In the mid-1990s, Jay Leno, commenting on the quick cancellation of Chevy Chase’s much ballyhooed talk show, offered words of solace to the comedian: By lasting five weeks, Chase at least had survived as a late night host longer than William Henry Harrison had as president. Such is the modern legacy of the ninth president of the United States—a punch line. In America’s collective historical awareness, the Harrison presidency is usually reduced to a one-sentence summary: An aged war hero stood without hat or coat in inclement weather, made a lengthy inaugural address, caught pneumonia and died a month after taking office. On the surface, at least, this simplified version of events seems adequate. Harrison didn’t have time to make an important contribution to the office. There were no court appointments, no acts of legislation and no political agenda to be carried on by a successor. The Supreme Court ruling on the case of the mutiny aboard the slave ship A mistad—an action requiring no executive involvement—is the sole event during his stint in office that merits mention in modern history books. Otherwise, the 31 days William Henry Harrison occupied the White House remain the forgotten days of a forgotten president.

Reconstructing the events of those days is difficult. Surviving newspapers of the era are more opinionative than reportorial. The last thorough Harrison biography was written three-quarters of a century ago. Yet accounts of the man’s activities during his term do appear in the memoirs of contemporaries and in piles of documents researched by scholars. There are vignettes of Harrison buying a cow, greeting a delegation of Indians and escorting ladies to their carriages after Sunday services. While it is difficult to paint a detailed portrait of history’s shortest presidency, a rough sketch of his last days is possible.

Harrison’s Election and Inauguration

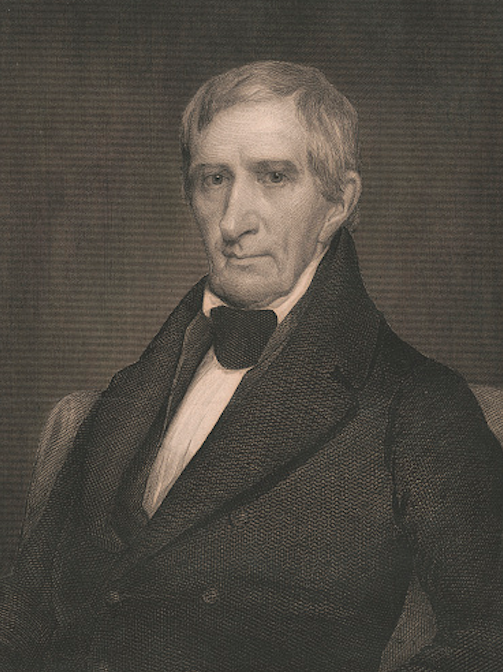

The first morning of Harrison’s term in office began March 4, 1841, with the president-elect mounting a majestic white stallion to ride the length of his inaugural parade route. Organizers had arranged for a comfortable carriage to transport the 68-year-old ex-soldier, but he would have none of it. A crowd estimated at 50,000—the largest to attend an inauguration since George Washington’s—had traveled to the capital to see the man they called “Old Tippecanoe” assume the reins of leadership amid military-like pageantry. Harrison, who loved nothing more than basking in the warmth of applause, would not deny them their wish. Riding his horse slowly, bowing with hat in hand, he took care to graciously acknowledge the cheers. The two-hour-long parade featured music, military drills and horse drawn floats. It was the elaborate final leg of a meandering multistate victory celebration that had started 38 days earlier in North Bend, Ohio.

That this affable man of average talents would make such a trip was scarcely imagined five years earlier. During his second term, incumbent Democrat President Andrew Jackson signaled he would not seek a third term and some Democrats began casting about for a fresh war-hero-as-statesman candidate to replace him. They found Richard Johnson, who, like Jackson, had gained fame in the War of 1812.

Colonel Johnson claimed that he had led the successful attack against the British and their Indian allies during the 1813 Battle of the Thames. The Whigs, a new political party organized to oppose the Democrats in the upcoming election, sought out Johnson’s old commander, retired Maj. Gen. William Henry Harrison, 63 years old and living in Ohio. Initially, Harrison’s assertion that he, not Johnson, had been fully in command at Thames was publicized merely to discredit the Democrat. The unexpected result, however, was that it created an excitement among the Whigs for a war-hero candidate of their own.

