In May 1901 writer Lewis Freeman was rafting down the Yellowstone River when a minor spill brought an end to his sport. At the time, according to his account in the July 1922 Sunset Magazine, he was working as a reporter in Livingston, Montana, playing baseball with the local team and rafting whenever he got the chance. The old town had long since seen its salad days. That evening as he strolled around town, Freeman was wearing the “only nether garment” he owned at the time—a pair of checkered knickers. Returning to his room after a late visit to a local saloon, he was startled by a gruff voice calling to him from the vicinity of a lamppost: “Short Pants! Oh, Short Pants—can’t you tell a lady where she lives?”

“Show me where the lady is, and I’ll try,” he replied.

“She’s me, Short Pants—Martha Canary—Martha Burke, better known as ‘Calamity Jane.’”

Calamity, arguably the most famous female character of the Wild West, had arrived from Cody, Wyo., that afternoon, rented a room over a saloon, gone out on the town and then promptly forgotten where she was staying. Freeman gathered some of the saloon crowd and began a search. Once they found Calamity’s room, a new problem surfaced—she had lost her key. Several of the men impatiently boosted her through a window before the impromptu search party broke up to look for their own beds.

“[When] I went to ask after Mrs. Burke’s health the following morning, I found her smoking a cigar and cooking breakfast,” Freeman wrote. “She insisted on sharing both, but I compromised on the ham and eggs. She had no recollection whatever of our meeting of the previous evening, yet greeted me as ‘Short Pants’ as readily as ever.

“Calamity Jane was about 55 years of age at this time and looked it….Her deeply lined, scowling, suntanned face and the mouth with its missing teeth might have belonged to a hag of 70….There was really nothing saturnine about her. Hers was the sunniest of souls, and the most generous. She was poor all her life from giving away things, and I have heard that her last illness was contracted in nursing some poor sot she found in the gutter.”

Freeman and Calamity Jane walked down a back stairway while continuing their conversation. That sunny May morning behind a Livingston saloon, Freeman asked for the story of the old woman’s “wonderful” life. “Sure, Pants,” she responded. “Just run down and rush a can of suds, and I’ll rattle off the whole layout for you.”

Returning with the “suds,” Freeman found Calamity sitting atop an empty beer keg. She began her story, but when interrupted with a question, she had to start over again. Suddenly, Freeman realized he was hearing the old 1896 spiel from her days as a living exhibit in a Milwaukee museum. Back then, for a dime, the famous Calamity Jane would rattle off her story for curious spectators. Freeman had grown up on a diet of dime novels by the likes of Ned Buntline and “Reckless Ralph,” and this interview was one of the glorious highlights of his life. But while Calamity reveled in her past days of fallen women, dance halls, soldiers, saloons and teamsters, a part of her must have realized that that life would ultimately destroy her. Mainly due to her drinking, her later years had truly become something of a calamity.

“It was just after payday, and she had been on a big drunk with the soldiers and had been having a hell of a time of it. When they put her in the post guardhouse, she was very drunk and near naked. Her name was Calamity Jane.”

Joseph Anderson

Martha, the future Calamity Jane, was born to Robert and Charlotte Canary in Princeton, Mo., in 1856. The family made the difficult journey to Montana Territory during the gold rush of the mid-1860s. The father failed at mining, and within a few years both parents had died. Apparently the children were put out for adoption, but Martha was of an independent nature. She soon struck out on her own. Her independent and boisterous personality soon led to the cribs, but brothel life was too confining. In 1874–75 she accompanied both George Custer and the Newton–Jenney Party into the Black Hills of Dakota Territory, but as a camp follower (read prostitute), not as a scout or guide as she later claimed. Most likely she was a camp follower again in 1876 when she “served with” General George Cook. She did what she had to do to survive on the hard and indifferent frontier.

Calamity had aged far beyond her years by the time she met Freeman in Livingston in May 1901, as the years of debauchery, alcoholism and malnutrition had caught up with her. A few months earlier she had turned up in Bozeman, where illness and her indigent condition landed her in the Gallatin County poorhouse. Newspapers nationwide picked up the story, prompting a flood of donations from Buffalo Bill Cody and other old-timers who had read of her plight. “Calamity is firmly on her feet again financially,” announced the April 5 Anaconda Standard. But after collecting enough donations to move out of the poorhouse, Calamity headed for the nearest saloon and resumed her old lifestyle, much to the disgust of her few real friends.

