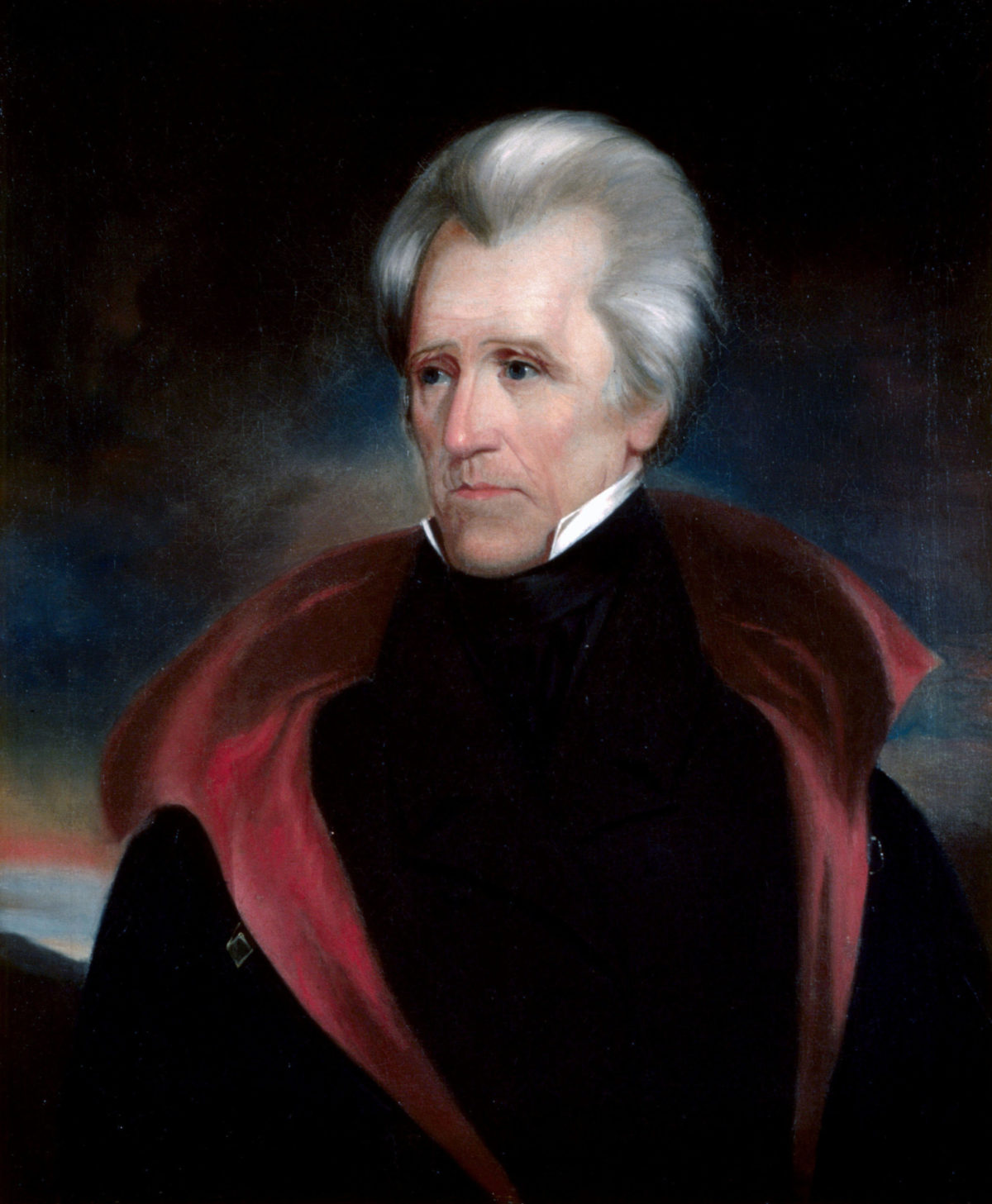

Facts, information and articles about Andrew Jackson, the 7th US President

Andrew Jackson Facts

Born

March 15, 1767

Died

June 8, 1845

Spouse

Rachel Jackson

Accomplishments

7th President of the United States

In Office

March 4, 1829 – March 4, 1837

Vice President

John C. Calhoun (1829-1834)

Martin Van Buren (1834-1837)

Other Notable Facts

Served in American Revolutionary War

Major general in the War of 1812

First Senator from Tennessee

First Governor of Florida

Helped found the Democratic Party, first Democratic President

Only president censured by the Senate

First target of presidential assassination attempt

Paid off national debt while in office

Andrew Jackson summary: Andrew Jackson was the seventh president of the United States. He was a first-generation American, the son of Irish immigrants. He worked hard to advance socially and politically. His actions during the War of 1812—especially his overwhelming victory against British troops at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815—and the Creek War made him a national hero. He is sometimes considered the first modern president, expanding the role from mere executive to active representative of the people, but his Indian removal policies and unwillingness to consider any opinions but his own tarnished his reputation.

Early Life of Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was born near the border of North and South Carolina on March 15, 1767, to Elizabeth Jackson three weeks after the death of his father, Andrew. Two years earlier, the Jacksons had emigrated from northern Ireland with Andrew’s older brothers, Hugh and Robert, to the Waxhaw settlement. Jackson grew up in the settlement, surrounded by a large extended family.

In 1778 the Revolutionary War came to the Carolinas. Jackson and his brothers volunteered to fight the British, but only Andrew would survive the war. (He was barely in his teens when he enlisted and probably served as a courier.) Hugh died of heatstroke following the Battle of Stone Ferry in 1779. In 1781, Jackson and Robert were captured. During that captivity, a British officer struck him with a sword for refusing to polish the officer’s boots, leaving Andrew with a scar on his face and one hand and a hatred for the British; he would carry all three for the rest of his life.

Both Andrew and Robert contracted smallpox. Elizabeth negotiated for their freedom, but Robert would die of the disease on April 27, 1781. After Andrew recovered, Elizabeth went to Charleston to nurse sick and wounded soldiers, where she contracted cholera and died on November 2, 1781—Jackson was just 14. He lived briefly with extended family in Waxhaw, then went to Charleston to finish his schooling. He became known for his daring, his playfulness, and his hot-headed temper.

Law Career

At 17, Jackson decided to become a lawyer after briefly teaching school and moved to Salisbury, North Carolina. He apprenticed with prominent lawyers for three years and in 1787 received his license to practice law in several backcountry counties. To supplement his income as a lawyer, he also worked in general stores in the small towns he lived in.

In December 1787, Jackson’s friend John McNairy was elected by the North Carolina legislature as a judge in the state’s westernmost district, which is now part of Tennessee. McNairy appointed Jackson as a public prosecutor, and he moved west to Nashville in 1788. For the next two years, he practiced law in Nashville and Jonesborough and traveled to several frontier forts.

