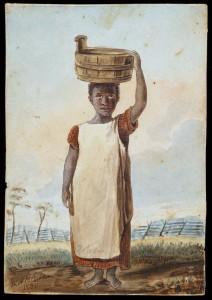

Nine years ago, the Alexander Gallery in Manhattan acquired several items once owned by Confederate General JEB Stuart. Among them was a small watercolor portrait painted by Mrs. Robert E. Lee. Measuring only four inches wide and five and three quarters inches high, Enslaved Girl depicts a young girl in a red dress and white apron, balancing a tub on her head. Though she is small, female, and vulnerable, her calm expression and her stance convey an unmistakable air of strength and self-possession. Behind her lies a split rail fence and a line of trees. Someone, perhaps Mrs. Lee herself, wrote the word “Topsy” in pencil on the girl’s apron.

Nine years ago, the Alexander Gallery in Manhattan acquired several items once owned by Confederate General JEB Stuart. Among them was a small watercolor portrait painted by Mrs. Robert E. Lee. Measuring only four inches wide and five and three quarters inches high, Enslaved Girl depicts a young girl in a red dress and white apron, balancing a tub on her head. Though she is small, female, and vulnerable, her calm expression and her stance convey an unmistakable air of strength and self-possession. Behind her lies a split rail fence and a line of trees. Someone, perhaps Mrs. Lee herself, wrote the word “Topsy” in pencil on the girl’s apron.

Painted in 1830, the year before the then twenty –three- year- old Mary Anna Randolph Custis married her distant cousin, Enslaved Girl was valued at $400,000 and sold to the museum at Colonial Williamsburg for an undisclosed sum.

The only living child of George Washington Parke Custis and Mary Lee Fitzhugh Custis, Mary Anna grew up at Arlington, the family home her father built as a memorial to his step-grandfather, George Washington. She was educated by a cadre of private tutors, and encouraged in her artistic pursuits by her father, himself a painter, poet, and playwright.

Along with the 1100 acres overlooking the Potomac River that Mr. Custis inherited from his father were a number of slaves who lived at Arlington and at the other Custis properties in Virginia, Romancoke and White House, where in 1759 George Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis.

Records indicate that the enslaved population at Arlington hovered at around sixty men, women, and children, most of them families. Among them was the Norris family. Leonard and Sally Norris, said to be favorites of Mrs. Custis, had four children: Selina, Wesley, Mary, and Sally.

Selina, born in 1823, was taken into the Custis household at an early age to train as a housekeeper. As an adult, she became the head housekeeper at Arlington and served as Mrs. Lee’s personal assistant.

Plagued by crippling arthritis for most of her adult life, Mrs. Lee grew increasingly dependent upon Selina and others to care for her and her brood of seven boisterous children. The two women developed such a close bond that when Mary and her daughters fled Arlington at the start of the Civil War, she trusted no one but Selina with the keys to her home.

Selina, who by that time had married Thornton Gray, an enslaved man at Arlington, grew alarmed when Union soldiers began looting the house, making off with furnishings, silver, and other items that had once belonged to George Washington. She confronted their commanding officer, General Irvin McDowell, to demand an end to the thievery of “Miss Mary’s things.” The general moved the rest of the items to the U.S. Patent office where they remained until after the war. Today, Selina Gray is remembered as the “savior of the Washington treasures.”

The discovery of the Enslaved Girl portrait presents an intriguing question. Is Selina the girl in the painting? According to the Colonial Williamsburg description, “likely the subject was one of the Custis slaves though her name is unknown.” But several known facts raise the possibility that it could be Selina Norris Gray.

The first is the date. In 1830, Selina would have been seven years old, the approximate age of the girl in the painting.

Secondly, Mary Anna and her mother strongly believed in preparing the Custis slaves for eventual emancipation and to this end, they taught the children at Arlington to read and write. Perhaps Mary decided to paint one of her most able students, a child with whom she had a close and ongoing relationship both in the household and in the little schoolroom at Arlington.

What is to be made of the word “Topsy” added to the portrait? Topsy is a character in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was first published in its entirely in 1852, the same year Mrs. Lee joined her husband at West Point, where he served as superintendent from September of that year until March of 1855. As a proponent of emancipation, Mrs. Lee undoubtedly read Mrs. Stowe’s anti-slavery novel (which became the best-selling novel of the 19th century, its popularity eclipsed only by the Bible). Perhaps “Topsy” called to her mind one of her own Arlington slaves. One for whom she had great affection and knew intimately enough to paint in such fine detail.

What is to be made of the word “Topsy” added to the portrait? Topsy is a character in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was first published in its entirely in 1852, the same year Mrs. Lee joined her husband at West Point, where he served as superintendent from September of that year until March of 1855. As a proponent of emancipation, Mrs. Lee undoubtedly read Mrs. Stowe’s anti-slavery novel (which became the best-selling novel of the 19th century, its popularity eclipsed only by the Bible). Perhaps “Topsy” called to her mind one of her own Arlington slaves. One for whom she had great affection and knew intimately enough to paint in such fine detail.

It is believed Mrs. Lee gave the portrait to JEB Stuart while he was a cadet at West Point. It then disappeared for more than a hundred and fifty years.

Historical inquiry demands a constant reassessment of what we think we know. With each new discovery we are called to rearrange the puzzle pieces of the past into a new and more complete picture. Perhaps new scholarship will one day shed more light on the Enslaved Girl. Until then, her identity and her story remain a tantalizing mystery.

Dorothy Love is the author of Mrs. Lee and Mrs. Gray: A Novel (HarperCollins June, 2016)