To be an accomplished person in Stalin’s Russia was always to court danger, never more so than on the eve of World War II. In 1938, in a paroxysm of paranoia, the Soviet secret police arrested and shot on Stalin’s orders nearly every top army and navy commander, every prominent Bolshevik political figure, thousands of writers and intellectuals, and hundreds of thousands of once-prosperous peasant farmers and other “anti-Soviet elements.”

To be an accomplished person in Stalin’s Russia was always to court danger, never more so than on the eve of World War II. In 1938, in a paroxysm of paranoia, the Soviet secret police arrested and shot on Stalin’s orders nearly every top army and navy commander, every prominent Bolshevik political figure, thousands of writers and intellectuals, and hundreds of thousands of once-prosperous peasant farmers and other “anti-Soviet elements.”

Sergei Korolev fit none of these categories, but his accomplishments—even in a field too obscure at the time to have gained him prominence in either political or scientific circles—had still earned him his share of rivals. Originally trained as a carpenter at a vocational school in the years following the revolution, Korolev had become fascinated by airplanes; by 1930 he had earned both his pilot’s license and an engineering diploma. That year he went to work for the famed Russian aircraft designer Andrei Tupolev.

But it was the vision of space travel that had really captured the young Korolev’s imagination, and within two years, at age 25, he was leading a pioneering Soviet research group exploring rocket and ramjet engines. The following year, 1933, the group launched a successful liquid-fueled rocket.

The Propulsion Research Group (GIRD in the Russian acronym) was soon the largest rocketry research group in the world, experimenting on futuristic technologies such as cruise missiles, manned rocket-powered gliders, and gyroscopic autopilots. Korolev’s team also perfected a crucial, and now standard, method of cooling a rocket engine by diverting liquid oxygen through a series of pipes en route to the combustion chamber. In much of this work GIRD was years ahead of German scientists, anticipating many of the key technologies that would later go into the Nazis’ V-weapons.

Korolev was a driven man, an ascetic who did not drink and a cynic whose favorite expression was, “We will all vanish without a trace.” But neither his realism nor his toughness saved him from Stalin’s purges: in 1938, along with a half-dozen key scientists and engineers at his institute, he was anonymously denounced for sabotaging the work and was taken to the notorious Lubyanka prison, where he was tortured until he produced a confession. The institute’s director and deputy were shot; Korolev got off with a 10-year sentence and was sent to a labor camp in Siberia where he was set to work mining gold 12 hours a day. The man who would much later be revealed as his accuser became the new director of the institute.

Korolev’s jaw was broken by his interrogators; in Siberia he developed scurvy and lost all of his teeth. Then, shortly after Germany invaded Poland, he was sent back to Moscow, given a new “trial” that reduced his sentence to eight years, and handed over to one of the most bizarre institutions of the Stalinist regime: a sharashka, basically a slave labor camp for intellectual workers. There, together with his old mentor Tupolev (who had also been denounced), he was assigned to work on the design of what would become the Tu-2 bomber, a superb aircraft whose speed, range, and payload was never equaled by any other medium bomber that saw service during the war.

In 1944 Korolev was finally released; he returned to work on rocket engines and was part of the Soviet team that swept into Germany in a race against the Americans to scoop up information—and scientists—from the V-2 project.

Only once did Korolev talk about his experiences in the gulag. It was the day he was reunited with his family, and he stayed up most of the night telling of his ordeal. “Never ask me again about it,” he told them when he was done. “I want to forget it all like a horrible dream.”

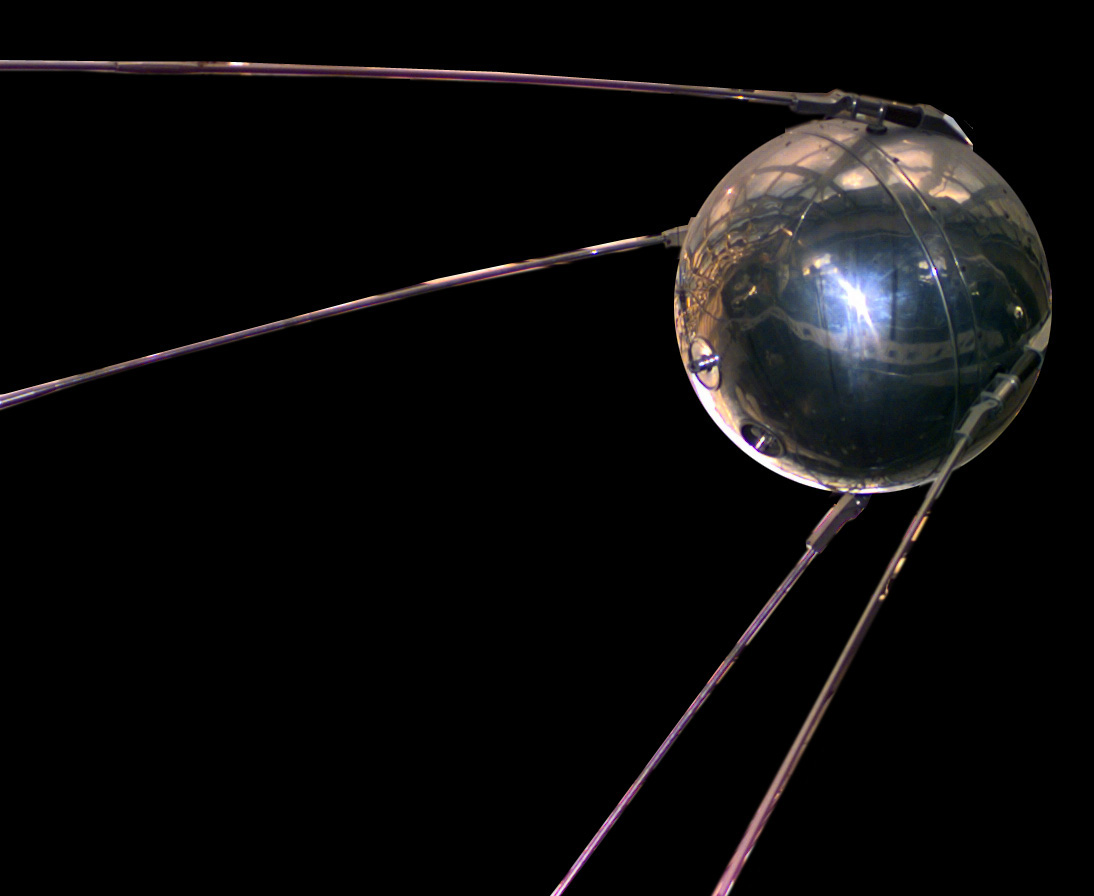

Korolev’s triumphant rehabilitation after the war would be as anonymous as his degradation during it: as head of the Soviet space program and the driving force behind the Sputnik and Vostok projects that placed the first satellite and the first human in earth orbit, he was identified only as “the chief designer,” his name kept secret from the world until his death in 1966.