In the first episode of the HISTORY Channel miniseries The Men Who Built America, the observation is made that before the Civil War America’s leaders, the men who shaped the country, were all in the political arena. After the Civil War, they were businessmen. As Richard Parsons, the former CEO of Citigroup and Time Warner who is one of the commentators in the series expresses it, “It wasn’t by accident that the 20th century became … the American century.”

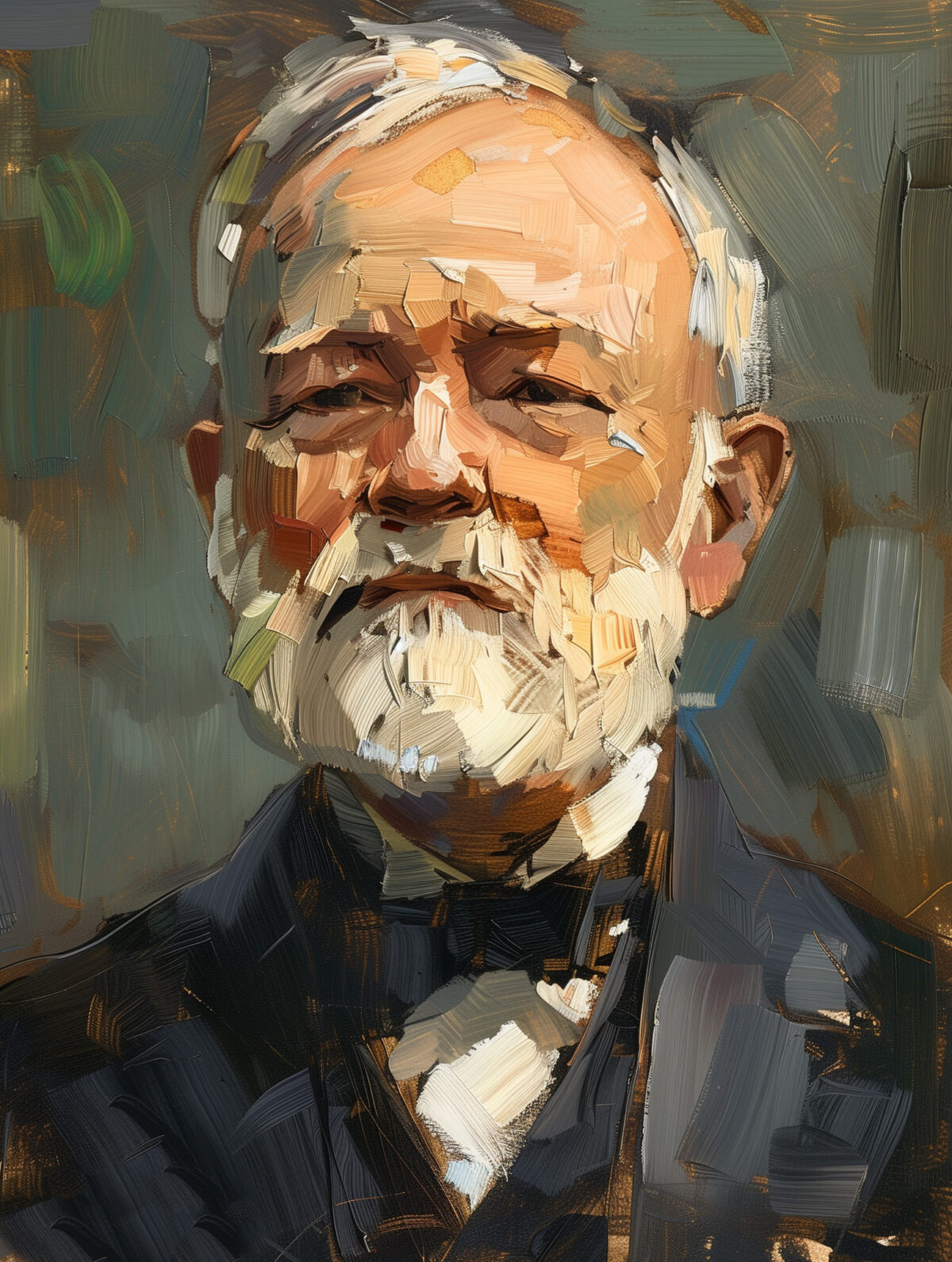

This eight-hour series premiers at 9 p.m. Eastern Time on October 16 with back-to-back episodes; other episodes will be broadcast on subsequent Tuesday evenings at the same time. The series focuses on “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt (shipping and railroad magnate), John D. Rockefeller (oil and its derivatives), Andrew Carnegie (steel), Henry Ford (automobile manufacturing), and J.P. Morgan (finance).

When American schools teach about these men they usually are treated as distinct from each other, lumped together only as highly successful capitalists of the second half of the 19th century. Once lionized as giants of capitalism and stellar examples of the American dream come true, today they are often demonized as robber barons who monopolized trade and exploited workers.

