The CIA man who ran Lima Site 36 in Laos was known simply as “The Customer,” and he commanded a base that didn’t officially exist. The north Laotian site, with its crude landing strip in close proximity to the North Vietnamese border, changed hands almost every year, and it perpetually smelled of death. When the brush around the base was burned to clear defensive fields of fire, unexploded ordnance routinely went off.

After ignoring an abort order, Pararescue Jumper Charley Smith soon realized why it was issued – when MiG-17s attacked his helicopter.

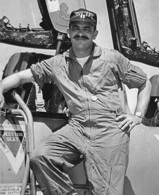

On the morning of November 5, 1967, the site was in Laotian army hands, and U.S. Air Force Pararescue Jumper Charley Smith, a tech sergeant at the time, landed on the small runway in one of two HH-3 Jolly Green Giant rescue helicopters from the 38th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron, based at Udorn, Thailand. American F-105s would be striking the MiG base at Phuc Yen north of Hanoi that afternoon, and if any went down, it would be Smith and his detachment who would cross into North Vietnam to rescue—or recover the pilots.

Hundreds of miles away, at about 8 a.m. at the American airbase at Takhli, Thailand, Captain Bill Sparks of the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing, 357th Tactical Fighter Squadron, was “walking the walls” where extremely detailed and up-to-date maps and photographs of the Phuc Yen target area were posted. Sparks always paid very close attention to the target area and notations of where anti-aircraft positions were located. Of particular interest to him were surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites.

Sparks was on his second tour of duty and had recently come out of the Wild Weasels when his electronic warfare officer, Carlo Lombardo, was shipped to South Vietnam. Though he’d flown 63 strike missions in 1965, the November 5 mission was only his fifth on his second tour. That all added up to more than 1,800 hours’ flight time in an F-105 and 2,600 total hours in fighters.

That day, Sparks was slated to lead the fourth flight of four supersonic F-105D Thunderchiefs to bomb Phuc Yen’s hangars, roughly 75 miles northwest of Hanoi. Flying “tail-end Charlie” was the worst position, as all the enemy gunners would be ready. And Phuc Yen was no soft target, with literally thousands of 37mm, 57mm, 88mm and 120mm guns supported by about 15 SAM sites, two airfields and hundreds of thousands of people on the ground with rifles.

Strike Mission

When Sparks took off shortly after 12:30 p.m., he formed up with the rest of his group and joined the air tankers. A group of F-4s was flying MiG combat air patrol (MiGCAP) that day to protect the strike planes from enemy fighters, and four Wild Weasels were with the flight to locate SAM sites.

As the aircraft made their way toward the target, they regularly refueled from the air tankers that would accompany them to about 50 miles from the Laotian/North Vietnamese border and stay on-station during the strike. By the time the strike force left the tankers, each plane had refueled four times.

A string of mountains the pilots referred to as “Thud Ridge” served as an excellent visual landmark as they approached the target area. It pointed right at Phuc Yen, and it was lightly defended.

The Wild Weasels went in first, and Sparks and the rest of the strike force focused on flying in their pod formations, which allowed them to use their jammers to confuse the tracking systems on SAMs.

As the strike force crossed the Red River to enter the target zone, the enemy gunners opened fire. Sparks and his fellow pilots jinked their aircraft, staying high enough so their random movements would throw off the gunners, hopefully allowing them to dodge the hail of bullets coming up at them.

Ten miles from Phuc Yen, flying at about 540 knots, the Thunderchief pilots lit their afterburners and rolled in for the bomb run at 12,000 feet.

Each plane in Sparks’ flight was carrying six 750-pound M117 bombs left over from World War II and originally designed for the bomb bays of B-17s. The first flight in, however, was carrying cluster bombs to suppress the flak. Sparks always thought that was like trying to bail out the ocean with a teacup, but it had to be tried.

Each plane in Sparks’ flight was carrying six 750-pound M117 bombs left over from World War II and originally designed for the bomb bays of B-17s. The first flight in, however, was carrying cluster bombs to suppress the flak. Sparks always thought that was like trying to bail out the ocean with a teacup, but it had to be tried.

The first two flights of four aircraft each flew in, dropped their bombs and cleared the target without any problems, but the third flight went in late, causing Sparks’ flight to make its bomb run at the wrong angle.

As Sparks descended toward the target, his flight caught the full attention of the enemy anti-aircraft gunners, who threw up so much fire that it obscured the airfield. Dropping through the layers of flak, Sparks eventually got to where he could see the target and led his flight in.

