The Vickers F.B.5 has the distinction of being the first airplane designed from the outset as a fighter, built in quantity and deployed in a fighter squadron equipped with a single aircraft type. But its appearance was not much like what we would think of today as a fighter. To understand why the F.B.5 looked the way it did, it’s useful to examine both how it came to be developed and even the very definition of “fighter.”

During World War I, Britain applied the term specifically to machine-gun-armed airplanes that were designed for offensive aerial combat. British fighters were usually substantial two-seat combat aircraft, culminating in the development of the famous Bristol Fighter, or F.2B. The light, agile single-seaters that we now think of as fighters were called “scouts” by the British and were, at least at the beginning of the war, incapable of carrying any armament. Even after armed single-seaters were introduced, the British persisted in referring to them as scouts throughout the war. The designations applied by the French and Germans to their later armed single-seaters, on the other hand, were derived from their respective terms for “hunting” (avion de chasse and Jadgflugzeug). Subsequently the U.S. Army, whose members were Francophiles, literally translated the French term avion de chasse into “pursuit plane.”

The F.B.5’s story began in 1912 when the Royal Navy asked Vickers to develop an airplane armed with a machine gun. After examining the problems involved, Vickers’ designers decided the best configuration would be a fairly large single-engine, two-seat pusher. That way the gunner could be seated in the nose, where he would have a clear view ahead and an unobstructed field of fire.

The first prototype was designated the E.F.B.1 (Experimental Fighter Biplane 1) Destroyer. Powered by an 80-hp water-cooled Wolseley V-8 engine, it flew for the first time in February 1913. Unfortunately, it proved nose-heavy, which was hardly surprising considering that it carried a 60-pound Maxim water-cooled machine gun, and crashed on its maiden flight.

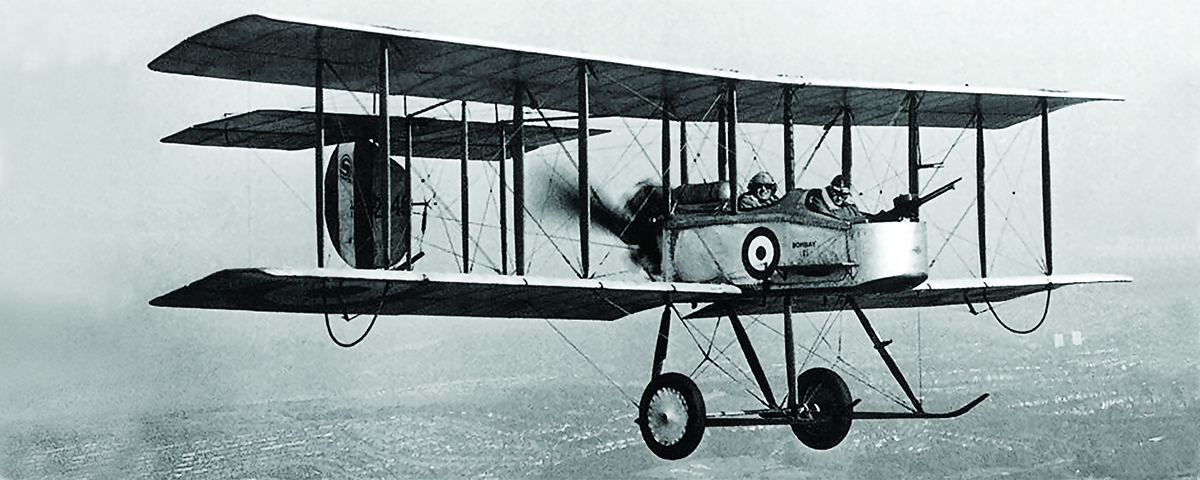

Vickers persisted with development through several subsequent prototypes. First flown on July 17, 1914, the F.B.5 was powered by a much lighter 100-hp air-cooled Gnome engine and was armed with a lightweight, magazine-fed Lewis machine gun. Like its predecessors, the F.B.5 was a two-seat pusher biplane with the gunner seated ahead of the pilot. Constructed of wood and fabric, it was 27 feet 2 inches long and had a wingspan of 36 feet 6 inches. Maximum speed was 70 mph and range was 250 miles.

Entering service with the Royal Flying Corps in November 1914 and widely known as the “Gun Bus,” the F.B.5 proved to be an effective weapon largely because there was nothing else that could challenge it. F.B.5s were initially issued individually to squadrons until July 1915, when No. 11 Squadron was deployed to the Western Front equipped entirely with F.B.5s, becoming history’s first dedicated fighter squadron. One of its pilots, Welsh-born Captain Lionel Wilmot Brabazon Rees, was credited with shooting down or at least “driving down” six enemy planes in collaboration with his gunner-observers, becoming the only Gun Bus ace.

Another 11 Squadron pilot, 2nd Lt. Gilbert Stuart Martin Insall, was flying F.B.5 no. 5074 with 1st Class Air Mechanic Thomas Ham Donald as his observer on November 7, 1915, when they forced a German Aviatik to land southeast of Arras, France. Ignoring groundfire—including shots from the downed enemy, who fled from their airplane when Donald shot back—Insall swooped down to finish off the Aviatik with a small incendiary bomb. On the way home the British airmen strafed the German trenches…until return fire holed their fuel tank. Force-landing in a wood just 500 yards behind Allied lines, Insall and Donald stood by their aircraft while German artillery lobbed shells their way. Working by flashlight and other illumination that night, the two repaired their Gun Bus and took off at dawn to return safely to their aerodrome. For their dedication to recovering the plane—literally at the risk of their lives—Insall was awarded the Victoria Cross and Donald the Distinguished Conduct Medal on December 23.

A total of 224 F.B.5s were eventually built—119 in Britain, 99 in France and six in Denmark. An additional 50 aircraft featuring a slightly improved design and designated F.B.9s were produced. As 1915 progressed, however, newer and more formidable aircraft began to appear over the front, most especially the new Fokker Eindeckers armed with machine guns synchronized to fire through the propeller. Although the Gun Bus was by then outclassed, it remained in service well into 1916.

The F.B.5 was designed to be exactly what it was, an airplane that could deploy a machine gun in the sky. Its chief disadvantages stemmed from the fact that it was designed before the war began, at a time when providing a stable gun platform was considered the most important criterion for a fighting airplane. The importance of speed, rate of climb, ceiling and maneuverability—later to be recognized as among a fighter’s most essential assets—was not yet appreciated. Nevertheless, the F.B.5 was a start, and the sky would never be the same after the advent of the Gun Bus.

Although no originals survive, the Royal Air Force Museum at Hendon possesses a beautiful full-sized flying Vickers F.B.5 replica constructed in 1966. No. 11 Squadron, the world’s first fighter squadron, still exists in today’s RAF, and currently flies the Eurofighter Typhoon.

This article originally appeared in the January 2019 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!