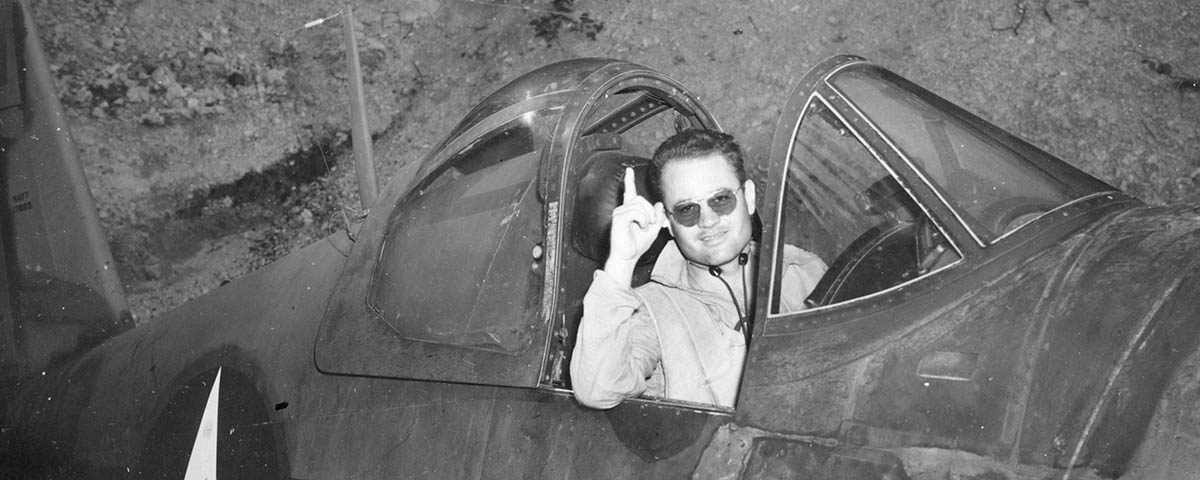

Before the United States officially entered World War II, many young Americans volunteered to serve in foreign air arms. Whether flying for Britain in the Eagle Squadrons or in the American Volunteer Group supporting Chiang Kai-shek in China, those who served as fighter pilots were the spearhead of American intervention, and they quickly became folk heroes. One of the most colorful and controversial members of that unique fraternity was Gregory Boyington.

Boyington discovered a new world in combat aviation after several years as an instructor pilot in the U.S. Marine Corps. The combat experience he accumulated over China and Burma was nearly wasted by a bureaucracy that failed to comprehend the necessities of the new war-and was often willing to shelve talented individuals whose skills were sorely needed at the front. Boyington’s methods of circumventing rules and regulations as well as his often outrageous personal conduct often proved that he was, as he admitted in retrospect, his “own worst enemy.”

Boyington ended the war with 24 aerial victories and earned the Medal of Honor. But his legend continued after the war came to a close. During the 1970s, actor Robert Conrad portrayed him in the television series Baa Baa Black Sheep (later renamed Black Sheep Squadron), making Greg Boyington and his Marine squadron, VMF-214, household names once again, despite some glaring distortions of historical fact and reality in the productions.

Greg Boyington lived life as hard as he fought the war. He died on January 8, 1988, not long after granting this interview to Colin D. Heaton. His observations are candid regarding the war, the Japanese and our own government and military during the war and afterward.

Aviation History: Where did you grow up?

Boyington: We were from Idaho, but we moved to Okanogan, Wash., where my parents had an apple farm, when I was in junior high school. My brother Bill and I had a great environment when we were growing up.

AH: When did you decide to become a pilot?

Boyington: I had always loved the idea of flying. I used to read all of the books about the World War I fighter aces, and I built model planes, gliders and things. I went to the University of Washington and received a Bachelor of Science in aeronautical engineering, and I also played football and did a lot of boxing there. I was there with Bob Galer, who commanded the first fighter detachment on Guadalcanal in 1942. He was shot down several times and always made it back through Japanese lines. Of course, he was usually sober. I also flew during the Miami air races-anything to log more air time.

AH: How did you get involved with the American Volunteer Group (AVG)?

Boyington: Well, I had been in the Corps since 1934 and flying since 1935, and I became an instructor for both basic flight school and instrumentation. That was where I met many of my friends, including Joe Foss. I resigned my commission and accepted the job with the AVG in September 1941, since rank was slow in coming and I needed the money. The AVG was paying $675 per month with a bonus of $500 for every confirmed scalp you knocked down. In 1941 that was the same as making $5,000 a month today. And with an ex-wife, three kids, debts and my lifestyle, I really needed the work. Besides, the government knew damned well what we were doing. They set it up. That was when I learned that Admiral Chester Nimitz maintained files of all of the Navy and Marine pilots and ground crews going over. The only catch was that we had to be secret about the whole affair. We went to San Francisco, where we boarded a Dutch ship, Boschfontein, that was carrying 55 missionaries, men and women, to China. That was our cover, and it stated this in our passports, although my personal cover was that I was going to Java to fly for KLM. It was the same kind of setup the Germans had for going to Spain, and it didn’t fool anyone, especially the real missionaries on board. Dick Rossi and I were pegged immediately. This is amazing, considering that I was not the only one hardly sober enough to remember our cover story and not too careful with his language.

