Early on Sept. 13, 1847, on a rise facing Mexico City’s Chapultepec Castle, 30 men stood precariously on carts, their hands and ankles bound. Around each man’s neck was draped a noose affixed above to a long scaffold. The men were members of the San Patricio, or Saint Patrick, Battalion—mostly Irishmen who had deserted the U.S. Army to fight for Mexico. Captured and condemned by courts-martial, they were positioned overlooking the battle that raged between American and Mexican troops. The order of execution stipulated they would stand facing the smoke and fire of battle until U.S. forces triumphed. After what seemed an interminable struggle, the victors raised the American flag over the Chapultepec ramparts, and the carts rumbled away, as the San Patricios cheered for Mexico one last time. Although a subordinate general officer was likely responsible for this symbolic twist to the executions, the man who had ordered the hangings—and those of dozens more deserters—was Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott, among the most decorated, venerated and controversial soldiers in the annals of U.S. military history.

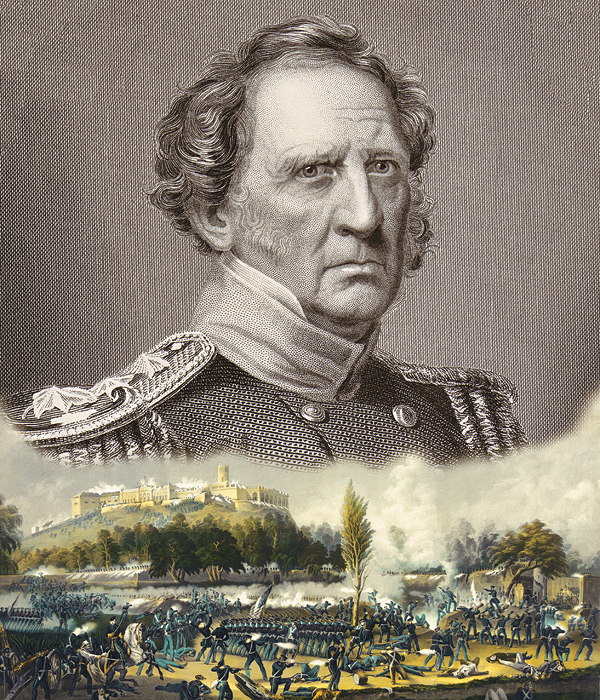

At 6 feet 5 inches and 230 pounds, Scott cut an imposing figure. When Ulysses S. Grant was a 5-foot-2-inch young cadet at West Point, he first saw Scott in all his pomp and later recalled, “I thought him the finest specimen of manhood my eyes had ever beheld.” It was an impression that would have pleased Scott, and one he spent most of his career cultivating. That extraordinary career spanned more than half a century, during which Scott served under 14 presidents—13 of them as a general officer. From 1841–61 he was commanding general of the U.S. Army, and in 1852 he ran for president on the Whig ticket. Scott wrote a three-volume drill manual that served for more than a decade as the Army’s bible on tactics. As both soldier and statesman he implemented and enforced the government’s policy of Manifest Destiny, ensuring for better or worse that only the Pacific Ocean would limit America’s westward expansion. Scott, more than any other officer, was responsible for the U.S. triumph in the war with Mexico and for conceiving a strategy that proved instrumental in securing the Union victory in the Civil War. “Old Fuss and Feathers,” as Scott came to be called, was known and widely revered for his strict adherence to the military code, fanatical attention to detail and rigid sense of discipline. He was, in short, the consummate soldier.

But Scott had a dark side. He was also known for his arrogance and his caustic tongue—traits that became evident in his earliest days in the Army. As a young and inexperienced officer, Scott displayed all the headstrong characteristics required to end his career before it started. Within two years of joining the Army he had been court-martialed and convicted of a serious offense, and had fought a duel with a fellow officer.

