The failings of a U.S. plan to turn the war over to the South Vietnamese were revealed on the battlefields of An Loc and Quanc Tri when rapport degenerated into rancor

Westminster, California, is home to the largest Vietnamese-American community in the United States. When the Republic of Vietnam collapsed on April 30, 1975, this city near Los Angeles became a haven for many escaping refugees. The residents of “Little Saigon,” who now number more than 35,000, raised funds and lobbied the city to allow construction of a large Vietnam War memorial. The sculpture, dedicated in 2003, features two large statues, a soldier of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and a U.S. soldier, standing together. To many, they symbolize the bonds between the American adviser and the ARVN commanders he assisted. However, during the latter stages of U.S. involvement in the war, the relationship memorialized in the California monument wasn’t always a close one.

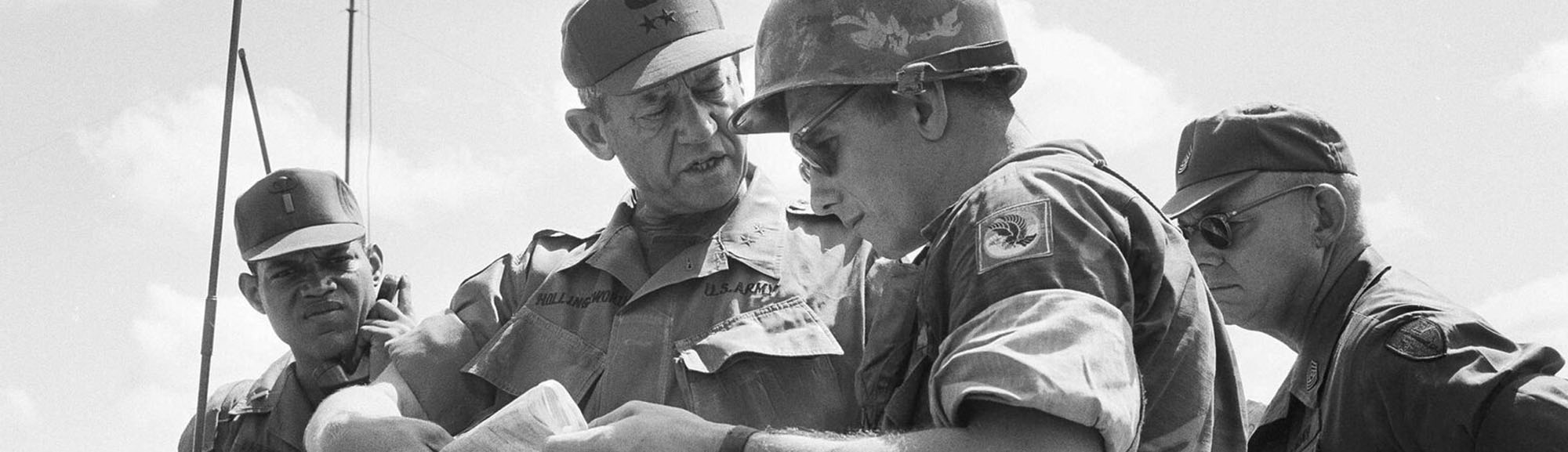

A concerted American advisory effort in Vietnam began in 1956, when the last French troops left their former Indochina colony under the terms of an international agreement that followed their May 1954 defeat at Dien Bien Phu. Twelve years later, the U.S. military commitment in Vietnam totaled about 500,000 troops. That included 5,500 field advisers, officers and noncommissioned officers, who served with ARVN companies, batteries, battalions and regiments. These men were liaison officers, instructors and fire-support coordinators. At the height of the American buildup, an adviser controlled medical evacuations, tactical air support, artillery support, supply replenishment and an array of other resources available to those units.

In 1969 the situation changed. The American people were war weary, and the newly elected president needed to fulfill his campaign pledge to end the war. “Vietnamization,” President Richard Nixon’s plan for disengagement, started a phased U.S. withdrawal. The aim was to “de-Americanize” the conflict, bring the prisoners of war home and upgrade South Vietnam’s armed forces so they would be capable of carrying on the fight by themselves.