AH: When did you first meet Claire Chennault, and what did you think of him?

Boyington: Well, I met him many times. The first time was in a village called Toungoo, right outside Rangoon, Burma. He was very impressive in appearance and commanded respect, although some of his decisions later alienated him from many of us. He was less than pleased with some of our antics, such as shooting down the telephone lines with our .45s on the train to our billets, holding water buffalo races and rodeos in the street, or shooting up the chandeliers in a bar when they quit serving us. Some of the ground crew had been caught smuggling guns for profit, and that went over like a mortar round. Our radioman had even purchased a wife from her father, and we tried like hell to keep Chennault from finding out. Once before we left for good we began having target practice by shooting at a wall, and it created a problem. A civilian representative from Allison was almost hit by a ricochet, and his report was less than glowing. One of our last stunts was to fly the Chiangs on an escort mission. Before this we were told to give an airshow, a fly-by for the benefit of the Chiangs, Chennault and some other dignitaries. We passed by so low in a rolling turn that they all fell flat on the deck. Our relationship with the RAF [British Royal Air Force] boys was also somewhat strained, since they did not think much of us on the whole. I wondered why they were so snobbish, since they were losing the war. I received more than my share of threats of court-martial, although technically we were civilians, so those threats went in one ear and out a Scotch bottle. My opinion of Chennault began to go downhill following his orders for a greater effort in ground attack missions-missions that were costing us in aircraft and pilots for no appreciable gain. One pilot who was killed was Jack Newkirk. The 3rd Squadron was unusually busy, attacking imaginary depots and unknown numbers of troops in the field. It was all bull. Chennault just wanted to keep the reports active once we ran out of Jap planes to tangle with. Many of the pilots refused to fly those missions, since there was no bonus in killing a tree. Chennault threatened us with courts-martial, and that really began the tide rolling against him. We were civilian specialists working for a foreign government, not his personal command. Finally, Chennault negotiated extra money for strafing, and I volunteered.

AH: How was the AVG organized when you arrived?

Boyington: Well, there were three flights. The 1st Squadron was Adam and Eve, which I was assigned to. The 2nd Squadron was the Panda Bears, commanded by Jack Newkirk, while the third was the Hell’s Angels, led by Orvid Olsen. My squadron saw the least combat and was the last to really get involved. Each squadron had 20 pilots and was completely staffed with ground crews, including mechanics, avionics and weapons specialists. The rest of the staff included a top-heavy Asian administration section, whose purpose was never made quite clear to me. They always seemed to just screw things up. The only time we ever saw them was at meal time. The greatest thorn in my side personally was the executive officer, Harvey Greenlaw. This clown was not a friendly type, and he prepared the paperwork for a court-martial on me and a fellow named Frankie Croft for conduct unbecoming officers, all because we had been holding rickshaw races with the locals. He saw us pulling these two rickshaws with the drivers sitting in luxury as our passengers. The bitch of it is we had to pay these drivers for the privilege of pulling their rickshaws. Greenlaw was still a pain in the ass even after we transferred to Kunming, China.

AH: How did you avoid any legal problems from Greenlaw?

Boyington: I simply told him that if he made any problems for me I would introduce him to a few rounds of good old hooking and jabbing. I think I also mentioned the fact that accidents happened, and sometimes those Japanese bombs that lay around unexploded had the habit of going off unexpectedly-you never knew who might get hit. He finally got the message.

AH: What were the conditions like where you were staying?

Boyington: Absolutely the worst shit-holes you could imagine. People did their toilet business right in the street. Sanitation was unheard of, and the various diseases that we witnessed were enough to convert even the most adventurous of Romeos. There were these dogs, real nasty mongrels that were wild and fed off of the dead and dying people. They were the best-fed inhabitants, but they were never really a danger to anyone, I suppose.

Boyington: I began flying familiarization with the Curtiss P-40s that we had been issued, as well as the P-36 types that were around. All of us went through this training evolution. This was in November 1941. The P-40s were aircraft that we had Lend-Leased to Britain, and which had been loaned from the RAF to us again. We got the idea to paint shark mouths on them after someone found a picture in a magazine showing an RAF P-40 in North Africa painted that same way. My first flight in a P-40 was something of a show, since I had always preferred to make three-point landings in the planes back in Florida. I had the cockpit check and took off, and when I tried to land I bounced, so I slammed the throttle forward for another go around. The result was a manifold gauge that ruptured, and when I landed I was given a stern reprimand about gunning the Allison engines. I started flying combat with Adam and Eve in December, and I remember thinking when we heard about Pearl Harbor that it was only a matter of time before we would be brought back into the U.S. military.