Following her binge in Livingston, she pushed on to Red Lodge, Mont. One day in Taft’s Saloon patrons found a seated Calamity unconscious, her swollen legs propped up on another chair. “There was no doubt about her being in a bad way,” a bystander later reported. “Both of her lower limbs and one foot were swollen twice their ordinary size, and her labored breathing seemed a hard struggle.” Bar patrons summoned the county physician, who gave her a cursory exam. When leaving, he shook his head, remarking she would not live another two hours.

The saloon crowd followed the sheriff outside and took up a collection for Calamity. When they had gathered a sizable amount, they returned to the saloon, but Jane was gone. A boy had last seen her limping toward the local train depot.

Martha’s colorful nickname, “Calamity Jane,” came much earlier, of course, and has been the subject of considerable speculation. Contemporaries and noted historians have dismissed her story of an Indian fight and rescue of a cavalry officer, who later dubbed her Calamity Jane. What makes more sense is a story recounted in the July 22, 1906, Washington Post from George Hoshier, a longtime friend of Jane’s who was a pallbearer at her funeral: “It was down in Cheyenne that I first knew Calamity, and that was in the fall of ’75….The way she got that name was this: She was always getting into trouble. If she hired a team from a livery stable, she was sure to have a smashup and have to pay damages when she got back. Why, if she’d got up on a fence rail, the durned thing would get up and buck. Calamity followed her everywhere, and so [James] Poulton [city editor of the Cheyenne Daily Sun] one day dubbed her ‘Calamity Jane,’ and the name stuck.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

In June 1876 young Joseph Anderson was in a wagon train headed for the Black Hills. A gold rush was underway at Deadwood Gulch, and the wagons were full of would-be miners, saloon owners, merchants and prostitutes. In his memoirs Anderson describes his journey to the goldfields in the wagon of Steve and Charley Utter. Behind them was the wagon of Wild Bill Hickok and a friend. At Fort Laramie they were told that as protection against the Indians, they must wait until at least 100 others joined them. Anderson relates an incident that occurred at the fort:

“While we were at Fort Laramie, the officer of the day asked us if we would take a young woman with us. It was just after payday, and she had been on a big drunk with the soldiers and had been having a hell of a time of it. When they put her in the post guardhouse, she was very drunk and near naked. Her name was Calamity Jane.”

Anderson’s account is corroborated by a contemporary article in The Cheyenne Daily Leader and an aside in Jane’s autobiography. Despite the legendary tales of Jane having been a scout for Custer and Crook and the killer of dozens of Indians and badmen, the real Calamity was as Anderson remembered her. It was pure chance she had traveled to Deadwood in the same wagon train as Wild Bill. Her fabricated frontier experiences were such that by the 1880s stage plays and dime novels, coupled with wildly exaggerated newspaper stories, had spread the legend of Calamity Jane across the country. In Deadwood, according to Anderson, Calamity quickly went to work as a prostitute.

Over the years Jane cohabited with a half-dozen or so men whom she referred to as “husbands.” Hickok was not among them. Reportedly only one of the relationships was legal. Her last paramour was a man named Dorsett, but this, too, was a brief affair.

In May 1901 the Pan-American Exposition opened in Buffalo, N.Y. The six-month gala is remembered today as the scene of U.S. President William McKinley’s assassination. Mostly forgotten is the fact the fairgrounds were lit by electric power generated from Niagara Falls, some 25 miles away. And, oh yes, Calamity Jane was there too. It happened this way.

That spring, as newsmen flooded the papers with tales of Jane’s indigence and illness in the Gallatin poorhouse, a writer in New York had a brainstorm. Josephine Winfield Brake had recently written a novel that was not selling as expected. As an exposition correspondent for a New York newspaper, she had rented a home in Buffalo, where she’d read newspaper accounts of Jane’s poorhouse experience. Brake dreamed up a scheme to put Calamity in a small hut on the exposition’s big midway. There, in the course of meeting curious tourists, Jane could pitch Brake’s novel, pocketing 10 cents herself for each sale. In theory it was a great idea, but it had one flaw: Calamity Jane herself.

