Rhode Island Governor William Sprague stared into the empty grave with a mixture of shock and horror. Where was the body? The governor and his accompanying party had departed Washington City that March 19, 1862, morning for the old Bull Run battlefield, with the intent of retrieving the bodies of several 2nd Rhode Island officers left behind the previous summer after the Civil War’s first major fight.

When they arrived, however, the remains of Major Sullivan Ballou of the 2nd Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry were nowhere to be found. Upon further investigation, Sprague discovered that Ballou’s remains had been exhumed and desecrated by Confederate soldiers that winter. The morbid incident launched a congressional investigation and remains a controversy shrouded in mystery.

Sullivan Ballou has become famous in Civil War lore for the poignant letter he reportedly wrote to his wife, Sarah, a few days before he was mortally wounded. The missive was celebrated in Ken Burns’ watershed PBS Civil War series and is the focal point of dozens of Web sites, though what happened to his body after he died is seldom mentioned.

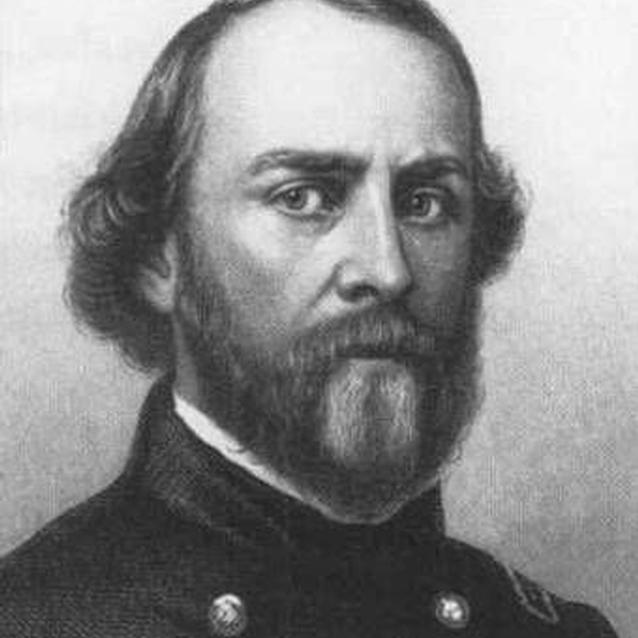

Ballou was the product of a distinguished Huguenot family from Smithfield, R.I. He was born on March 28, 1829, the son of Hiram and Emeline (Bowen) Ballou. He received his formal education at the Phillips Academy of Andover, Mass., and Brown University in Providence. After graduating from Brown, Ballou taught elocution at the National Law School in Ballston, N.Y.

While there, he also studied law and was admitted to the bar of his native state in 1853. He served as clerk of the Rhode Island House of Representatives for three years and in 1857 became a member of the House and was unanimously chosen speaker.

Ballou, like many Northerners disaffected with the Whig and Democratic parties, joined the new Republican Party when it was formed in the late 1850s. Through that affiliation, he soon became closely acquainted with Governor Sprague, a wealthy mill owner who became Rhode Island’s governor in 1860 at the tender age of 29, the youngest state executive in the United States.

After Civil War hostilities opened with the April 1861 bombardment of Fort Sumter, Rhode Island began to raise regiments for Federal service. On June 5, the 2nd Rhode Island was mustered into service in Providence and John Slocum was appointed its colonel, formerly having served as the major of the 1st Rhode Island. Due to his close ties to Governor Sprague, Ballou received a commission as major of the regiment.

The unit was soon sent to Washington, arriving in the capital on June 22. The 2nd was incorporated into Colonel Ambrose Burnside’s brigade, and by late July it was one of the dozens of green regiments moving out of the capital as part of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s army, headed for the Confederate lines along Bull Run.

McDowell’s plan of attack was for a portion of his army to demonstrate in the Rebel front, while the main Union attack column swung far to the right, using narrow paths through woods and fields, crossed Bull Run and Catharpin Run at Sudley Ford and then moved around behind the Southern left flank. Burnside’s brigade was combined with that of Colonel Andrew Porter to create a small division led by Colonel David Hunter that was selected to be in the van of the flanking movement. On June 21, Burnside’s soldiers led the way, with the 2nd first in line followed by the 1st Rhode Island. In a reflection of early war naiveté, Governor Sprague accompanied the regiments, riding on a white horse beside Burnside and determined not to miss their moment of glory.

The march was onerous for the Yankees. The Confederates had felled trees to block the road, which in many places was just a simple woods path that became chock-full of tired, sweating bluecoats. ‘What a toilsome march it was through the wood!’ recalled the 2nd’s chaplain, Augustus Woodbury.