AH: What were the flying conditions like?

Boyington: Well, first off we were lied to about everything. The aircraft were garbage, with spare parts a virtual unknown and the tired engines barely able to get us off the ground. Every takeoff-let alone flight-resulted in a serious pucker factor. The maps we were supposed to use were the worst I had ever seen. Whoever made the maps had either never even been to those places or was more drunk than I was when they sat down to create those worthless objects. Some points of reference were more than 100 miles off, and the magnetic declination was worthless. I remember one of the maps had a major road listed not far from a river. Flying over it, we saw that not only was there no river, but the major road turned out to be a series of paddy dikes. Go figure. The weather could also get you into trouble, and we had no meteorological reports, not like today, and not even as good as what we had during the Pacific campaign. At Kunming we had a 7,000-foot runway that seemed to never get completed, even after five years of constant work, not until our military came in well into the war. Now take into account the greatest lie of all, that the Japanese pilots were pathetic and lacked good vision. I can tell you from firsthand experience that the best men ever to fly a plane in combat were the Japanese, especially the Imperial Navy pilots. Those guys were no joke. If you screwed up you were done for, end of story. We also never had radar or a modern air warning system. However, we did have a series of visual lookouts and a system of telephone relays, and-considering the hundreds of dialects and different languages on this massive line system-things still got done. Anyway, we were ordered down to Rangoon, and I managed to get there with the squadron on February 2, 1942.

AH: Describe fighting the Japanese in the P-40. How did it compare to the Mitsubishi A6M Zero?

Boyington: The Zero was legendary in its agility, due to its light weight and turning radius. No one could turn inside a Zero, but the Zero could not catch us in a dive, which proved to be a life insurance policy. However, most of our fights were against other aircraft, like the I-97 [Nakajima Ki.27]. We developed the tactics of hit and run. Dive down from higher altitude and strike, continue the dive and convert air speed into altitude for another attack. The other plus for us was the fact that we flew three element flights, with the top cover waiting until the other two had attacked. Once the Japs scrambled to intercept us, the top cover would swoop down and pick them off. We also had the advantage of heavier armament-two .50-caliber and four .30-caliber machine guns, with later versions having all 50s against their two 7.7mm machine guns. We also had armor plate in the cockpit and self-sealing fuel tanks. The Japs had none of those, and it cost them dearly throughout the war.

AH: Your group suffered a series of accidents, didn’t it?

Boyington: Well, we had three Curtiss Wright CW-21 Demons, designed for high-altitude interceptor duty. All three of those ships flew into a mountain on December 23, with only one pilot surviving, Eric Schilling. We had a P-40 come down during a night mission in conjunction with the RAF. It crashed into a parked car that was giving headlight visibility, and a man sleeping in the back seat was killed. The prop tore the car apart, and the other men bailed out, forgetting the guy in the back. There was also an incident where I was escorting a [Douglas] DC-2 carrying General and Madame Chiang, the same day as the airshow with a flight. We were never told the destination, so we had to shadow the transport. All six of us ran out of fuel and landed belly-up in a Chinese cemetery. We drove out in an old American truck driven by a guy who knew nothing about driving-a real odyssey, during which we were nearly shot by mountain bandits. These were feudal lords who would rather fight each other than fight the Japanese. We later recovered the aircraft, and no pilots were lost. There were other incidents, but those were the most memorable. Once, during an air raid, while we were at the Silver Grill, a bar we used to frequent where the chandeliers became targets, I had been talking to Wing Commander Schaffer. Schaffer, who had been in the Battle of Britain, was doing some experimental night flying in a Hurricane, which was a serious boost to the Brewster Buffaloes they had in the RAF day squadron. As the bombs began to fall, we bolted out and headed for the trenches. I remember hurdling a high railing and landing in a ditch. Somehow I had unconsciously managed to grab two bottles of Scotch that survived, and I considered it an omen. Another event occurred on February 7, 1942, when Robert Sandy Sandell, the group leader, was killed test-flying his P-40. RAF witnesses said he inverted and appeared to be stalling, but that he recovered. It would appear that he pulled back on the stick too hard and half-rolled into an inverted crash. That was a sad day-he was a great guy. The next day only a few of us could attend the funeral due to duty requirements. Once, during an air raid over the strip, I jumped into my P-40. To make a long story short, the maintenance had not been carried out, and I crashed, really banging myself up. I tore up my knees, and my head was split from the gunsight. I managed to crawl out of the wreckage, since I was afraid of fire, but I was barely able to make it. Meanwhile, an entire group of Chinese stood around watching, never offering to help. I was really pissed at the time, but you have to understand that these were poor people, who believed once you saved a man’s life you were completely responsible for him. To make matters worse, we had a wedding one evening-one of our guys from 3rd Squadron, John Petach, got married to a beautiful lady. During the wedding I sat next to Duke Hedman, the AVG’s first ace, since I could not really stand up very well. During the ceremony the air raid sounded, and I was left alone. I decided to hobble out and jump into a trench. I actually jumped off a cliff in the dark, further injuring myself and undoing the repair work that the doctors had already done. After this I was flown to Kunming and placed in the hospital. Within a few weeks I had my knees tapes up real good and began flying again. This was when Chennault had converted some of the P-40s into dive bombers, and I had had enough.

