As the Battle of Antietam unfolded, Major General Ambrose Burnside had good reason to wonder whether Army of the Potomac commander Major General George McClellan was as good a friend as he always had seemed. Up to the day of the battle, “Little Mac” had shown nothing but trust in the ability of his prewar chum. He had elevated Burnside from commanding the IX Corps to the oversight of the Left Wing of the army, the combined forces of the IX and V corps.

The campaign for both men had gone well—so far. With the advantage of finding General Robert E. Lee’s lost Special Orders No. 191 on September 13, McClellan had tracked down the Confederates and engaged them at South Mountain, forcing Lee into a defensive position along Antietam Creek near Sharpsburg, Md.

But then Little Mac had consumed 36 hours preparing to attack Lee’s heavily outnumbered Confederates on September 17, and the Rebels had been able to fend off the Union attacks throughout the early and midmorning hours. Burnside’s Left Wing was on the Federal left flank, and McClellan had wanted him to drive forward to Sharpsburg. Burnside began his attack around 10 a.m., but Antietam Creek and the steep bluffs on the western bank had prevented him from moving quickly.

McClellan began to grouse at Burnside for his perceived slowness. Burnside was puzzled; he had been the first Union commander to overtake Lee’s army in Maryland and the first to engage in battle at South Mountain, so Burnside and his staff considered McClellan’s behavior bizarre. It looked to them as though McClellan had grown jealous of his chief subordinate, or wished to use him as a scapegoat if something went wrong.

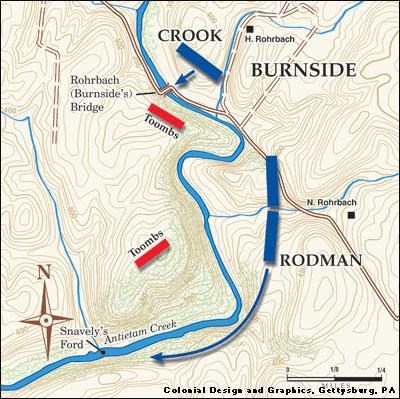

In Burnside’s sector Antietam Creek could be crossed on the stone triple-arched Rohrbach Bridge—immortalized after the battle as Burnside’s Bridge—or at Snavely’s Ford, the better part of a mile downstream. The day before the battle McClellan seemed to question Burnside’s competence when he sent the army’s chief engineer, Captain James Duane, to personally position Burnside’s divisions before the bridge and the ford. Duane performed this duty vicariously, though, through junior officers. They inadvertently placed General Isaac Rodman’s division in front of a reputed cattle ford, about midway between the bridge and Snavely’s Ford.

When Burnside received the order to attack, he threw one assault after another against the bridge, which turned out to be such a strong position that the Confederates held it for nearly three hours with a couple of depleted regiments. Rodman, meanwhile, moved forward to cross at the designated ford, only to find that it was too deep for infantry.

Earlier that year Captain Duane had published a manual for engineer troops that began with advice on river crossings. “A river with a moderate current may be forded by infantry when its depth does not exceed three feet,” read the third sentence of that manual, “and by cavalry and carriages when its depth is about four feet. The requisites for a good ford are, that the banks are low but not marshy, that the water obtains its greatest depth gradually, the current moderate, the stream not subject to freshets, and that the bottom is even, hard, and tenacious.”

These criteria applied to a routine crossing, uncomplicated by enemy resistance. Had Duane not known that Antietam Creek was too deep for infantry there, or that the banks were abrupt and the bottom treacherous, he ought at least to have been able to see from a great distance that the opposite shore rose to a steep bluff that infantry would have had to scale in the face of point-blank musketry—if the crossing could be made at all. Rodman soon deduced that he had been sent to the wrong place, so he started downstream for the rumored pedestrian ford near Farmer Snavely’s house.

Those who later criticized Burnside’s performance at Antietam first minimized the difficulty that the stream posed, then exaggerated the time it took him to put his troops across the creek. Bruce Catton started that trend in 1951, describing the creek as “insignificant” and “so shallow that a man could wade it in most places without wetting his belt buckle.” Although Catton was a marvelous literary stylist, he had not reconnoitered the creek despite his implied familiarity with it. Instead, he was echoing the words of Henry Kyd Douglas, who had served on the staff of “Stonewall” Jackson.