From contemporary press accounts, Brake knew she was dealing with an alcoholic wreck at the end of her rope. No one knew for sure how old Jane was, but she obviously had only a few years left. Beyond the bookselling appearances, Brake would offer to care for Calamity for the rest of her life. Could a burnt-out alcoholic with no future but the gutter refuse that?

So, in June 1901 Brake headed west to find the dime novel heroine. If she had any illusions about her quest, they were quickly shattered in Montana. When inquiring where she might find Calamity Jane, Brake was directed down side streets and alleys into saloons and low dives of every description. Still she persevered and in mid-July finally found Calamity, recovering from a long drunk in a bordello on the banks of the Yellowstone near Livingston.

Worn out, sick and broke, Calamity was susceptible to anything. Brake explained the bookselling scheme, including her intent to care for Jane from then on, and the two were soon on an eastbound train. In a letter published in the July 20 Anaconda Standard, Brake was lyrical about the journey: “We arrived here [Buffalo] on Sunday morning. Calamity Jane has been all that I could ask her to be. When we reached our shady home, she again broke down and wept, saying: ‘Oh, how beautiful. I will never leave you.’ She is as happy as a human being will be and volunteered to drink no more whiskey. Someone on the train tried to persuade her to leave the train with them at Bismarck. I knew they would try it, but I intended the test to be made. She flatly refused. Her love and devotion for me are beyond description.”

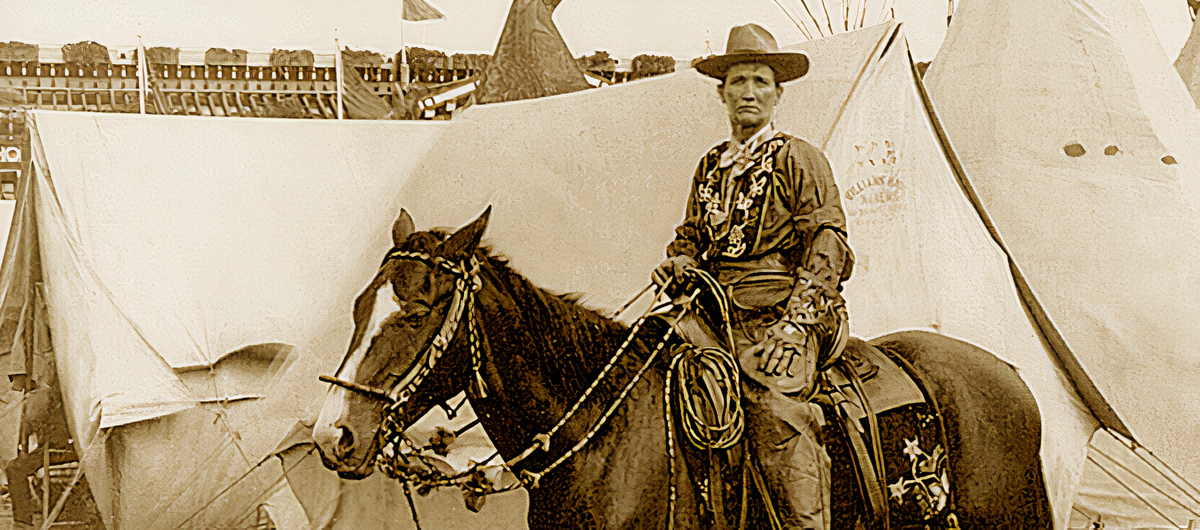

If all this sounds too good to be true, of course it was. Brake held a reception, introducing her protégé to local high society, then put Calamity to work. But after a brief period selling her sponsor’s book on the midway, Jane grew bored and dissatisfied. Brake was making $25 a week on the deal, while Jane merely received meals and a dime on each book. Her total weekly commissions, Jane later complained, added up to a mere 30 cents. About then another exhibitor made a bid for Calamity’s services. “Cummins’ Indian Congress” boasted a cast of Western Indians, including the famous Apache Geronimo. The old Westerner soon broke her contract with Brake and signed on with Frederick T. Cummins and his Indian Congress.