Marriage and Family

At one frontier fort, he met Rachel Donelson Robards, a woman in a troubled marriage. After hearing that her husband had been granted permission to divorce her, Jackson went to her in Natchez, where her mother had sent her, and may have married her there although there is no record of the marriage. When they returned to Nashville in 1791, they discovered the divorce had not occurred. In 1792, Rachel’s husband sued for divorce on grounds of bigamy—Jackson and Rachel would not officially marry until 1794. Although they did not have children of their own, they took in several children, including two of Rachel’s nephews, naming one Andrew Jackson Jr., in 1808.

Andrew Jackson’s Early Political Career

Throughout the 1790s, Jackson helped lay the foundation for the State of Tennessee, becoming Attorney General district around Nashville in 1791. He served as a delegate to the Tennessee Constitutional Convention and in 1796 traveled to Philadelphia to lobby Congress for statehood. He became Tennessee’s first member of the U.S. House of Representatives, serving from 1796 to 1797, and was selected to be its U.S. Senator, serving 1797–1798.

Due to financial difficulty, Jackson resigned his seat and returned to Nashville, becoming a circuit court judge in 1799 and, at the same time, running a law practice. He also had several business ventures, including general stores and a whiskey distillery at his plantation northeast of the city, which was worked by about 15 slaves. Jackson took many buying trips to stock his stores, traveling to major cities like New Orleans, New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. In 1802, Jackson was elected a major general by the Tennessee militia.

In addition to his business ventures, he formed partnerships that speculated in land sales; he was nearly bankrupted in 1804 after one partnership failed. He sold his plantation and bought a smaller farm nearby that he named The Hermitage. He resigned his position as circuit court judge and opened a general store, tavern, and horseracing course, focusing on his business ventures until the War of 1812. He did maintain connections with public figures, including President Thomas Jefferson and Vice-President Aaron Burr. His friendship with Burr almost cost him his future—Burr was tried for treason in 1807—but Jackson was able to distance himself.

Jackson’s Military Career

When the War of 1812 began in June 1812, Jackson offered his services to President James Madison but was rebuffed for six months due to his reputation for rashness and his association with Aaron Burr. In December, he was finally commissioned a major general and ordered to lead 1,500 troops south to Natchez with the intent to go on to defend New Orleans. In March 1813, the War Department believed the threat to New Orleans had passed and dismissed Jackson and his troops without compensation or the means to return to Tennessee. Outraged, Jackson vowed to get his men home if he had to pay for it himself. During the month-long march home, he earned the respect of his men and the nickname “Old Hickory” for sharing their hardships, marching with his men while allowing the wounded to ride.

In the fall of 1813, Jackson and his troops left Fayetteville, Tennessee, to fight in the Creek War. The war had been incited in part by Shawnee leader Tecumseh who, backed by the British, was trying to defend tribal lands and traditions. Jackson defeated the Creeks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend on March 27, 1814, and ultimately forced the Creeks to sign a treaty in August that ceded about half of their territory to the U.S. Following the Battle of Talladega during the Creek War, a male Indian child was found alive with its dead mother. Jackson adopted the boy, naming him Lyncoya. Initially, Jackson may have intended him simply as a playmate for Andrew Jackson Jr., but as things developed, the general arranged for Lyncoya to be educated along with Andrew Jr. The boy died of tuberculosis in 1828.

When British again threatened the coast along the Gulf of Mexico in the War of 1812, Major General Jackson was given command of the southern frontier. He marched south, first to prevent a British landing at Mobile, and then to New Orleans to defend it against an imminent British invasion. On January 8, 1815, Jackson and his men rebuffed a British frontal assault at Chalmette Plantation outside New Orleans and won the battle, due in no small part to very bad luck on the part of the British. The battle was also unnecessary; a peace agreement had already been signed in Europe, but that news did not reach America before the battle was fought. However, at the Battle of New Orleans, there were about 2,000 British casualties while the Americans had only about 70, and Jackson’s status as a commander and national hero was solidified. This battle marked the last attempt by any foreign nation to invade the United States.

Two years later, when a group of Creek and Seminole Indians refused to recognize U.S. claims to their land and invaded the U.S. from Spanish Florida, attacking settlers as they advanced, Jackson was ordered back into action. In 1817–1818, he pushed the Indians back into Florida and in an unauthorized invasion captured Pensacola. On February 22, 1819, Spain agreed to cede Florida to the U.S. Despite calls to punish Jackson for his unauthorized action, President James Monroe refused to do so, instead offering Jackson the Florida governorship. Jackson became the first governor of Florida on July 17, 1821. His governorship was short-lived and contentious—he resigned December 1, 1821.

The Presidency

Upon his return to Tennessee from Florida, powerful friends nominated Jackson for the U.S. presidency in 1822—although the election would not be for another two years—and elected him the U.S. Senate again. Jackson was able to garner support that would help him go far in the 1824 election, although he lost to John Quincy Adams. Undeterred, Jackson resigned from the Senate in October 1825 and spent the next three years campaigning. In 1828, after a long campaign with mudslinging on both sides, Jackson defeated Adams to become the seventh president. Sadly, his wife Rachel Jackson, who had been deeply affected by the contentious campaign, died December 22, 1828, before he entered the White House.

Jackson’s presidency is often called the first modern presidency because of his belief that the president is not just an executive but a representative of the people, much like a Congressman but for all the people rather than those of a specific district. He entered office determined to end government corruption and the nation’s financial difficulties caused, he thought, by the upper-class elite in government, business, and finance.

Early in his first term, Jackson had to contend with the Eaton Affair. Washington elite and Jackson’s own cabinet members socially ostracized Secretary of War John Eaton and his wife over perceived social differences. Eaton had defended Rachel Jackson during the presidential campaign, and Jackson felt honorbound to reciprocate. At the same time, many of his cabinet members thought he would be a one-term president and were trying to position themselves as candidates in the next election. To solve both problems, in 1831 Jackson dismissed his entire cabinet except for the postmaster general. The controversy caused him to rely heavily on a group of trusted advisors—his opponents called this group Jackson’s “Kitchen Cabinet” because of the unofficial access they had.

Jackson kept a watchful eye on expenditures and appropriations, vetoing bills that he thought did not benefit the country, while his predecessors had vetoed bills only if they deemed them unconstitutional. He monitored the activities of government officers, eventually replacing about 10 percent of them because of corruption, incompetency, or because they opposed him politically—a much higher percentage than his predecessors. He called this the “principle of rotation in office” while other called it the spoils system. (“To the victor go the spoils.”)

In 1832, Jackson vetoed the bill to renew the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, the nation’s central bank. He believed the bank and those who controlled it had too much power and could ruin the country financially for their own gains. In 1833, Jackson dismissed his Treasury Secretary for refusing to remove deposits from the Second Bank and became the only president censured by the Senate for his actions, although the censure was expunged at the end of his second term. Over the next four years, banks bowed to political pressure and relaxed their lending standards, eventually maintaining unsafe reserve ratios. In January 1835, Jackson paid off the entire national debt, the only time in U.S. history that has been accomplished. However, the Panic of 1837 and the ensuing depression, due in part to relaxed lending standards, caused the national debt to begin to increase again.

