Fifty years later people still ask the question about Alger Hiss: Was he or wasn’t he a Communist spy?

The headline blared from the front page of the New York Times on August 4, 1948: “RED ‘UNDERGROUND’ IN FEDERAL POSTS ALLEGED BY EDITOR,” it read. “IN NEW DEAL ERA. Ex-Communist Names Alger Hiss, Then In State Department.”

The ex-Communist was Whittaker Chambers, a rumpled, rotund editor at Time magazine. In testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) on August 3, Chambers said Hiss—the president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a former member of Franklin Roosevelt’s State Department—had been part of the United States Communist Party’s underground.

Chambers’ accusation reverberated like a bombshell in the Cold War atmosphere of 1948. “The case was the Rashomon drama of the Cold War,” said David Remnick in a profile of Hiss that he wrote for the Washington Post in 1986. “One’s interpretation of the evidence and characters involved became a litmus test of one’s politics, character, and loyalties. Sympathy with either Hiss or Chambers was more an article of faith than a determination of fact.” On the left was liberal New Dealism, represented by Hiss; on the right were conservative, anti-Roosevelt and Truman forces personified by Chambers.

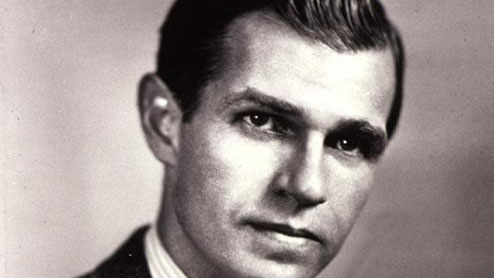

Depending on one’s politics, the idea that someone like Alger Hiss could be a Communist was either chilling or absurd. Erudite and patrician, Hiss had graduated from Johns Hopkins University and Harvard Law School. He had been a protégé of Felix Frankfurter (a future Supreme Court justice) and later a clerk for Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. In 1933, he joined Roosevelt’s administration and worked in several areas, including the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, the Nye Committee (which investigated the munitions industry), the Justice Department, and, starting in 1936, the State Department.

In the summer of 1944 he was a staff member at the Dumbarton Oaks Conference, which created the blueprint for the organization that became the United Nations. The next year Hiss traveled to Yalta as part of the American delegation for the meeting of Roosevelt, Joseph Stalin, and Winston Churchill. Later, he participated in the founding of the United Nations as temporary secretary general. In 1947, John Foster Dulles, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, asked Hiss to become that organization’s president.

Hiss’s accuser seemed to be his polar opposite. Whittaker Chambers was the product of a stormy and difficult marriage, and he grew up to be a loner. While at Columbia University, he showed literary talent but was forced to leave after writing a “blasphemous” play. He soon lost his job at the New York Public Library when he was accused of stealing books. Chambers joined the Communist Party in 1925, later claiming he thought that Communism would save a dying world. He worked briefly for the communist newspaper Daily Worker and then the New Masses, a communist literary monthly. In 1932 Chambers entered the communist underground and began gathering information for his Soviet bosses. A growing disenchantment with the Communist Party following news of the purge trials in Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union caused Chambers to leave the underground. In the late 1930s, he abandoned Communism and became a fervent Christian and anti-Communist. He started working at Time in 1939 and eventually became one of the magazine’s senior editors.

Chambers had accused Hiss of being a Communist before his 1948 HUAC appearance. Following the signing of the non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the USSR in August of 1939—a disillusioning event for American Communists, who believed the Soviet Union would remain a sworn enemy of Hitler’s regime—Chambers approached Assistant Secretary of State Adolf Berle and told him about “fellow travelers” in the government, including Hiss. Chambers recounted his Communist activities to the FBI in several interviews during the early 1940s, but little happened. The Soviet Union, after all, was then an ally in the war against Nazi Germany.

By the summer of 1948 the global picture had changed. As the Cold War chilled, Communist infiltration of the government—real or imagined—became a serious issue for both Republicans and Democrats. The Justice Department had been investigating Communist infiltration since 1947, but its grand jury had not returned any indictments. Republicans, eager to gain control of the White House in the fall election, had been bashing the Democrats for being “soft on communism.”

On Capitol Hill, HUAC, dominated by Republicans and conservative Democrats, was looking into possible Communist penetration of the Roosevelt and Truman administrations. Committee members, particularly an ambitious freshman congressman from California named Richard Nixon, knew what was at stake. HUAC was a controversial body under fire for its heavy-handed tactics. If Chambers’ story proved false, HUAC’s reputation would suffer a potentially fatal blow.