The Men Who Built America examines both sides of that coin. It explores not only their individual accomplishments and the influences that drove them to succeed on a grand scale, it also shows how their paths crossed and how they affected each other’s lives and businesses. If the entire series is like the first episode, which HistoryNet screened, viewers will find themselves saying frequently, “I never knew that!”

This is the story of men who rose from obscurity—even poverty—to become giants. It is about visionaries; indeed, the greatest asset these men have in common is their ability to imagine the future and see how they can triumph within it. This is not a “warm fuzzies” rags-to-riches tale, however. To reach the pinnacles they see for themselves, they must be utterly ruthless, letting nothing and no one come between them and their dreams. One of the program’s commentators, media magnate (Viacom) Summer Redstone, says, “Now, naturally if you win big in business, money follows, but that shouldn’t be your objective. Your objective should be to win. And money will follow if you’re successful in business.”

The first episode is, to a significant extent, the story of big fish eating not just little fish but other big fish as well. When Vanderbilt’s competitors unite their railroads against him, he closes the Albany Bridge, which he owns, the only rail route to the ports of New York City. Unable to move goods and passengers, his competitors lose money, their stock falls, and Vanderbilt buys it up to take over their rail lines.

To insure his railroads will always have sufficient goods to transport, and realizing that oil and its derivatives such as kerosene comprise the fuel of the future, Vanderbilt makes a deal with a struggling young entrepreneur in Cleveland named John D. Rockefeller. Rockefeller doesn’t explore for oil—too risky—he improves methods of capturing and refining it. The deal gives Vanderbilt exclusive rights to transport Rockefeller’s oil products and allows Rockefeller to rise above his own competitors until he owns 90 percent of America’s oil. But like Frankenstein’s monster, he turns against his creator and makes deals to undercut the Commodore. Vanderbilt then allies with his own biggest rival and refuses to transport Rockefeller’s oil.

To bypass the railroads, Rockefeller creates an interstate pipeline, an unprecedented project. Two railroad partners, Tom Scott and Andrew Carnegie, attempt to build their own pipeline in Pennsylvania. In retaliation, Rockefeller shuts down his refineries in Pittsburgh, costing himself millions but destroying Scott and Carnegie’s rail company, which has to lay off thousands of workers—when elephants fight, the small animals get trampled. In Pittsburgh, some of those workers riot, attacking the rail company and burning nearly 40 buildings. Labor unrest will play a larger role in later episodes of the series, when the giants of capitalism are confronted by workers demanding higher wages and reformers attacking business trusts.

The debut of the series is well-timed, coming as it does when Americans are again sharply divided over business regulations versus laissez-faire capitalism, supply-side (or trickle-down) economics versus higher taxes on the wealthy, and the growing disparity in income between those on the top economic rungs and those farther down the ladder.

The series shows the inherent conflict in a capitalist society: visionaries and innovators need freedom and flexibility to make their Big Idea a reality, which will create jobs and stimulate economic growth; without restrictions, however, those same visionaries will crush competition and stifle innovation and the growth of other businesses. Even Vanderbilt falls prey to the lack of regulation on Wall Street when Jay Gould and Jim Fisk, owners of the Eire Railroad, simply print more stock in their company as he tries to buy a controlling interest, costing him millions.

The Men Who Built America is a docudrama, with actors in the roles of the industrial and financial giants and their competitors. “Talking heads” commentary provides insight and additional information. Among the most recognizable commentators are Donald Trump and Senator (D-W.Va.) John D. “Jay” Rockefeller IV. Additionally, HISTORY says the series utilizes “state of the art computer generated imagery that incorporates 12 million historical negatives, many made available for the first time by the Library of Congress.”

There are some beautiful scenes of trains steaming through lush, verdant countryside. Scenes shot at historic sites such as Harpers Ferry and the Strasburg Rail Road stand in for 19th-century locations no longer in existence. Unfortunately, there are also an annoying number of scenes of the main characters walking in slow motion at locations that represent their business interests, used ad infinitum like characters in the old Hanna-Barbera cartoons running past the same background scenery over and over.

The amount of time spent after commercial breaks to recap what occurred in the previous 15 or 20 minutes also gets old quickly. This eight-hour series could probably have been cut to seven or less by eliminating these extensive recaps in every section of each episode.

The creators of any history-based program invariably have to be selective about what facts will and will not be included, but it is curious that in the first episode we are told about Vanderbilt creating Grand Central Station, the largest train depot in the world, and owning more miles of rail lines than anyone else in the world, but no mention is made about him financing the creation of Vanderbilt University in the decade following the Civil War. The school was intended to be a Southern university that would strengthen ties between all regions of America.

Those gripes aside, The Men Who Built America is engaging and informative. It will likely stimulate renewed public interest in learning more about the men who are its focus and the times in which they lived. It may also provoke political debate—don’t be surprised if the series or the men it portrays are referenced by one or both sides in the run-up to the presidential election. Mark your calendar for October 16; this is a series worth watching.

[nggallery id=119]