Finally, around 9 a.m., well behind schedule, Burnside’s regiments splashed across both streams and headed south on the Manassas-Sudley Road — but not before the men took up even more time as they slaked their thirst in the muddy waters of the fords. Five companies of the 2nd heralded the advance, spread out as skirmishers on both sides of the road. To the left of the thoroughfare the land rose to form high ground, locally called Matthews Hill, as the Matthews house stood on its slopes. While the skirmishers cautiously moved toward the summit, they received their first hostile shots in the form of a volley delivered by elements of Brig. Gen. Nathan Evans’ South Carolina brigade.

Burnside quickly shifted his men to the left of the road to meet the threat, forming the balance of the 2nd in a battle line and ordering them up the hill behind the skirmishers. Sprague’s soldiers shucked off their packs and blankets and ran forward, rushing ‘wildly and impetuously’ and getting ‘rather mixed up,’ admitted Private Eben Gordon.

The disorganized but enthusiastic Rhode Islanders reached the crest of the hill recently abandoned by Evans’ outnumbered skirmish line. The Carolinians, however, had not given up the field; they had only fallen back down the southern slope of the hill, and they greeted the Rhode Islanders with a blast of hot lead. One private in the 2nd remembered it as a ‘perfect hail storm of bullets…scattering death and confusion everywhere.’

With his advance stalled, Burnside ordered up Captain William Reynolds’ artillery battery — also composed of Rhode Islanders and attached to the 2nd. The gunners moved to the summit of Matthews Hill and began blasting away while Burnside went in search of more help.

Colonel Slocum had been very active during the attack, and what he lacked in experience he made up for with courage and conspicuous leadership. He climbed atop the rail fence that ran across Matthews Hill and began waving his sword to encourage his men, but he was quickly felled with a grievous wound to the head. Privates Elisha Hunt Rhodes and Thomas Parker carried him off the field to the Matthews house, and then the colonel was evacuated by ambulance to the field hospital at Sudley Church, which was located near Sudley Ford.

Command of the regiment devolved upon Lt. Col. Frank Wheaton, and he helped Ballou to shift their line while Burnside worked to get the balance of his brigade — the 1st Rhode Island, 71st New York and 2nd New Hampshire — to come up. In order to better direct his men, Ballou rode his horse ‘Jennie’ in front of his regiment and turned his back to the Confederates. At that point, a 6-pounder solid shot, probably fired by a gun of the Lynchburg Artillery, tore off his right leg, killing his horse. The stricken major was then also carried to Sudley Church, where he joined the unconscious Slocum.

The 1st Rhode Island was the initial regiment to reach the line, arriving after the 2nd and Reynolds’ Battery had held off the Rebels for a half hour. Eventually, the rest of the brigade came up, and Burnside led it in a push that cleared the Rebels from the area north of the Warrenton Turnpike by about noon. The morning’s fight had gone to the Federals. That afternoon, however, the battle resumed with a markedly different complexion. A Confederate counterattack put the Union troops to flight back to Washington, and the fight ended as a Southern victory.

The 2nd Rhode Island took little part in the afternoon battle, remaining in reserve and licking its wounds with Burnside’s brigade. The regiment had suffered heavily: 93 of its men were killed, wounded and missing. Sprague survived the fight unharmed, though his horse was killed.

Ballou and Slocum, too badly wounded to move during the Federal retreat, were left behind in the care of army surgeons who amputated Ballou’s shattered leg. Both men died, Slocum on July 23 and Ballou on the 28th. They were buried side by side just yards from Sudley Church.

In early March 1862, word reached Washington that the Confederates were abandoning their lines around Manassas to move to protect Richmond from the Army of the Potomac’s advance up the peninsula. Union troops soon occupied the area, permitting Sprague and a band of 70 others to embark upon their body-recovery mission.

Privates Josiah W. Richardson, John Clark and Tristam Burgess of the 2nd assisted in the effort; they had also stayed behind at Sudley Church after the battle and had witnessed the burial of Major Ballou and Colonel Slocum. Troopers from the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry escorted the mission, and a surgeon, chaplain and two wagons filled with forage, rations and empty coffins rounded out the column.

The entourage made slow progress due to muddy roads and ever-present driving rains, and arrived at Cub Run on the eastern edge of the Bull Run battlefield on the afternoon of March 20. At that location, Captain Samuel James Smith of the 2nd Rhode Island had been killed during the retreat. As the evening grew dark, the party searched in vain along both sides of the creek without finding any sign of Smith’s grave.

