By late 1942, the Americans were sure they had the equipment and the doctrine to win the European air war and, U.S. Army Air Forces commander Henry “Hap” Arnold liked to think, the whole war in Europe. But the fresh new VIII Bomber Command was off to a shaky start. Most of the pilots and crewmen were little more than raw recruits, and due to poor weather, equipment shortages and failures, and sheer inexperience, they weren’t flying many missions. Just herding them into formations was a challenge. When they did fly, they weren’t hitting targets, even with the vaunted new Norden bombsight. And their B-17s were being picked off by German aces and flak, especially once they got beyond Allied fighter cover.

The commander of the fledgling 305th Bomb Group, however, was eager to take on the massive job of tactical problem solving. Thirty-six-year-old Lt. Col. Curtis LeMay was one of America’s top pilots and navigators, a nuts-and-bolts man who had always loved working on cars and ham radios. Combining a tinkerer’s natural pragmatism with a lead-from-the-front command style, LeMay happily challenged military doctrine, and took apart his group’s tactical problems one component at a time.

As he would later explain, “I preferred to fly in the left-hand seat, but…I flew as co-pilot on occasion; and then maybe the next mission I would take the flight engineer’s job…. Sometimes I would go around and visit the bombardier and navigator or radio operator, or one of the gunner’s positions. It was my purpose in so doing to learn whether there were any procedures which were being done wrong—whether there were basic improvements which could be made in the performance of the men flying these positions. I think it did a lot of good. I was able to find places where the work could be improved by the introduction of new practices.”