Andrew Jackson and the Nullification Crisis

Jackson presided over the nation’s first secession crisis. South Carolina declared the right to nullify federal tariff legislation because it hurt the state’s financial interests and threatened to secede in November 1832 following Jackson’s reelection. In December 1832, Jackson introduced a Force Bill to Congress that would allow him to send federal troops to South Carolina to enforce laws and prevent secession. The bill was delayed long enough for a compromise tariff bill that to make its way through Congress. On March 1, 1833, both bills were passed and secession—and civil war—were narrowly avoided. President Abraham Lincoln would later cite Jackson’s actions during the nullification crisis in his attempts to prevent secession and the Civil War.

Jackson’s presidency is also well-known for his policies toward Native Americans, who were being pushed further west during Western Expansion. Jackson believed the backbone of the American economy was small family farms—to maintain strong growth as the population increased, new farmland needed to be opened up. The Indian Removal Act, passed in 1830, was ultimately used to force the removal of Native Americans from the South to the West throughout his presidency, opening fertile land in the South to settlement and causing the Trail of Tears. Spurring Indian removal was the discovery of gold near Dahlonega, Georgia, which led to the Georgia Gold Rush at the end of the 1820s.

Jackson carries the dubious distinctions of being the first president to be physically attacked in office, in May 1833, and the first to have an assassination attempt against him in office (January 1835)—the misfire of both pistols wielded by his assailant only added to his legend.

Jackson’s Later Life

In March 1837 following the inauguration of Martin Van Buren, who had been Jackson’s vice president in his second term, Jackson returned to his plantation, The Hermitage, outside Nashville, now worked by about 150 slaves and run with the help of his adopted son, Andrew Jackson, Jr. Although he retired from public life, he remained politically influential. He used his influence to help Texas enter the Union in 1845 and help his protégé, James K. Polk, win the 1844 presidential election. In 1844–1845, Jackson’s health declined rapidly—he battled constant pains, infections, and illnesses—and he died June 8, 1845, at the age of 78 and was buried in the garden at the Hermitage.

Articles Featuring Andrew Jackson From HistoryNet Magazines

Andrew Jackson: Lawyer, Judge and Legislator

The bear-sized man, on trial for mutilating a child’s ears, stormed about the court, cursing out judge, jury and any man who would try to subdue him. Russell Bean, the “great, hulking fellow,” as one commentator described him, had had enough of lawyers and law books. Bean marched out of the small courthouse into the town square of Jonesborough, Tennessee, wielding a pistol and bowie knife and threatening to kill anyone who dared approach.

A crowd gathered to watch the spectacle. Since, as time passed, no one attempted to apprehend the fugitive, it appeared that Mr. Bean would retain his freedom.

Suddenly, a challenger appeared in the doorway of the courthouse. All eyes focused on the tall, thin man with a pistol clutched in each hand. He advanced deliberately toward Bean. All the bystanders and even the raging giant fell silent. As the pursuer leveled one of his pistols, the onlookers were amazed to see that it was none other than the presiding judge himself. Andrew Jackson of the Tennessee Superior Court had come, determined to preserve justice on the frontier against any threat.

Before the Creek War and the Battle of New Orleans made Jackson a national hero, he earned his living in the legal profession. It may seem strange that someone like Jackson, who famously preferred action to words and would one day defy a Supreme Court decision as president, should turn to the practice of law. But the establishment of justice in the early days of the republic often required a man of Jackson’s skill and demeanor.

In the early 19th century, Tennessee lay on the edge of American civilization. Indian raids, encouraged by both British and Spanish colonial leaders, were still common. The nation’s new capital, Washington, D.C., was more than 600 miles away, with not nearly the influence on local affairs now exercised by the federal government. Life was tough and, as one writer put it, often the settlers would rather have “an ounce of justice than a pound of law.” Jackson fit the bill. He practiced his profession with the same righteous intensity he brought to all of his endeavors.

Jackson first began to take an interest in law following the American Revolution. Several factors in the state of the nation made this an attractive choice. America’s recently earned independence meant a new legal system had to be established specific to the country and to each state. Many pro-British Tory barristers had fled the new nation, leaving a void in the profession for young American lawyers to fill. Additionally, the ceaseless westward movement of new settlers meant there would be a frontier in need of taming. Good lawyers and judges were imperative to civilizing the wilderness. After a church, a courthouse was usually the next public building to appear in any settlement of consequence.

While it is not clear why Jackson consciously chose to practice law, it is clear why he selected a career that would take him away from his birthplace in the Waxhaw District straddling North and South Carolina, where he was born on March 15, 1767. The Revolution had raged through the area, pitting patriot Whig against Tory, neighbor against neighbor and father against son. Following in the footsteps of his older brothers, young Andrew joined the cause of independence at age 13. Jackson was eventually captured and imprisoned. During his captivity, he was wounded by a British officer and he contracted smallpox. His father had died before he was born, and his two brothers and mother perished during the war.

Having suffered through hardship, severe wounding, life-threatening illness and the loss of his immediate family, Jackson never forgot the price he and others had paid to obtain America’s liberties. By 1783, Jackson was a 16-year-old orphan living with members of his mother’s family. His surviving relatives apparently held little affection for the irascible boy, who looked desperately for an escape from their staid existence. To remain in the Waxhaws meant to have a quiet, modest life. Such was not Jackson’s fate.

Although his mother had intended for him to be a clergyman, and his mother’s family taught him the saddling trade, Jackson must have seen opportunities to travel and earn a decent living as an attorney. Before his 18th birthday, Jackson rode to Salisbury, North Carolina, and entered the law office of Mr. Spruce McCay, where he began his legal studies.

A legal education in post-Revolution North Carolina was a far cry from the more formalized education of today’s law schools. It was far removed even from contemporary legal programs in England or in the American Northeast, where John Quincy Adams was commencing his higher education at Harvard College.

This less-formalized Southern education complemented a wilder lifestyle. And Jackson was never far from chicanery. He fell into a crowd of like-minded peers, engaging in cock-fighting, horse-racing, drunken revelry and pranks. On one occasion, after concluding a pleasant dinner at a local tavern, the young men decided that a finer time should not and would never be had with the dining ware they had used. They made good on their feelings by shattering the plates and glasses. Then they broke the table in two, battered the chairs and other furniture into splinters, heaped it all into a pile and set the pile ablaze.

Some of his indiscretions were less destructive but more scandalous. The young Jackson ruffled feathers when, in helping organize a Christmas ball at the town’s dancing school, he invited two notorious prostitutes. The women took the invitation seriously, to the universal embarrassment of all present at their arrival. It was a cruel joke, and Jackson later apologized to the other women at the ball (it is not clear if he ever apologized to the prostitutes). This remains the only documented occasion in which Jackson was less than ideally chivalrous in his dealings with women.