A reduction in U.S. combat forces and military support created tensions between South Vietnamese units and American advisers—co-vans in Vietnamese. Ties began to fray even in South Vietnam’s elite Airborne Division, which had always been the model for cooperation.

Within the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (the organization in charge of American combat forces), the Airborne Division had enjoyed “favored son” status. General William Westmoreland, MACV commander from 1964 to 1968, held the Airborne in high regard, and the division received priority treatment. A 70-man advisory team, the largest in MACV, assisted the division. Not surprisingly, Vietnamese paratroops participated in some of the hardest fighting. During 1967 and 1968, eight airborne battalions were awarded the coveted U.S. Presidential Unit Citation. But as U.S. support began to diminish the following year, the much-touted airborne brotherhood became more illusory than anyone wanted to believe.

The Airborne co-vans were quality soldiers. The division senior adviser, a U.S. Army colonel, personally selected each officer and noncommissioned officer. Volunteers lined up for those jobs. Service with Airborne Division Assistance Team, also known as MACV Team 162, was considered a plum assignment, even when most combat arms professionals wanted to serve in American units.

More than 30 of the adviser team’s officers would become generals, among them Norman Schwarzkopf, commander of the U.S.-led forces in the 1991 Gulf War, and Barry R. McCaffrey, who later served as director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy during President Bill Clinton’s administration.

The February-March 1971 incursion into Laos, Lam Son 719, was a major test of Vietnamization. A U.S. law passed before the offensive dictated that no American ground troops could be deployed outside South Vietnam. That meant advisers did not accompany ARVN units into Laos. But American tactical aircraft, B-52 bombers and helicopters were allowed to cross the border to provide support.

Lam Son 719 was the first time the ARVN Airborne Division functioned as a tactical entity. For years its battalions and brigades fought as independent task forces. The division headquarters, at Tan Son Nhut Air Base near Saigon, had never operated in the field. Inexperienced staff officers encountered coordination problems and were slow to adapt to the new face of war. The enemy now operated in battalion- and regiment-size formations, not in small guerrilla bands. Tactics that worked before, such as operating from fixed firebases and sending small units out on sweeps, were risky when the North Vietnamese employed massed infantry backed by tanks and heavy artillery. Lack of English proficiency and procedural knowledge hampered coordination with crucial American air support. Previously, U.S. advisers on the ground had handled communications with American aircraft.

Despite glowing reports of victory, ARVN units sustained heavy casualties during Lam Son. The Airborne Division suffered 455 killed, nearly 2,000 wounded and an unknown number of missing, including a brigade commander. It was a stark reminder of the ARVN’s continuing dependence on the United States.

After Lam Son 719 the pace of Vietnamization increased. Some 160,000 Army troops departed in the remaining months of 1971. The number of advisers was also reduced but at a slower pace—3,900 field personnel were still authorized. Because of its importance, the Airborne Division retained its battalion advisers when similar positions were eliminated in other ARVN units. The South Vietnamese now saw the adviser as solely a conduit for U.S. air power. Little advice was rendered and even less was accepted at a time when it was sorely needed, as the war transitioned to a conventional struggle between the North and South.

In the spring of 1972 the leaders of the Communist Party’s Politburo in Hanoi intended to settle the unification question once and for all. The North Vietnamese Army launched an all-out combined-arms attack called Operation Nguyen Hue, named after an emperor who in the late 1700s united the northern and southern areas of what is now Vietnam. The attacks became known to Americans as the Easter Offensive because they began over Easter weekend. The NVA’s thrust across the Demilitarized Zone started on March 30. The North Vietnamese struck in the south on April 5 at Loc Ninh, near the Cambodian border north of Saigon. The town was overrun in two days, and NVA forces almost immediately surrounded An Loc a few miles away. An attack in the Central Highlands began April 14. The three assaults involved 120,000 soldiers augmented with 500 tanks and large formations of artillery.