Harrison was 25 years past his first glory days, when, as the governor of Indiana Territory, he had led a militia force to squelch an Indian uprising at Tippecanoe Creek in 1811. This earned him celebrity and a nickname. He’d spent the years since that battle and his successes in the War of 1812 cashing in his fame on a succession of political offices. But he’d proven mediocre, and, at the time of the 1836 presidential election, his star had fallen so far that the best he could do for himself was as the clerk of the Hamilton County, Ohio, Court of Common Pleas. No one was more surprised by his sudden elevation than the man himself. “Some folks are silly enough,” he wrote to a friend, “to have formed a plan to make a president out of this clerk and clodhopper.”

The Whigs were so encouraged by Harrison’s showing in that election—he finished second to Martin Van Buren in a four-way race—that they ran him again four years later. The party repackaged this Virginia-born, mansion-owning son of a signer of the Declaration of Independence as a log-cabin-dwelling, cider swilling commoner. The “Tippecanoe and Tyler, Too” campaign, with its colorful slogans, songs, rallies and mass merchandising, was transparently superficial. But most voters didn’t mind: Old Tip beat Van Buren in the 1840 election rematch.

Vanity was Harrison’s weakness. Despite his self-deprecating assessment of his candidacy, he was a man who bought into his own hype. Throughout his campaign, critics had derided the general as too old and feeble to serve as president. The thin skinned Harrison sought to prove them wrong, even though they were right: He suffered a chronic digestive disorder and had lain near death from malaria seven years earlier. Regardless, he took great care at public appearances to project an image of health and vigor. This often meant appearing without cover or overcoat, as he did during his inauguration, a day when it pelted rain on and off while a brisk wind chilled bodies. It was just more of the same miserable weather that had followed Harrison from Ohio. He was possibly carrying a cold already. Riding horseback in the parade, exposed to the elements, only made it worse.

The procession routed the dignitaries inside the warm, dry Capitol, where Vice President John Tyler took his oath in the lower chamber. During Tyler’s ceremony, Harrison made his rounds in the upper gallery, receiving well-wishers and upstaging the man who, as events transpired, would fill three years and 11 months of Old Tippecanoe’s term.

Back outside, the old soldier stood on the Capitol’s east portico to address the crowd. Harrison had penned a lengthy speech during his travels. Ordered by his handlers to say little during the campaign, he aimed to use the address to unleash every thought he had about government and politics. Further, he angled to quell the perception that he was an intellectual lightweight. Pretentious references to the Helvetic Confederacy, ancient Athens and the Roman Republic filled his text. According to incoming Secretary of State Daniel Webster, who was shown the speech in advance, “it had no more to do with the United States than a chapter in the Koran.” Webster had pleaded for permission to edit the text before its delivery, and the president-elect consented. The secretary of state worked frantically, slashing copy laden with words such as “proconsul.” After this lengthy editing session, Webster appeared late for supper at his boarding house, looking exhausted. Asked if anything was wrong, he quipped: “I have killed seventeen Roman proconsuls. Dead as smelts—every one of them!”

Even with Webster’s cuts, the 8,445- word text remains the longest inaugural speech in American history. It took Harrison one hour and 40 minutes to deliver. The partisan reports of the day were selective in their accounts. The pro-Whig National Intelligencer complimented it for its thoroughness. Anti-Whig papers pointed out that most of the audience members lost interest as the speech droned on and they began walking around and talking among themselves. After Harrison was sworn in by Chief Justice Roger Taney, a servant stepped forward with the new president’s hat and cloak. Only then did he properly clothe himself from the elements. A brief Senate hearing to confirm his Cabinet selections followed. Then, he remounted his horse and began the parade procession back down Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House.

Arriving at his new home, he was feeling poorly. He rested upstairs for half an hour while his forehead was massaged with alcohol. Then he dutifully stood downstairs for three hours in a receiving line. Guests were disappointed when they learned the new president was too fatigued to shake hands and they would have to settle for a polite nod. The exuberance of the day gave him his second wind. He went out into the night by carriage to three separate balls, and created excitement when he danced at each. Not since George Washington had a president participated in the dancing at his own inauguration. The day ended late, and the new president was exhausted. Climbing into bed, he complained about not feeling well, but brushed aside a servant’s concern by saying, “It’s just a chill.”

