When the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, america lacked a practical scout plane to span the gap between primary trainers such as the Curtiss JN-4 and Sopwiths, Spads and other frontline fighters. That deficiency and the desire for a practical American-made fighter served as the primary motivation for the development and fast-tracked production of the Thomas-Morse Scout. The “Tommy,” as it was nicknamed, became the first modern American fighter, despite the fact it was designed by an Englishman, Benjamin Douglas Thomas of JN-4 “Jenny” fame (see Genesis of the Jenny).

William T. Thomas and his brother Oliver W. Thomas (no relation to B.D.) were British subjects born in Argentina. William worked for Curtiss as an engineer from 1908 to 1909, then left to set up his own shop in 1910 with his brother in a barn in Hammondsport, N.Y. The Thomas Brothers Company recruited Curtiss employee Walter Johnson, another self-starter who had taught himself to fly, to serve as a mechanic, test pilot and flight instructor.

In 1912 the company produced the Thomas TA biplane, which was somewhat successful as an exhibition flier and even won a few races. That year the brothers also established the affiliated Thomas School of Aviation at Conesus Lake in New York, famed for its rock-bottom prices (on rainy days student pilots could work off tuition in the shop). In 1913 they changed the name to Thomas Brothers Aeroplane Company, and in 1914 moved to Ithaca, N.Y. B.D. Thomas had parted company with Glenn Curtiss by then, and decided to join them. Once on board, B.D. designed a series of T-2 tractor biplanes for Britain’s Royal Naval Air Service, which were fitted with floats and sold to the U.S. Navy as the SH-4.

In January 1917 the company recapitalized by merging with the Morse Chain Co., thus becoming the Thomas-Morse Aircraft Co., still based in Ithaca. With war tearing Europe apart and the increasing possibility of U.S. involvement, Thomas-Morse sought to design an intermediate trainer/scout that would make the transition to high-performance fighters smoother for the American pilots, thus resulting in fewer casualties due to training accidents. The result was the successful S-4 Scout biplane trainer.

The elegant though outdated French Nieuport 28 influenced the S-4’s design. Both featured long tail moments and Gnome engines, and the S-4B would borrow the torque-tube and bellcrank ailerons featured on the Nieuport 11 through 27 and on Germany’s Halberstadts. The S-4 also borrowed from Sopwith aircraft—especially the wings, which were similar in construction and shape to Camel and Pup wings, although the Tommy had ailerons only on the upper wing to slow down the roll rate for fledgling pilots.

The S-4 Scout was a trim little single-seat biplane that was originally powered by a 100-hp Gnome monosoupape 9B rotary engine. In June 1917, on its first flight, the Tommy attained a speed of 95 mph. After building 52 Tommies, however, Thomas-Morse substituted the more reliable 80-hp Le Rhône 9C.

The initial Army order was for six prototypes. On October 3, 1917, 100 improved S-4Bs were ordered, plus an additional 25 aircraft for Britain.

The Tommy could be easily converted into a seaplane, given the U.S. Navy designation S-5. It was identical to the S-4B save for its floats, which reduced the top speed to 90 mph. After testing at the naval air station on Dinner Key, off Miami, Fla., the Navy ordered six S-5s.