Without the luxury of smart bombs, Sparks dropped his ordnance and pulled up, rolling to each side to allow the rest of his flight to see him and join the pod formation to confuse the SAMs. Photo interpreters later determined that 18 of the flight’s 24 bombs went right through the roof of the hangar, leaving nothing intact.

At Lima Site 36, Charley Smith and the helicopter crews were in the radio shack, listening to the strike progress. The rescue and recovery crews were always on alert during the missions, and they didn’t stand down until the last American aircraft cleared the target area.

As they huddled around the radio, Smith and the rest of his detachment heard the strike go in. All four flights dropped their bombs, and no one had radioed that he was hit.

“No mission today,” one of the helicopter crewmen said, and Smith went outside to cook C rations over a campfire. When they got the official confirmation that the strike planes were back over friendly territory, the two Jolly Greens and four A-1 Skyraiders that made up the rescue and recovery detachment would fly to Lima Site 98, where the headquarters of General Vang Pao of the Laotian army was located. Even though Site 36 was still in Laotian hands, it was considered too exposed for the aircraft to stay overnight.

Incoming SAMs

With his bombs released and the hangar destroyed at Phuc Yen, Sparks waited for his flight to form up in the pod formation. Before the others could get back in formation, however, the radio came alive with calls reporting SAMs in the air. Sparks glanced around and saw three of them coming up toward him as he climbed to get above 4,500 feet, an altitude where the chances of being hit by groundfire dropped drastically.

Turning right would be the best way to get away from the SAMs, but it would put Sparks and his flight over heavily defended bridges and a rail yard. So Sparks took a gamble, dropped the nose and made a supersonic run across the rice paddies at an altitude of about 50 feet.

The first SAM lost the flight and hurtled skyward. The second missile slammed into the ground, and the third veered off to the right. Just then, one of the Wild Weasel pilots called out that he’d been hit.

Sparks pulled the stick back to get out of range of the Vietnamese guns, but it was too late. Three 57mm rounds punched through his F-105. The first hit the air turbine motor right in front of his knee, the second slammed through the bomb bay and the third hit the rear end of the plane.

The air turbine motor caught fire, fuel in the bomb bay caught fire and a third fire started in the rear. The cockpit filled with smoke, blinding Sparks. To regain some visibility, he popped his canopy, and the slipstream cleared the smoke.

The damage to the aircraft began to register, gauges started failing. Eventually, only the compass remained functional. The last time Sparks was conscious of his airspeed, he was doing mach 1.2, climbing as high as he could, and he saw his wingman join up with him. The fires in Sparks’ plane spread, and he was called in as a SAM several times by American pilots.

“That’s not a SAM, that’s Sparkie!” his wingman kept calling.

With his F-105 aflame all around him, Sparks’ main goal was to cross the Red River. Rescue missions weren’t allowed north of the Red River, as the slow-moving Skyraiders and Jolly Greens would be shot to pieces.

Fire melted the right-front-quarter panel of Sparks’ plane, and he lifted his right leg to keep it out of the flames licking at his foot. The rudder pedal melted and fell onto the floor, but Sparks needed to get past that magic line where he would at least stand a chance of being rescued.

The flames reached the 390-gallon fuel tank near the bomb bay, and it blew the doors open. Moments later, the right landing gear caught fire and the tire blew, throwing the gear down to be ripped off.

Just as he crossed the Red River, Sparks lost control of his Thunderchief. When he thought it was going into a flat spin, he ejected. When he punched out, he was going about 250 knots at 24,000 feet. As he fell, Sparks remembered his previous ejection, when his parachute risers scraped the bottom of his chin as the chute opened.

At 10,000 feet, Sparks heard the mechanism that automatically opened his parachute go off, and he tucked in his chin, but the risers still cut his chin as the canopy deployed. Sparks hauled on one side of his risers to steer the chute to the other side of the river. Ahead were several large open areas that would have been perfect landing zones, had they not been in sight of North Vietnamese villages. Sparks knew that if the villagers captured him, they would beat him before turning him over to the military.

Sparks hauled his risers again and managed to glide about four miles, putting two ridgelines between himself and the nearest village. When he spotted a field of what he thought was elephant grass, he headed for it.

Just before he struck, Sparks realized the elephant grass was actually bamboo soaring about 75 feet high. He crashed down through it, the sharp bamboo ripping up his parachute. He fell free the last 30 or 40 feet to the ground, landing on his heels.

Sparks broke both ankles, chipped bones in both ankles and feet, broke his right kneecap and dislocated his right shoulder. What hurt most was when his ankle slammed into his groin.