In 1899 Douglas had wondered in a manuscript memoir why Burnside had not simply swept across Antietam Creek. “Go and look at it,” Douglas urged, “and tell me if you don’t think Burnside and his corps might have executed a hop, skip, and jump and landed on the other side. One thing is certain, they might have waded it that day without wetting their waist belts in any place.” That criticism did not take root until after Douglas’ memoirs were finally published in 1940. Since Douglas took part in the battle and grew up only a few miles from the creek, however, scholars took him at his word without accepting his challenge to test the depth of the stream. The National Park Service even mounted a plaque on the eastern end of Burnside’s Bridge etched with Douglas’ snide comment.

If Antietam Creek was such an insignificant watercourse, one might wonder why local farmers had established any fords in that vicinity in the first place; after all, cattle hardly need as shallow a crossing as infantry. Lately, more careful historians have demonstrated that Douglas owned a penchant for hyperbole and invention, and his challenge to examine the creek turns out to have been pure bluff. Antietam Creek drains four counties in Pennsylvania and Maryland, and the spot where Burnside was asked to cross lay three miles short of the mouth, where it empties into the Potomac as a sizable stream. At times it rolls in a perfect torrent just downstream from Burnside’s Bridge, and only the most experienced whitewater raftsmen would dare test it then. Even with the sedimentary accumulation behind a postwar dam just downstream from the bridge, the creek lies too deep and muddy today, and its banks too steep, for the criteria of Captain Duane’s “good ford” for infantry.

A great deal of evidence confirms that it did serve as an effective military barrier in 1862. A 5-foot-6-inch Rhode Island lieutenant found the creek “breast deep” even at Snavely’s Ford, where he crossed, and a quarter of a century after the battle a New York Zouave who navigated the same ford remembered that it was at least waist deep.

Colonel George Crook’s brigade formed the upstream extremity of Burnside’s line, where the creek should theoretically have been even shallower than at the bridge. Crook thrashed about for more than two hours before he found one spot where a few men could wade the creek one at a time. The historian of Joseph Kershaw’s Confederate division acknowledged that the creek was “not fordable for some distance above the Potomac,” and concluded that it could be waded without difficulty only at the upstream end of Lee’s defensive line, well above Burnside’s front. Prior to the publication of Douglas’ book, the impassability of the creek was never questioned.

Catton’s repetition of Douglas’ groundless comment soon encouraged two more historians to assail Burnside’s Antietam performance. In a 1956 article for Civil War History, Martin Schenck accused Burnside of wasting five hours in carrying the bridge. Schenck founded his indictment on McClellan’s revised report, in which he claimed that he issued Burnside attack orders at 8 a.m.

“The report clearly states that the order was issued at 8 a.m.,” Schenck wrote, but he ignored McClellan’s first report, in which McClellan admitted that Burnside received no orders until about 10 a.m. It was only in 1863, as McClellan tried to improve his public image, that he asserted he had sent Burnside’s instructions two hours earlier. Burnside’s report, which Schenck did not consult, timed the arrival at 10. Brigadier General Jacob Cox, who was standing with Burnside at IX Corps headquarters, ultimately concluded that the order reached them near 10 a.m.

McClellan’s actual order, which Schenck also overlooked, is headed “9.10 a.m.” Allowing a couple of minutes for transcription, a few more minutes to assign the envelope to the courier and to explain the location of Burnside’s headquarters, and at least 15 minutes for that rider to gallop overland with it, Burnside would not have had it in his hands before 9:30. Any of the likely variations from that basic scenario, such as a wrong turn or a halt for directions, would have brought the delivery closer to 10. Certainly it must have been that time before the first troops moved against the bridge and the bogus ford, so the IX Corps actually consumed less than three hours carrying the creek, rather than five.