The Communist leaders assumed that South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu would commit his reserves to protect the northern provinces bordering the DMZ, which would leave Saigon vulnerable when the North Vietnamese took Loc Ninh and An Loc. If An Loc fell, only 60 miles would separate three NVA divisions from South Vietnam’s capital. In the third phase, the Central Highlands attack, two divisions were to hit Kontum Province. The loss of Kontum City, a provincial capital, would allow the NVA to roll up the light defenses farther south and strike toward the coast, splitting South Vietnam in two.

The NVA plan was based on assumptions that Vietnamization was a failure and that Nixon would not respond vigorously because U.S. public opinion had turned against the war. The NVA’s initial successes validated the optimism of the Politburo hawks. South Vietnam’s northernmost province, Quang Tri, had been overrun. In the south, An Loc was under siege, barely holding on. And the Central Highlands city of Kontum was threatened. The NVA offensive seemed to be progressing well. But Hanoi had grossly misread Nixon, who reinforced the South with additional air power, ordered the mining of enemy seaports and resumed the bombing of North Vietnam. Still, U.S. troop withdrawals continued.

South Vietnam committed the entire Airborne Division to stopping the NVA. The division headquarters and two brigades were sent to bolster the defenses in the northern region. The 1st Airborne Brigade, consisting of the 5th, 6th and 8th battalions, reinforced troops defending besieged An Loc.

Before the operation, Captain Mike McDermott was assigned as Team 162’s senior adviser to the 5th Airborne Battalion. The battalion commander, Lt. Col. Nguyen Chi Hieu, let McDermott know that he had expected a more senior U.S. officer and treated him as simply a useful functionary. Hieu did not include McDermott in the planning process or share information with him. When McDermott wasn’t directing air support, Hieu had no time for him. The South Vietnamese colonel failed to realize that the American captain had more combat experience than any officer in Team 162. McDermott had served three tours with the 101st Airborne Division and received the United States’ second highest award for valor, the Distinguished Service Cross, for actions on a search-and-destroy mission in November 1967.

Throughout April and May 1972, An Loc hung in the balance. Successful defensive actions by the Airborne’s 5th Battalion were attributed to the courage of the individual ARVN paratroops and the precision airstrikes directed by McDermott. The captain exposed himself to enemy fire multiple times so he could adjust the strikes. His adroit use of tactical air support saved the day. As the situation stabilized, the American’s tour drew to a close. When he departed, battalion commander Hieu was totally indifferent: no “thank you,” no farewell, no anything. But U.S. officials appreciated McDermott’s contributions, awarding him a second Distinguished Service Cross and a Silver Star for heroic actions in An Loc.

Hieu’s attitude was not an aberration. Lt. Col. Nguyen Van Dinh, commander of the 6th Airborne Battalion, demonstrated a similar contempt for U.S. advisers. During an April battle on the outskirts of An Loc, the 6th was mauled by an NVA regiment. The 80 survivors, including Dinh and U.S. Army 1st Lt. Ross S. Kelly, withdrew to the south. Kelly kept the pursuing enemy at bay by directing a B-52 strike and multiple air sorties. He also encouraged the battalion commander and his men to keep moving when many were ready to quit.

Kelly’s conduct had saved the small force, but Dinh perceived it as a “loss of face”—a junior U.S. officer had become the unit’s de facto leader—and responded by ostracizing Kelly. The division’s senior U.S. adviser was aware of the problem, but instead of confronting it, he replaced Kelly with a recently arrived infantry major. Dinh simply transferred his hostility to the new adviser. He did not share situation reports or his plans. The American learned the details of a pending relief operation at An Loc through U.S. channels. The 6th Airborne Battalion was to conduct an airmobile assault about 6 miles south of An Loc and fight its way into the town.