The Cavalry Is On Its Way

Meanwhile, back at Lima Site 36, Charley Smith was in the middle of cooking his C rations when the door to the radio shack flew open.

“Scramble! Scramble! We’re going north,” the shouts went up, and Smith ran to his Jolly Green as the pilots started the engines.

As the helicopters got airborne, the crew mounted the door gun and Smith got into his gear. He carried an M-16, a .38 revolver and a survival knife. Pararescue Jumpers weren’t allowed to carry grenades for fear that they would be hit by ground fire and wreak havoc inside the helicopters. Smith carried several anyway, not wanting to be on the ground without them. He kept them hidden in his helmet, and as he picked it up to put it on, he slipped the grenades into his pants pocket.

A few months earlier, famed American pilot Karl Richter had been shot down on his 198th mission. Smith was sent to rescue him, but Richter had fallen down a cliff and was dead by the time he reached him. The whole time Smith was on the ground loading Richter into a Stokes basket, he could hear the enemy in the jungle around him. For that mission, Smith was awarded the Silver Star.

As the helicopters now sped to rescue Sparks, Smith scanned the ground below, looking for enemies. The weather was clear and perfect for flying, even if it was stiflingly hot with humidity around 90 percent.

As the helicopters now sped to rescue Sparks, Smith scanned the ground below, looking for enemies. The weather was clear and perfect for flying, even if it was stiflingly hot with humidity around 90 percent.

Struggling through the bamboo, Sparks found it was so thick that the only way to move was to crawl, and the going was slow. A couple times, Sparks found himself several feet off the ground on the thick bamboo and had to pull himself back down. He finally emerged into dense ferns.

Sparks had two survival radios and three batteries with him. One radio was issued, the other he had appropriated at some point during his tour of duty. Besides his issued .38 revolver, Sparks also had a small .25-caliber automatic pistol and seven knives. For hydration, he carried six baby bottles full of water, and he drank one as he waited in the ferns, listening to his radio.

The number three man in his flight that day was Major Frank Billingsley, whom Sparks had recently instructed in how to run the rescue combat air patrol (RESCAP)—the assignment to take care of the downed airman and provide cover until the Jolly Greens and the Skyraiders showed up.

“Get the hell out of here,” Sparks told Billingsley over the radio.

“Fuck you, Sparkie,” Billingsley said. “I’m running this thing, and I can see better than you. Shut up. Everything’s going fine, it looks good.”

Billingsley held his position, making wide circles around the area to prevent the enemy from getting a fix on Sparks’ position, but his fuel was running low. He had to break off and fly back to refuel off the tanker. To Sparks’ surprise, Billingsley was back 26 minutes later—which meant the tanker had crossed into North Vietnam, risking taking enemy fire with 100,000 pounds of aviation fuel on board.

Billingsley told Sparks the cavalry was on the way. Sparks thought Billingsley was lying.

Had the American commanders on the ground had their way, the cavalry—in the form of Smith and the men flying the Jolly Greens and Skyraiders—never would have showed up. As it turned out, those commanders had good reason to call the mission off.

“We Know What We’re Doing”

Captain Harry Walker was flying Smith’s Jolly Green that day, and as they made their way toward Sparks, they received orders over the radio to turn back and abort the mission. They were told that Sparks was too far north, and rescuing him would be too great of a risk.

Walker made a decision that saved Sparks’ life.

“There’s too much static,” Walker said. “I can’t hear you. We’re going in to get him.” There were a lot of rescue pilots Smith didn’t give a damn for, but Walker was one of the good ones.

Knowing there were MiGs in the area didn’t diminish the threat of enemies on the ground, and Smith kept his eyes open. Anyone wearing pajamas would be a target. On another mission, Smith had had to descend to the ground on a line, and while he was halfway down, he spotted an old man carrying an AK-47. Smith hoped the old man would keep the AK pointed down, but he raised it, and, from his perch on the penetrator, Smith cut him down with his M-16.

The Skyraiders reached Sparks about an hour after he was shot down but, to him, it felt more like two or three years. One of the Skyraiders dropped a smoke grenade well away from Sparks’ position, and Sparks radioed that he was marking the wrong spot.

“We know that,” the pilot said. “We know what we’re doing.”

When a pilot was down, the Skyraiders would locate him, then mark two positions away from him with smoke to draw the enemy to the wrong spot. When it was time for the Jolly Greens to go in, they would tell the pilot to pop a smoke grenade or fire a flare; then they would pick him up.

Sparks, in addition to his knives and guns, carried pen flares, which looked like fountain pens and shot small flares. Sparks fired several, bouncing one off the canopy of Smith and Walker’s Jolly Green as it flew overhead.