In his 1957 biography of McClellan, Warren Hassler reiterated the bogus 8 a.m. attack order and Douglas’ inaccurate jibe about the depth of the creek. Also relying on McClellan’s self-serving autobiography, McClellan’s Own Story, posthumously published in 1887, Hassler described the commanding general dispatching a second staff officer to Burnside by 9 a.m. with orders to carry the bridge “at the bayonet.” He also cited the highly suspect 1894 reminiscence of one William Biddle, who insisted that McClellan sent Colonel Thomas Key to IX Corps headquarters at noon with a third imperative order to take the bridge at all costs.

Burnside’s troops had made their way over both creek crossings by 1 p.m. Samuel Sturgis’ division, which took the bridge, had exhausted both its ammunition and its stamina, so Burnside had to move Oliver Willcox’s fresh division in to replace it. Before he could continue his assault into the village of Sharpsburg, Burnside also had to bring his artillery and ordnance over the Rohrbach Bridge. Finally, he had to realign Rodman’s isolated division with the troops who had negotiated the bridge. By then McClellan had allowed the fighting on the right to fizzle out, so Lee was able to attend to Burnside a little more effectively, turning firepower on him from other parts of the line. McClellan had infected his subordinates with the fantasy that Lee had 100,000 men on the field, so Burnside proceeded somewhat cautiously with his 13,000.

Ironically, it was Hassler who tried to revise the estimate of McClellan’s available troops downward and Lee’s upward—from a Union strength of more than 80,000 and a Confederate force of about 40,000 to some 69,000 for McClellan and more than 57,000 for Lee. That reduced McClellan’s advantage in numbers from 100 percent to about 20 percent, but when it came to assessing Burnside’s performance Hassler seemed happy to revert to the traditional story of overwhelming Union forces—at least on Burnside’s front.

Hassler characterized Burnside’s realignment of troops as “sitting down” on the job, surmising that this additional delay is what prompted McClellan to send “Captain Biddle” with an imaginary fourth and final directive to move forward. To bolster this message, Biddle ostensibly carried a signed order to relieve Burnside and replace him with another officer: That order was supposed to be handed over if Burnside lollygagged any further.

There Hassler hopelessly muddled Biddle’s tale, ascribing actions to Biddle that Biddle attributed to Colonel Key. Hassler also failed to question why no one else, including George McClellan, mentioned any order for Burnside’s removal during the 32 years that intervened between the battle and Biddle’s reminiscence. It seems fairly obvious that Biddle’s account was one of those inventive recollections that pollute the stream of Civil War history, and that he was obliged to leave his provocative accusation unpublished until after the deaths of all those who might have contradicted it. Giving Biddle’s rendition such conspicuous credence showed poor judgment, at best.

Although he also criticized Burnside for proceeding cautiously, Hassler blamed him completely for the surprise attack of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill’s Confederate division, which struck a green Connecticut regiment and caved in Burnside’s flank. Hill had driven his men mercilessly all the way from Harpers Ferry, and his was the sort of counterattack Burnside had been preparing against, but Hill came up from a quadrant that no one expected—largely because McClellan had neglected to provide for general reconnaissance. The cavalry would normally have monitored such enemy movements on the outer flanks, but McClellan was holding all his cavalry in reserve for a final grand charge in the Napoleonic tradition.

McClellan and his contemporary apologists spent the remainder of the 19th century building the case against Burnside with half-truths, sarcasm and outright lies. Similar prejudice among subordinate generals also played a significant part in Burnside’s disastrous tenure at the head of the Army of the Potomac, which seemed to lend substance to that image of ineptitude.

By blaming Burnside for numerous other lapses—including the failure to destroy the Confederate army at Antietam—his detractors created an impression of overall incompetence. Through a combination of sloppy research, amateur analysis and selective presentation, a few 20th-century historians lent that jaundiced image an undeserved air of corroboration.

William Marvel writes from New Hampshire, where he insists it snows until July and starts again in August. He is the author of Burnside and Mr. Lincoln Goes to War, among other Civil War titles.

This article by William Marvel was originally published in the September 2007 issue of America’s Civil War magazine.For more great articles be sure to subscribe to America’s Civil War magazine today!