Jane seemed to have overlooked the fact Brake had offered to support her for life. Now that retirement plan was gone, but Calamity really didn’t care. Alcoholism was overwhelming her at this point. Day after day on the midway she posed for tourists on a horse in her buckskins. The boredom was crushing, but Calamity could soldier on if she could just get a drink. “On her first payday,” noted a Buffalo dispatch, “Jane passed out of the grounds. Across from the gates the door of a saloon stood invitingly open. Jane passed in.” On August 9 the Buffalo Evening News reported:

Alas, “Calamity Jane”—Mrs. Mattie Dorsett [her current “husband”], the original Calamity Jane of Wild West fame and who has been with the Indian Congress at the exposition during the last month, spent last night behind prison bars.

Patrolman Charles P. Gore, of the Austin Street Station, found the old woman on Amherst Street, near the exposition gate, last night. She was reeling from side to side and did not appear to know where she was. The woman had been drinking….She spent the night in the matron’s custody at the Pearl Street Station, was taken before Judge [Thomas] Rochford this morning and released on suspended sentence. Mrs. Dorsett said it was the first time she had been arrested.

When Buffalo Bill Cody and his Wild West arrived at the exposition for a performance, Jane burst into his tent and confronted the great scout. “They’ve got me buffaloed,” she told him. “I want to go back; there’s no place for me in the East. Stake me to a railroad ticket and the price of meals and send me home.” The great showman was touched and helped her out, as he had before. “I expect,” Cody later reflected, “she was no more tired of Buffalo than the Buffalo police were of her.”

After tanking up at the nearest tavern, Jane caught a train for Chicago, where she quickly drank up her food allowance from Cody. Appearing at a local dime museum, Calamity made enough for more drinks and a ticket for Minneapolis–St. Paul. In Iowa, the Waterloo Courier caught up to her at Fort Dodge in late September:

Some months ago she was induced to go to Buffalo and join a congress of Indian riders, at a salary of $25 a week, none of which she ever got. She finally got away from Buffalo and for the past few weeks had been slowly making her way west, by means of selling her photographs to those who would buy them. She feels sure, however, that when she once reaches Minneapolis, she can find friends there who will send her the rest of the way to her Montana home.

In Minneapolis she sought out the owners of the Palace Museum, where she had performed in 1895. They again hired Calamity on her promise to tell the public “of her wild life fighting Indians on the frontier.”

In November she appeared in Pierre, S.D., where she reportedly had friends. By then Jane was toting certain household goods that only added to her travel costs. In a December 10, 1953, letter to this author, old-timer Fred L. Fairchild recalled the last time he saw the frontier legend:

She was in the Northwestern freight office at Pierre, S.D., trying to convince the freight agent, Smith, to let her have her household goods, consisting of an old iron bedstead and springs, chairs and mattress, without paying the freight charges. She looked pretty frowsy, or disheveled. I did not stay to see how she succeeded with her pitch….She was seated on his knee with one hand on a shoulder and coaxing him, ‘for old times sake,’ to let her have the stuff. What I saw was not worth 5 bucks or less.

Fairchild also noted Calamity was still selling her photos for a living. When the weather took a nasty turn, Jane decided to winter in Pierre, reportedly toughing it out with a hard-luck family in a railroad boxcar. Her “friends” must have been of the fair-weather variety. It was a long, cold winter.

On March 12, 1902, Calamity Jane turned up in Aberdeen, S.D. “It is alleged,” wrote the local Daily News, “that while in town she remained very quiet and gave none of the exciting exhibitions of recklessness which are said to have characterized her visits to different towns…in years gone by. It is said that she remained quietly drinking and smoking in a saloon, but there she was not boisterous, and others in the place did not know who she was, with the exception of the proprietor.”

Within weeks Calamity was on the move again. Around mid-April she stopped over in the cow town of Oaks, N.D., while on her way to Jamestown. As reported in the Jamestown Daily Alert and picked up by the April 27 Anaconda Standard, she apparently felt the need to let off steam built up over the long winter:

She rather startled the men in one of the saloons, and one of them will not soon forget his experience. She was drinking with them and called them all up [to the bar]. The men thought they were pretty wise and thought they would josh the old lady. They were getting along nicely, when Calamity Jane pulled two guns and told them to dance. ‘You have had your fun, and now it’s my turn,’ she said. ‘You fellows don’t know as much as the calves out on my Montana ranch.’ The boys danced.

Another man who’d stayed clear of the bar chuckled at Calamity’s antics. Noticing him, she commanded him to also take a drink. “The command was made good with a wicked-looking gun,” recorded the Daily Alert, and the bystander quickly gulped down a glass of beer.