Disappointed at the failure to find Smith’s resting place, the party pressed on to begin the search for other graves. Riding along the Warrenton Turnpike during stormy weather on the morning of March 21, the column arrived at Bull Run to discover that the stone bridge had been blown up by the withdrawing Confederates. Near its ruins the group examined a skeleton leaning against a tree, before they rode north and forded Bull Run and Catharpin Run.

They continued on to Sudley Church. Now abandoned and polluted with the remnants of war, the church stood with its door ajar, and several of the troopers stopped to investigate the structure. A few even rode their horses inside and up to the pulpit. Sprague instructed Private Richardson to lead the band of grave hunters to the spot near the churchyard where the Rhode Islanders were buried.

Richardson did so, pointing out two mounds that he claimed were where Colonel Slocum and Major Ballou had been buried. Soldiers began to dig amid the thickets of huckleberry bushes, the still graveyard echoing with the sound of shovels as the men went about their morose task.

Under the direction of Walter Coleman, Sprague’s secretary, the assemblage commenced with the exhumation of Slocum and Ballou. Just then a young black girl, full of curiosity, made her way from a nearby cabin to investigate. She approached the diggers and inquired if they were looking for ‘Kunnel Slogun’? If so, she said, they were too late and would not find him.

She went on to recite a chilling tale, claiming that a number of men from the 21st Georgia Regiment had robbed the grave several weeks prior. They had dug up Slocum, severed his head from his body and burned the mutilated corpse in an attempt the remove the flesh and procure the bones and skull as trophies. His coffin had been thrown into the creek, only to be later used in another burial.

Horrified, Sprague demanded to see evidence of such an atrocity. Followed by most of the anxious but skeptical group, he accompanied the girl as she led them to a nearby hollow, where they found a heap of charred embers along the bank of the creek. The ash was still gray, denoting that it was only a few weeks old. There they found what appeared to be bones. Upon closer inspection, Surgeon James B. Greeley of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry identified a human femur, vertebrae and portions of pelvic bones. Nearby they found a soiled blanket with large tufts of human hair folded inside.

As the troopers carefully collected the terrible evidence, one noticed a white object in the branches of a tree along the creek bank. A horse soldier waded into the stream and recovered two shirts, one a silk and the other a striped calico, both buttoned at the collar and unbuttoned at the sleeves. The circumstantial evidence seemed to concur with what the little girl had told Sprague, and it seemed even more plausible when Greeley did not locate a human skull or teeth with the other remains.

To add to an already confused, strange situation, Sprague insisted that he recognized both shirts as having belonged to Major Ballou — not to Slocum. Private Richardson, who had nursed Ballou in his last moments a week after the battle, concurred. With the identity of the beheaded body now in question, the anxious group rushed back to the gravesite. The troopers still had not found anything in the first grave. To probe for a solid object, Greeley suggested running a saber blade deeper into the ground. One was handed forward and thrust into the soft, mud-soaked soil. Driven almost to the hilt, it met with no resistance. The grave was empty.

The same tactic was applied to the other grave, but with different results, as a hard object was soon struck. Several cavalrymen began to dig, and they uncovered a rectangular box buried no more than 3 feet deep. The box was pulled from the grave, and the lid was pried off to reveal the body of 37-year-old John Slocum, rolled up in a blanket. Easily identifiable by his distinctive red, bushy mustache, Slocum’s remains were surprisingly intact. It now appeared that the missing body was that of Ballou.

To gather further evidence, Sprague, in company with his aide and Lt. Col. Willard Sayles of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry, went to the homes of nearby residents. In the process they met a 14-year-old boy who claimed to have witnessed the awful deed, and verified that it was soldiers from the 21st Georgia Infantry who had carried it out. The boy went on to reveal that the plot was premeditated, and that the Georgians had planned it for several days. He also claimed that the Rebels tried to burn the corpse, but had to prematurely dowse the fire because of the horrible stench it emitted. A farmer by the name of Newman confirmed the boy’s story, contending that no Virginian would have done such a thing and that those responsible were from a Georgia regiment.

Sprague also talked to a woman who had nursed the wounded at Sudley Church after the battle. She claimed that she had pleaded with the Georgians to leave the dead at peace. Unable to persuade them, she had saved a lock of hair cut from Ballou’s head, in the hopes that someday someone might come to claim the body. Colonel Coleman took the lock of hair, promising he would return it to Ballou’s wife.

The rationale for such a desecration did not come from the battle. The 8th Georgia Infantry was the only regiment from that state that may have come into contact with the 2nd Rhode Island, and the 21st Georgia did not arrive at Manassas until after the battle, staying in winter quarters in the neighborhood of Sudley Church.

