Jackson, Johnston and conflicting interests

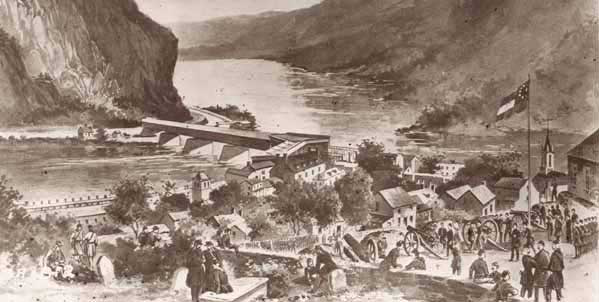

The fate of strategic Harpers Ferry hung on the leadership styles of two Southern commanders

Ten weeks before earning the sobriquet “Stonewall” on Henry Hill at the First Battle of Manassas, Thomas Jonathan Jackson was standing like a stone wall—along the Potomac.

Jackson’s intransigence was not directed against advancing Yankees, however, but at his own government. Virginia’s secession convention voted April 17, 1861, to leave the Union, and less than two weeks later, Old Dominion Governor John Letcher selected Jackson to command the strategic post of Harpers Ferry, at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers. The Virginians had seized the coveted United States armory at the Ferry within 24 hours of the vote. By the time Jackson arrived April 29, nearly 4,000 militiamen had concentrated there, headed by “corn stalk and feather bed” militia generals strutting about in glittering uniforms and offering whiskey to all comers as a display of goodwill and courtesy. “Nothing was serious yet,” quipped Henry Kyd Douglas, reporting for duty as a private with the Shepherdstown Hamtramck Guards. “Everything much like a joke.”

The former Virginia Military Institute professor discovered “things presented a most hopeless aspect” upon his arrival, and immediately began transforming Harpers Ferry into an army town. Drawing upon his experience as a West Pointer and Mexican War veteran, Jackson first deposed the militia generals and disposed of the whiskey. He then stripped independence from the individual militia companies and organized them into regiments, recruiting VMI graduates into many command positions. Within a week of Jackson’s arrival, the “pomp and circumstance of glorious war” had been replaced with seven hours of daily drill and enforcement of the strictest military code. “What a revolution three or four days had wrought,” observed the commander of the Staunton Artillery. “Perfect order reigned everywhere.”

Robert E. Lee was pleased. “[I] am gratified at the progress you have made in the organization of your command,” telegraphed the chief commander of Virginia’s burgeoning forces. But General Lee had another important assignment—removing the Harpers Ferry Armory machinery to Richmond. With the fledgling Confederacy plagued by a shortage of arms, and even less capable of weapons manufacturing, the capture of a federal armory was a godsend. The Virginia Secession Convention had instructed Lee, as a top priority, to move the valuable rifle- and musket-producing machinery from northern Virginia safely into the interior. Leeassigned the task to Jackson on April 27 in his first orders to his new subordinate. “It is desired that you expedite the transfer,” he said.

One week after his arrival, Jackson informed Lee that two-thirds of the machinery had been moved to nearby Winchester, awaiting further transfer. It was an extraordinary accomplishment, considering difficulties in dismantling the sensitive machines (and their water-powered gearing and shafting), along with transporting the tonnage to Richmond. Though alarmed to see their jobs moving south, many of the former U.S. government armorers assisted in taking apart the machinery, but not everyone was so accommodating. When Jackson learned a wagon shortage had developed because merchants were paying double the government rate for hauling, he seized the rolling stock. When Jackson discovered that transport of flour on the Winchester & Potomac Railroad commanded a higher price than conveyance of the machines, he promptly impressed the trains. Local citizens screamed about interference in their private businesses. Jackson reminded them they now were at war.

War, indeed, stared at Jackson from just 800 feet away. Only the width of the Potomac River separated the United States from the newly formed Confederate States of America. No other Southern commander was so near the enemy’s territory so early in the war. Aware of his tenuous circumstance, a resolute Jackson informed Lee, “My object is to put Harpers Ferry in the most defensible state possible.”

