minutes facial recognition technology had identified the baddie. The failure of the technology under similar circumstances in Boston makes it clear such a result is grossly improbable. Photographs are two-dimensional images; people are three-dimensional. There are too many variables—angle, resolution, lighting, etc.—for facial recognition technology to provide an exact identification. Anyone who has ever looked at photos of friends and family taken 30 years ago has experienced this; often one cannot identify people they know well. If you cannot recognize your own family members in old photos, why expect a computer to do so?

Facial recognition technology on its own is insufficient to identify historic images

Facial recognition technology became an issue in the summer of 2012 when an otherwise reputable auction house offered an obviously specious image of Wyatt Earp and family at a very high price (more than $100,000). The auction catalog did state clearly that no provenance connected the image with Earp or his family. Yet the auctioneer claimed a forensic expert had “proved” the identity of the main subject.

I immediately contacted the auctioneer, reminding him of the importance of provenance:

There is no provenance at all connecting the image to the Earp family. These so-called look-alikes of the Earp brothers come up regularly on eBay and never sell for more than a few dollars. In fact, there is one on eBay now.…The idea that some ‘expert’…has identified it as the Earps is laughable. As you must know, such a previously unpublished and unidentified image must have provenance connecting it with the Earp family. And no such provenance exists.

The auctioneer responded in part:

[I] am disappointed in your discussion. The forensic expert that made the 21-page report is FBI-trained and is far from ‘laughable.’ He is also very well known to other facial recognition forensic experts. Perhaps you might provide an alternative with a similar background in forensic identification of facial recognition.

I replied as follows:

This photo was the topic of quite a bit of informal discussion and joking at the recent Wild West History Association convention in Arizona. No one, collector or historian, even remotely considered that it was authentic.

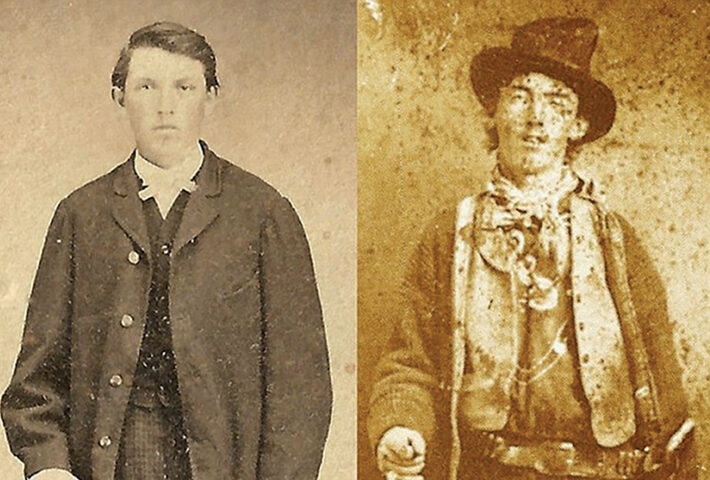

As far as collecting images goes, no serious collector believes in ‘forensic identification’ of facial features. Bill Koch spent all that money on the Billy the Kid image because it has impeccable provenance. Two of the four tins of the Kid survived; one was lost in the ’20s, and the other surfaced in the ’80s, owned by descendants of one of the Kid’s comrades in the Lincoln County War. That is the one Koch bought. Over the past 30 years I have seen dozens of Billy the Kid images; only this one is authentic. All the others, like your ‘Earp’ image, are look-alikes (though many don’t even look like him).

The auctioneer initially rejected my comments. “I am saddened to hear that none in your sphere believe in the science attached to forensic identification,” he wrote. “The photograph was submitted without bias for formal recognition comparative analyses. The results came back positive. Should someone with equivalent credentials…come forward with new evidence, we’d be happy to review it.” Several prominent collectors subsequently contacted the auctioneer, confirming my opinion, and to his credit he withdrew the disputed image from auction.

Unfortunately, such integrity is atypical, and spurious images keep cropping up, such as a recent batch of photos supposedly found in Oklahoma that purport to depict historical lawmen and outlaws, everyone from Sam Bass to Belle Starr to Frank Hamer. They are indisputably old images, but they bear false identifications. The “prize” of the collection is a photo of a young man identified as Billy the Kid reclining on a large rock. The main problem with the image is that it is mounted on a circa 1895–1900 scalloped card and was taken at least 15 years after the Kid’s death. Another questionable photo supposedly depicts the Kid and others playing croquet. While also a vintage image, taken somewhere in the United States circa 1880, it depicts unknown subjects, lacks provenance and is worth about $50, not the $5 million its owner is seeking.

Such look-alike photos are a particular peeve among image collectors. The truth is facial recognition technology on its own is insufficient to identify historic images. WW

California author John Boessenecker, a frequent contributor to Wild West, has written many well-received Western books, including Texas Ranger: The Epic Life of Frank Hamer, the Man Who Killed Bonnie and Clyde (2017).