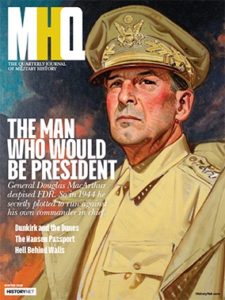

General Douglas MacArthur craved power. He also despised Franklin D. Roosevelt. So in 1944 he secretly plotted to run against his own commander in chief.

FOR NEARLY A YEAR, FROM SPRING 1943 TO EARLY 1944, GENERAL DOUGLAS MACARTHUR, the supreme commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area, conducted a series of highly confidential meetings with his most trusted aides. This would have been unremarkable but for the fact that the meetings had no military purpose. Instead, they were part of a concerted, coordinated effort, involving numerous active-duty Regular Army professionals and many hours of the commander’s time, to win MacArthur the White House in 1944. Even as MacArthur crafted grand strategy and directed extensive military operations in New Guinea, he was secretly scheming to fulfill his dream of becoming president and removing from office Franklin D. Roosevelt, a man for whom he felt mostly antagonism and contempt.

MacArthur began his sotto voce campaign by maneuvering for the 1944 Republican presidential nomination. Ever since his days as the army’s chief of staff in the early 1930s, MacArthur had been cozy with the political right, and he had nursed presidential ambitions for at least that long. He was especially popular with isolationists—who seemed oddly indifferent to MacArthur’s moderate internationalist views—and midwestern conservatives who opposed Roosevelt’s New Deal.

By 1942 MacArthur was a national hero, having become a powerful symbol of defiant resistance during the disastrous U.S. military campaign in the Philippines. There, after Japanese forces surrounded the island of Corregidor, MacArthur and his family and a small group of aides had broken through the enemy blockade in a PT convoy and made their way to Australia, where, on the president’s orders, he was to organize the Allied counteroffensive.

Stoked by self-promoting, fantastical communiques from his headquarters in Melbourne and, ironically enough, pro-MacArthur propaganda pumped out by the Roosevelt administration, the general’s legend with the American public grew to Bunyan-esque proportions, morphing into a politically potent cult of personality.

From New York to North Carolina, new parents named their baby boys Douglas MacArthur. Streets were renamed after him, as were parks, buildings, and even dams. The town of MacArthur, North Carolina, received a new post office on the strength of its name alone. A Democratic senator urged FDR to rename Corregidor—the fortress in the Philippines that MacArthur had abandoned in 1942—MacArthur Island. State legislatures, governors, and politicians from all over the country fell over themselves to prepare resolutions to honor MacArthur. Newspaper headlines routinely referred to him as “The Lion of Luzon.” Congress designated June 13 as national “Douglas MacArthur Day” to commemorate the storied day in 1899 when the great man had entered West Point. The general received scores of honorary memberships in clubs and societies from coast to coast, and an honorary doctor of laws degree from the University of Wisconsin. The Blackfeet Indian tribe adopted him as a member. The National Father’s Day Committee chose him as “Number One Father for 1942.” Enterprising merchants peddled MacArthur lapel buttons. Fawning authors highlighted his stellar record as a West Point cadet, his bravery during World War I, and his rapid ascent as a career military officer in books with titles such as MacArthur the Magnificent and General Douglas MacArthur: Fighter for Freedom.

Newspapers all over the nation rushed to join in the adulation. “There could be no more popular man in America today than General MacArthur,” the Santa Cruz Sentinel gushed. “His daring, spectacular, stubborn and wily exploits have set him up as an American model.” To the Billings Gazette, MacArthur was “America’s foremost hero—a tactician, scholar, soldier, and man of keenest insight into American and international problems.” The Baltimore Sun, branding MacArthur “a military genius,” said that the general had “some conception of that high romance which lifts the soldier’s calling to a level where on occasion Ethereal lights play upon it.”

Riding the wave of hero worship that had swept through the country during the Philippines campaign, MacArthur had become a powerful symbol to many anti-Roosevelt voters, politicians, and editorialists who came to see him as more competent than the president on military matters and more devoted to America’s true best interests. Pro-China politicians, a longtime force in the Republican Party, liked his commitment to an “Asia First” strategy. In their view, the “Europe First” policy had ensnared the United States in a war fought primarily for the enhancement of British and Soviet power.