Jackson applied his artillery training to the study of the local topography. Three mountains loomed high over Harpers Ferry. The biggest—Maryland Heights—dwarfed its two neighbors, overshadowing the landscape from the Maryland shore of the Potomac. Jackson concluded that Maryland Heights was the key to defending Harpers Ferry.

“I have occupied the Virginia and Maryland Heights,” Jackson apprised Lee on May 6. “Whenever the emergency calls for it, I shall construct [fortifications] on Maryland Heights.” Jackson then added, “Thus far I have been deterred from doing so by a desire to avoid giving offense to [Maryland].”

Giving offense?

Credit Jackson for his political acuity. As a slave state, Maryland was a sister of the South. Baltimore was the South’s second largest port city, after New Orleans. The first effusion of blood in a Southern city occurred in Baltimore, one week after Fort Sumter, when city residents blocked and attacked the first Union infantry regiment (the 6th Massachusetts) en route to Washington. Maryland men daily streamed to Harpers Ferry to join the Rebels. Maryland, like Virginia, faced the option of secession. Yet Jackson knew Maryland had not yet removed its star from the spangled banner. Thus he must be judicious—and patient.

Jackson’s patience lasted 24 hours. He boldly informed Lee on May 7 that “I have finished reconnoitering the Maryland Heights, and have determined to fortify them at once, and hold them…be the cost what it may.” Be the cost what it may? Who had given Jackson the authority to establish the threshold of cost? Was a colonel about to determine the future of the Confederacy?

Jackson’s pendulum had swung from political pragmatism to the right of martial might. He subjugated political considerations and sister-state sensibilities to military judgment: “I am of the opinion that this place should be defended with the spirit which actuated the defenders of Thermopylae, and, if left to myself, such is my determination.”

The announcement mortified Lee. “In your preparation for the defense of your position,” he responded, “it is considered advisable not to intrude upon the soil of Maryland.” Intrude. Lee purposely selected the word to get Jackson’s attention—and to restore his political sensitivity. At that moment, Maryland was complaining bitterly about the Lincoln government’s “invasion” of its sovereign territory. If Jackson remained implanted on Maryland Heights, would Maryland not consider him—and by extension, the Confederacy—an intruder as well?

“I fear you may have been premature in occupying the heights of Maryland,” Lee rebuked, and reminded Jackson of his mission—“The true policy is to act on the defensive, and not invite an attack”—and then followed with a request (but not an order): “If not too late, you might withdraw until the proper time.”

What did Lee consider the proper time?

Maryland’s secession. Southerners expected it. Many Marylanders demanded it. Lincoln anticipated it. Following the bloody tumult in Baltimore, Maryland Governor Thomas Hicks sent the president a warning. “I feel it my duty,” he wired Lincoln on April 22, “to advise you that no more troops be ordered or allowed to pass through Maryland.” On the same day, Letcher ordered 1,000 Harpers Ferry weapons delivered to the Maryland militia commander in Baltimore, which were received there with “our profound and grateful sense of the friendly spirit in which you have considered our destitution.” Federal authorities—concerned that Washington could be surrounded by hostile states—countered quickly by seizing Annapolis and Baltimore, posting guards over Maryland’s railroads and harbors, interrupting communications and supplies between Baltimore and Harpers Ferry and continuing the flow of Northern regiments into the state.

Maryland felt insulted and injured by the North, and through the force of Yankee soldiers, isolated from the South. “The people are in arms, and determined to unite in the cause of the South,” declared Daniel Clarke, son-in-law of an ex-governor. In a note to Confederate Attorney General Judah P. Benjamin, he proclaimed, “It is thought the legislature will pass an ordinance of secession at once.”

Lee tracked Maryland’s drive for secession from his headquarters in Richmond. Nothing from the South could be permitted to upset the momentum or sentiment for the Confederacy. Then word arrived of Jackson’s unilateral occupation of Maryland Heights.

“Your intention to fortify the heights of Maryland may interrupt our friendly relations with that State,” Lee warned Jackson on May 10. “[W]e have no right to intrude on her soil, unless, under pressing necessity, for defense.” Lee’s secondary discretion came with stricture, however. “At all events, do not move until actually necessary and under stern necessity.”

