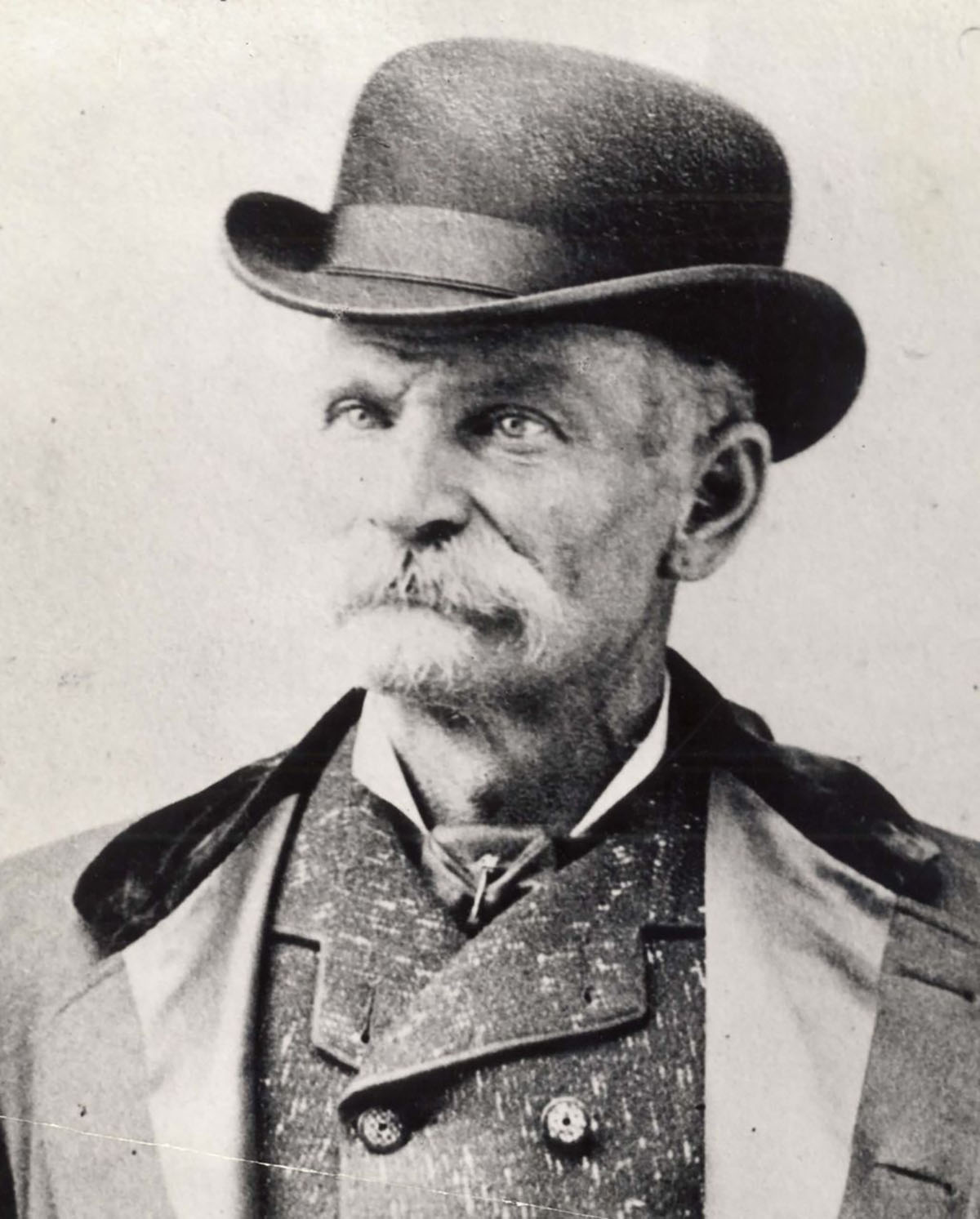

Charles E. Boles lived and looked the part of a Gilded Age dude, ” a gentleman who had made a fortune and was enjoying it.” But his fragile prosperity bubble was about to burst. One day in 1883, sporting a new derby hat, diamond stick-pin, diamond ring, and a gold watch, Boles twirled his walking stick and stepped out the door of San Francisco’s Webb House hotel into the waiting arms of his laundryman. This was an ominous sign.