AH: When did you score your first victory?

Boyington: Right after we arrived in Rangoon. We took off on a bogey call on January 26, 1942, and we ran into around 50 to 60 Japs. We were severely outnumbered by the enemy, who were flying I-97-type fighters. They were about 2,000 feet above us and diving down. Pretty soon I was all alone, as everybody else had decided to run for the deck. I pulled over to the right to avoid the crowd, and I spotted two I-97s and closed with them. As I fired at one, the other pulled a loop over me, so I had to break off and compensate for the maneuver. I just gave up and followed suit, heading for the deck. Then I pulled up and climbed. I spotted another fighter and decided to drop the nose and close in, firing as I gained on him. Suddenly, as he was almost filling the windscreen, he performed a split-S that any instructor would have envied, and I then noticed that I was not alone-his friends had joined in. I got smart real fast and again took a dive and ran for home, no claims. When I landed I found a Jap 7.7-millimeter bullet in my arm, an incendiary that gave me a nice scar. I also found that I had been reported shot down. This first crack at the Japs was a disaster, and all of us were seriously upset with our dismal performance, especially since Cokey Hoffman had been killed. The first kill came two days after this. I got two, and the flight scored a total of 16 with no losses to us. The next kills came soon after. We had already taken off on two false alarms. Finally, on the third hop, I saw a lone I-97 and took him out over the bay at the Settang River. I got three more on one mission, two close together. The third was an open-cockpit fighter, and took a long time to go down, even after I popped a lot of shells into it. I pulled up next door and saw the pilot was dead, his arm just flapping in the breeze. I fired one well-placed burst to collect the money. At that point I had six confirmed with the AVG. [In actuality, the AVG credited Boyington with 3.5 victories.]

AH: There is an ironic twist to this mission regarding one of the AVG pilots, right?

Boyington: Yes. Two RAF Hawker Hurricane pilots had been flying above 50 Japs of the main force. They saw a P-40 and thought he would join them, but instead the AVG pilot threw himself into the whole group, with Japs all around him, guns blazing and confusion all over the place. The two Brits dropped to assist, cursing the crazy man who had started the melee. They all managed to get out of it, and the Brit I was talking to dropped a 7.7mm slug on the bar. He found it in his parachute after he landed. The American turned out to be Jim Howard, and it figured that he would get the Medal of Honor for doing the same thing against the Germans later.

AH: I believe you met Lt. Gen. Joseph Vinegar Joe Stilwell. What did you think of him?

Boyington: They did not come any better. He was a real fighter. The candy asses sitting in Washington attending cocktail parties second-guessed his evacuation of Burma. The British really harangued Stilwell because Burma fell. They always failed to mention that he had only Burmese, Indian and Chinese troops under his command-no American or British forces-and they were not adequately supplied. Stilwell was a real soldier, and he thought no more of sharing a can of grub with an enlisted man than pulling his boots on. Few people have earned my respect. He’s one of them. This was when we were evacuating Burma as well, and we learned that one of our mechanics had purchased a mascot, a tame leopard. We used to play with it, although I was never completely convinced that the animal would not hurt one of us. We played with it anyway to keep it user friendly, and it was always well fed.

AH: When did you return to the Marines?

Boyington: Well, the AVG was being disbanded by July 4, 1942, and Chennault informed us that we all were to be inducted as lieutenants in the Army Air Corps, regardless of past affiliation. I did not agree with that arrangement, especially since I was the only regular pilot and the rest were reservists. I had a major’s commission waiting in Washington with the Marine Corps, and I was not about to sacrifice my gold wings for dead lead. I mentioned the written agreement, but Chennault was having none of it. Besides, majors make more than lieutenants, and when I heard about this from Chennault, my Sioux-Irish blood began to boil. I was not alone, either. Besides, Chennault had pissed me off when he placed a two-drink maximum on my nights out. He never said how large or small they had to be. He even had spies watching me. He was also less than pleased by the fact that we all enjoyed the company of the local girls, and I was no angel. I suppose we did not pass his morality test or something. Another thing that irritated many of us was when the incompetent administration staff told us that we could not get paid for our kills, or even for our monthly back pay, because they had lost some of the after-action reports. I knew damned well that they were not lost. I just wanted to know who was collecting our money, or if Chiang Kai-shek was too cheap to pay us once he knew we were all going back into American uniforms. I said to hell with them and caught a plane to Calcutta along with three other AVG men, all of them bound for the Gold Coast of Africa to ferry new P-40s. I was more afraid of dying in that DC-3 over the Hump with ice clinging to the wings and propellers than I had been when I had a few dozen Japanese fighters around me. I made Bombay, then found that Chennault had issued an order banning me from U.S. military transports and directing that I be drafted into the Tenth Air Force. Well, not to be outdone, I boarded a ship, SS Brazil, which was headed for New York, via Cape Town. I wish I could have seen the look on Chennault’s face when he learned I was Stateside.