As the Philippines fell to Japanese forces in March 1942 and MacArthur uttered his famous line, “I shall return,” conservatives had lobbied the Roosevelt administration to put MacArthur in charge of the nation’s global military operations, or at least the entire war effort against Japan. Some, like Joseph C. Harsch of the Christian Science Monitor, even hinted that the administration had deliberately divided the theater command and starved MacArthur of resources “partly because of jealousy of MacArthur’s great popularity and partly because the conservative opposition press launched a MacArthur-for-President campaign.” For almost two years, the general’s Southwest Pacific Area headquarters did little to discourage such talk, even as it churned out a succession of press releases emphasizing MacArthur’s disinterest in elective office.

“I have no political ambitions whatsoever,” one such communique, issued in MacArthur’s name on October 29, 1942, said. “I started as a soldier and I shall finish as one. The only hope and ambition I have in the world is for victory for our cause in the war.”

THE FIRST RUMBLINGS OF MACARTHUR’S UNDER-THE-RADAR CAMPAIGN FOR THE PRESIDENCY came in March 1943, when he sent Major General Richard K. Sutherland, his devoted chief of staff, to Washington for meetings aimed at developing a grand strategy for future Pacific operations. Sutherland—brusque, cold, brilliant, and ruthless—shared his boss’s political conservatism. In Washington he met with Clare Boothe Luce, who had just been elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as an anti-Roosevelt Republican. She was, of course, the wife of Henry Luce, who controlled the conservative, pro-Chinese Time-Life media empire. Sutherland knew Mrs. Luce well, as she had written an adulatory profile of MacArthur that was featured on the cover of Life magazine on December 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

Luce invited Arthur Vandenberg, a powerful senator from Michigan and the very soul of midwestern isolationism, to her Washington apartment for a dinner with Sutherland. Though no record exists of what the group discussed, the meeting seemed to ignite everyone’s excitement in a MacArthur candidacy. MacArthur himself was energized: A couple of weeks later, he ordered one of his trusted military aides to travel to Washington from his headquarters in Australia to hand deliver a secret message to Vandenberg. “I am most grateful to you for your complete attitude of friendship,” MacArthur said in the message. “I only hope that I can some day reciprocate. There is much that I would like to say to you which circumstances prevent. In the meanwhile I want you to know the absolute confidence I would feel in your experienced and wise mentorship.”

The canny Vandenberg understood exactly what MacArthur was saying between the lines: He was keenly interested in becoming president, though as an active-duty soldier he could never publicly declare these intentions or run openly for the job. He could, however, be drafted as a candidate. Perhaps with MacArthur in mind, the War Department had recently decreed that no service member could seek or be elected to public office while in uniform. At the time, Vandenberg and other Republican lawmakers had promptly accused the Roosevelt administration of a ham-fisted attempt to block potential military challengers like MacArthur. “I do not know whether General MacArthur would even consider the nomination,” said Representative Hamilton Fish III, a Republican from New York, “but I am quite sure that the Executive Department of the government has no power whatever to dictate to the free people of America whom they should nominate and elect as president.”

Fish had long been in MacArthur’s corner. In a 1942 speech, for example, he said many politicians agreed that “Republicans and anti-New Deal Democrats [were] united in opposing the fourth term for President Roosevelt and the power-hungry bureaucrats and left-wing New Dealers in Washington.” He added that he thought MacArthur should be the Republican candidate, running on a “win-the-war platform and on a one-term plank as opposed to a fourth term and military dictatorship.” Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson hastily offered that his department’s prohibition on office-seeking didn’t apply to MacArthur—for what reason he did not explain.

Through 1943 and early 1944, Vandenberg took the lead in establishing an underground campaign to secure the nomination for MacArthur. General Robert E. Wood—a former quartermaster general of the army who’d gone on to become the wealthy chairman of Sears, Roebuck and

Company and a key financial backer of the America First isolationist movement—agreed to bankroll the effort. Vandenberg lined up what he called a “cabinet” of key supporters that included John Hamilton, a former chairman of the Republican National Committee, as campaign chairman, and conservative newspaper publishers Frank Gannett, Roy W. Howard, and Colonel R. Robert McCormick, a longtime friend of MacArthur’s, to handle publicity. Despite MacArthur’s popularity, there were still two leading contenders for the GOP nomination: Wendell Willkie of Indiana, who had been the party’s standard-bearer in 1940, and Governor Thomas E. Dewey of New York, a liberal internationalist. (Dewey would be famously derided as “the little man on the wedding cake” for his slick black hair, toothbrush mustache, and dapper dress.) Vandenberg hoped that the MacArthur forces might deadlock the delegate vote, paving the way to draft the general as a “finish the war” candidate who enjoyed universal respect and tremendous military prestige.