Standing beside the man who took care of Mr. Boles’s dirty linen was Harry Morse, a detective for Wells Fargo & Co., who wanted to meet the aging peacock the launderer knew as Charles Bolton. So did his superiors. For weeks they had gone to every other wash house in northern California trying to identify a handkerchief with the laundry mark F.X.O.7. It had been found knotted around some buckshot at the scene of highwayman Black Bart’s latest escapade, the repeat robbery of a Wells Fargo stagecoach near Copperopolis, California.

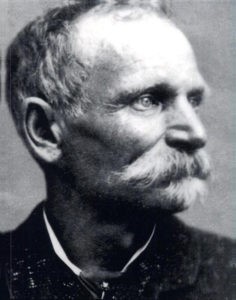

Morse and his boss, Chief of Detectives James B. Hume, believed in the office motto “Wells Fargo never forgets,” especially as it applied to the Black Bart case. For some reason this stage-stopping professional had selected their firm as the exclusive outlet for his business and, since July 26, 1875, had robbed at least 28 of their coaches.

None of the affairs had been as embarrassing as the first. On that day, on a steep grade outside Copperopolis, a man in a full-length duster, wearing rags bound around his feet and a sack over his head, stepped in front of a Wells Fargo coach as it labored uphill. Staring calmly at the driver through holes cut in his mask, the man on the road leveled a menacing shotgun at him and called out “throw down the box.” Coachman John Shine complied.

What happened next varies according to witnesses and legend, but supposedly, the bandit next said: “If he dares shoot, give him a volley.” At that, Shine looked to the roadside and, seeing several gun barrels aimed at him from the brush, decided to cooperate. He remained seated and, still under the guns of the robber’s gang, coolly observed Black Bart’s method of operation, one the highwayman would almost never vary.

Keeping the shotgun trained on the driver, the man in the duster produced a hatchet, chopped open the wooden lid of the iron-banded strong-box, and began stuffing bags of coin and cash into his pockets. Then he stepped aside and gestured for the stage to drive on.

Shine had driven his coach a short distance over the hill when he decided to pull up his team and go back for the smashed strong-box; it could be useful as evidence. Returning boldly to the robbery scene, he walked up to where the box lay, then stopped, stunned. The gang’s weapons were still trained on him. After imploring the gunmen to show mercy, Shine waited for flying lead or a reply. When neither came, he timidly approached the bushes, but he confronted no one. There was no gang, there were no guns, just straight, tapered sticks arranged to look like a deadly firing line.

The phantom gang feature was dropped from the nervy bandit’s repertoire after the first hold-up. But for all the rest of his robberies during the next eight years of his career, Black Bart’s simple method remained the same, with two exceptions. These variations, however, gave a clue to the sack-covered man’s personality. Following his third outing against the minions of Wells Fargo—the August 3, 1877 robbery of the Russian River stage near Duncan Mills, California—he left a poem in what remained of the violated strong-box that read: “I’ve labored long and hard for bread, for honor and for riches, but on my corns too long you’ve tred, you fine haire sons of bitches.”

Flaunting the reputation of Wells Fargo’s respected and feared company detectives was not enough for this increasingly expert professional. He had to sign the verse, pun in cheek, “Black Bart the Po8.”

Detective James Hume was not amused by any of this. And while the public took the “Po8” to its heart and circulated stories and rumors that made the truth difficult to ascertain, the lawman set about clawing clues out of the robbery areas. His quarry left no hoof prints behind and was known to have a deep, pleasant speaking voice. His hold-ups had no timing pattern, coming after long intervals or sometimes within a day of each other. And he had never fired his vicious-looking shotgun. The only consistent feature in the robberies, other than his method and his disguise, was that they were all committed in northern California.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Noted in the United States as a pioneer in scientific detection, Hume had made strides in the study of ballistics, was a stickler for detailed dissection of modus operandi, and had used the “mug shot” system for criminal identification for many years. But all his expertise in the refined arts of police work was useless in pursuing the man in the long duster. So Hume had to fall back on a detective’s first line of information gathering, footwork. Instead of pounding city pavements, he trooped up and down northern California hills talking to farmers, examining crime scenes, and measuring distances. By late 1882, this footwork paid off, giving Hume a detailed but surprising picture of Black Bart and the way he carried out his work.