AH: What did you think of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and Madame Chiang?

Boyington: Chiang was a legalized bandit, stealing what was not nailed down while pretending to command the Chinese army fighting the Japs. His wife was the brains of the outfit. None of us really had much respect for him, but his money was good when it was paid.

AH: What happened following your arrival in New York?

Boyington: I landed in New York Harbor in July, caught a train straight for Washington, D.C., and placed a letter of reinstatement, citing my agreement with Nimitz. I was told to go home and await orders, so I did. After a few months I went back to my job of parking cars, the same job I had in college. I later learned that my orders were delayed, due to a personal grudge held by someone. All 10 of us former Marines who fought with the AVG were in the same boat. In November I finally sent an express letter demanding a resolution to the problem, and three days letter I was ordered to San Diego.

AH: What was your transition like?

Boyington: No real problem. I left Dago and went to the South Pacific, where this story really takes off.

AH: The television series starring Robert Conrad seemed to upset several of the former Black Sheep, from what I have heard. I also understand that there was actually a Colonel Lard (played by Dana Elcar) and a General Moore (played by Simon Oakland). How much of the series was pure Hollywood and how much was based on reality?

Boyington: Oh, the whole damned thing was Hollywood, but I guess that’s showbiz. Yes, there was a Brig. Gen. James Moore, chief of staff of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, and he was a real stand-up guy. He took care of us and kept Lard off our backs. Lard [Lt. Col. Joseph Smoak, operations officer of Marine Air Group 11] was a real by-the-book Marine, but unlike most of the characteristic backstabbers, he had pulled his time when it counted. He had served in China, and I respected him for that. I was simply the kind of officer he could not understand. I have no ill will toward him or anyone.

AH: How did you get back into flying combat?

Boyington: A twist of fate. When I hit Espiritu Santo, I became assistant operations officer, a dead-stick assignment that was not going to work. The good part about the posting was that I was able to meet some old friends again, such as Bob Galer, who had scored 11 kills, and Joe Foss, who was so sick with everything from malaria to malnutrition I did not even recognize him when I saw him. Another old friend I saw again was Kenneth Walsh, who scored 20 kills and earned the Medal of Honor, before being shipped home immediately afterward. It was in May 1943 when I was chosen by Elmer Brackett to be his executive officer for VMF-222, and I checked out in the Vought F4U-1 Corsair. But as fate would have it, he was promoted and left, leaving me with the command. During my tenure there I never even saw a Japanese aircraft.

AH: I believe you were involved with the Lockheed P-38 mission that killed Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. How did that come about?

Boyington: The P-38s were on Guadalcanal with us, and they had been ordered to make the intercept, due to their range and speed. We helped plan the trip for them, including logistics and obtaining meteorological reports. We knew about the mission on the quiet, and I told the men not to say anything. We did not want the Japs to know we had broken their new code. However, soon Naval Intelligence was interrogating everyone on the island, since word had leaked out. At this point my combat career was almost ruined when my ankle was broken in a football game and I was sent to Auckland, New Zealand, to recuperate. Shortly after this, VMF-222 scored 30 kills against the Japs. I guess they were waiting for me to leave. After I healed up I was bounced from one squadron to another, although always in a nonflying status. One of my jobs was to process the disciplinary paperwork of certain officers and enlisted men. This was where I got the idea to try and form a squadron. I spoke to the MAG-11 commander, Colonel Lawson Sanderson, who had led more of a charmed life than anyone I knew. He gave his off-the-record approval, and I went to work, collecting pilots wherever I could find them. Not all of these men were fighter pilots, but anyone could be converted, or so I thought. Unfortunately, Sanderson rotated out and Lard entered the scene. Well, the only thing left to do was choose a squadron name. One of the men suggested Boyington’s Bastards, and I liked it but knew that would not fly. I suggested Black Sheep, since we were not the typical, picture-perfect material glossing the magazines of the day. The name stuck, as did my two nicknames, Gramps and Pappy, due to my age.