When the reconstituted 6th Battalion rejoined the battle on June 4, U.S. Air Force and Navy carrier-based fighters paved the way. Tactical air sorties during the day and Lockheed AC-130 Spectre gunships at night reduced NVA resistance. The 6th Battalion linked up with the An Loc defenders on June 8. It was the first South Vietnamese unit to break the NVA stranglehold on the town. Within a few days South Vietnam’s high command declared the siege lifted, even though the main highway to An Loc remained closed and NVA artillery was still pummeling the area. But the paratroops were ordered to break out of the encirclement and prepare for a new mission.

In the euphoria that followed, the international media cited An Loc as the decisive battle of the war. Advisers wrote glowing reports. The impact of American air power was conveniently downplayed, and a “good face” was put on Vietnamization.

More troubling, the reluctance of senior U.S. and Vietnamese officials to address the ARVN’s toxic leadership encouraged intemperate behavior, which was reflected at all echelons in the armed forces. Adviser-counterpart issues were often viewed as the Americans’ fault. Officers like Dinh and Hieu even had many American apologists, whose refrains were: “We don’t understand their culture,” “They are exhausted” or “They have been fighting for a long time, much longer than us.” Enemy fighters faced similar hardships but were enduring them, a fact that never entered discussions about the problems of South Vietnamese troops.

The failed siege at An Loc eliminated the immediate threat to Saigon. The government’s new priority was the northern front. The 1st Airborne Brigade was sent there to join the two Airborne brigades that had arrived in May and helped stop the NVA’s earlier drive toward Hue. A few miles up Highway 1, Quang Tri City was the only provincial seat still in NVA hands. Thieu was determined to recapture the city, even though it had no strategic value. A night attack on June 27-28, followed by an airmobile assault on the NVA rear, unhinged the Communist line.

That momentum was frittered away when the corps commander ordered the Airborne Division to delay its attack on the city. The NVA had time to recover and fortify Quang Tri, positioning troops in the town’s Citadel. The fortress, a mini version of a similar structure in Hue, was a formidable redoubt, with thick stone walls, four ramparts and a wide moat. The 2nd Airborne Brigade, with the 5th, 6th and 11th battalions, was ordered to take it.

The attack began on July 10, but the Airborne Division commander, Lt. Gen. Du Quoc Dong, did not share his concept for the operation with U.S. advisers, and the plan was flawed by multiple violations of conventional assault doctrine. The 2nd Brigade was grossly outnumbered by two full-strength NVA regiments defending the Citadel. Those regiments were reinforced by several battalions with Soviet-made 130mm field guns. Because the attackers failed to seal off Quang Tri, the North Vietnamese could continually resupply and reinforce it. The 5th Battalion, assigned to make the main attack, was not allocated additional troops or given priority in fire support. Three airborne battalions paid the price for the division commander’s ineptitude.

The ill-starred attack was also doomed by Thieu’s meddling. The South Vietnamese president drew an imaginary circle around Quang Tri City to delineate an arbitrary “ARVN-only” zone, where U.S. airstrikes were prohibited. Thieu had been stung by reports that U.S. air power had saved An Loc and Kontum. He wanted to demonstrate that his forces were capable of winning on their own. But the South Vietnamese air force lacked the expertise and aggressiveness to support the campaign.

Once the battle began, paratroops were immediately bogged down in house-to-house fighting short of the Citadel walls. Tempers flared. Dinh, the 6th Battalion commander, railed against the United States’ “failure to help the South.” Thieu’s edict establishing the ARVN-only zone was understood but discounted. During one of his tirades, Dinh said the South Vietnamese were only pawns in America’s war.

The 5th Battalion finally managed to secure a foothold on the northeast rampart of the Citadel. The hard-won gain was nullified the morning of July 24, when a South Vietnamese plane dropped three 500-pound bombs in the midst of the paratroops, killing 45 and wounding scores more. The soldiers had to retreat, and the lodgment was lost. The NVA retained control of the Citadel as well as the approaches to it. The 5th Battalion suffered 98 killed and 400 wounded. South Vietnam could not absorb casualties of this magnitude. Only a few replacements arrived to join the ranks.