Days in Office

Harrison began his term less prepared than any man before him. In the early years of the presidency, Congress provided the chief executive a salary, a furnished home and little else. It was left to the individual to provide his own personnel and materials for maintaining the White House and the executive department. Stating his preference to give full attention to the pre-inaugural festivities, Harrison ignored advice given months in advance that he should have an administrative infrastructure in place before he took over. Other than selecting a Cabinet, he was content to begin his first day more or less from scratch. He would regret this decision. As many as 18,000 jobs were potentially up for grabs with the change of administration. Citizens who had a stake in these jobs had been pouring into town for weeks: Whigs looking for spoils, ex-officeholders hoping to resume careers after 12 years of Democrat rule, friends of friends bearing letters of introduction. This mob was waiting for the president as he began his first hour on the job. With no system in place to organize or screen these applicants, the White House hallways became a scene of mayhem. Whenever the president was spotted moving from one room to the next, the mob erupted with shouts, each individual desperate to be first with a request lest someone else beat him to it. It was Harrison’s nature to want to grant each individual five or 10 minutes of his time. This press of humanity kept him from attending to all other matters during the day, and he and his Cabinet members found themselves working late into the evenings to keep pace with their workload.

The White House remained chaotic for the rest of Harrison’s time in office. Witnesses recalled the sad spectacle of the president of the Unites States climbing a staircase to be seen and heard, pleading to the mob to show some consideration. Others tell of the day the hallways were so thick with petitioners that Old Tip, to get from one room to another, was helped out a window so he could walk the length of the building and re-enter through another window.

He had no one to blame for his dilemma but himself. Harrison craved popularity. He seldom said no to a request. Throughout his campaign and the post-election season, he had been handing out promises like candy. In many cases, the same job had been promised to more than one person. One White House dinner guest provided a snapshot of a president stressed by the pressure of meeting so many demands: “The poor old man was bursting and fidgeting about—running out three or four times into the dining room…the dinner was scarcely over before the old man began giving toasts.”

Adding to his worries was his own political party. The Whigs’ platform called for a weak chief executive who would defer to the will of the Whig-controlled Congress. In Harrison they believed they had found their perfect figurehead president—eager to please, malleable and lacking in political savvy. Yet the new president was an ex-military man used to giving—not taking— orders. In the first days of his term, he found himself pushed to a breaking point by the party’s two most prominent figures, Secretary of State Webster and Senate leader Henry Clay of Kentucky.

Both Webster and Clay sought undisputed leadership among the Whigs and each angled to undermine the other’s influence with the new president. Getting their own supporters appointed to key administrative positions was crucial to each man’s objective. Harrison was torn between his desire to give both men their due, and yet not provide ammunition to his critics who saw him as nothing more than a Whig puppet.

As a member of the Cabinet, Webster had an advantage, but he overplayed his hand when he tried an end run around one of Harrison’s own appointments. The president had no choice but to reprimand his secretary of state, and he did so in front of the entire Cabinet, much to Webster’s humiliation.

More difficult was dealing with Henry Clay. As a fellow “Westerner,” the Kentuckian had used his influence to secure for Harrison virtually every political office he had ever held. Both men felt a debt was owed. After his election, Harrison confessed how awkward he felt to now be in a position of authority above the legendary statesman. Clay was offered his choice of any role in the new administration, but declined, believing he could wield more power by remaining in Congress and dictating Harrison’s presidency from Capitol Hill.

Notoriously cocky, Clay had boasted to his Senate colleagues that for the next four years he essentially would be president in all but title. He provided the president with lists—more as demands than as suggestions—for office appointments, and felt betrayed when it became obvious Harrison was giving equal consideration to Secretary of State Webster. Even more important to Clay, however, was using the administration to settle old scores against the party of his longtime nemesis, Andrew Jackson. Indeed, the guiding spirit of the Whig Party had evolved out of Clay’s unsuccessful challenge to Jackson’s reelection in 1832. Now with his Whigs finally triumphant, Clay was like a kid waiting for Christmas in anticipation of dismantling the programs of the rival Democrats. Every chance he had he pressured Harrison to call for a special session of Congress at the earliest opportunity.