Lee’s admonition arrived too late. An aggrieved property owner on Maryland Heights fired off a letter to Governor Hicks complaining that Jackson’s troops had destroyed “a large quantity of timber by fire,” and demanded that Maryland seek protection against losses incurred by the “invasion of our State.” This angry protest, in conjunction with additional charges that Jackson’s soldiers had forcibly entered private homes, seized personal property and insulted and threatened “unoffending citizens,” compelled Hicks to appoint a special “Commissioner to Virginia” to investigate the allegations. Hicks explained to Letcher that these “outrages” are liable to “provoke hostilities between your people and those who suffer from such unlawful acts.” Letcher responded immediately, assuring Hicks that Virginia desired to “cultivate amicable relations.” He guaranteed Jackson would “restrain all acts of violence and lawlessness,” and Virginia acted promptly to pay the cost of all property damages.

Virginia’s rapid response averted a crisis, but Jackson’s men remained on Maryland Heights. The savvy colonel occupied the mountain with Kentucky troops, believing soldiers from another state that, like Maryland, had not yet seceded might prove more palatable. As more Marylanders arrived to serve in the Confederate Army, Jackson posted more than 600 of them on Maryland Heights to eliminate the stigma of an occupation by foreign forces. Jackson did not respond to Lee’s call for a withdrawal, either in writing or in action. He chose, instead, to adopt Lee’s secondary instruction —“under pressing necessity, for defense”—as his principal mission.

Fortunately for Jackson, an ally soon arrived in the form of a former U.S. senator qualified to advise on political and legal issues. James M. Mason, recently resigned from Congress and, like Jackson, a resident of the Shenandoah Valley, conveniently appeared in Harpers Ferry in mid-May, where he spent two days “as a deeply interested, however unskilled, observer of military affairs in this quarter.” For the first time, a politician interceded on Jackson’s behalf in a military matter. It would not be the last.

In a lengthy May 15 missive to Lee written after spending the night at Jackson’s headquarters, Mason stated he had read in Southern newspapers that “Governor Letcher had some scruple or doubt about occupying the mountain heights in Maryland.” After correctly observing that “whichever power holds those heights commands the town of Harpers Ferry,” Mason turned from military analysis to legal jurisprudence. “I want to speak only of our right to fortify and hold those heights, whether Maryland protest or no.”

Mason argued that the occupation of Maryland by hostile Union forces gave Virginia the right also to station soldiers in that state, “so far as necessary for self-protection.” Mason also contended that Maryland remained one of the United States—“a power now foreign to Virginia, and in open and avowed hostility to us.” Occupying Maryland territory, therefore, was only occupying enemy territory. Mason concluded that placement of troops on Maryland soil was not an invasion because the “occupation is defensive and precautionary only, and not for aggression, and will cease as soon as the enemy withdraw.”

Lee responded six days later with an admission. “There is no doubt, under the circumstances, of our right to occupy these heights,” he conceded.

What changed Lee’s position?

Maryland’s secession effort had failed.

The Lincoln administration had moved so swiftly to secure Maryland through force of arms that it had become helpless in defense and hapless in secession. The Maryland General Assembly’s Committee on Federal Relations, releasing its findings on May 9, determined the war was “unconstitutional, repugnant to civilization and sound policy, [and] subversive to free institutions.” Maryland had words, but not enough warriors to expel the Northern occupiers. The committee’s final resolution asserted it was “inexpedient to call a convention or to take measures for immediate arming and organization of the militia.” Thus Maryland could take no part “directly or indirectly.”

With Maryland declaring official neutrality, Richmond authorities acknowledged the northern border of the Confederacy would not be the Mason-Dixon Line, but the Potomac River. Harpers Ferry now became the most exposed outpost in the South, and Maryland Heights its fortress—on a disputed border.

As the debate closed on the politics of Maryland Heights, Jackson accelerated his preparations for defense. Trees were axed and burned atop the crest, opening fields of fire. Troops erected a wooden stockade that stretched 200 feet across the narrow summit. Slaves performed some of the work. The Alexandria Gazette reported the “laboring force of Negroes upon Maryland Heights is daily increasing” and that “Colonel Jackson seems to think that the pick and shovel are great weapons of warfare.” A correspondent for the newspaper in Harrisonburg, Va., delighted at the activity. “Our heights are being fortified perfectly,” he exclaimed. “[I]n a few days Harpers Ferry will be a point which all creation cannot take—not only impossible, but impregnable. Let Abraham make the most of that.”

