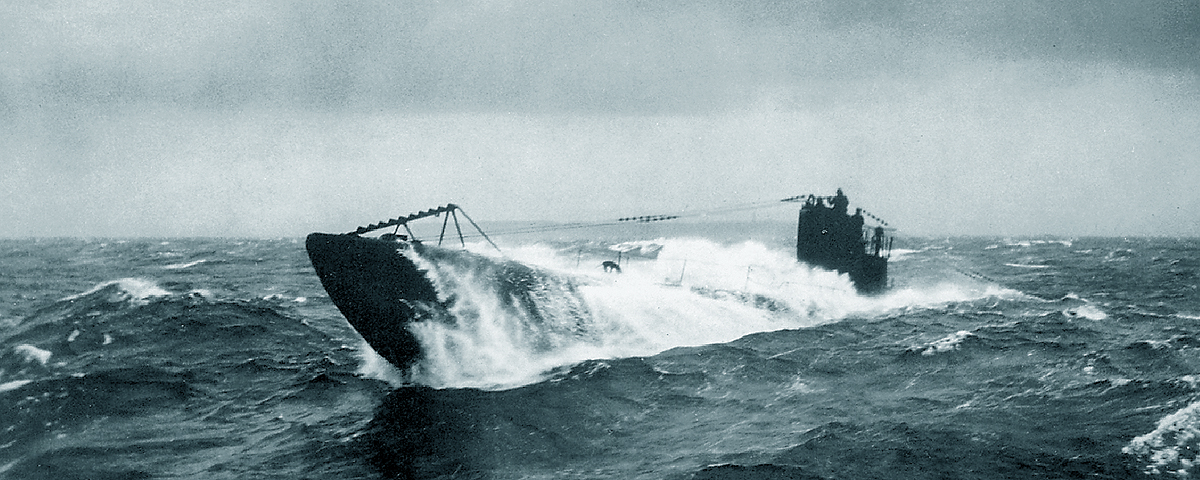

At 10 p.m. on the snowy night of Nov. 29, 1944, at the head of Frenchman Bay north of Mount Desert Island, Maine, the German submarine U-1230 slipped to the surface. At that late point in the war things were going badly for Germany. The Allies had landed in Normandy that June and had since been working their way across occupied Europe toward the “Fatherland.” Preparing to debark from U-1230 were two Nazi spies charged with a mission that could affect the outcome of the war and the very survival of the Third Reich—or so one of the agents later claimed.

The agents aboard the U-boat that cold November night could not have been more dissimilar. The senior of the pair, 34-year-old Erich Gimpel, was a German-born loyalist and experienced agent. His career had begun in the late 1930s in Lima, Peru, where, while working as a mining company radio operator, he reported on the movements of various countries’ ships and the nature of their cargos. After the United States entered the war in 1941, Gimpel returned to Germany, where he attended spy school in Hamburg and Berlin.

Gimpel learned tradecraft, including how to capture microdot photographs, build radio transmitters and communicate with invisible ink. He was trained in jujitsu and the use of firearms. “I was further trained,” he later wrote, “in smuggling, stealing, lying, cheating and similar arts.”

Assigned the code name Agent 146, Gimpel served briefly in Germany as a courier for military intelligence and then was sent to Schutzstaffel (SS) espionage schools in France and the Netherlands. It was at the latter he met his partner in the two-man team that would step ashore on the snowy coast of Maine. That agent’s name was William Curtis Colepaugh, and he was cut from entirely different cloth.

For one, Billy Colepaugh was an American. Eight years Gimpel’s junior, the former Boy Scout was raised by his widowed mother in Niantic, a historic village in the coastal town of East Lyme, Conn., and had seemed destined for a career in the U.S. Navy. Keenly interested in naval engineering, he attended prep school at Admiral Farragut Academy on the New Jersey shore and was accepted into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But he flunked out of MIT after one semester. By then the war in Europe had begun. In 1942 Colepaugh moved to Philadelphia, where he was arrested for draft evasion. The authorities allowed him to join the Navy as an alternative to prosecution.

Probably owing to the influence of his mother—Havel (née Schmidt) Colepaugh had been born aboard ship as her German parents immigrated to the United States—Billy harbored sympathy for Germany that bordered on the obsessive. During his stint at MIT he began cultivating relationships with various German officials stationed in Boston, numbering among his acquaintances the secretary to the German consul. Months before the United States entered the war, Colepaugh attended a Hitler birthday celebration at the consulate and entertained Boston-based Nazi officials in his home.