Scott was born in rural Dinwiddie County, Va., on June 13, 1786, to a landed, though not aristocratic, family. Both parents died before he reached age 18, leaving him with limited resources but strong initiative. By age 20 Scott had studied law and was working for a Petersburg attorney when he received news of a recent British affront. The Napoleonic wars were raging, and England, short of sailors to man its warships, was stopping U.S. commercial vessels on the high seas and pressing British-born American sailors into service aboard its warships. While England considered the practice vital to the stability of the Royal Navy, Americans took it as a flagrant breach of their rights as free men.

On June 22, 1807, the Royal Navy outdid itself. Off Norfolk, Va., the warship HMS Leopard—on the pretext of searching for deserters—pursued and attacked the frigate USS Chesapeake, killing three men, wounding 18 and impressing four sailors. News of the incident electrified Americans. President Thomas Jefferson ordered all British warships out of American waters and called upon each of the states’ governors to ready its militia. When word reached young Scott that Virginia’s governor was calling for troops, he dropped everything, bought a horse, found a uniform and attached himself to a troop of Petersburg cavalry.

Scott’s service with the militia was uneventful—although he did manage to capture a provisioning party of eight unarmed British sailors from the hated Leopard, whom superiors immediately ordered him to release. Although he returned to the practice of law, his brief exposure to military life marked a new beginning for the strapping Scott. As he himself later wrote: “The young soldier had heard the bugle and the drum. It was the music that awoke ambition.”

Within the year tensions between America and Great Britain reached the breaking point. To many Americans it had become apparent war was inevitable, and Scott desperately wanted in. What he lacked in experience he more than compensated for in self-confidence. In March 1808, through the influence of Virginia Sen. William Branch Giles, Scott—who had no military credentials whatsoever—arranged an interview with Jefferson to request an officer’s commission in the tiny Regular Army.

On April 8 Congress passed a law tripling the Army’s size, and a month later orders came through directing Captain Scott to raise a company of light artillery and report to Norfolk. The young officer immediately ordered a splendid new tailored uniform, including feathered cap, red sash and sword. When it arrived, he later recalled, he cleared the furniture from the largest room in his house—except for a mirror at each end—donned his new outfit and spent the next two hours strutting around the room, admiring his reflection from all angles. Vanity was a trait that never left him.

Scott reported to Army headquarters in New Orleans in April 1809 and almost immediately ran afoul of military regulations, with dire consequences. Congress had enlarged the Regular Army by eight regiments, but it still numbered only a few thousand men—a small fraternity facing a potentially large war. What is worse, the command of 2,000 Regulars fell to Brig. Gen. James Wilkinson. He was a self-serving rogue and, according to one historian, “the one man who habitually exceeded the ethical and often even the legal bounds.” A few years earlier Wilkinson had allegedly partnered with Aaron Burr in the dubious empire-building scheme that landed Burr in court facing charges of treason—and it was his former cohort Wilkinson who ratted on him. During the Revolution, Wilkinson had joined in a conspiracy to replace George Washington as commander in chief. And for years he had engaged in illicit relations with the Spanish government over commercial access to the new and rich lands of the Louisiana Purchase. At one point he even swore allegiance to the king of Spain and promised to close the Mississippi River to American shipping. For eight years he received an annual pension of $2,000 from Spain, and later—while serving as commander of American forces in the West—he managed to extort another $12,000 from the Spanish government. In 1808 he faced a congressional inquiry for accepting these bribes. Yet, somehow, the portly Wilkinson always managed to land on his feet. And now he stood in command of the force to which the idealistic young Scott had pledged his “life, liberty and sacred honor.”