Vandenberg’s strategy for MacArthur depended on deft behind-the-scenes groundwork and manipulation. “I feel that his nomination must be essentially a spontaneous draft, certainly without the appearance of any connivance on his part,” Vandenberg wrote in his diary. “It seems to me more important than ever that we should give our own ‘commander-in-chief’ no possible excuse upon which to hang his own political reprisals. I cling to the thought that if MacArthur can be nominated it will be as the result of a ground swell and not as the result of any ordinary pre-convention political activities.”

But there was no shortage of connivance on MacArthur’s part. For starters, he designated Brigadier General Charles A. Willoughby, his intelligence officer and a man of extreme-right political convictions, to be his intermediary with Vandenberg. The two men corresponded regularly. Willoughby communicated MacArthur’s satisfaction with the efforts to secure the nomination. Vandenberg forwarded progress reports. “I am consulting with ‘our cabinet’ regarding the permanent employment of one appropriate man to take over the details of this entire undercover movement,” Vandenburg wrote in one of them. “The difficulty is in finding the right man who will fully understand the necessity for operating under ‘our rules.’ ”

During another trip to Washington, Sutherland, MacArthur’s chief of staff, met with former president Herbert Hoover to discuss MacArthur’s presidential prospects. Hoover, who viewed MacArthur as the only acceptable Republican candidate, thought that Dewey would probably win the nomination but suggested that MacArthur could be his vice president, with full powers to run the war effort. Sutherland thought his boss would be amenable to the arrangement, unrealistic as it might have been.

Back in the South Pacific, as American forces “island hopped” through New Georgia, in the central Solomon Islands, MacArthur continued to discuss his presidential ambitions with subordinates. In a June 1943 meeting with Lieutenant General Robert L. Eichelberger, one of his primary ground commanders, MacArthur mentioned his hopes of securing the Republican nomination. “I can see that he expects to get it, and I sort of think so, too,” Eichelberger noted in his diary. Years later, Eichelberger described MacArthur as having an “intense desire” to be president and added that “before the 1944 election, he talked to me a number of times about the presidency but would usually confine his desires by saying that if not for his hatred, or rather the extent to which he despised FDR, he would not want it.”

Sutherland recalled that MacArthur walked into his office one day at headquarters, after it was relocated to Brisbane, Australia, in the middle of 1942, and said: “Dick, when I get elected we will go back to Washington. I will take you with me. You will be my chief of staff. We will move into the War [Department] Building and we will run the war. I will let Congress run the country.” Another time, MacArthur reminded Sutherland that “old Zach Taylor made it to the White House and so can I.”

Colonel Lloyd A. Lehrbas, a former newspaperman who was on MacArthur’s public relations staff, felt that the general should have nothing to do with running for president. The two men regularly argued over the point. “After valiant debate, he usually came red-faced out of MacArthur’s office,” Master Sergeant Paul P. Rogers, the general’s chief clerk and stenographer, later wrote of Lehrbas.

MacArthur corresponded with politicians and politically active friends who supported his candidacy. Most of the correspondents were well-meaning admirers of MacArthur or strident opponents of the New Deal. A few of them, like retired Major General George Van Horn Moseley, were venomous extremists. Moseley, a vicious and paranoid anti-Semite whose views bordered on the fascist, had once served with MacArthur. He was convinced that the New Deal was leading to the establishment of a left-wing dictatorship in America. Now, in hopes of staving off such a possibility, he urged MacArthur to return home to campaign for the presidency. In Moseley’s opinion, “the Jews and the un-Americans” were invested in another Roosevelt victory that only MacArthur could prevent. “I beg of you to be careful as to what you say or do,” he advised MacArthur in a letter, “until you have been put in touch with the tragic situation at home.”