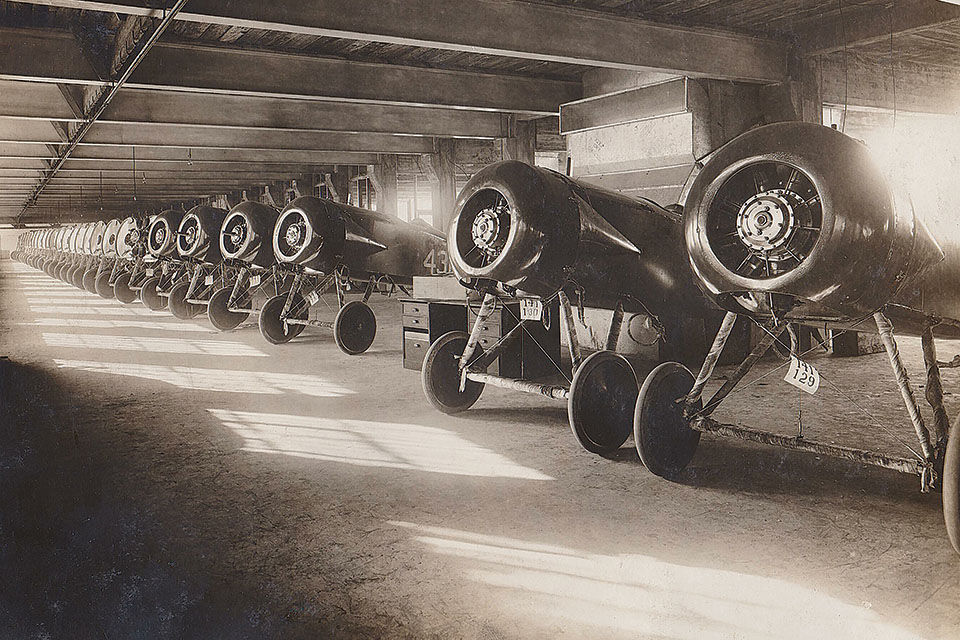

On January 18, 1918, the War Department placed an order for 400 improved S-4C models. Besides using the Nieuport’s torque-tube system instead of cables for aileron control, the C model’s ailerons and elevators were reduced in area and provision was made for a .30-caliber Marlin machine gun, synchronized to fire through the propeller (though not all aircraft were delivered so equipped). A total of 447 S-4Cs were built.

The S-4C was of standard construction with a wire-braced, wooden-frame fuselage, covered in fabric and with a round upper decking. Its wooden interplane struts were braced by wire, with the center section struts slightly splayed outward. The wings were staggered, with a semicircular cutout in the trailing edge of the upper wing to improve visibility. The top wing was flat and the lower wing had slight dihedral (similar to Camels and Nieuports). Wooden struts formed the undercarriage legs, and the wheels were sprung with rubber bungee cords. The engine was partially enclosed by a circular cowling, which was faired into the flat-sided fuselage by triangular cheek cowls similar to those on the Fokker Dr.I triplane.

The Tommy’s controls proved problematic in flight, and the airplane was very tail heavy. The pilot had to constantly push forward on the control stick to keep the aircraft level, as there was no provision for trim control. The roll rate was sluggish, and the torque of the rotary engine made it difficult to loop. Takeoffs were tricky until enough speed built up to allow rudder control. In order to land, the pilot had to “blip” the engine (cut ignition) to reduce power.

According to the late Frank Tallman, who flew the Tommy as a stunt pilot in the 1960s and ’70s, “An incipient ground loop was part of the Scout’s characteristics, primarily because of the landing gear’s location almost under the engine.” Tallman noted that the Tommy had a roomy cockpit—“big enough to swing a cat in”—and that visibility was better than in a Camel. He said the ailerons felt heavy on takeoff and that while flying, you “Had the feeling that the plane was going to leave you control-less…[you] never feel secure.” Tallman allowed that he “Never felt like rolling or looping the Tommy, and I didn’t care who knew it.”

After World War I, the Army Air Service sold surplus Tommies to civilian flying schools, sportsman pilots and ex-military fliers. Some were still being used in the mid-1930s for Hollywood WWI aviation films. A Tommy even shows up in the final dogfight segment of the 1975 movie The Great Waldo Pepper, in which Axel Olsen was charged with setting the plane on fire and simulating a jump to his death. Roger Freeman—president, pilot and vintage aircraft builder/restorer of the Old Kingsbury Aerodrome in Texas—worked with Tallman on the set of Waldo Pepper when he was just 18. Freeman is fond of Tommies and currently flies two of them at Old Kingsbury. He said he likes the airplanes because of what they represent, not how they fly. His dad, Ernie Freeman, had a Tommy in pieces in their garage that they restored together when Roger was younger, so his ties to the aircraft run deep.

Freeman cautioned that as long as the Tommy is kept within its parameters it flies fine. He noted that the little airplane will get off the ground well before you think it should, and that the pronounced engine torque is challenging. The knife-like steel portion of the tailskid is extremely important to keep the airplane straight during takeoffs and landings—without it ground loops are frequent. Freeman confines his aerobatics in the Tommy to steep wingovers.

In New York, there is an S-4B at Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome and at the Ithaca Aviation Heritage Foundation, where they have restored a locally built 1918 example. The IAHF said their Tommy “embodies the spirit of technological innovation that always has run deep in the culture of Ithaca and Tompkins County.” The Tompkins Center for History and Culture will be the IAHF Tommy’s permanent home. On September 29, the IAHF’s Tommy took to the air in a public flight demonstration to celebrate the airplane’s 100th birthday.

Mark C. Wilkins is a historian, writer and museum professional who specializes in World War I aviation. He is a writer and aerial effects producer for a Lafayette Escadrille documentary film currently in production (see thelafayetteescadrille.org).

This feature originally appeared in the November 2018 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!