Perhaps the men of the 21st saw their actions as a misguided attempt to revenge the 8th Georgia’s losses at the hand of the 2nd. While in search of Slocum they uncovered both graves — Slocum in a simple box and Ballou in a coffin. Thinking the commanding officer must be buried in the coffin, they inadvertently mutilated the body of Ballou — not Slocum.

As darkness began to set in, Governor Sprague suggested they continue with the original aim of the expedition and search for the body of Captain Levi Tower, another 2nd Rhode Island officer mortally wounded at the battle. By candlelight, Private Clark, who had witnessed Tower’s burial, led the way. In the side yard of the bullet-scarred Matthews house Clark located the mass grave in which Tower was buried. The evening had grown too dark, however, to begin digging, and the party elected to continue the next morning. Seventeen men crowded into the Matthews’ parlor for the night, the same room to which John Slocum had been carried following his mortal wounding. With saddles for pillows, the lucky 17 slept by the heat of the fireplace while the rest of the party remained outside, suffering through a drizzly night.

At first light, Sprague and Greeley ventured into a nearby field to investigate the skeletal remains of a horse, which Sprague supposedly recognized as one that had been shot out from under him during the battle. Meanwhile back at the house, the exhumation of Levi Tower was underway. The mass grave revealed eight bodies, including Tower’s. Strangely, all of the men were found buried face down and barefooted, together with an unexploded shell, considered a blatant sign of disrespect by all present.

As the Federals dug away, a growing number of irregularly clad men had begun to gather on a nearby ridge. Fearing an ambush by guerrillas, the officers elected to return to Washington. The corpses were loaded into the wagons. Slocum’s and Tower’s remains had been placed in pine coffins, each marked with the appropriate name and date of disinterment. Ballou’s casket was filled only with charred ash, bone, the blanket that contained his tufts of hair and the two recovered shirts. After collecting souvenirs from the area, the troopers mounted and the party departed Bull Run with a greater sense of the terrible realities of war.

On the afternoon of March 28, the bodies of Slocum, Ballou and Tower arrived in New York City. The 71st New York State Militia escorted the hearses through Manhattan and down Broadway to the Astor House, where the coffins lay in state. To watch the procession, onlookers crowded windows, balconies and the rooftop of Barnum’s Museum.

Four days later, on a gray and stormy March 31, the remains of the three soldiers were reburied in Providence. Business was suspended, streets were draped in mourning and flags flew at half-mast. A grand procession of some 34 military units made its way down to Swan Point Cemetery. There, volleys of musketry were delivered amid the clap of thunder and tolling of bells. The three sons of Rhode Island had finally been properly laid to rest.

Governor Sprague, outraged by what had happened to Ballou, addressed the U.S. Congress’ Committee on the Conduct of the War on April 1, 1862. He reported, in detail, the horrible findings of the expedition. The committee launched an official inquiry into the matter, with the chief aim of the investigation being to resolve ‘whether the Indian savages have been employed by the rebels, in their military service, against the Government of the United States, and how such warfare has been conducted by said savages.’ At some point, the theory had been introduced that somehow Indians in the employ of the Confederacy committed the deeds, reflecting white 19th-century Americans’ view of Indians as much as anything suggested by concrete evidence. Nothing came of that accusation, but the story was picked up and sensationalized by the Northern press, appearing in The New York Times and the Providence Daily Journal.

The congressional committee’s investigation unearthed further testimony of grave desecration. A local Manassas woman, Mrs. Pierce Butler, testified that she had witnessed several instances of unidentified Confederates exhuming bodies with the intention of boiling off the remaining skin and removing the bones as relics. Butler even claimed to have heard one soldier of New Orleans’ Washington Artillery boast as he carried off a dug-up skull that he intended to ‘drink a brandy punch out of it the day he was married.’ On April 30 the committee officially concluded that soldiers of the Confederate Army had indeed performed such actions after the First Battle of Bull Run.

The actual truth in the case may never be known, as it is possible that those interviewed by the government simply stated what they thought would keep them out of trouble. It is indisputable, however, that Ballou’s body was desecrated, and that Confederate soldiers likely did the deed hoping that they were actually abusing the corpse of a Union colonel. The 21st Georgia was singled out and blamed, though other regiments also camped in the vicinity and could have committed the act. If the Georgians did the deed, it would be a noticeable blemish on what was otherwise a long and commendable war record, as the regiment saw action in most of the Eastern theater’s battles after Bull Run.