In spite of his youthful distractions, there is reason to believe Jackson was serious in his legal studies. As one of his early biographers, James Parton, claimed in his 1860 Life of Andrew Jackson:

“At no part of Jackson’s career, when we can get a look at him through a pair of trustworthy eyes, do we find him trifling with life. We find him often wrong, but always earnest. He never so much as raised a field of cotton which he did not have done in the best manner known to him. It was not in the nature of this young man to take a great deal of trouble to get a chance to study law, and then entirely to throw away that chance.”

In 1786, Jackson left McCay’s office and moved to that of Colonel John Stokes, where he completed his legal education. On September 26, 1787, judges Samuel Ashe and John F. Williams of the Superior Court of Law and Equity of North Carolina authorized him to practice as an attorney, finding him to be a man of “unblemished moral character” and knowledgeable in the law. At the age of 20, Andrew Jackson was ready to begin his life of public service in the courtrooms of North Carolina.

The next year of Jackson’s life was spent mostly in Martinsville, North Carolina. Legal work was sparse, and Jackson made do working as a constable and assisting in the management of a store with two of his friends. Even with three jobs, his means were limited. During one of his travels to court in the town of Richmond, Jackson stayed at the inn of Jesse Lister, and apparently left without paying his bill. According to tradition, Lister later wrote in his account book that the charge was “Paid at the Battle of New Orleans.” (Jackson as president would deny the validity of this story when presented with the board-bill by Lister’s daughter.)

It was soon clear to Jackson that better opportunities must lie in the West. Although young, and with questionable legal knowledge, Jackson possessed a magnetic character. The friendships he developed in his early years would reap huge benefits throughout his life. They began to pay off in 1788, when Jackson’s fun-loving companion from his law school days, John McNairy, earned an appointment as Superior Court judge for the Western District of North Carolina (in present-day Tennessee). McNairy needed a prosecutor, and Jackson seized upon the offer. Jackson and McNairy, along with several other friends, worked their way from town to town toward Nashville. On the way, Jackson took cases to pass the time between legs of the journey.

At this early stage in his career, Jackson began to earn a reputation for pugnacity. One day in court, Jackson found himself opposed to Colonel Waightstill Avery. Avery was an experienced and respected lawyer, of whom Jackson once had sought legal mentoring. In the course of an address to the court, Avery made a sarcastic quip regarding Jackson’s constant reliance on a journeyman’s lawbook, Matthew Bacon’s Abridgement of the Law.

Jackson, sensing his competence had been questioned, openly accused Avery of taking illegal fees. Avery denied this. Eyes ablaze, Jackson jotted down a message on a page of Bacon’s lawbook, tore it out and placed it before Avery. The older man, wanting to avoid a duel, made no response. A day later, Jackson issued a public challenge. It is telling that this is Jackson’s earliest known letter:

Agust 12th 1788

Sir: When a man’s feelings and character are injured he ought to seek a speedy redress; you recd. a few lines from me yesterday and undoubtedly you understand me. My charector you have injured; and further you have Insulted me in the presence of a court and larg audianc. I therefore call upon you as a gentleman to give me satisfaction for the Same; and I further call upon you to give Me an answer immediately without Equivocation and I hope you can do without dinner untill the business done; for it is consistent with the character of a gentleman when he Injures a man to make a spedy reparation; therefore I hope you will not fail in meeting me this day, from yr obt st.Andw. Jackson

Collo. AveryP.S. This Evening after court adjourned

Unable to avoid an encounter, Colonel Avery agreed to meet Jackson on a hill south of Jonesborough. Fortunately, conciliators prevailed on Jackson, and both men fired into the air. In good humor, Avery presented Jackson with a slab of bacon—a play on the lawbook at the center of the dispute. Jackson didn’t get the joke, and an icy silence prevailed.

The McNairy-Jackson party arrived in Nashville in October 1788. Jackson took up residence in an inn run by the widow Donelson and her children, including her daughter Rachel Donelson Robards. Rachel’s husband James Robards was a jealous and suspicious man. With the dashing young Andrew Jackson in the picture, Robards’ suspicions were inflamed.

Jackson immediately discovered richer law prospects in his new home. The frontier had become a haven for debtors seeking to escape their creditors. Until Jackson’s arrival, the only lawyer in the area had been retained by a combination of these debtors. Jackson championed the creditors, mostly merchants, and he prosecuted the cases boldly and successfully. The business interests of the newly settled land thus became his newest friends and allies.

The young lawyer became a pillar of Davidson County’s legal system. He handled between one-fourth and one-half of all cases during the next seven years. Most of these cases involved land titles, debts, sales and assault. Property and security were the main concerns of settlers, and Jackson’s ability to champion both made him a popular figure in the county.

During his time as a Nashville lawyer, Jackson married Rachel. The events in the love triangle of Jackson, Rachel and Robards over the next three years are fascinating, if somewhat confusing. What is certain is that Rachel and Jackson fell in love with each other, and Robards’ hostile behavior pushed him further and further out of the favor of his wife and her family. By 1791, Robards was in Kentucky, and that summer Jackson married Rachel. Whether the happy couple had misinterpreted some court documents and believed that Rachel and Robards were officially divorced, or whether they simply did not care, is still debated. Robards did not obtain an official divorce until 1793. The scandal of Rachel as a bigamist would plague the couple to the end of their days.

The changing composition of the nation once again improved Jackson’s prospects. The Southwest Territory of the United States had been ceded from North Carolina, and William Blount was appointed territorial governor. Blount, a friend of McNairy and other Jackson associates, was impressed by Jackson’s abilities, and in 1791 he appointed him district attorney of the Mero District (now eastern Tennessee). Blount also conferred upon Jackson his first military appointment, as judge advocate of the Davidson County cavalry regiment.

Jackson continued to prosper professionally and financially, but further events would interrupt his legal career. In 1796, Tennessee achieved statehood, and Blount became one of its senators, while Jackson became its first congressman in the U.S. House of Representatives. A year later, Jackson replaced Blount as U.S. senator from Tennessee. However, his first experience in politics was bittersweet. He missed his wife, despised the lengthy and genteel procedures of legislating, and agonized over a disastrous business transaction. In 1798, he left the Senate and went back to Nashville, not to return to national politics for 25 years.

The ex-senator was not without work for long. A position had opened on the Tennessee Superior Court, and Jackson accepted the election by the legislature.

It is unclear whether Jackson wanted this office, but it was a stepping-stone to the governorship, and it allowed him to remain in Tennessee with his beloved Rachel. The position paid $600 a year and required work in Jonesborough, Knoxville and Nashville.

