With great power comes great responsibility, as Spider-Man teaches. So does great vituperation, as every American president learns firsthand. The easiest mode of attack against a president is character assassination, and so foes have assailed White House residents as lunatics, crooks, dolts, slobs, cripples, drunkards, or drug addicts. Even that paragon, George Washington, endured accusations of being “a most horrid swearer and blasphemer”—oh, and he beat horses, too.

Actual personality problems have sapped some presidents’ effectiveness. The most common: an ungovernable temper. The first president who could not control himself was the second

president. John Adams being dead, we read his peppery letters, especially to wife Abigail, with delight. Face to face, Adams was not so delightful. When he succeeded Washington in 1797, he had to decide what to do with his predecessor’s cabinet. Nowadays an outgoing administration’s panjandrums resign reflexively, even if expecting reappointment. Adams kept the departing Washington’s entire team intact—a fateful decision.

All those men—Timothy Pickering at State, Oliver Wolcott at Treasury, and James McHenry at War—had closer personal ties to Federalist Party powerhouse Alexander Hamilton than to the new boss, a tilt with major policy implications. Hamilton and friends favored a tough line toward revolutionary France, while Adams sought to negotiate. In May 1800, Adams finally decided to clean house. Nothing wrong with that. But his method was remarkable.

One night as James McHenry was dining he received a note from Adams asking that he call at the president’s house. McHenry duly appeared, and after the men chatted about a minor government appointment, Adams uncorked a tirade, interrupted occasionally by his sputtering subordinate. The president recited a drumbeat of occasions when his secretary of war had screwed up—the Army lacked proper clothing—or dissed Adams by eulogizing the recently deceased Washington so as to cast shade on his successor. Adams called McHenry out as “arrogant,” “dictatorial,” and “subservient” to Hamilton—himself, in Adams’s diatribe, a “bastard” and a “foreigner.” Adams derided his entire cabinet as “mere children.” Shaken, McHenry resigned on the spot, whereupon Adams, evidently shamed by his showing out, praised McHenry’s “understanding” and “integrity.” McHenry ankled anyway, memorializing the tongue-lashing in a memo to Adams that the departing secretary copied to Hamilton.

No one expected mild manners of Andrew Jackson. The hero of New Orleans had killed a man in a duel, and in a Nashville lobby had battled his own junior officers with horsewhip, daggers, and pistols. In the White House, Jackson was as brash politically as he was in person. When South Carolina balked at certain tariffs, claiming they were unconstitutional, Jackson declared that the federal government would collect those levies by force if necessary. He made a jihad of his opposition to the Second Bank of the United States. But late in his second term Andrew Jackson surpassed himself.

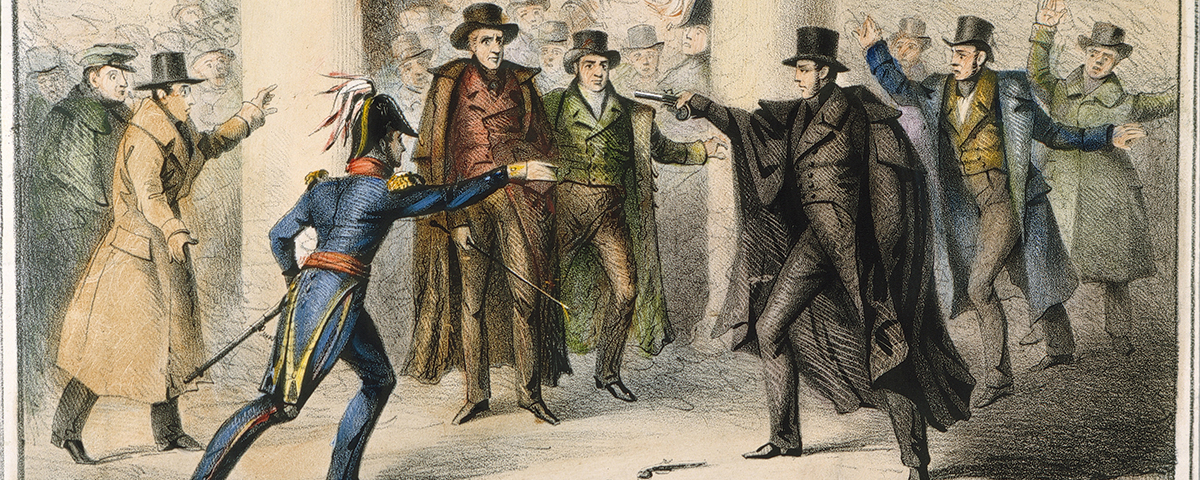

In January 1835, official Washington gathered in the Capitol Rotunda for a congressman’s funeral. As Jackson was leaving the Capitol via the East Portico, a man stepped from behind a pillar and pulled the triggers on two pistols. Both misfired. The would-be assassin, quickly subdued, was Richard Lawrence, a lunatic housepainter convinced Jackson was keeping him from assuming the English throne. Tried and acquitted by reason of insanity, Lawrence spent the rest of his days in asylums, clearly a lone gunman.