Colepaugh had done little to hide his loyalties. In 1943 he received a special-order discharge “for the good of the Navy and convenience of the government.” In fact, the FBI had already placed Colepaugh and his family under surveillance as possible Nazi sympathizers.

The agency was accurate in its suspicions, but not fast enough to keep Colepaugh from defecting to the enemy. In early January 1944 he signed on as a mess boy aboard MS Gripsholm, a Swedish ocean liner then under U.S. government charter as a repatriation and prisoner exchange vessel. Ironically, that exempted Colepaugh from military service. He had no intention of remaining aboard. Jumping ship in Lisbon, Portugal, he informed the German consul of his wish to join the army of the Reich and made his way to Berlin.

On meeting him, however, SS officials saw in Colepaugh a diamond in the rough—a homegrown American traitor who could be better used by Germany than simply as cannon fodder. As he spoke little German, Colepaugh was assigned to the espionage school in the Netherlands where he and Gimpel became acquainted.

After completing his SS training, Gimpel—who was fluent in Spanish and also spoke French and English—was sent to Spain, where he participated in several undercover missions, the last of which was a plot to assassinate U.S. Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower and blow up fortifications in British-held Gibraltar. The plot was discovered, however, and Gimpel returned to Germany.

He was next assigned to Operation Pelican, a mission to sabotage the Panama Canal and thus impede Allied maritime traffic. After much trial and error he lit on a plan. Two Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers with folding wings were to be loaded aboard U-boats and ferried to an island near the canal. There they would be reassembled, armed with high-explosive bombs and flown to their target, a vulnerable spillway. Just as the loaded U-boats were to leave Germany, however, planners called off the operation. An informer had compromised the mission.

Recalled to headquarters, Gimpel was given what would prove his last assignment. Code-named Unternehmen Elster (Operation Magpie), the mission was, as Gimpel put it in his 1957 memoirs, “Germany’s last desperate attempt at espionage during World War II.” There is no question of the real peril he faced. Two years earlier, in the wake of a failed German sabotage mission dubbed Operation Pastorius, U.S. authorities had executed six of the eight German infiltrators. But doubt remains over the true mission objective of Operation Magpie.

If Gimpel told the truth in his memoirs, his target was the Manhattan Project, the genesis of nuclear warfare

In Gimpel’s retelling, word had reached the German High Command of a secret weapon being developed by the United States, a device reportedly capable of leveling an entire city. The agent claimed German intelligence had ordered him to enter the United States undetected, find out whether such a weapon program existed and, if it did, determine whether Germany was the intended target. If Gimpel told the truth in his memoirs, his target was the Manhattan Project, the genesis of nuclear warfare.

Only there is no mention of such an objective in FBI documents or other documentary records regarding the mission. Indeed, verified sources paint a less glamorous, if still sinister, picture. Overseen by the SS, Magpie was conceived as an information-gathering operation, aimed at gleaning whatever technical engineering data—innovations in armaments, shipbuilding, aviation, rocket science, etc.—the agents could find in trade magazines or other publicly available sources. Gimpel was to relay any findings via coded telegraphy over a radio transmitter he would build. In an emergency he could report using prearranged mail drops.

Gimpel insisted on working with an American, to help gather intelligence and ensure he was up to date on the latest trends—movie gossip, baseball, dance steps, hair and clothing styles. He needed someone who, in his words, was “courageous, sensible and trustworthy” and would “work against his own country.” Gimpel chose all-American turncoat Billy Colepaugh.

As events soon proved, he could not have made a worse choice. For one, Colepaugh was, as Gimpel wryly put it, “one of the thirstiest and most accomplished drinkers I have ever met.” More important, though Colepaugh had bluffed his way into German service with bombastic rhetoric and vague notions of the glory of war, he was at heart a coward. “It was indeed my failure,” Gimpel reflected, “to assess the weakness in the character of my companion that led me almost to the hangman’s noose.” Again if his memoirs are to be believed, the senior agent did have enough foresight to leave Colepaugh in the dark about the “true” mission objective.

In late September 1944 the agents boarded U-1230 for the voyage to the United States. Each had been furnished a .32-caliber Colt semiautomatic pistol, a wristwatch and a small compass. They’d also been given false identification papers, a microdot device, invisible ink and the developing solution for any messages written in such ink. Gimpel carried radio parts. To sustain them over the planned two-year mission, the men had convinced superiors to provide them an outrageous $60,000 in U.S. currency—more than $800,000 in today’s dollars—and an onion-skin packet containing 99 small diamonds, to be pawned should the cash run out.