When First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the Southwest Pacific Area Command from late August through mid-September, 1943, MacArthur studiously avoided her, probably for fear that being photographed with her would anger his potential supporters. Even as he welcomed five U.S. senators from both parties to his headquarters in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, and hosted them for three days during a substantial operation by his troops to secure Nadzab, he forbade the first lady from joining them, on the spurious grounds that it was too dangerous. “We were old friends and she took my refusal in good part,” he wrote disingenuously. Even when MacArthur’s wife, Jean, later hosted a large dinner for Mrs. Roosevelt at Lennons Hotel in Brisbane, MacArthur did not attend. “General MacArthur was too busy to bother with a lady,” Roosevelt later wrote to a friend.

Instead of personally dealing with Roosevelt, MacArthur had Eichelberger act as her host; he served as the equivalent of a three-star babysitter during a whirlwind tour of Australia and New Zealand. Eichelberger later joked that it was “the most hazardous assignment” of his career. “It is one thing to have fortitude on a battlefield,” he said, “but quite another to face the booby traps and land mines of international diplomacy.” The assignment caused no shortage of sympathetic chuckles among Eichelberger’s many friends in the senior ranks of the army. One of them, Brigadier General Floyd Lavinius Parks, jibed, “I am convinced now that General MacArthur really knows his men when he selected super-diplomat Eichelberger for the job.”

Kidding aside, Parks was right: The job suited Eichelberger’s engaging and extroverted temperament nicely, and the visit went well. He came away impressed with Roosevelt’s warmth and eagerness to meet and talk with soldiers as she visited bases and hospitals. “She was indifferent to personal hardship, and always gracious,” he wrote. “She could not be kept out of wards where wounds smelled evilly and agony was a commonplace. These were the men, she said, who needed comfort the most. Her simplicity…endeared her to the troops; her graciousness endeared her to the Australians; and her visit stored up a reserve of good will that was like a family bank account.”

IN SPITE OF MACARTHUR’S OWN MACHINATIONS, AS WELL AS THOSE OF HIS HAND-PICKED STAFFERS, Vandenberg, and others, the general’s candidacy eventually came to nothing. Dewey proved to be too strong and Willkie too weak for any sort of delegate deadlock at the Republican National Convention. Vandenberg’s strategy depended on perfect timing and a groundswell of support for MacArthur, based primarily on emotion, at the Chicago convention in June—for the general, a political Hail Mary of sorts. He had no control over the amateurish MacArthur for President clubs that insisted on trying to place their man on the primary ballots in states where he could not hope to compete effectively. Annoyed by the organizers of these pro-MacArthur movements in the states, whom he called “self starters,” Vandenberg urged Wood and others to tamp down on them without delay.

Vandenberg was also surprised, and vexed, by the decided lack of excitement for MacArthur among returning soldiers who had served under him overseas. “I am disturbed about one thing which to me is quite inexplicable,” Vandenberg wrote to Wood. “I am constantly hearing reports that veterans returning from the South Pacific are not enthusiastic about our friend.”

Vandenberg wondered whether somehow only anti-MacArthur veterans were getting furloughs home, so he asked a constituent who was serving in the South Pacific to canvass his fellow soldiers for their opinions. The result was the same: “growing unpopularity for our friend.” The sentiments of one soldier, writing to his mother late in 1943, were fairly typical: “I guess everyone back home thinks MacArthur is some swell fellow. But the boys in the Southwest Pacific have another idea. He doesn’t do anything but ride around in his big car and live in a hotel. He doesn’t know how it is up here in the jungle.” And of course there was the derisive nickname “Dugout Doug,” memorialized in numerous ditties composed by the rank-and-file soldiers on Bataan (“Dugout Doug MacArthur lies a-shaking on the Rock, safe from all the bombers and from any sudden shock,” went one of them, sung to “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”).

Vandenberg also found that he couldn’t keep MacArthur’s grandiosity and poor political instincts in check. MacArthur had corresponded with Representative Arthur L. Miller of Nebraska, a rabid anti–New Dealer who supported the general’s bid for the presidency. “Unless this New Deal can be stopped our American way of life is forever doomed,” Miller told MacArthur. Instead of dodging such a specific domestic political issue, the general wrote back and told Miller, “I do unreservedly agree with the complete wisdom and statesmanship of your comments.”