That same month Jane finally made it back to Montana. In Billings old friends clustered around her on the street and in the saloons as she regaled them with stories of her Eastern adventures and how Josephine Brake had betrayed her. “Calamity Jane arrived this morning from the East,” noted the April 16 Anaconda Standard. “She seemed greatly pleased to return to her old stamping grounds and vows that nothing can ever induce her to again go east to take advantage of fine homes offered her by philanthropic ladies, and she will be perfectly happy if allowed to remain in Montana until her death.”

But times had changed. The old-timers ranks had thinned. Too many younger people saw her only as a coarse and nasty old woman who drank in saloons with men and told wild tales of the past. For Calamity it was wonderful to be back in the West, but in her sober moments she realized that for her nothing had changed. Once again she was destitute and homeless, though at least she would die in the West.

We don’t know if Jane ever regretted giving up the home Josephine Brake had offered. In any case, it would never have worked out. On several occasions Brake had found liquor in her room, despite Calamity’s assertions she was through drinking. Sooner or later she would have been lured away by the demon that controlled her life.

Despite the abrupt ending of Calamity’s Buffalo adventure, Brake continued her efforts to obtain a government pension for Jane based on her tales of Indian fighting and scouting with the Army. Since she never did such things, of course, there would be no pension. But something had to be done. Calamity had nothing. She had lost her ranch years ago, although she liked to imply she still had it. “A move was recently started over our way to have Jane removed to the Park County poorhouse, and she flatly refused to go,” said a Butte man quoted in the June 23 Fort Wayne Evening Sentinel. “I do not blame her in the least…and I am in favor of collecting enough money to make Jane comfortable in her old age.”

Despite Calamity’s history of assisting the sick and poor during her lifetime, the obvious concern regarding any sort of pension was the very real fear it would only be subsidizing her drinking problem. Meanwhile, she moved on. Her arrival in Cheyenne was announced in the all-too-familiar manner via a dispatch from that Wyoming city. “Calamity Jane is on the rampage,” the Sioux Valley News reported on January 22, 1903. “Do you remember Calamity Jane? It is not the Calamity Jane of today, but she of, say, day before yesterday that you want to remember. She of today is old and poverty-stricken and wretched. The country has outgrown her, and her occupation is gone. When, to put it very plain and ugly, she gets drunk, she tries to shoot up the town in good old frontier style. But that sort of thing has been outgrown with a lot of other things…and so Jane finds herself in the lockup, where she is now…among the ‘plain drunks.’”

Calamity was in Sheridan, Wyo., for a time and then turned up at Belle Fourche in the Black Hills, working briefly as a laundress in a brothel. On August 1, 1903, she died in a hotel room in Terry, a few miles from Deadwood. Though just 47 years old, she looked more like 70. Conducting her Deadwood funeral were local pioneers, who heeded Calamity’s wish to be buried beside Wild Bill Hickok. The long-dead Hickok had no say in the matter. There were reports later, however, of rumblings in the cemetery, as of someone turning over in his grave.

Newspapers from Maine to Hawaii heralded Calamity’s death—most of them happy to repeat the many canards of her Indian-fighting service with the Army. The report in The Galveston Daily News was typical and reflected the changing times. Dominating the page above Jane’s obituary was an illustrated feature about “Langley’s flyer,” a model “aeroplane” and precursor to the Wright brothers’ first powered flight later that year. There was no longer room for a Calamity Jane in such a rapidly changing world.

Like other actual Army scouts, Captain Jack Crawford, who rode for Generals Wesley Merritt and George Crook, had no illusions about the legendary Calamity Jane he had known. The April 19, 1904, Anaconda Standard quoted him: “She never saw [military] service in any capacity under either General Crook or General Miles. She never saw a lynching and never was in an Indian fight. She was simply a notorious character, dissolute and devilish, but possessed a generous streak which made her popular.”

Teetotaler Crawford’s jaundiced appraisal was certainly mean-spirited, but it was also accurate. Most accounts of Calamity Jane’s life, including her own 1896 autobiography, are full of untruths and exaggerations. Her colorful legend lives on in discredited stories, books and films. If somewhere between Valhalla, heaven and hell there is such a thing as a big saloon in the sky, we can be sure Calamity Jane has found it.