After 54 days at sea the U-boat slipped up Frenchman Bay to within a few hundred yards of shore. Shortly before midnight the two agents, dressed in suits and topcoats and each carrying a large suitcase, stepped into a dinghy to be rowed ashore. Colepaugh, Gimpel recalled, was “green with fear and shaking at the knees.”

The pair stepped ashore amid steadily falling snow and made their way to U.S. Route 1. As they trudged alongside the snow-covered road, two cars passed without stopping. The third proved to be an off-duty taxi. Explaining they had driven their car into a ditch, the two convinced the driver to take them the 35 miles to Bangor. From there they caught a train to Portland, then a connection to Boston. The next morning they caught another train to New York’s Grand Central Station and that afternoon checked into a hotel. They’d been on the move for most of the 40 hours since they stepped ashore, traveling unimpeded from a remote Maine cove to the heart of America’s most populous city.

Unknown to the two spies, their mission had nearly been scuttled before it began. The night they’d landed, a 17-year-old local Boy Scout named Harvard Hodgkins had been driving home from a school dance when he passed the hatless pair walking the other direction. A keen observer on the alert for wartime spies, the boy noticed that their tracks veered into the woods. Stopping the car, he followed the tracks down to the water’s edge. Returning home, Hodgkins told his father, who happened to be the local deputy sheriff. Deputy Hodgkins contacted the FBI, but nothing was done.

Several days later the FBI received word a U-boat had sunk a Canadian freighter off the Mount Desert Island. The submarine responsible was U-1230, whose captain had ignored orders not to molest Allied shipping during his sensitive mission. The belatedly alarmed FBI, fearing a U-boat operating so close to the coast might have landed enemy agents, sent its own agents from Boston to Maine to interview young Hodgkins. By then Gimpel and Colepaugh were hundreds of miles away.

On December 8 the spies secured an apartment on Manhattan’s East Side, where Gimpel set about assembling his radio and making plans to meet his contact. Colepaugh, meanwhile, became increasingly unmanageable, drinking, carousing and somehow managing to spend $1,500—more than half the average American’s annual salary. Three weeks after returning to his home country, he decided he’d had enough of life as a German secret agent.

On December 21 Gimpel returned to the apartment and was shocked to discover his partner had flown the coop, taking with him both suitcases—including all the money and the cache of diamonds—and leaving Gimpel with the clothes on his back and $300 in cash.

Assuming his partner would return to Grand Central Station, Gimpel followed up on his hunch and tracked down both suitcases in the baggage area. Explaining that he’d lost the claim tickets, he produced the keys and described the contents. The busy baggage clerk opened one of the bags to reveal dirty clothes and a camera (the money, radio parts and pistols were hidden beneath a false bottom), then waved him on. In his memoirs Gimpel wove a fanciful tale of running into a Peruvian acquaintance, who let the desperate agent use his apartment, where the spy soon engaged in a tryst with a beautiful young woman who also had a key to the apartment. It was a story straight out of Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels. The truth was he checked into another hotel and stashed the loot.

After pocketing $2,000 of “play money” and checking the bags at the station, Colepaugh, too, had checked into a hotel before embarking on a two-day carouse. On December 23 he looked up an old prep school classmate in Queens, who invited him to stay through Christmas. As the two washed up for a night on the town, Colepaugh confided he was in trouble and spilled the details of Operation Magpie. At first the friend, an honorably discharged U.S. Army veteran, dismissed his companion’s confession as the senseless ravings of a drunk. But when Colepaugh repeated the story in detail after sobering up, his friend counseled Colepaugh to turn himself in. On the evening of the 26th FBI agents arrived at the Queens home. After questioning the failed spy over several hours, they took Colepaugh into custody. Word of the arrest was immediately conveyed to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and, through him, President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The manhunt was on.

During questioning Colepaugh had described his former partner’s appearance and habits, including two vital pieces of information: Gimpel frequented a Times Square newsstand that sold Peruvian newspapers, and he carried his money in the inside breast pocket of his suit jacket. FBI agents staked out the newsstand, and on December 30 a man fitting Gimpel’s description walked up. Noting his foreign accent as he reached into his breast pocket to pay the clerk, they approached, questioned and arrested Agent 146, the most wanted man in America.