The 2nd Rhode Island honored its dead commander when it constructed one of the forts that protected Washington and named it Fort Slocum. Today, the location is known as Fort Slocum Park, near Kansas Avenue in the northeast section of the District of Columbia. Present-day city dwellers often make their way to the former bastion. It is likely that few who visit the park know the history behind its name.

Many more people — or at least those interested in the Civil War — do know about Sullivan Ballou because of the famous letter attributed to him that has been reprinted numerous times. That the remains of the man who supposedly penned the sad missive were treated in such a crude manner after his death presents an unbelievable irony and symbolizes the tragedy and horror of any war.

| The Letter Sullivan Ballou died at age 32, leaving behind a wife, Sarah, two children and a letter written to his spouse that would make him famous. Interestingly, however, the letter was never mailed, but was instead supposedly discovered in Ballou’s trunk. Also perplexing is that of the five copies of the missive known to exist, none is in handwriting that matches Ballou’s penmanship. Both factors call into question the document’s authenticity. Regardless, the letter remains as a testament to the tragedy of the Civil War for thousands of soldiers and their families. E.C.J.

*******

July 14, 1861. My Very Dear Sarah, The indications are very strong that we shall move in a few days — perhaps tomorrow. Lest I should not be able to write again, I feel impelled to write a few lines that may fall under your eye when I shall be no more. Our movements may be of a few days duration and full of pleasure — and it may be one of severe conflict and death to me. Not my will, but thine, O God be done. If it is necessary that I should fall on the battle field for my Country, I am ready. I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage does not halt or falter. I know how strongly American Civilization now leans upon the triumph of the Government, and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution. And I am willing — perfectly willing — to lay down all my joys in this life to help maintain this Government and to pay that debt. But, my dear wife, when I know that with my own joys, I lay down nearly all of your’s, and replace them in this life with cares and sorrows, when after having eaten for long years the bitter fruits of orphanage myself, I must offer it as their only sustenance to my dear little children, is it weak or dishonorable, that while the banner of my forefathers floats calmly and proudly in the breeze, underneath my unbounded love for you, my darling wife and children should struggle in fierce, though useless contest with my love of Country. I cannot describe to you my feelings on this calm Summer Sabbath night, when two thousand men are sleeping around me, many of them enjoying perhaps the last sleep before that of death while I am suspicious that Death is creeping around me with his fatal dart, as I sit communing with God, my Country and thee. I have sought most closely and diligently and often in my heart for a wrong motive in thus hazarding the happiness of those I love, and I could find none. A pure love of my Country and of the principles I have so often advocated before the people — ‘the name of honor, that I love more than I fear death,’ has called upon me, and I have obeyed. Sarah my love for you is deathless, it seems to bind me with mighty cables, that nothing but Omnipotence could break; and yet my love of Country comes over me like a strong wind, and bears me irresistibly on with all those chains, to the battle field. The memories of all the blissful moments I have spent with you, come creeping over me, and I feel most gratified to God and you that I have enjoyed them so long. And how hard it is for me to give them up and burn to ashes the hopes of future years, when, God willing we might still have lived and loved together, and seen our boys grow up to honorable manhood around us. I have, I know, but few and small claims upon Divine Providence, but something whispers to me — perhaps it is the wafted prayer of my little Edgar, that I shall return to my loved ones unharmed. If I do not, my dear Sarah, never forget how much I love you, and when my last breath escapes me on the battle field, it will whisper your name. Forgive my many faults, and the many pains I have caused you. How thoughtless, how foolish I have often times been! How gladly would I wash out with my tears, every little spot upon your happiness, and struggle with all the misfortunes of this world to shield you, and my children from harm. But I cannot. I must watch you from the Spirit-land and hover near you, while you buffit the storm, with your precious little freight, and wait with sad patience, till we meet to part no more. But, O Sarah! if the dead can come back to this earth and flit unseen around those they loved, I shall always be near you; in the gladest days and the darkest nights, advised to your happiest scenes and gloomiest hours, always, always; and if there be a soft breeze upon your cheek, it shall be my breath, or the cool air cools your throbbing temple, it shall be my spirit passing by. Sarah do not mourn me dead; think I am gone and wait for thee, for we shall meet again. As for my little boys — they will grow up as I have done, and never know a father’s love and care. Little Willie is too young to remember me long — and my blue eyed Edgar will keep my frolics with him among the dimmest memories of his childhood. Sarah, I have unlimited confidence in your maternal care and your development of their characters, and feel that God will bless you in your holy work. Tell my two Mothers I call God’s blessings upon them new. O! Sarah I wait for you there; come to me, and lead thither my children. Sullivan |