In April 1944 Miller inexplicably released the contents of this private correspondence to the press, earning Vandenberg’s mystified fury. But the Michigan senator was even more taken aback by MacArthur’s imprudence. Soon after the correspondence was released, Vandenberg found himself talking with MacArthur’s ex-wife, Mrs. Alf Heiberg, who innocently asked him, “How’s Doug’s campaign progressing?” to which he reportedly replied, “I’m the ex-manager of your ex-husband.”

For MacArthur, the humiliation and controversy that ensued from the publication of this correspondence killed any slim hopes he might have had of a convention upset and forced him to issue a mortifying statement disavowing any political aspirations.

“I have on several occasions announced I was not a candidate for the position,” MacArthur’s statement, issued on April 30 in an attempt to pacify his howling critics, said. “Nevertheless, in view of these circumstances, in order to make my position entirely unequivocal, I request that no action be taken that would link my name in any way with the nomination. I do not covet it nor would I accept it.”

As a political amateur, MacArthur had hoped, in vain, to be carried into office by an unstoppable wave of popular support. As with so many other areas of his life, he had assumed that the customary rules of politics did not apply to him. “In private he talked a great deal in political terms, far more than other generals,” New York Times correspondent Turner Catledge, who spoke to MacArthur often about politics, recalled years later. “I believe that he was hoping for a popular avalanche of support…but I do not think that he had the stomach for campaigning. When the avalanche did not come, he backed out of the political picture reluctantly.”

MACARTHUR’S TROUBLING CAMPAIGN FOR THE PRESIDENCY, CARRIED OUT IN SECRET because he was serving in uniform and commanding troops in an active theater of war, has no parallel in American history. It is true that George Washington, Andrew Jackson, William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, Ulysses S. Grant, Theodore Roosevelt, and other one-time soldiers all made the transition from general (or colonel in Roosevelt’s case) to president. George B. McClellan tried and failed. The difference is that none of them ran while on active duty in a combat zone. MacArthur did, thus violating his soldier’s duty of apolitical obedience to civilian, constitutional authority. Not only was he disloyal and insubordinate, but his effort to defeat an incumbent president could have set a dangerous precedent for high-level military intrusion into domestic politics and civilian authority. Fortunately for him, the vast majority of the American people, and the soldiers who served under his command, knew little of his behind-the-scenes scheming for political power. In the light of posterity, though, MacArthur’s stealth campaign for the presidency revealed his dangerously megalomaniacal character.

Early in his presidency Franklin Roosevelt told an aide that he considered MacArthur to be one of the two most dangerous men in America, the other being Senator Huey Long of Louisiana. Americans would willingly trade their freedoms for the right demagogue—“the familiar symbolic figure—the man on horseback,” as FDR put it—and no one better fit that bill, he said, than Douglas MacArthur.

MacArthur would set his sights on the White House again in 1948, but this time he would be widely criticized and even ridiculed. As in 1944, though he craved the GOP nomination, he found the idea of openly seeking it repugnant. In his eyes, the nation would have to embrace him; he would not grovel as politicians did.

In defeat MacArthur denied that he’d ever had any interest in the Republican presidential nomination and maintained that the entire pro-MacArthur movement had flowed up from the grass roots. He would repeat the fiction in his 1964 autobiography.

In 1952, talking to a reporter for Time magazine, an unnamed politician explained MacArthur’s fleeting political appeal with this parable: “It’s like a guy walks up to you with a new suit on. He asks you how you like it. You say it’s beautiful. Then he says, ‘You want to buy it?’ Now, that’s a different story.” MHQ

John C. McManus is Curators’ Distinguished Professor of U.S. military history at Missouri University of Science and Technology. During the 2018–2019 academic year he has been at the U.S. Naval Academy as the Leo A. Shifrin Distinguished Chair of Military History. He is the author of more than a dozen books, including The Dead and Those About to Die—D-Day: The Big Red One at Omaha Beach (2014) and the forthcoming Fire and Fortitude: The United States Army in the Pacific War, 1941–1943, the first of a two-volume series.

For this article, MHQ is pleased to honor McManus with its first annual Thomas Fleming Award for Outstanding Military Writing. (See “Of Man and Myth,” page 32.)

[hr]

This article appears in the Winter 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: The Man Who Would Be President