As the helicopter went into a hover and Smith prepared to drop the penetrator—a heavy anchor-shaped device that penetrated the jungle on a cable and worked as a seat—four North Vietnamese MiG-17s showed up. Someone frantically called over the radio for the Jolly Green to get out.

As the helicopter went into a hover and Smith prepared to drop the penetrator—a heavy anchor-shaped device that penetrated the jungle on a cable and worked as a seat—four North Vietnamese MiG-17s showed up. Someone frantically called over the radio for the Jolly Green to get out.

“Fuck you,” Walker shouted. “I’ve got more important things to do.”

The Jolly Green was a sitting duck. A MiG, screaming in at about 300 mph, fired a missile at the stationary target. But the pilot had waited too long. The missile didn’t have time to lock on, and it shot past the helicopter, exploding on a hillside in the distance. Luckily, that was the only missile Smith saw fired that day, and the MiGs disappeared after that.

Smith later realized that whoever had called the mission off in the first place had probably known about the MiGs in the area.

When the penetrator came down, the injured Sparks scrambled toward it and no sooner took his seat and strapped himself in when he felt himself hoisted aloft. With Sparks clinging to the penetrator—which was still dangling beneath the helicopter, being reeled in—Walker and the rest of the rescue and recovery group flew as fast as they could toward safety. Everyone was spraying the jungle with bullets, so Sparks pulled his .38 and fired off six shots, thinking he might as well do his part.

When Sparks finally made it into the helicopter, the crewmen were cheering. One of them turned to Smith and said, “Tell that son of a bitch not to die until we get to a hospital because we need a live one for a change.”

Smith kissed Sparks on the forehead, then got to work. The first thing he did was strap a parachute on Sparks and hand him a rifle. Though Sparks’ injuries were numerous, Smith couldn’t get to them right away because Sparks went into shock almost immediately. Smith elevated Sparks’ feet, and all the crewmen piled coats on him. As Smith pulled an IV out of his medical bag, Sparks started recovering from the shock. “I don’t think I need that,” he said.

Sparks turned down Smith’s offer of morphine—but later accepted a small bottle of Jack Daniels that Smith passed to him. He thought it was the best medicine he could have.

“Low Fuel” Light

As the Jolly Green carrying Smith and Sparks crossed back into Laos at 14,000 feet, it needed to refuel. One of the crewmen tapped Sparks and told him he should see it.

Sparks lifted his head and watched the helicopter approach the tanker while all the “Low Fuel” lights were blinking wildly. What really took Sparks’ breath away, however, was the sight of the sun’s last light shining crimson around dark black clouds. At that, Sparks started crying.

Originally, the helicopters were going to take Sparks to northern Laos, but they took him to Nakhon Phanom instead. When the Jolly Green landed there, an ambulance was waiting, and it rushed Sparks to a hospital.

Sparks was supposed to be checked out at the hospital there, but the X-ray machine was broken, so a plane from Takhli was sent to pick him up. He made it back to Takhli at about midnight, but it was a while before he could be treated—it was time to party.

Sparks was taken on a parade around the base and given a few drinks. He was the first pilot to be returned to Takhli after being shot down in almost a year.

The rescue of Captain Bill Sparks was the second-farthest north rescue during the war. For his part in the mission, Smith was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

In addition to his DFC and Silver Star, Smith was awarded the Bronze Star Medal and seven Air Medals.

For Smith, saving Sparks ranked as one of the most exciting missions of his tour of duty in Vietnam. It was a good mission with a great result. Despite the inherent danger, it was what Pararescue Jumpers lived for. The dozen or so Pararescue Jumpers based at Udorn were on a rotation for mission assignments; they all fought for who would get assigned the missions up north.

After rescuing Sparks, Smith was only in-country for another two months. He went on to teach at the Pararescue Jumper school in Hawaii and eventually trained for recovery of Apollo spacecraft.

As a 29-year-old Pararescue Jumper, Smith’s year in Vietnam gave him the chance to do what he had trained for, what he had prepared for.

The rescue of Captain Bill Sparks by Smith and his intrepid team epitomized the selfless dedication of the hundreds of PJs and their support crews who served during the war in Vietnam.

Brandon Darnell, a newspaper reporter living in California, conducted extensive interviews with Bill Sparks and Charley Smith for this story. For further reading about Pararescue Jumpers and combat rescues, see Leave No Man Behind: The Saga of Combat Search and Rescue by George Galdorisi and Thomas Phillips and That Others May Live: The True Sory of a PJ, by Pete Nelson and Jack Brehm.