AH: When was your first mission as a squadron?

Boyington: September 16, 1943. We had just arrived in the Russell Islands. We had 20 Corsairs broken up into five flights to escort 150 [Douglas SBD] Dauntless and [Grumman TBF] Avenger bombers on a mission to Ballale, near Bougainville. We maintained radio silence and thought about the 600-mile round trip over anything-but-friendly terrain and open ocean. We ran into a heavy cloud base, lost sight of the bombers, and dropped below the clouds to try and pick them up. Sure enough, I saw the bombers doing their stuff on time and on target. However, we had another problem then-we were jumped by 40 Zeros with full fuel tanks. And these guys were no fools, or so I thought. One of them pulled up next to me, waggled his wings as if telling me to form up, then pulled ahead. I had forgotten to turn on the gunsight or arm the guns, but when I did I knocked him down. My wingman, Moe Fisher, blasted one off my tail, and we headed for the deck to protect the bombers. I nailed another one real quick, but I flew through the explosion. I saw another skimming the water trying to get away, so I chased him. I was closing on him when a little voice warned me, and I pulled away. There was his wingman. The lead Jap had been the bait, and I had almost fallen for it. I turned into the second Zero head-on. We closed, firing on each other, and I won. The first Zero had disappeared, but I saw another coming head-on at a lower altitude, and I got him, too. As I tried to milk my remaining fuel, I saw a Corsair-just over the water and vulnerable-being attacked by two Zeros. The Marine aircraft was damaged, with oil all over the windscreen, and was losing speed. I attacked the nearest Zero, and as I fired he pulled up. I tried to follow, still firing, and he broke apart, but I stalled out. I recovered enough to hit the second Zero, and then I calmed down. The adrenaline rush of air combat is something that you can’t explain. I did not see the Corsair again or even know who was in it, but Bobby Ewing was the only loss we had, so it must have been him. There was no way I could make it back to base, so I headed for Munda, where I made a perfect dead-stick landing-no gas at all.

AH: Unlike what we’ve come to expect from the TV show, that was not a typical mission, right?

Boyington: Far from it. I scored five kills in one mission, and I would never do that again. Most of a combat pilot’s missions are mundane and almost boring, especially when you are beginning to win a war and you outnumber the enemy, although that would not really be the case until after I was finally bagged.

AH: Did the success of the unit help you out with your superiors at all?

Boyington: Everyone except Lard. He had heard about the drinking problem in China and Burma, so he placed me under parole of sorts. I was not to drink, and if I did it was to be reported. I still had a few, and Lard found out about it and placed me in hack. Unless I was flying I could not socialize. Do I need to tell you whether or not I obeyed that order?

AH: No, I don’t think so. Did the Black Sheep’s success garner any interest from superiors?

Boyington: Shortly after our first great success, I was invited along with my executive officer to the new commander’s office. He offered me a drink, and I was suspicious. He assured me that he was not part of Lard’s program, that I was safe. He even pulled out a copy of the order signed by Lard and tore it up. Well, we soon got stuck with escort missions galore. We did not engage a single enemy plane in weeks, although the guys at Munda were having a hell of a time. They were the first line of defense, and the Japs never got through them to reach us. We finally got creative, especially when the Japs began to identify me over the radio. They would ask my position in plain English, although they were fooling no one. One day I gave them a lower altitude as a response, and sure enough there came 30 Zeros. We caught sight of the Japs heading to 20,000 feet to intercept us, but we were at 25,000, and we peeled over into them. We screamed into the enemy formation head-on, and I think everyone got a hit or kill on the first pass. My first hit blew up, and a second plane I hit began to smoke and the pilot bailed out. I continued to pull around and caught a third Jap, and he went down. We had done good work, and I was proud of my boys. We had scored 12 kills without a loss.

AH: You had a few close calls yourself, didn’t you?

Boyington: Sure, but most of my problems were caused less by the Japanese than by our own ground crews. I scrambled with the squadron to intercept some inbound enemy bombers, and in the middle of a dogfight with escorting Zeros my engine died. I took a dive for the deck with a dozen meatballs on my ass. If it were not for the Navy pilots in a [Grumman F6F-3] Hellcat unit I would not be here now. I headed back to base without fuel. My plane had not been refueled after the previous mission, and I was about as pissed as you could be without committing murder. I had had a perfect chance to score some bomber kills, and it was gone. Another time I took off and the engine cowling tore loose, forcing me to return to the strip. Upon landing, I jumped into another Corsair and continued the mission, but without any success. I never scored a bomber kill. But we did destroy a large number of aircraft on the ground during fighter bombing and strafing missions.

AH: You met Admiral William Halsey and Chesty Puller. What did you think of them?