Hiss learned about Chambers’ testimony from newspaper reporters and immediately demanded an opportunity to respond. On August 5 he appeared before the committee and read from a prepared statement. “I am not and have never been a member of the Communist Party,” he said. Hiss also denied knowing Whittaker Chambers. “So far as I know, I have never laid eyes on him, and I should like the opportunity to do so.” Shown a picture of Chambers, Hiss responded: “If this is a picture of Mr. Chambers, he is not particularly unusual looking. He looks like a lot of people. I might even mistake him for the chairman of this committee.”

It appeared that Hiss had cleared his name. But Nixon—who had been told of suspicions about Hiss long before Chambers’ HUAC appearance—wasn’t satisfied. He argued that even if the committee could not prove Hiss was a Communist, it should investigate whether he ever knew Chambers. Nixon persuaded the other members to appoint him head of a subcommittee to investigate further.

At a session in New York City on August 7, Chambers provided more information. He said that Hiss’s wife, Priscilla, was also a Communist and that the Hisses knew him as “Carl,” one of the many names he used while working for the underground. He described the homes the Hisses occupied and the old Ford roadster and Plymouth they had owned. Hiss, Chambers said, insisted on donating the Ford for the use of the Communist Party despite the security risk.

Chambers’ information wasn’t completely accurate. He said the Hisses did not drink, but they did; he described Hiss as shorter than he actually was; he wrongly maintained that Hiss was deaf in one ear. However, he also provided information that indicated he knew them rather well. For instance, he reported that the Hisses were “amateur ornithologists” and had been much excited about observing a “prothonotary warbler” near the Potomac River.

On August 16 the committee summoned Hiss to appear in a secret session. This time Hiss conceded that a picture of Whittaker Chambers had “a certain familiarity,” but he was not prepared to identify the man without seeing him in person. He then described a man he had known in the 1930s and to whom he had briefly sublet his apartment. He hadn’t known him as “Carl,” but as “George Crosley.” Hiss described Crosley as a frumpish deadbeat with bad teeth who made ends meet by borrowing money and writing an occasional magazine article. When asked about the Ford, Hiss claimed he had given it to Crosley. Hiss also said Crosley had once given him an oriental rug in lieu of payment of rent. Chambers would later claim the rug was one of four he had given to “friends” of the Soviet people.

John McDowall, a Republican congressman from Pennsylvania, addressed Hiss. “Have you ever seen a prothonotary warbler?” he asked.

“I have, right here on the Potomac,” Hiss replied.

Nixon now wanted Chambers and Hiss to meet face to face. A meeting had been set up for August 25, but instead Nixon arranged to surprise Hiss with Chambers eight days ahead of schedule. In that tense and hostile meeting at New York City’s Commodore Hotel, Hiss asked Chambers to speak, looked at his teeth, and finally identified him as the man he knew as George Crosley. Hiss issued a challenge to his accuser. “I would like to invite Mr. Whittaker Chambers to make those same statements out of the presence of this committee without their being privileged for suit for libel. I challenge you to do it, and I hope you will do it damned quickly.”

The next confrontation was public, held on August 25 in a congressional hearing room in Washington. Public interest in the case gave it a circus atmosphere. The packed conference room was jammed with spectators, radio broadcasters, film cameramen and even hookups for live television. At this point Nixon and HUAC appeared openly hostile to Hiss. “You are a remarkable and agile young man, Mr. Hiss,” said one member of the committee after Hiss answered evasively about the fate of his Ford automobile.

Two days later Chambers appeared on the radio program “Meet the Press” and declared, “Alger Hiss was a Communist and may be now.” A month later Hiss filed suit for damages. “I welcome Alger Hiss’s daring suit,” Chambers said. “I do not minimize the ferocity or the ingenuity of the forces that are working through him.”

As Hiss’s suit prepared to go to trial, the case took a new, even more serious turn. It changed the main issue from whether Alger Hiss was a Communist to whether he was a spy.

In his earlier statements before HUAC, Chambers denied being involved with espionage. His contacts in Washington acted only to influence government policy, not to subvert it, he had said. It was the same story he later told the Justice Department grand jury. But when facing pretrial examinations for the libel suit, Chambers changed his story. He told his lawyers that he could produce evidence that Hiss had given him government materials. When he had broken with the Communist Party 10 years earlier, Chambers said, he had saved some documents in case he needed to protect himself from retribution. He sealed the documents in an envelope and gave them to his wife’s nephew, Nathan Levine. Levine hid the envelope in his parents’ Brooklyn home.