When the matter was brought before the Cabinet, they voted no, with Harrison making the tie-breaking decision. Webster had urged the president that such a session should be delayed until the divided Whigs could work out some basic differences, although the secretary of state’s higher motivation may have been merely to thwart Clay’s influence. Clay was appalled that the president had refused his suggestion. Like a professor correcting an errant student, the senator shot off a formal letter to Harrison, pointing out how the new president had made a mistake and, enclosing a draft of a proclamation that Clay had written, how he should rectify the matter. Harrison was indignant. “You use the privilege as a friend to lecture me,” he wrote back, “and I take the same liberty with you: you are too impetuous. Much as I rely upon your judgment, there are others whom I must consult.” Stung, Clay stormed out of Washington in a huff. Webster likely smiled at this victory, but, regardless of the Kentucky senator’s methods, Clay had been right: An early session was necessary if for no other reason than to address the economy. Two days later, on March 17, after other Cabinet members prevailed on the president to reconsider, Harrison issued a call for a special session of Congress to convene at the end of May. It would prove to be the only significant executive order of his term.

The President’s Health Worsens

The Washington, D.C., of the mid-19th century was far from the urban metropolis it is today. The city was described by one contemporary as “a great village, with houses scattered here and there.” One did not have to venture far from the government buildings before encountering a rural hamlet. A quarter-mile away from the White House, on swampy land between 7th and 9th streets, were the so-called “marsh markets,” where vendors peddled fresh foodstuffs from the local farms. No one seems sure why the president himself went there several mornings each week to shop for the White House groceries. Some say it was a calculated move by the Whigs to project the country’s leader as a simple man of the people. Others suggest it reflected Harrison’s unpreparedness—there was no one else to do the shopping. (This seems unlikely. Harrison had traveled from Ohio with a retinue of cronies and family members—though not his wife, Harriet. She would wait to travel after the spring thaw.) More probable is that these excursions provided an opportunity to escape the madness at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. Strolling with a simple shopping basket on one arm, the president invariably drew a crowd. But it was his kind of crowd— ordinary citizens eager to gaze upon the city’s newest, most famous resident. A contemporary journalist reported on Harrison as “an elderly gentleman dressed in black, and not remarkably well dressed, with a mild benignant countenance, a military air, but stooping a little, bowing to one, shaking hands with another, and cracking a joke with the third.” Many mornings he would invite a new acquaintance to accompany his return to the White House and share breakfast. Eventually, though, the office seekers began pursuing him at the markets. It seemed there were few places the president could find peace. Even his attendance at two local churches each Sunday was as much spectacle as spiritual.

The constant pressure from crowds, office seekers and politicians and a lack of rest were wearing the aged man down. Living in a 40-year-old leaky and drafty oversized house did him no favors, either. A rudimentary furnace system installed in the basement during the Van Buren years was not up to the task of warming the second-floor living quarters. A travel writer of the period recorded: “[The White House] is built upon marshy ground, not much above the level of the Potomac, and is very unhealthy. All that live there become subject to fever and ague.” This situation did not suit well a man who was trying to shake a cold.

Still, the exuberance of being president somehow sustained Harrison’s energy. Accounts suggest a very visible, active executive. He kept true to his intention to pay personal visits to each government department. He held a reception for a corps of foreign diplomats. He posed for a daguerreotype, the first known instance of a sitting president being captured in a photograph. Most nights the White House hosted informal gatherings for family, friends and political insiders. Such occasions were described by participants as “regular hard-cider affairs.” Adhering to the old saw about “feeding a cold,” the president ate and drank copiously. Writers record him as talking loudly across the table, being “full of obscene stories about war and lechery.” Eyebrows were undoubtedly raised when Harrison gave dour ex-President John Quincy Adams a hearty slap on the back. Despite his Virginia Tidewater upbringing, 30-plus years of living in the Western states had apparently rubbed off on Old Tip.

President Harrison Dies

March 26, 1841, was the 23rd day of Harrison’s presidency. There are varying accounts of his whereabouts that Friday morning. Some have him horseback riding. Others have him walking back and forth between government buildings or, perhaps, shopping at the marsh markets. Regardless of his activity, he was caught in a torrential downpour without cover, and returned to the Executive Mansion drenched to the bone and shivering. Although popular legend has Harrison catching his deadly cold while delivering his lengthy inaugural address, it is equally probable that this late March drenching was the catalyst behind the president’s final illness.

Attempting a normal workday, Harrison felt progressively worse. The following day after dinner, he finally conceded that his critics had been right: The duties of the office were too much for a 68-year-old, ailing man. A physician looked him over. The president was ordered straight to bed, where he was warmed with hot drinks and mustard packs. When his chill continued the next day, additional doctors were brought in.