Boyington: Halsey and some other brass came to see me once at Munda, and I liked him. He didn’t appear to be the kind of man who really got on your ass about small things. I could relate to him, like Stilwell. Now Chesty, on the other hand, was a completely different animal, sort of like me 10 times over and on steroids. He was one hell of a Marine, the best who ever served, probably. He’s one of those few even I would do anything for, because he cared about his men and he loved the Corps.

AH: What happened the day you were shot down?

Boyington: Well, first of all, contrary to what I have heard over the years, I was stone-cold sober the day of the flight, which was January 3, 1944. Everything started out wrong that day. My plane was down, so I had to take another. I led the squadron on a fighter sweep to Rabaul, the bastion of Japanese naval pilots. We were at 20,000 feet. Everyone knew that I was expected to beat Joe Foss’ record of 26 kills, since he had just tied Eddie Rickenbacker’s score not long before. Even Marion Carl allowed me the opportunity to lead several of his flights, giving me the chance to increase my score. This was because I was due to be rotated out due to age and longevity. At this time I had 25 [actually 21], and Rabaul was just about the best hunting ground you could imagine. Well, to make a long story short, my wingman George Ashmun and I were looking for trouble, and George told me just to focus on getting the kills-he would take care of my six. Soon we were surrounded, and I scored three, but George was overwhelmed, and I was trying to help him when I was also hit. I could hear and feel the shells striking the armor plate and fuselage. I remember my body being banged around, then suddenly I had a fire in the cockpit. The engine and fuel line had been shot up. I was at about 100 feet above the water, so I did not have much choice. George had already been flamed and hit the ocean. I was apparently going to share the same fate, so I managed to kick out of the Corsair and pull the ripcord, letting the slipstream open the canopy. I hit the water, but it could just as well have been pavement. I managed to inflate my rubber raft, but my Mae West was shot full of holes and was no good. I assessed my injuries, saw that I was beyond screwed up, and hoped that I would be rescued. This wish to be rescued really became urgent once four Zero pilots began taking turns strafing me in the water.

AH: You were rescued-but not by friendly forces, right?

Boyington: Yes, a few hours later a Jap submarine on the way to Rabaul surfaced and collected me. I dumped everything I had that was of any military value over the side.

AH: How bad were your wounds?

Boyington: Well, I nearly lost my left ear, which was hanging in a bloody mess. My scalp had a massive laceration, my arms, groin and shoulders were peppered with shrapnel, and a bullet had gone through my left calf. I had seen better days. Luckily the sub crew tried to take care of me. They were very humane, and I wondered if this was the type of treatment I could expect in the future. One of the crew spoke English and assured me that I was going to be all right.

AH: What preparation had you been given in training for capture and interrogation?

Boyington: None. We never even considered the possibility. I think this was a great mistake on the part of the military. I was totally unprepared. I believe that even if we had been prepared for captivity and interrogation, we would have still been unprepared to some extent, since we would have trained our men in the Occidental method of psychological warfare and interrogation resistance. All of this effort would have been wasted once we were captured by the Japs, or later the North Koreans, Chinese or Vietnamese. Their mind-set and perspective are completely different, and we just don’t understand it.

AH: What was your imprisonment like? Do you hold a grudge against the Japanese for the way you were treated?

Boyington: Well, it was hard. We were beaten on occasion, and questioned even about the most ridiculous BS. Most of the guards were pretty brutal, but once you learned how to out-think them you could get by. There was one particular interpreter who had been educated in Honolulu, and he was very important, since he effectively saved not just my life but the lives of others as well. Then there was this old lady in Japan whom I worked for in the kitchen at the camp. By the time I got there I was down 60 or 70 pounds and not looking so good. She took care of me, and I owe her as much as anyone. However, despite the beatings and starvation diet, I probably lived as long as I have due to the fact that 20 months in prison prevented me from drinking. The one exception was New Years Eve 1944, when a guard gave me some sake. Another important person was a Mr. Kono, a mysterious man who spoke English and wore a uniform without rank. He perhaps did more to save American lives than anyone else. As far as holding a grudge, no. That would be silly. There are good and bad people everywhere. The Japanese civilians who had been bombed out and were always around us showed us respect, not antipathy. Many of them went out of their way to help us at great risk to themselves, slipping us food. When I think about how the Japanese civilians treated us as POWs in their country, I can only feel very ashamed at how we treated our own Japanese Americans, taking their homes and businesses and placing them in camps.

AH: Did you get any news about how the war was going while you were in captivity?