Retrieved from a dusty dumbwaiter shaft, the materials turned out to include 65 pages of typewritten copies of confidential documents (all except one from the State Department), four scraps of paper with Hiss’s handwritten notes on them, two strips of developed microfilm of State Department documents, three rolls of undeveloped microfilm, and several pages of handwritten notes. All dated from the early months of 1938. Chambers turned over most of the evidence but initially held the microfilm back in reserve. Fearing the federal grand jury would indict him for perjury, Chambers finally handed over the microfilm to HUAC. With a flourish of cloak-and-dagger dramatics, he had hidden it in a hollowed out pumpkin on his Maryland farm.

The so-called “pumpkin papers” ratcheted interest in the case up another level. Nixon immediately flew home from a vacation cruise in the Caribbean and posed for newspaper photographs showing him peering intently through a magnifying glass at the microfilm strips. The next day Nixon received a shock when an official at Eastman Kodak said the film stock dated from 1945—meaning Chambers had lied when he said he had hidden the film in 1938. Shaken, Nixon phoned Chambers and angrily demanded an explanation. It turned out that none was needed. The Eastman Kodak source called back and corrected himself. The film stock dated from 1937.

Hiss, who also testified before the grand jury, claimed the materials were either fakes or had come from someone else. The grand jury thought otherwise and on December 15, 1948, it indicted Hiss for perjury, accusing him of lying when he said he had never given State Department or other government documents to Chambers and that he had had no contact with Chambers after January 1, 1937. Espionage charges were not possible because the three-year statute of limitations had expired.

The trial began at the Federal Building on Foley Square in New York City, on May 31, 1949, and lasted for six weeks. The prosecution emphasized its “three solid witnesses”—a Woodstock typewriter once owned by Alger and Patricia Hiss, the typed copies, and the State Department originals—as “uncontradicted facts.” According to Chambers, Hiss took documents home from his office so his wife could type copies on the Woodstock. Hiss then returned the originals to his office and gave Chambers the copies. Chambers had the copies photographed for his Soviet handlers.

The typewriting would prove central to the case. The Hisses had once owned a Woodstock, and a comparison of the State Department copies with letters typed in the 1930s by the Hisses on their Woodstock indicated that they came from the same machine.

Hiss’s defense focused on his reputation—his character witnesses included a university president; several notable diplomats and judges, including Supreme Court Justices Felix Frankfurter and Stanley M. Reed; and Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois. In contrast, the defense portrayed Chambers as a psychopathic liar and “moral leper” who could have acquired the microfilmed documents through many different channels. As for the handwritten notes, someone could have stolen them from Hiss’s office or trash basket.

After a long search, the defense team tracked down the Woodstock typewriter. The Hisses had given it to a maid, Claudia Catlett. The defense hoped to prove that the Catletts received the typewriter sometime before the spring of 1938, but neither Catlett nor her sons could substantiate the giveaway date, weakening the defense considerably.

The first trial ended in a hung jury, with eight of the twelve jurors voting to convict Hiss. The Justice Department quickly announced it would seek another trial.

The second trial began on November 17, 1949, and lasted three weeks longer than the first one. This time the jury found Hiss guilty. He would serve 44 months in the federal penitentiary at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania.

The Cold War turned even colder in the years following Chambers’ first testimony and Hiss’s conviction, and continued to intensify after Hiss entered prison. China fell to the Communists in 1949, and the Soviet Union successfully tested an atomic bomb that same year. The following February, a little-known senator from Wisconsin, Joseph R. McCarthy, announced at a speech in West Virginia that he had a list of 205 “card-carrying members of the Communist Party” who were employed by the State Department. His sensational and unfounded charges launched a red-baiting career that would make his name forever synonymous with witch-hunting demagoguery. As historian Allen Weinstein later wrote, “Alger Hiss’s conviction gave McCarthy and his supporters the essential touch of credibility, making their charges of Communist involvement against other officials headline copy instead of back-page filler.”

Richard Nixon benefited as well. His role in the Hiss case helped him secure a senate seat over Helen Gahagan Douglas, a liberal Nixon labeled “the Pink Lady.” Two years later Nixon became Dwight D. Eisenhower’s vice president. Nixon would always consider the Hiss case a defining moment in his career and included it as the first of the “six crises” he described in his political memoir of the same name.

Chambers, who published his account of the case in Witness, a 799-page bestseller published in 1952, died in 1961 of a heart attack, a hero of the American right. In 1984, President Ronald Reagan awarded Chambers a posthumous Medal of Freedom. Four years later, the Reagan Administration designated Chambers’ Maryland “pumpkin farm” as a national historic landmark.