However, Jackson smelled a conspiracy. He insisted Lawrence had taken inspiration from a vocal Jackson critic, Mississippi Senator George Poindexter. The president collected affidavits to that effect from obvious scoundrels he personally interviewed in the White House. “The president’s misconduct on this occasion,” wrote an observer, “was the most virulent and protracted.”

No misfire intervened when John Wilkes Booth aimed a pistol point-blank at the back of Abraham Lincoln’s head and made Andrew Johnson president. In 1864, intent on balancing the Republican ticket, Lincoln had tapped Johnson, a pro-Union southern Democrat, as his running mate. On the national stage, Johnson was a nobody. However, one young man had gotten a taste of Johnson’s character in 1860-61, as the country was falling apart.

Charles Francis Adams Jr. was in Washington working as secretary to his congressman father. In conversation with young Adams, Senator Johnson went off on fellow southerners, slamming them as traitors all. Adams, an avid diarist, recorded Johnson’s every imprecation. David Yulee of Florida was a “miserable little cuss….contemptible little Jew….despicable little beggar.” Louisianan Judah Benjamin was “another Jew…. He looks on a country and a government as he would on a suit of old clothes. He sold out the old one; and he would sell out the new if he could in so doing make two or three millions.” Johnson finished with Louis Wigfall of Texas: “a damned blackguard” and bankrupt to boot—typical, in Johnson’s estimation: “the strongest secessionists never owned the hair of a n——.”

In conclusion, wrote Adams, Johnson said somebody “ought to be hanged for all this.”

All three episodes of presidential pique stand out not for vitriol—everybody gets angry—but for indiscretion. In privately berating McHenry, John Adams must have known the other man would spill the beans to Hamilton, who would broadcast them to the world—as Hamilton did, in an incendiary pamphlet. Jackson touted his conspiracy theory far and wide. Johnson trash-talked colleagues to a sprat he hardly knew; imagine what he said to friends.

And so to President Donald J. Trump. Admirers hear and read in Trump’s out-there animosities and drive-by raillery echoes of feisty Theodore Roosevelt and, yes, Andrew Jackson. Trumpophobes call the president crazy enough to invoke Section 4 of the 25th Amendment—the get-this-guy-out-of-here clause. Friendand foe alike marvel at Trump’s Twitter stream. After a recent classic—“Why would Kim Jong-un insult me by calling me ‘old,’ when I would NEVER call him ‘short and fat?’”—chief of staff John Kelly told reporters, through gritted teeth, that he was not paying attention. “Someone…said we all just react to the tweets. We don’t. I don’t. I don’t allow the staff to…Believe it or not, I do not follow the tweets.”

And don’t think of white bears, either.

Is a towering temper a bad thing? Washington thought so; he leashed his own so tightly only biographers know of it. Overtly tempestuous presidents, however, have a mixed record. Most historians think Adams was right to seek rapprochement with France. His outburst at McHenry and the Hamiltonians, however, split his Federalist Party on the eve of a tough election, ensuring Thomas Jefferson’s triumph. Jackson’s dyspepsia did not keep him from accomplishing his goals. Elected and reelected, he bestowed his name on a movement and an era. Jackson’s bizarre vendetta against George Poindexter did trouble that senator, but went nowhere, not blemishing Jackson’s reputation. But Andrew Johnson is, by universal consent, our worst president—a conclusion strongly reflecting the effects of his temperament. At a national moment demanding vision, wisdom, and malice toward none, Johnson, in the words of historian Eric Foner, proved himself “self-absorbed, insensitive to the opinions of others [and] unwilling to compromise.”

Instead of rolling the dice with ire, perhaps take advice young Washington copied from an etiquette book: “Be not angry at table whatever happens & if you have reason to be so, show it not but [put] on a cheerful countenance especially if there be a stranger…”