Rulings were not generally recorded in Tennessee until after Jackson had left the bench, and only five of his written decisions have ever been located. Most sources credit Jackson with having the proper temperament, if not the scholarship, to preside over the state’s courts. According to Parton, “Tradition reports that he maintained the dignity and authority of the bench, while he was on the bench; and that his decisions were short, untechnical, un-learned, sometimes ungrammatical, and generally right.”

“It is doubtful if a more unlearned judge ever sat on a bench,” writes another biographer, “and it would be equally difficult to find one more determined to dispense justice according to his lights.”

The incident with Russell Bean occurred in March 1802, while Jackson was holding court in Jonesborough.

Bean had been the first white man born in what was to become Tennessee. Strong, brave, untamable, he was the embodiment of the frontier. He was also given to alcohol-induced fits of rage. In February 1802, when his wife gave birth to a child he suspected was not his, Bean clipped the infant’s ears. He was arrested, tried and convicted, but he managed to escape into the wilderness.

When Jackson arrived in Jonesborough to hold court, a nearby tavern went ablaze. Acting with typical daring and decisiveness, he led the fight to battle the blaze and possibly saved the town. He received some unexpected assistance from the outlaw Bean.

Bean had rushed into the burning barn, “tore doors from their hinges to release the horses, scaled the roofs of houses, spread wet blankets and,” in the estimation of one witness, “did more than any two men except Judge Jackson.”

Bean was subsequently arrested and brought before Jackson to answer for his crime. It was at this point that he raged against the court officials and marched out of the building.

Jackson was no stranger to the vulgarities of the frontier, but he suffered no slight to his authority. Therefore, according to some sources, with his eyes “ablaze with fury at this assault upon the Majesty of the Law,” he ordered the sheriff to immediately chase down Bean and bring him before the court.

The sheriff left, but soon returned meekly to report he was unable to apprehend the fugitive.

“Summon a posse, then,” Jackson ordered.

The sheriff once again left, but returned to report no man could be found to approach Bean, who had pledged to “shoot the first skunk that comes within ten feet.”

Jackson, so the story goes, angered as much—if not more—by the sheriff’s failure to carry out his orders as by Bean’s contempt, was determined to see his authority upheld.

“Mr. Sheriff,” Jackson said through clenched teeth, “since you cannot obey my orders, summon me; yes sir, summon me.”

“Well, judge, if you say so, though I don’t like to do it; but if you will try, why I suppose I must summon you.”

Jackson adjourned court for 10 minutes and asked for firearms. In the center of the village, Bean was continuing his standoff, while the local citizens looked on, certain they were about to witness a killing. With a pistol in each hand, Jackson waded into the crowd and leveled one of his weapons at the outlaw.

According to the later accounts, he shouted for all to hear, “Surrender, you infernal villain, this very instant, or by God Almighty I’ll blow you through as wide as a gate!”

Those gathered stood in stony silence. For several seconds, it appeared one man or the other would soon be dead from the conflict. Finally, Bean slumped his shoulders and lowered his pistol. The crowd breathed with relief as he was arrested and returned to jail.

When asked later why he gave into Jackson, Bean is reported to have replied, “When he came up, I looked him in the eye, and I saw ‘shoot,’ and there wasn’t ‘shoot’ in nary other eye in the crowd; and so I says to myself, says I, ‘hoss, it’s about time to sing small,’ and so I did.”

Bean would stand trial. Jackson had stood alone and upheld order.

Bean paid a fine, but was pardoned from imprisonment by Tennessee Governor John Sevier in 1803. The infant whom Bean had maimed died in childhood and his wife obtained a divorce, but 10 years later they were reunited, amazingly, with Jackson’s help. Perhaps Jackson had seen some good in the “great, hulking fellow” as they fought that fire in Jonesborough years before. Colonel Isaac Avery, the son of Jackson’s old legal adversary Colonel Waightstill Avery, recalled:

[Bean] was at Knoxville with a boat. His wife, who was still living there, had conducted herself well in the interim….General Jackson was in the town at the time, and interested himself in bringing Bean and his wife together again….He succeeded. They were married again, and, years after, they were living happily together….A true narrative of [Bean’s] life and adventures would show that truth is stranger than fiction.

The reformed Bean would later become the marshal of Memphis, the “Queen of the American Nile.” No doubt his confrontation with Jackson contributed to his decision to keep the peace and join the polite society Jackson had helped establish.

Soon after his showdown with Bean, Jackson became involved in a very public quarrel. In facing John Sevier, Andrew Jackson found himself in confrontation with the most popular man in Tennessee. Considered to be “the handsomest man” in the state, Sevier was “easy, affable, generous, and talkative.” He rose to fame during the Revolutionary War at the Battle of King’s Mountain and fought bravely in 34 other battles.

Sevier won every gubernatorial election between 1796 and 1809 with the exception of 1801, when he could not run due to term limits. He was the leader of the eastern Tennessee political faction that opposed the Blount, or western Tennessee, faction, and therefore was inevitably an adversary of Jackson. Their feud had its beginnings in 1796, when Governor Sevier opposed Jackson’s election as major general of the state militia. Jackson lost that bid. In 1802 ,Sevier himself ran for the position head-to-head against Jackson. This time, Jackson won when his ally, Governor Archibald Roane, broke a tie in the legislature in Jackson’s favor.

At one point during the drawn-out quarrel, as Jackson was traveling from Nashville to Jonesborough, a friend warned him that a mob of Sevier supporters was preparing to strike. Jackson was ill at the time, but nevertheless continued into town. He procured a room and took to bed.

Before long, a messenger came to tell Jackson that a Colonel Harrison and a group of men had gathered, intending to tar and feather him. Reportedly, Jackson immediately rose from his bed and shouted to be heard, “Give my compliments to Colonel Harrison, and tell him my door is open to receive him and his regiment whenever they choose to wait upon me, and that I hope the colonel’s chivalry will induce him to lead his men, not follow them.”

The would-be attackers dispersed in the face of such defiance. Jackson was able to hold court and leave town without further conflict.

When Sevier challenged Jackson’s friend, the incumbent Governor Roane in the 1803 election, the feud eventually boiled over into an absurd, half-baked duel outside of Knoxville.

Jackson had come into possession of evidence incriminating Sevier in a fraudulent land warrant scandal. In July, he and Governor Roane made this information public. The revelations hurt Sevier’s reputation in the state and enraged him against Jackson.

That October, Jackson was holding court in Knoxville. The legislature had convened in the city, preparing to discuss the scandal. While accounts of what happened during the next few days vary, it seems that Sevier stood on the courthouse steps, defending himself and denouncing his enemies to the multitude gathered. As Jackson exited the courthouse, Sevier immediately began ranting against the judge, unleashing upon him what someone called a “volley of vituperation.”

Jackson, taken aback by this unexpected encounter, began to list the services he had provided to the state.

“Services?” Sevier mocked. “I know of no great service you have rendered the country, except taking a trip to Natchez with another man’s wife.”