As a lawyer, Scott had observed much of the Burr trial firsthand, and he had developed a deep loathing for Wilkinson. Wilkinson now managed to further sour Scott’s opinion of him. The local environment proved inhospitable, and Secretary of War William Eustis ordered Wilkinson to remove the army to a healthier locale some 250 miles up the Mississippi. Instead, he moved them a short distance downriver, to a fetid swamp, and supplied them with substandard provisions. One chronicler asserts the latter was “probably due to collusion with a civilian contractor.” Wilkinson also reportedly kept a Creole mistress in New Orleans whom he was reluctant to abandon. Within weeks most of his men were suffering from a variety of maladies. Hundreds perished, while others deserted or resigned their commissions. Of his 2,000-man force, only 600 remained fit for duty.

Scott resigned his commission in disgust and returned to Petersburg to practice law, but not before making several indiscreet comments about his commanding officer. When word of Wilkinson’s actions reached the War Department, he was replaced by fellow brigadier Wade Hampton and ordered to Washington to face a court of inquiry. The Army was moved to Natchez, where conditions were more conducive to its survival. Meanwhile, with rumors of war circulating once again, Scott was regretting his impulsive decision, and—realizing his resignation had not been formally accepted—he dashed off a letter to Eustis, who was only too happy to have back the avid young captain. Scott once again reported to Army headquarters.

Ominously, Wilkinson had delayed leaving for the capital, and any hope the general was out of Scott’s life was dashed when the young officer arrived in Natchez to find Wilkinson not only present, but also fully aware of Scott’s intemperate remarks. Making matters worse, Scott again found it impossible to keep his opinion of the general to himself, and foolishly voiced his derision to regimental surgeon Dr. William Upshaw, a Wilkinson friend and subordinate. Upshaw promptly preferred court-martial charges against the loose-tongued captain, and on Jan. 10, 1810, Scott found himself facing charges of “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.” Upshaw also had him charged with embezzlement, in an obvious attempt to further damage Scott’s reputation.

Apparently, Scott had been so free with his comments that the testimony as to their content went virtually unchallenged. The defendant, according to one of the charges, had publicly called Wilkinson a “liar and a scoundrel.” Scott also purportedly said he “considered a man as much disgraced by serving under General Wilkinson as by marrying a prostitute.” A separate charge alleged he had threatened Wilkinson’s life by asserting that “if he went into action under the command of General Wilkinson, he would carry two pistols—one for his enemy, and one for his general.”

Scott contended his remarks were “imprudent” rather than insubordinate. No one in the courtroom doubted the nature or substance of his comments, nor apparently did Scott attempt to deny them. He merely averred that at the time he made them, Wilkinson was his “superior” but not his “commanding” officer. It was a pale attempt at lessening the severity of his actions, and the court saw right through it.

While the court ultimately threw out the embezzlement charge against Scott, his caustic tongue was another matter. Had the court convicted him of the original charge, “conduct unbecoming,” his military career would have ended on the spot. On the other hand, they could not simply ignore the fact he had repeatedly impugned a superior officer—although it is likely many in the courtroom quietly agreed with Scott’s assessment. The court chose the middle road, finding the indiscreet young captain guilty of “unofficer-like conduct” and sentencing him to be “suspended from all rank, pay and emoluments for the space of 12 months.” Two days after passing sentence the court recommended setting aside nine of those months from Scott’s suspension; to the surprise of many, Hampton, the new commander—himself a bitter enemy of Wilkinson—refused. It was not that he resented Scott; he simply saw the need for a strictly enforced code of military discipline.

Before leaving Louisiana, Scott had one more detail to attend to. As he saw it, Dr. Upshaw had branded him a thief and then scurried to Wilkinson with reports of Scott’s remarks. His honor had been called into question, and there was only one recourse: He challenged Upshaw to a duel.

The officers met on the dueling grounds of Louisiana’s Concordia Parish, on the bluffs of the Mississippi River. Hundreds of spectators, military and civilian, watched as each man stepped off the requisite number of paces, turned and fired. Scott’s ball went wide, while Upshaw managed to crease Scott’s skull, albeit rendering minimal damage. Honor only somewhat appeased, Scott went home to serve out his suspension.