When Gimpel was arrested, one of the FBI agents took him aside and shared a candid observation: ‘You made only one mistake—you should have given Billy a shot between the eyes as soon as you landed’

After further interrogation the FBI turned over Gimpel and Colepaugh to military authorities, who confined the men at Fort Jay on Governors Island in New York Harbor. During the Civil War the fort had housed Confederate prisoners of war and served as the place of execution for at least two Rebel spies. It seemed likely the two Nazi agents would meet a similar fate.

Gimpel was thrown a lifeline. Agents from the Office of Strategic Services (a precursor of the CIA) offered to spare his neck in exchange for turning double agent, but he refused to betray his country. As loyal agents themselves, they likely respected Gimpel’s answer as much as they scorned Colepaugh as a traitor and deserter. Gimpel himself claimed that when he was arrested, one of the FBI agents took him aside and shared a candid observation: “You made only one mistake—you should have given Billy a shot between the eyes as soon as you landed.”

On Feb. 6, 1945, the German agents appeared before a military tribunal, charged with conspiracy to commit espionage, an offense for which the prescribed penalty was death. While Gimpel acted with forthrightness and reserve during the trial, Colepaugh sought to convince the court he had been acting all the while as a triple agent. He claimed to have traveled to Berlin simply to gather information on the Nazis, then returned with the intention of betraying Gimpel and Operation Magpie. The court dismissed that absurdity out of hand.

On Valentine’s Day, eight days after the trial began, the seven-man tribunal returned a guilty verdict. The defendants stood as the judge read their sentences: Both were to be hanged. Gimpel, long aware of the fate of captured spies, had anticipated such an outcome. But the prospect was one thing, the reality another. “You can think of death in a manly way when you’ve not been sentenced to death,” he recalled, “but heroics die a natural death of their own in the shadow of the scaffold. Before you meet your own death, the phrase ‘Death for the Fatherland’ dies.”

The execution date was set for April 15. For weeks Gimpel and Colepaugh nervously paced their cells, dreading their date with the gallows. One day a sergeant entered Gimpel’s cell, engaged him in a friendly chat, then departed. “Do you know who that was?” an amused guard asked with a laugh. “That was the hangman. He came to get an idea of your weight and measurements.”

Then, just three days before their scheduled date with the hangman, Roosevelt’s death triggered a four-week moratorium on executions as part of the national mourning period. Even more fortuitously for the condemned men, three weeks after that Germany surrendered. Never a fan of capital punishment, President Harry S. Truman reviewed the men’s cases and commuted their sentences to life imprisonment at hard labor. Both were sent to the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas.

Five years into Gimpel’s sentence guards found putty in his cell and on closer scrutiny found he had been sawing through the bars, though in the retelling Gimpel inflated the story into a jailbreak complete with sweeping spotlights and wailing sirens. The escape attempt bought him time in solitary confinement, followed by transfer to Alcatraz in San Francisco Bay, the notoriously escape-proof repository of such gangsters Al Capone, Alvin “Creepy” Karpis and George “Machine Gun” Kelly.

Gimpel spent five years there before being transferred to a state prison in Georgia. Shortly thereafter he was called before a judge, abruptly paroled and deported to West Germany. In his cabin on the ship home the 45-year-old former spy looked long and hard at his reflection. “I had grown old,” he recalled. “My hair was snow-white. My face was pale, the skin was taut and leathern. According to my birth certificate, I was 45, but the mirror told a different story.”

In 1960, after 15 years behind bars, William Colepaugh was paroled from Leavenworth. He settled in King of Prussia, Penn., where he married, started a business and devoted his spare hours to good works with the Boy Scouts and the local Rotary club. Colepaugh died in 2005 of complications from Alzheimer’s disease. Few acquaintances had known of his past.

After his release, Gimpel wrote a series of articles about his adventures as a secret agent. These were collated into book form as Spion für Deutschland (Spy for Germany), which was adapted into a German film and later printed in English under the title Agent 146.

Gimpel had always loved South America and eventually moved to Brazil. Twice in the early 1990s he traveled to Chicago as the guest of an American group of U-boat enthusiasts. Gimpel died in Sao Paulo in 2010. The 100-year-old had beaten the life-expectancy odds of his former profession, escaped the noose and survived prison. Yet living in the shadow of the gallows had left Gimpel a haunted man, as evinced by the closing lines of his memoirs: “I hate war. And I hate the job of a spy—I always shall.” MH

Frequent contributor Ron Soodalter is the author of Hanging Captain Gordon and The Slave Next Door. For further reading he recommends Agent 146: The True Story of a Nazi Spy in America, by Erich Gimpel, and A True Story of an American Nazi Spy: William Curtis Colepaugh, by Robert A. Miller.