The Vietnamese Marine Corps relieved the battered 2nd Airborne Brigade on July 28, but soon became locked in an attritional slog. Thieu was forced to lift his restriction on U.S. airstrikes. Quang Tri was retaken on September 16, and as at An Loc, the area was reduced to rubble. The psychological victory attained by capturing a small provincial capital did not offset the irreparable loss of well-trained paratroops and marines.

With the Easter Offensive blunted, the North Vietnamese delegation at the Paris Peace Conference became less intransigent. Hanoi’s emissary, Le Duc Tho, was an obdurate negotiator when Operation Nguyen Hue was at its high-water mark. Now a settlement appeared in the offing. Most South Vietnamese officers, however, feared the United States would betray them. When Nixon’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, said in late October that “peace is at hand,” it created irreparable fissures.

The bitterness was palpable. Major Hugh Walker, adviser to the 3rd Airborne Battalion, said his ARVN counterpart barely tolerated his presence. Walker was completely shut out. His report explained the issue: “No information on Bn [battalion] activities or missions is offered….Acceptance of advice or suggestions is neither requested nor so far accepted if offered. Discussing of Bn tactics, ie, that of deploying companies in the attacks instead of platoons and squads, are received almost as insults or disbelief.”

Nixon announced a cease-fire agreement with the NVA effective at 8 a.m. local time, Jan. 28, 1973. The POWs would return home, and all Americans would be out of the combat zone in 60 days. On the night of the 27th, there was considerable anxiety. No one knew how either side would react. Artillery fired back and forth across the Thach Han River just south of Quang Tri, the demarcation between the two combatants. But near the appointed time the guns fell silent.

One adviser recorded the situation: “The artillery ceased firing at approx. 0815 hrs, 28 Jan 73. When this happened, the NVA crossed the river all along the front & planted flags on the shore. Leaving their weapons on the shore, they walked up to the friendly unit. The South VN would not shoot because they were unarmed. They formed circles of NVA & SVA and had pleasant chats.”

The scene along the Thach Han River was placid compared with other areas where fierce fighting raged. Land-grabbing was in full force, and control of villages shifted from one side to the other. Throughout the country, South Vietnamese and Viet Cong flags were planted to show ownership. The North Vietnamese used the blue-and-red Viet Cong flag, not their own red flag with a yellow star, trying to maintain the facade that the war was just a southern insurgency led by the Viet Cong to throw out the “imperialists and their puppets.”

On February 6, Team 162 conducted a memorial service at Tan Son Nhut Air Base. Only 40 advisers were in the formation. During the war, 26 Americans had died serving with Team 162. Five were killed during the Easter Offensive. General Frederick C. Weyand, MACV commander from 1972 to 1973, attended the service. Noticeably absent were senior South Vietnamese officers from the Joint General Staff (similar to the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff) and the Airborne Division. They registered their objection to the cease-fire by snubbing the team.

At the ceremony, the experiences with other ARVN divisions were offered. Several regimental assistance teams had to be pulled out because commanders and soldiers were openly hostile. American planners failed to anticipate the backlash directed at co-vans. Rapport nurtured over a decade of mutually shared hardships dissolved as the Americans’ final departure drew near. One colonel summed it up when he said, “We have just witnessed the ragged edge of Vietnamization.”

Two years after the cease-fire, the NVA initiated probing attacks to test the U.S. response. When there was none, a major offensive was launched. Nixon’s resignation and a hostile Congress put an end to aid for South Vietnam. Without U.S. assistance and air support, the ARVN disintegrated. Initiatives to ensure that South Vietnam’s armed forces were capable of standing alone failed completely. The huge advisory effort and billions of dollars in sophisticated weaponry had no effect on the final outcome. In the end it was as if Americans had never been there.

—John D. Howard served in the U.S. Army for 28 years, retiring as a brigadier general. During the Easter Offensive, 1972-73, he was a battalion adviser with the Vietnamese Airborne Division.

First published in Vietnam Magazine’s June 2016 issue.