This reference to his elopement with Rachel startled Jackson.

“Great God!” he shot back. “Do you mention her sacred name?”

Sevier drew his pistol while Jackson charged at him with his cane. The crowd separated the two men before anyone was hurt.

In the following days, both men challenged the other to render satisfaction. They finally agreed to meet in Indian Territory on October 10. When the two met, Jackson was seconded by Dr. Thomas J. Van Dyke, and Sevier was accompanied by Andrew Greer and George Washington Sevier, his son.

Both enemies dismounted, drew pistols and commenced to verbally assault one another. After a few minutes, they calmed down and holstered their pistols, but continued to exchange insults. Finally, Jackson ran at Sevier, intending to cane him. Sevier drew his sword, but scared his horse, which galloped off with his pistols. Jackson quickly drew one of his own pistols.

Terrified, Sevier ran behind a tree, and damned Jackson for trying to shoot an unarmed man. George Washington Sevier drew his pistol on Jackson, and Dr. Van Dyke drew his pistol on George. It was up to Greer to calm the adversaries and coax Sevier out from behind the tree.

The five men rode to Knoxville, with Jackson and Sevier continuing to launch their verbal salvos at one another. After several days of additional public accusations and challenges, both men ceased and moved on with their lives.

Sevier would serve as governor for six more years before being elected to the state Senate and then the U.S. Congress, dying in 1815. By then, Jackson had also moved on to bigger things. It is fortunate for both Tennessee and the nation that only their egos were injured during the bitter quarrel.

In May 1803, a few months before the Knoxville duel, the Thomas Jefferson administration had completed the Louisiana Purchase and Jackson lobbied for an appointment as governor of the new territory. The position, however, went to another. This disappointment, combined with further financial troubles, convinced Jackson to withdraw from civil service for a time.

On July 24, 1804, the Tennessee legislature accepted Jackson’s resignation. This ended his career in the legal profession. He would continue in his role of major general of the militia, but the next few years would feature a number of setbacks. He would develop a reputation as a violent and rash man after his quarrel with Sevier and a notorious duel with Charles Dickinson over a horse-racing wager. His disastrous friendship with Aaron Burr would almost permanently destroy his reputation when Burr was charged with treason. By the War of 1812, Jackson would be a man in desperate need of a worthy cause.

Although Jackson would be better known as a military hero and political leader, it was his law practice that gave him the opportunities to enter those other fields, and Jackson’s service as district attorney, congressman and judge earned him popular support and valuable allies throughout Tennessee. These strengths sustained him during the darker times. By the end of his judgeship, a new county in Tennessee was named Jackson. By the time of the Civil War, the name Jackson would appear on a map of the United States more than any other besides that of Washington.

Even before New Orleans made him a national hero, Jackson was known as an extraordinary man. He was no legal scholar, but the early 19th-century American frontier was a different place, and Jackson was a different kind of man and a different kind of judge. Soon, the world would see what type of leader the American frontier was capable of producing.

This article was written by Christopher G. Marquis and originally published in the April 2006 issue of American History Magazine.

For more great articles, subscribe to American History magazine today!

Andrew Jackson: The Petticoat Affair—Scandal in Jackson’s White House

President Andrew Jackson was irate, convinced that he was the victim of “one of the most base and wicked conspiracies.” For him, the scandal known as “the petticoat affair” was a social matter that his enemies had exploited and blown out of proportion. It was true that the situation had taken on a life of its own. “It is odd enough,” Senator Daniel Webster wrote to a friend in January 1830, “that the consequence of this dispute in the social . . . world, is producing great political effects, and may very probably determine who shall be successor to the present chief magistrate.”

Always eloquent, in this case Webster also proved prophetic. For the imbroglio to which he referred—involving the young wife of the secretary of war, a woman much favored by Jackson but snubbed by Washington’s gentility for her outspokenness and allegedly sordid past—did ultimately help decide the fortunes of two powerful rivals eager to follow “Old Hickory” into the White House. The cause of the turmoil was the young and vivacious Margaret “Peggy” Eaton, although she was still Margaret Timberlake when Jackson initially made her acquaintance. She was the daughter of William O’Neale, an Irish immigrant and owner of a commodious Washington, D.C., boardinghouse and tavern, the Franklin House on I Street. The tavern was especially popular with congressmen, senators, and politicians from all over the growing United States. Margaret, the name she apparently preferred over “Peggy,” was born at those lodgings in 1799, the oldest of six O’Neale children. She grew up amidst post-prandial political clashes and discussions of history, international battles, and arcane legislative tactics. Margaret observed the nation’s lawmakers at their best and at their worst, and the experience taught her that politicians were as flawed and fallible as anybody else. Far from home and family, these gents were easily charmed by the precocious and beautiful girl and did their best to spoil her rotten. “I was always a pet,” she later remarked.

It was a curious upbringing for a girl in those days, when women were expected to be submissive and demure, domestic and irreproachably virtuous, and utterly uninterested in politics, much less able to argue governmental issues with anything approaching insight. Margaret’s parents could only try to balance her exposure to the often coarse world of men by sending her to one of the best schools in the capital, where she learned everything from English and French grammar to needlework and music. When she showed a talent for dance, Margaret took private lessons, becoming skilled enough by the age of 12 to perform for First Lady Dolley Madison. Moreover, many a guest at the Franklin House remarked on Margaret’s piano-playing prowess. Jackson once wrote to his wife, Rachel, at home in Nashville, Tennessee, that “every Sunday evening [she] entertains her pious mother with sacred music to which we are invited.”

Jackson met Margaret in December 1823, when he traveled to Washington as the new junior senator from Tennessee and boarded at the Franklin House. Like so many others in federal service, Jackson had had no intention of relocating to the capital. At that time it was a scattered, muddy, and manifestly Southern town that had recovered from the British invasion of 1814 but remained short of municipal conveniences. Furthermore, the wickedly humid weather in the spring and summer prompted lawmakers to complete their sessions by early April, then escape to cooler climes.

The Franklin had been recommended to Jackson by John Henry Eaton, Tennessee’s senior senator and the author of a biography that affirmed Jackson’s heroism as the general who vanquished the British army at New Orleans in 1815. Jackson had taken a liking to hotelier O’Neale and his “agreeable and worthy family.” He was especially fond of Margaret, the 23-year-old wife of navy purser John Bowie Timberlake, with whom she bore three children (one of them dying in infancy). She was, Jackson said, “the smartest little woman in America.” Rachel Jackson was equally impressed by Margaret when she accompanied her husband to Washington in 1824.