Hiss, who published In the Court of Public Opinion in 1957 to present his side of the story, never stopped fighting to clear his name. “I’ve spent a great deal of time on the issue of ‘Why me?’ ” Hiss told writer David Remnick in 1986. “I came to the conclusion that it’s largely accident, that I was well down the list of those who were selected in order to bring about a change in American politics.” Hiss said that he wasn’t the real target; he was merely a means “to break the hull of liberalism.”

Fortune began looking up for Hiss in 1972 when the Watergate scandal forced Nixon to resign the presidency. Nixon’s fall gave some credence to a wide spectrum of conspiracy theories involving fake typewriters, phony microfilm, and various collusions among the FBI, Nixon, HUAC, the CIA, the radical right, and the KGB. Hiss even theorized that Chambers, who had engaged in homosexual activity before his marriage, had a “deep attachment” to him, an unrequited passion that may have led Chambers to seek revenge. Hiss would return to that theme in a second book, Recollections of a Life, published in 1988.

Hiss’s prospects suffered a reverse in 1978 when Allen Weinstein published Perjury. Weinstein had set out to write an account sympathetic to Hiss. Using the Freedom of Information Act to gain access to previously classified materials from the State Department, Justice Department, and FBI, Weinstein finally concluded that Hiss was guilty. In Newsweek, columnist George Will wrote that with Weinstein’s book, “the myth of Hiss’s innocence suffers the death of a thousand cuts, delicate destruction by a scholar’s scalpel.”

Over the years, Hiss attempted to have his case appealed. In 1978, using the newly acquired government documents, he petitioned the Supreme Court for a third time, declaring gross unfairness (a writ of error – coram nobis). On October 11, 1983, the United States Supreme Court declined to hear his case.

Following the breakup of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, Hiss requested information from Soviet sources to clear his name. After extensive research, General Dimitri Volkogonov, head of the Russian military intelligence archives, declared, “Not a single document substantiates the allegation that Mr. Hiss collaborated with the intelligence services of the Soviet Union. You can tell Alger Hiss that the heavy weight should be lifted from his heart.” But questions from suspicious conservatives forced Volkogonov to admit he hadn’t searched the complex and confusing archives in great depth and that many of the files had been destroyed after Stalin’s death in 1953.

In 1993, a Hungarian historian, Maria Schmidt, divulged material from Communist Hungarian secret police files that seemed to suggest Hiss’s guilt. In 1949 Noel Field, an American suspected of being a Communist spy, had been imprisoned in Hungary as a suspected American spy. Under interrogation he had incriminated Hiss, in a confession Schmidt found in Field’s dossier. Field, however, had recanted after his release, and Hiss defenders considered the Hungarian documents to be tarnished evidence.

Another piece of evidence came to light in 1996 when the CIA and National Security Agency made public several thousand documents of decoded cables exchanged between Moscow and its American agents from 1939 to 1957. These materials were part of a secret intelligence project called “Venona.” A single document, dated March 30, 1945, referred to an agent code-named “Ales,” a State Department official who had flown from the Yalta Conference to Moscow. An anonymous footnote, dated more than 20 years later, suggested “Ales” was “probably Alger Hiss.” Hiss, one of only four men who had flown from Yalta to Moscow, issued a statement denying he was “Ales.” He went to Moscow merely to see the subway system, he said.

Alger Hiss died on November 15, 1996, at the age of 92. Was he one of the century’s greatest liars or one of its longest-suffering victims? “I know he was innocent,” says John Lowenthall, a friend and legal representative who made a documentary, “The Trials of Alger Hiss,” in 1978. “For most people it’s not a matter of fact, it’s a matter of ideology and emotion. Most of the people who take the stand that Hiss was guilty built their careers on it.”

Yet while the preponderance of evidence does weigh heavily against Hiss, his unrelenting insistence of innocence will keep the door of doubt ever so slightly ajar. David Oshinsky wrote in the Chronicle of Higher Education that the question of Hiss’s guilt or innocence has become, “like the case itself, part of our history. For intellectuals, left and right, it still taps the deepest personal values and political beliefs, raising questions about liberalism’s romance with Communism, and conservatism’s assault on civil liberties, years after the Cold War ended.”

A half-century after it started, the Hiss case remains a political dividing line.

James T. Gay is a professor of Hhistory at State University of West Georgia in Carrollton. This article was published in the May/June 1998 issue of American History. Subscribe here.