When he returned to Virginia this time, Scott devoted most of his attention to military studies. He read voluminously on history and strategy, a practice he would maintain all his life. And, remarkably, he worked to advance his career while still under suspension. Learning that the commanding officer of his light infantry regiment had died, Scott wrote to Secretary Eustis, pointing out his seniority and the fact his rank was merely under suspension. Scott argued that when his sentence was completed, he should receive a promotion to the rank of major. The secretary, no doubt dumbstruck by Scott’s brass, ignored the request, restoring him to duty as a captain in October 1811.

With the war only months away, affairs in the West were swiftly heating up between American settlers and the Canadian-based British military and their Indian allies. In early November 1811 the ambitious governor of Indiana Territory—a lanky self-promoter named William Henry Harrison—brought devastation to the village of visionary Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa (aka “The Prophet”). The action, known to history as the Battle of Tippecanoe, destroyed the tenuous peace in the Northwest, made a national hero of Harrison and paved the way for a U.S. invasion of Canada.

When Congress declared war on June 18, 1812, Scott could not have been happier. The Regular Army had swelled by several thousand recruits, and a number of states were again calling for men to fill the ranks of their militias. Hampton, realizing the main theater of action would be along the Canadian border, returned to Washington by sea and took Scott along as his aide. Stopping in Baltimore on the way, Scott discovered to his boundless delight he had been advanced two ranks, from captain to lieutenant colonel, and made second-in-command of the Philadelphia-based 2nd Artillery Regiment, under Colonel George Izard. Scott had his old sponsor, Senator Giles, to thank for the promotion.

Learning of a planned invasion of Upper Canada under the command of Maj. Gen. Stephen Van Rensselaer of the New York militia, Scott immediately volunteered to lead a two-company artillery battalion to the Niagara frontier as part of the assault force. The October 1812 invasion, dubbed the Battle of Queenston Heights, centered on the capture of Queenston, Ontario, on the Niagara River. While it went badly from the beginning, Scott performed with calm courage and skill in his first real engagement. Outnumbered and ultimately surrounded, he was forced to surrender.

Scott spent the next five weeks as a “guest” of the Crown before being paroled. Soon after arriving back in Washington in January 1813, he was promoted to colonel and given regimental command. Within months he spearheaded the capture of Fort George, and in March 1814 he was promoted to brigadier general and ordered by the secretary of war to train the army on the Niagara peninsula. This he accomplished with remarkable efficiency, improving hygiene, discipline and morale. And through incessant drilling and training he created a formidable fighting force. In early July, Scott commanded four infantry regiments and two artillery companies in the Battle of Chippawa, where his rigorous training program and brilliant strategy proved, for the first time since the war had begun, that a force of well-trained American soldiers could defeat veteran British troops.

Later that month Scott engaged the British once again, at the indecisive Battle of Lundy’s Lane. A British ball shattered his shoulder, partially incapacitating him for life. By this time his name was well known to both the military brass and the public; the 28-year-old giant had become a popular hero, in a war in which Americans desperately needed heroes.

Scott had found his true self in the field, and he would go on to ever greater military achievements, culminating in his victory in Mexico. Still, he apparently learned little of tact from his rocky first years in the Army, and throughout his life the personal failings evinced in his early career would resurface. He would continue to indulge his volatile temper, finding it impossible to curb either his tongue or his pen. He managed to offend congressmen and superiors alike—at one juncture, narrowly avoiding a duel with Andrew Jackson—and his inability to observe the finer points of diplomacy, as much as his antislavery platform, might well have cost him the presidency. From the very beginning of his military life Scott was, in the words of one historian, “too prickly to love, too talented to ignore.”

Ron Soodalter, a former columnist for America’s Civil War, has also written for Smithsonian, Civil War Times and Wild West. For further reading he recommends Agent of Destiny, by John S.D. Eisenhower, and Winfield Scott and the Profession of Arms, by Allan Peskin.