Then arrived Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, whose assessment was entirely different. “Considered as a position,” he concluded, “I regard Harpers Ferry as untenable.”

Confederate President Jefferson Davis had personally sent Johnston to Harpers Ferry. As the management of military affairs in Virginia moved to Confederate control, Davis considered Harpers Ferry “valuable because of its relation to Maryland and as the entrance to the Valley of Virginia.” Hoping for Maryland’s eventual secession, Davis believed Harpers Ferry offered a military post that could fan Southern sentiment and encourage revolt against the Union. And Davis recognized the Shenandoah Valley for “the agricultural resources of that fertile region,” and realized retaining Harpers Ferry could impede or even block a Union invasion route. Davis also appreciated Harpers Ferry’s association with northwestern Virginia, where hostility to secession prevailed. By maintaining a presence at the Ferry, the South controlled the strategic Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, which offered a rapid link to the mountainous western region of Virginia and the ability to respond to Union incursions.

Because of Harpers Ferry’s importance to the Confederacy, Davis wanted an experienced and ranking officer at the post. He chose Johnston—the highest-ranking officer (Quartermaster General) to resign from the U.S. Army. Johnston, a native Virginian, got the assignment from Davis at the original Confederate capital at Montgomery, Ala. He assumed command from Jackson on May 25.

Almost immediately, Johnston predicted doom. “This place cannot be held against an enemy who would venture to attack it,” Johnston told Lee. Excuses abounded. His men were undisciplined. He had only 12 to 15 rounds of ammunition per man. He did not have enough men—7,000 effectives present, but he needed double that number. He lacked percussion caps. His line of defense was too long. He could not guard the river fords. He could easily be turned on either flank. He was operating in the “heart of a disloyal population.” Coupled with these disadvantages were almost daily alarms of thousands of enemy soldiers approaching from Pennsylvania and Ohio. “Would it not be better for these troops to join one of our armies than be lost here?” Johnston asked Lee on May 31.

Lee was stunned. How the tone had changed! From “Thermopylae” to “untenable” with the change of a commander. “The difficulties which surround [Harpers Ferry] have been felt from the beginning of the occupation,” he responded June 1. “I am aware of the obstacles to its maintenance….Every effort has been made to remove them, and will be continued.” Lee immediately dispatched the 1st Tennessee Infantry, followed by two additional Georgia regiments. He did not yield a single sentence to Johnston’s reported deficiencies. “[O]ccupy your present point in force and carry out the plan of defense,” he said.

Johnston remained recalcitrant. Claiming ignorance due to “no instructions having been given to me,” he asked, “Do these troops constitute a garrison or a corps of observation?” If the former, Johnston claimed, he lacked the resources to defend the Ferry. If the latter, he lacked the resources to defend the Potomac line and ward off invasion. What should he do?

“The abandonment of Harpers Ferry will be depressing to the cause of the South,” Lee replied.

Johnston fired back: “Would not the loss of five or six thousand men be more so?”

Exasperated, Lee referred the dispute to a higher authority. “The importance of the subject has induced me to lay it before the President,” Lee wired Johnston on June 7. “He placed great value upon our retention of the command of the Shenandoah Valley and the position of Harpers Ferry.”

“Notwithstanding this determination on the part of the Executive,” Johnston declared, “I resolved not to continue to occupy the place.”

Subsequently, on June 14—armed with discretionary authority from Lee to leave if attacked, and reluctant permission from the Davis administration to retire “whenever the position of the enemy shall convince you that he is about to turn your position”—Johnston evacuated Harpers Ferry. His pretext was an intelligence report from Romney—nearly 60 miles west—of its seizure by the vanguard of George McClellan’s force from Ohio. Soon, Confederate authorities learned that only 500 Yankees on a one-day raid caused Johnston’s panic and precipitous abandonment of the Ferry.

Johnston’s rashness at Harpers Ferry generated a distrust that affected Confederate high command for the remainder of the war—presaging a sensitivity to criticism and a tendency to err on the side of caution. n

Dennis Frye is chief historian at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park and the author of several Civil War histories.