In 1841 medical science had yet to establish germ disease theory. Instead, the prevailing wisdom was that a patient’s body needed to be purged of the internal malady that was causing illness. All too often the excessive cures administered by well-meaning physicians only made matters worse. This seemed to be the case with Harrison’s doctors, who incorrectly diagnosed right lower lobe pneumonia. His bed shirt removed, the patient was propped on his left side and scalding metal cups were pressed, rims down, on his bare torso. As the cups cooled, a vacuum created suction that, along with the heat, produced blisters on the skin that were then lanced. The belief was that this would draw out the disease in his lungs.

When this painful remedy produced no improvement, the purging moved to other areas of the body. Doses of ipecac were given to induce violent vomiting. Castor oil and calomel were used to flush out his bowels. This only made the president weaker against his infection. In desperation, ancient Indian remedies were tested. A boiled mixture of crude petroleum and Virginia snakeweed—an American Indian treatment for snakebites—was forced down his throat. For his pain, he was plied with opium, brandy and shots of whiskey at regular intervals, all of which kept him inebriated. His speech became incoherent, his mind hallucinated. “I cannot stand it…I cannot bear this…don’t trouble me,” he was overheard moaning. It was not clear if he was referring to the doctors with their various remedies, or experiencing a delirious flashback to the persistent office seekers, who so recently had hounded him.

There was no official announcement that Harrison was ill. But the longer this very public figure remained out of view, the stronger the speculation grew. Curious crowds gathered outside the president’s home, awaiting any kind of news. A White House doorman offered unconvincing reassurances. Administration activity ground to a halt. Office seekers were put on hold. Government officials wandered the White House rooms, checking in on a bedridden figure who had trouble recognizing them. His family remained secluded, worried and in disbelief.

On Wednesday, March 31, the National Intelligencer printed a small news item with an optimistic spin, but like so much that had been written about Old Tippecanoe, it was pure fantasy. In his second-floor bedroom, his condition sank daily. Pale and too weak to move, Harrison sensed the end was near. “Ah, Fanny,” he moaned to a nurse on April 3, “I am ill, very ill…much more so than they think me.” Later that day doctors informed family members and government officials that the president would not live much longer.

After spending nine days in bed, William Henry Harrison passed away in the early morning hours of April 4, one month to the day after being sworn into office. The cause of death was recorded as “pleurisy,” but a post-mortem exam suggested that for all their efforts, the doctors had also induced hepatitis in their patient.

The United States was suddenly without a Chief Executive. Never before had the government needed to address the issue of succession in case of a president’s death. The Constitution merely specified that in such event, “the powers and duties of the said office…shall devolve on the Vice President.” The vagueness of this wording left the issue open to interpretation. Some Whigs believed it meant the office should remain vacant and the president’s chosen Cabinet should continue to govern by committee, with the vice president as “acting President.” Vice President John Tyler, to the outrage of many dissenting voices, took matters into his own hands: He ordered a judge to administer the presidential oath to him. There was nothing in the Constitution to argue either for or against this maneuver. Lawmakers realized it was necessary to clarify this constitutional oversight. Strangely enough, by dying while in office and forcing the debate on presidential succession to the forefront, President Harrison had made the most important contribution of his administration.

Harrison’s Legacy

The news of Harrison’s death was greeted with shock as it spread across the country. Many Americans still believed they had elected a sturdy, robust old warrior. Accounts of him vigorously astride his stallion during the inauguration were fresh in their minds. For some in Washington, there was a more philosophical take. Because of the fractious nature of the Whig Party and antebellum-era politics, some believed an early death had done the old man a favor. After the May 31 special session of Congress, called by Harrison before his death, a Virginia representative observed that had the president lived just another two months, “he would have been devoured by a divided pack of his own dogs.”

However, not everyone was displeased. Andrew Jackson, getting the news in Nashville, Tenn., was ecstatic. The ex-president, who had openly referred to Harrison as “the imbecile-in-chief,” saw it as a sign that God was likely a Democrat. “Providence,” he declared, had vindicated his own policies and protected the nation by removing “a President…under the dictation of the profligate demagogue, Henry Clay.”

In Ohio, first lady Harriet Harrison had only recently received word that the president was ill. She was making hasty arrangements to travel to the nation’s capital when news arrived that her husband was dead. By the time citizens in the far reaches of the Western territories got the news, the man they called Old Tippecanoe had already been buried.