Boyington: Well, we were kept updated on the war news, usually by friendly guards who would tell us what was going on. Other news we learned by listening to the guards. I picked up the Japanese language pretty quickly, and I could understand many phrases and keywords. New prisoners were also a great source of information. We knew the war was going badly for Japan, and in February 1945 we saw a massive raid on Yokosuka from our camp in Ofuna. I was informed by a Japanese man that Roosevelt had died and that Germany had surrendered. Later we were moved from Ofuna to a real POW camp. This was a great thing, because we were up to that point below prisoner status. At least when we were POWs our families would know we were alive and reasonably well. That also meant it would be more difficult for the Japs to just execute us with no one asking questions, which was always on our minds. When we were moved to a more solid structure I felt a little better, especially once the Boeing B-29 raids picked up the pace. We would watch them at high altitude, sometimes engaged by a Jap, but they just gave us so much hope. However, once the bombing picked up, we were placed on rubble-clearing details, digging tunnels in the hills. This was near Yokohama. One bit of irony was when a guard told me about a single bomb that had been dropped on his home in Nagasaki. He was speaking in Japanese, so it was difficult to understand. I could only make out that the city had been destroyed by a single bomb. This was beyond my comprehension, and it was not until after I was released that I found out it was true. I also found out from a guard that the war was over. The guards almost to a man got drunk at the news, something I was very familiar with. What bothered us was the fact that some were openly discussing killing us, which made us a little uncomfortable. The commanding officer came down the next day and gave us vitamins and new clothes, preparing us. Six days later I was standing in front of the Swiss Red Cross in new quarters and very clean. A few days later B-29s were dropping clothes and food to us, and a few guys were killed by being hit. Soon the Navy landed with the Marines, and we were able to leave. We went to the hospital ship Benevolence, where the medical staff checked us all out. After the disinfectant and shower, I had the best meal in memory, ham and eggs. Some of the guys just could not take that diet after the pathetic diet of rice and stuff we had lived on.

AH: How soon did you get swamped by the media?

Boyington: Almost immediately, on the ship. I really didn’t have much to say, except hello to my family. After I was cleared, I flew from Tokyo to Guam, Kwajalein, and Pearl Harbor, headed Stateside. Major General Moore met me at Pearl Harbor, and I can’t explain the feeling I had on seeing my old friend and benefactor. He gave me the use of his quarters, car and driver, and that was great. I had decided to change my ways, accept my fate and clean myself up. I felt that if the nation was going to honor me as a hero, I should honor the nation by acting like one, or at least looking like one. You know, I think that the only reason the Corps released all the glowing heroic junk about me was because they thought I was dead. It took a few weeks after I returned for anything to be forwarded or for any of the public relations brass to get in touch with me. But, as I have been quoted as saying, show me a hero and I will show you a bum.

AH: I believe you met some of your old squadron mates upon returning. Tell us about that.

Boyington: That was in San Francisco. Twenty of the guys had shown up, remembering that we had planned a party six months after the war was over, and they decided to have one then and there. We did, but after so much time I could not drink like I used to. The best thing was the gift they gave me, a gold engraved watch. Ironically the party was covertly covered by Life magazine, and the pictures were impressive. I suppose it was a good thing that they were never around in the South Pacific when we had our parties then. The morality meter would have spun off the scale.

AH: How did things turn out for you after the war?

Boyington: Well, for PR purposes I did these war bond drives with Frank Walton, the S-2 [Intelligence officer] of the squadron. We talked to people all over the country, but I still had not received my back pay. I was living off the generosity of others, broker than hell. When we went to Washington, D.C., I received the Navy Cross from General Archibald Vandergrift, the commandant. Then I went to see President Harry Truman, who gave me the big one. After that it was a New York ticker-tape parade, then more traveling. Later I was retired due to wounds, but that only made things worse. I could not find a job until I began working as a wrestling referee part time. My second wife, Franny, kept me out of too much trouble, although nearly every place I went there was some cop for whatever reason waiting to pick me up, especially after I had been in a bar. They would call the press just to get their names in the papers at my expense. Later I was a beer salesman for a few years; it seemed like poetic justice in a way. It made me sober up again after falling off the wagon.

AH: The later years seem to have been pretty good to you.

Boyington: Well, I sobered up after a bad crash-and-burn session once. I think that Steve Cannell and the others who wanted to create the movie and television series did a lot to help me maintain perspective. We still have the reunions of the AVG and Black Sheep, and Dick Rossi handles all of the AVG gatherings. Those are held here in California, so they are easy to get to.

AH: How do you feel about the wars that followed WWII, and the military today?

Boyington: Well, first of all, I don’t think a man-let alone an officer-could get away with the things we used to pull back then, especially me. And that is probably not a bad thing. The wars that followed were pretty much like any other. I could not respect a man who walked away from a fight where his flag was at stake. However, I think that our government should be more particular as to which wars we get involved in. The military today is high-tech and all volunteer. I think that as long as we never lose focus on what’s important, we will be all right. I would hate to think that American lives could be easily thrown away on a bad policy decision. We just have to have faith in our government, which is not easy, and faith in the military. If the government goes to war, then let the military fight it. That is how America will stay great.

This article was written by Colin Heaton and originally published in the May 2001 issue of Aviation History. For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!