Stage robbery was traditionally a younger man’s line, but to the 55-year-old’s amazement, Bart was a man close to his own age, perhaps older. Robbery area residents all reported seeing or meeting a gray-haired and magnificently mustachioed fellow who they assumed to be a migrant farm laborer. An excellent dinner companion and storyteller, “people invariably liked him.” He most often wore a derby, carried a bundle wrapped in a blanket, had boots slit open at the sides to relieve pressure on his corns, and was usually seen walking along at a brisk pace. If this character was the one Hume wanted, he would, in fact, be a tremendous hiker, having once robbed two different coaches thirty miles apart in a 24-hour period.

Within months of having pieced together this composite of the suspect’s appearance, Hume got a break. Bart struck again, on the same steep hill where he had committed his first hold-up. But this time he was forced to run. As driver Reason McConnell approached the grade, he dropped off a friend, Jimmy Rolleri, who wanted to do some hunting in the area. Pressing on up the hill, the coach was stopped by the man in the sack mask. Calling out “throw down the box” and whipping out his hatchet, the bandit prepared to go to work in his practiced manner when Rolleri broke through the same bushes where Bart had once posed his “gang.”

Black Bart never fired his shotgun. High-stepping through the roadside bushes, he clutched a bag containing $4,800 in gold coin and kept moving. McConnell snatched Rolleri’s rifle from him, shot at the bobbing target and missed. Rolleri had a try at it and was successful. Hit, Bart stumbled and fell.

Whooping and running, the driver and his friend thrashed into the undergrowth looking for the robber’s body only to find none. They were confounded. It would still be several weeks before the outlaw would have to face arrest.

In the 50 months he sat in San Quentin prison, Charles Boles must have had some time to mull over the way he had been apprehended. And in thinking it over, his final escape must have brought him satisfaction. For although McConnell and Rolleri had looked a long time for his carcass, they found only a derby, a straight razor, binoculars, and some buckshot wrapped in a handkerchief. Bart’s wound had been slight, allowing him to keep scrambling faster than was expected of a man his age.

During his years of larcenous mischief, Boles garnered—excluding some jewelry and petty cash picked from passengers—a mere $18,000 from Wells Fargo. But in 1883 that was a princely sum that could keep him in the just-short-of-elaborate style he preferred. He posed as Charles Bolton, a successful mining man; lived in comfortable San Francisco hotel suites; traveled frequently to Southern California for pleasure; wore fine clothing; and husbanded a nascent interest in poetry. However, the Southern California forays were often a sham, opportunities for Boles to ply perhaps the only trade he had ever followed with consistency.

Detectives Hume and Morse were not surprised when Boles first denied he had any connection with the stage robberies, declaring defensively, “I am a gentleman.” In fact, Morse admitted that Boles “looked anything but a robber.” More questioning, however, brought about a confession and Boles’s real background as a Midwesterner, a Civil War veteran, and a man who deserted his wife and children to come west and seek a fortune. But they were taken aback by what he had to say about the buckshot wrapped in the laundry-marked linen. In eight years of outstanding highwaymanship, Black Bart may have never loaded his shotgun.

Though he lived well during his robbery career, Boles had set aside a good deal of his booty and was able to return it to Wells Fargo when he was captured. This, and the fact that he had never harmed anyone in the course of a robbery, brought him the opportunity to plead guilty to one count of armed robbery and take a six-year sentence in the state penitentiary.

In consideration of his age—somewhere around 60—Boles was released from prison in 1887, before completing his sentence. In the four years and sixty days of his incarceration, his reputation had grown, and he emerged from San Quentin possibly more famous than when he first went in.

During his years in jail, he had been described in newspapers and dime novels as being everything from a poor school teacher to a starving poet. On his release, reporters rushed him, eager for the “true story.” Soon their questions became routine. When one reporter asked the old bandit if he would continue trying his hand at poetry, Boles replied, “Young man, didn’t you just hear me say I will commit no more crimes?”

Black Bart’s end is more in keeping with the way the romantics of his day would have had it. He disappeared. Although some reported he died in New York City in 1917, others preferred to believe that the poet bandit had gone to the wilds of Montana, or was it Nevada, game for another try at making a fortune.

This article was featured in American History magazine. For more stories, subscribe here.