It was Old Hickory’s friend Senator Eaton, however, who appeared most thoroughly bewitched by the dark-headed, blue-eyed, and fine-featured tavern-keeper’s daughter. A handsome and wealthy widower nine years older than Margaret, Eaton had known her ever since he began staying at the Franklin House as a newly appointed senator in 1818. That was long enough for him to have heard all the rumors about Margaret’s premarital teenage romances. The gossip included tales of how one suitor swallowed poison after she refused to reciprocate his affections; how she had briefly been linked with the son of President Jefferson’s treasury secretary; and how her elopement with a young aide to General Winfield Scott had gone seriously awry when she had kicked over a flowerpot during her climb from a bedroom window, awakening her father, who dragged her back inside.

Such stories—coupled with the fact that Margaret Timberlake tended toward flirtatiousness, enjoyed serving men in her family’s tavern, and shared her opinions and jokes too loudly and liberally—led others in the capital to presume that she was a wanton woman. Eaton, though, saw her quite differently. He had become a confidant of John Timberlake and even fought, though unsuccessfully, to have his Senate colleagues reimburse the often financially troubled purser for losses Timberlake sustained while at sea. Moreover, when Timberlake was away, Eaton was glad to escort his wife on drives and to parties, enjoying both her humor and intelligence.

Margaret called Eaton “my husband’s friend . . . he was a pure, honest, and faithful gentleman.” Rumormongers, however, credited the relationship between the Timberlakes and Eaton with far less innocence. They slandered John Timberlake as a drunk and ne’er-do-well and claimed that the real reason he kept sailing away from home was because he couldn’t face either his financial woes or his wife’s patent philanderings.

This talk grew uglier when, in April 1828, Timberlake died of “pulmonary disease” while serving in Europe aboard the USS Constitution. Amidst the widow’s grieving, rumors spread that the purser had not perished naturally at all but had committed suicide in despair over his wife’s behavior. The situation caused distress not only to Margaret and Eaton, but also to Jackson, whose recent memories of defending his own wife against malicious murmurs made him all the more sympathetic to Margaret’s plight.

Jackson’s first campaign for the White House in 1824 ended with his winning the bulk of the national popular vote but losing the presidency when his failure to gain a majority in the Electoral College threw the race to the House of Representatives, which preferred John Quincy Adams. It was a particularly dirty contest, as Adams’ backers strove to undercut Jackson’s appeal in any way possible. Their tactics included ridiculing his lack of education and accusing him of everything from blasphemy to land frauds and murder. They even resurrected allegations that Rachel Jackson had been a bigamist and adulteress.

Those last charges stemmed from Rachel’s first marriage to a rabidly jealous Kentucky businessman named Lewis Robards. The pair had wed in 1785, but Robards believed that his wife was unfaithful and sought a divorce in 1790. A year later, assuming that she was once more a free woman, Rachel married Andrew Jackson, an ambitious, red-headed young attorney whom she’d met when he boarded at her mother’s home in Nashville. Not until 1793 did the Jacksons learn that Robards had only just been granted a divorce and that they’d been living very publicly in sin for more than two years.

To quash further scandal, the Jacksons promptly retook their vows. Yet claims of Rachel’s immorality haunted the couple. Early in the 1828 presidential race, rumors arose again in pro-Adams newspapers, one of which asked in an editorial, “Ought a convicted adulteress and her paramour husband to be placed in the highest offices of this free and Christian land?” Jackson went on to win that election, becoming the first president from the emerging West and creating what is today the Democratic Party. Yet when Rachel died of a heart attack less than three months before his inauguration, Jackson blamed the political defamers for hastening her demise. “May God forgive her murderers,” the president-elect said at his wife’s funeral, “as I know she forgave them. I never can.”

Even if Rachel had survived, Jackson would likely have supported Margaret Timberlake against character assaults; he had a long record of precipitant gallantry. Following Rachel’s death, however, Jackson became still more stubborn in championing the hotelier’s daughter, equating her with his late mate as a woman unjustly scorned. When John Eaton told Jackson of his wish to do what was “right & proper” by marrying Mrs. Timberlake, the president counseled swift action. Damn the gossipers, he insisted, “if you love Margaret Timberlake go and marry her at once and shut their mouths.”

Unfortunately, the candle-lit nuptials held at the O’Neale residence on January 1, 1829, only incited fresh criticism of the couple. Louis McLane, an eminent Maryland politician (who would hold the positions of secretary of the treasury and state in Jackson’s second cabinet), sniped that the 39-year-old Eaton had “just married his mistress—and the mistress of 11-doz. others!” Margaret Bayard Smith, a Washington society maven whose husband was president of the local branch of the Bank of the United States, proclaimed Eaton’s reputation “totally destroyed” by this union with a woman who hadn’t even waited a respectful period of time before marrying again.

Floride Calhoun, wife of John C. Calhoun—the South Carolinian who had served John Quincy Adams as vice president and would hold the same office under Jackson—accepted a social call from the Eatons after their wedding. Nevertheless, she steadfastly refused to pay a return visit, which in the protocol-bound world of Washington could only be interpreted as a calculated snub. This left John Calhoun to ponder “the difficulties in which [such a rebuffing] would probably involve me.”

Worried that fallout from this fracas might wound the president-elect, some of Jackson’s partisans tried to dissuade him from naming Eaton to his cabinet. It was the wrong approach. Jackson had said many times, “when I mature my course I am immovable.” Since Rachel’s death, he had found greater need of his friend Eaton’s advice, and he wasn’t apt to abandon the man simply because of attacks by “malcontents” on Margaret’s propriety. Jackson reportedly thundered at one Eaton detractor: “Do you suppose that I have been sent here by the people to consult the ladies of Washington as to the proper persons to compose my cabinet?” Jackson soon announced the appointment of Eaton as his secretary of war.

Hopes that this prestigious position might help to rehabilitate Margaret’s reputation were dashed as early as Jackson’s inauguration in March 1829, when the spouses of other cabinet members and politicos obviously slighted the seventh president’s “little friend Peg.”

According to modern Jackson biographer Robert V. Remini, at a grand ball on inauguration night, “the other ladies in the official family tried not to notice as Peggy Eaton swept into the room and startled everyone with her presence and beauty.” Even Emily Donelson, Jackson’s beloved niece and his choice as the new mistress of the White House, turned a chilly shoulder to Margaret. She claimed that Eaton’s elevation to the cabinet had given his wife airs that made her “society too disagreeable to be endured.”

During his early months in office, Jackson had intended to concentrate on replacing corrupt bureaucrats. Instead he was plagued by what Secretary of State Martin Van Buren dubbed the “Eaton Malaria.” Jackson decided to delay his formal post-inaugural cabinet dinner, fearing bad blood between Mrs. Eaton and the rest of the political wives. The president was continually distracted from the nation’s business by having to defend Margaret—despite her protestations that she did “not want endorsements [of virtue] any more than any other lady in the land.”

On the evening of September 10, 1829, Jackson concluded that if this flap was to end, he must take decisive action. With Vice President Calhoun at home in South Carolina and John Eaton not invited, the president summoned the balance of his cabinet, plus Reverends John N. Campbell and Ezra Stiles Ely, who had recently criticized Margaret’s morals. Though ailing from dropsy, chest pains, and recurring headaches, the 62-year-old president proceeded to proffer evidence—affidavits from people who had known Mrs. Eaton—that he said absolved her of misconduct. When one minister dared to disagree, Jackson somehow forgot that Margaret was the mother of two surviving children from her marriage to John Timberlake as he shot back: “She is as chaste as a virgin!”

Thinking the matter was settled, Jackson finally held his overdue cabinet dinner in November 1829. While it provoked “no very marked exhibitions of bad feeling in any quarter,” recalled Van Buren, the event was nonetheless awkward and tense. Guests rushed through their meals in order to avoid discussion of or with the Eatons, who had found places of honor near Jackson. The next party, hosted by Van Buren (who had neither daughters nor a living spouse to inhibit his societal intercourse), drew every member of the cabinet—but their wives contrived excuses for staying away.

By the spring of 1830, Jackson had come to believe that the situation did not result merely from connivances among the gentry, but from scheming by his political foes. Initially he imagined the plot was led by his renowned Kentucky rival Henry Clay, who would doubtless benefit from his administration’s “troubles, vexations and difficulties.” As the president watched his cabinet split over this petticoat affair, however, he couldn’t help noticing that those advisors most opposed to the Eatons were also the strongest followers of John Calhoun—a man he was coming to distrust.

Tall, wiry, and earnest, Calhoun had helped elect Jackson to the White House, and many assumed that he’d be Old Hickory’s successor. Nevertheless, the vice president eschewed the capital during most of the Jackson administration’s tumultuous first year, and what the president remembered from Calhoun’s brief time there—notably, his wife Floride’s refusal to reciprocate Margaret Eaton’s social call—rubbed him the wrong way. One historian, J.H. Eckenrode, argued a century later that it was Calhoun’s “vain and silly wife” who, by spurning Margaret, ruined her husband’s career “at its zenith.” Certainly Floride Calhoun’s obstinacy, when combined with policy differences between her husband and Jackson—especially on the question of whether states should be allowed to nullify federal laws—drove a deep wedge between the nation’s two highest-ranking officials.

At the same time that Calhoun was falling from grace with the president, Secretary of State Martin Van Buren’s fortunes were rising. The former governor of New York, charming in person and a skilled behind-the-scenes strategist (allies and enemies alike called him “the Little Magician”), Van Buren had won the president’s regard by showing respect for John and Margaret Eaton. He became Jackson’s dear friend, someone the president felt was well qualified to one day fill his shoes. Calhoun’s backers realized that Jackson’s dwindling faith in the vice president played to Van Buren’s advantage. Daniel Webster wrote that since Jackson had become so dependent on his secretary of state, “the Vice President has great difficulty to separate his opposition to Van Buren from opposition to the President.” Calhoun could only pray that his public approval or a Van Buren slip-up would still propel him into the presidency.

For two years the press and pundits savaged the administration over Jackson’s support for the Eatons. The nastiest rumors about the couple spread with impunity. One even averred that the war secretary had fathered a child with a “colored female servant.” Van Buren saw as well as anybody how Margaret Eaton had become a liability for the Democrats and a personal burden to Jackson. The president had even sent his nephew and private secretary, Andrew Jackson Donelson, and his wife, Emily, back to Tennessee when they refused to associate with the Eatons. Andrew Donelson expressed his sadness in parting from his uncle, “to whom I have stood from my infancy in the relation of son to father.” Harmony needed to be restored within the administration. Yet if the president discharged the anti-Eaton minority from his cabinet, he risked alienating Calhoun’s contingent of the party, and if he dumped his secretary of war after all this time, he would seem to have caved in to his critics.

The solution was presented to Jackson in April 1831 by Van Buren, when he offered to resign and suggested that John Eaton do likewise. This would permit the president to ask the remainder of the cabinet to do the same and allow for a reorganization. Though a few members resisted, later protesting their departures in print, they all relinquished their seats.

The capital reeled at this turn of events, and some people predicted that it portended governmental collapse. Newspapers were quick to trace the cause of the cabinet’s fall to Margaret Eaton. One publication likened the event to “the reign of Louis XV when Ministers were appointed and dismissed at a woman’s nod, and the interests of the nation were tied to her apron string.” Henry Clay figured Calhoun could now “take bolder and firmer ground against the president,” dooming Jackson’s chances of reelection in 1832 and maybe improving Clay’s own chances of winning the White House. Others hoped that John Eaton’s resignation would finally end talk of his blackballed wife, giving rise to that season’s most popular toast: “To the next cabinet—may they all be bachelors—or leave their wives at home.”

Elected to a second term, Jackson was eager to end the debate that had threatened to bring down his first administration. He hustled John Eaton and his wife off to the Florida Territory, where John became governor. Two years later Jackson appointed Eaton as the United States’ minister to Spain, and Margaret and John enjoyed life in Madrid for four years.

Bitter over the decline of his political fortunes, Vice President Calhoun sought revenge against Martin Van Buren. In 1832, Calhoun cast the tie-breaking vote against the New Yorker’s confirmation as U.S. minister to Great Britain. This rejection, Calhoun told a colleague, “will kill him, sir, kill him dead.” On the contrary, it won Van Buren sympathy with the American public. In 1832, Van Buren became Jackson’s running mate for the upcoming presidential election, and in 1836, he was voted into the White House himself. Calhoun, meanwhile, resigned the vice presidency in 1832 to return to the Senate.

Amazingly, despite their history, Eaton eventually turned on Jackson. In 1840, when President Van Buren recalled Eaton from Spain for failing to fulfill his diplomatic duties, Eaton announced his support for Van Buren’s presidential rival, William Henry Harrison. Jackson was infuriated by Eaton’s political disloyalty, claiming that “He comes out against all the political principles he ever professed and against those on which he was supported and elected senator.” The two men didn’t reconcile until a year before Jackson’s death in 1845.

John Eaton died in 1856, leaving a small fortune to his wife. Margaret lived in Washington and, after her two daughters married into high society, finally received some of the respect she craved. She didn’t enjoy it for long. At age 59, the once-vivacious and now wealthy tavern-keeper’s daughter married her granddaughter Emily’s 19-year-old dance tutor, Antonio Buchignani. Five years later, Buchignani ran off to Italy with both Emily and his wife’s money.

Margaret died in poverty in 1879 at Lochiel House, a home for destitute women. She was buried in the capital’s Oak Hill Cemetery next to John Eaton. A newspaper commenting on her death and on the irony of the situation editorialized: “Doubtless among the dead populating the terraces [of the cemetery] are some of her assailants [from the cabinet days] and cordially as they may have hated her, they are now her neighbors.”

This article was written by J. Kingston Pierce and originally appeared in the June 1999 issue of American History magazine. For more great articles, subscribe to American History magazine today!