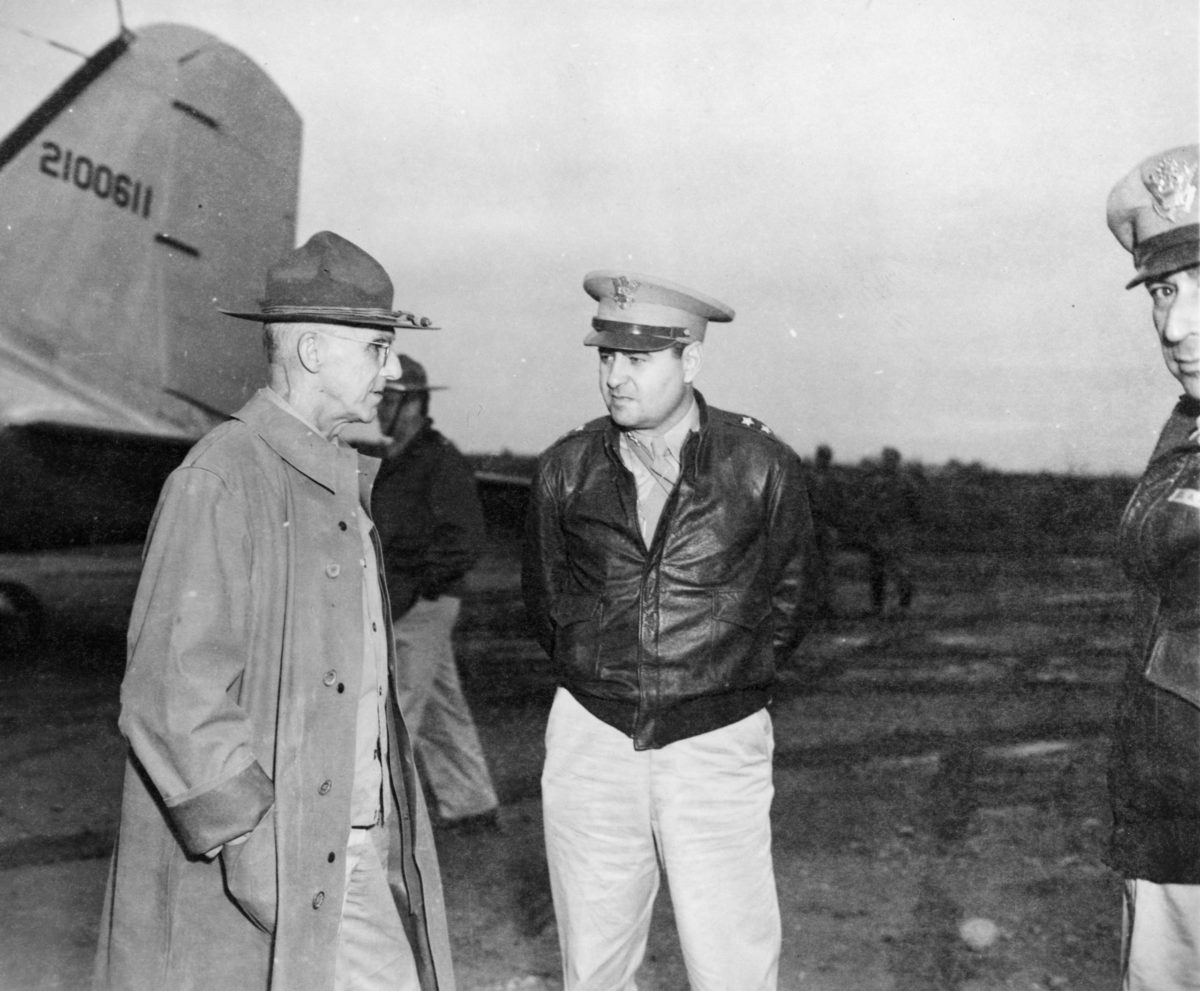

LeMay maximized the B-17’s efficiency, devising in a matter of months several pivotal innovations that improved the accuracy and survival of his bomber crews and quickly became standard practice for the entire Eighth Air Force. Hap Arnold concluded that LeMay was made to order for impossible jobs, which became his stock-in-trade for the rest of the war. Indeed, the cocksure, cigar-chomping air chief became one of America’s best-known field commanders. Abrasive, taciturn, bullheaded, and single-minded, he drilled his flyboys to the point of distraction and delirium and focused solely on his grail: target destruction. “In war,” LeMay liked to say, “the object is to destroy more of the enemy’s capability than he does of yours.”

Seeing the world in black and white was both a key strength and a flaw. As a wing commander, that trait made him stand out: personally fearless, he was willing to share his men’s risks while sending them into deadly situations, and then to relentlessly parse their performances as simple ratios between target destruction and losses. Later, it helped ensure that the achievements he ranked among his greatest—such as his unapologetic role in commanding the firebombing of 67 Japanese cities— would remain controversial. “A soldier has to fight,” he later averred. “We fought. If we accomplished the job in any given battle, without exterminating too many of our own folks, we considered that we’d had a pretty good day.”

Curtis Emerson LeMay discovered self-reliance soon after his birth in 1906. His parents, raised by Ohio dirt farmers, were American drifters. By the time LeMay was two, they had moved a dozen times, and the boy ran away from home regularly. Yet he believed that “if you grow up amid the confused ignominy of the very poor and insecure, and if you are sufficiently tough in spite of this, poverty can prosper you.” The oldest of six children, LeMay never stayed in any school for long and made no close friends. Taking his own counsel became a lifelong habit.

So did tinkering. Young Curt loved to play with gadgets and, at five years old, he chased the first flying machine he saw. When it flew off, he stomped home in angry tears, then turned to crystal sets and, later, cars. Machinery never daunted LeMay. He built and rebuilt guns, fishing tackle, and sports equipment. He loaded his own ammo; if it didn’t work he only had himself to blame. He read historical novels, biographies, and travel books, but self-reliance and tinkering shaped his analytical bent.

College at Ohio State University was a tangle of work, study, and ROTC training, which he hoped would open the door to training as a flight cadet with the army. In 1928, he wangled his way into the U.S. Army Air Corps and in 1933 went to Langley Field in Virginia to study a new art: applying celestial navigation to flying. There he encountered the “Black Box,” an early celestial computer whose cranks and counters solved the celestial triangle far faster than working through logarithmic tables and trigonometry. It would guide the second lieutenant to his future.

After LeMay married in 1934, he joined the 6th Pursuit Squadron in Hawaii as an engineering officer and navigation instructor, the latter on his own initiative: “What the Air Corps would need…was more and more men specifically trained for navigation—not those who had just dabbled in it.” It was a shrewd insight. He replaced training flights that circumnavigated Oahu with roundtrips to Bird Island, about 150 miles west— despite navy objections to the Air Corps flying over water and his commander’s concern about lack of accurate charts. LeMay’s retort: “Our navigation is precise enough.” It was.

By 1936 LeMay’s navigational studies got him speculating about the potential of long-range flying: “Who would go deep into the enemy’s homeland, and thus try to eliminate his basic potential to wage war? Bombers, nothing but bombers.” He got assigned to the 2nd Bomb Group at Langley Field, where he was ordered to open a navigation school and met one of his life’s great loves, the B-17 Flying Fortress. This plane, he insisted, even smelled different. A true strategic bomber, the B-17 crystallized LeMay’s notion of air power. But statistical survivability also played its part in LeMay’s romance: this state-of-the-art four-engine aircraft had 6,500 times the reliability of a single-engine plane and 27 times that of the twin-engine B-10 or B-18. It also had 5 defensive gun positions versus 3 in two-engine jobs, and eventually bristled with 7 to 9 positions and 10 to 13 guns.

Langley shifted LeMay’s career into high gear. He met mentors like Maj. Gen. Frank Andrews and Lt. Col. Robert Olds, who demanded that his men be ready to fly and fight at any moment, and insisted that “anything which mitigated against that efficiency was not tolerated.” Olds flew the Air Corps’ first B-17 back to Langley; by June 1937, his group had seven Flying Fortresses— and the Norden bombsight. (For an illustrated take on the sight’s efficacy, see “Weapons Manual,” page 68.) Amid endless practice sessions, the future was coming into focus.

Still, the veteran pilots didn’t have much faith in navigators. LeMay changed that almost single-handedly. First came the 2nd Bomb Group’s joint exercise with the navy, the “bombing” of the battleship Utah by Air Corps planes in August 1937. Despite the navy’s twice giving the wrong position report (in an attempt to back up their belief that no bomber could sink a battleship), lead navigator LeMay found the ship. But the navy had the results of the exercise hushed up, leaving Air Corps men like LeMay bitter.

The next breakthrough came in early 1938, when six B-17s flew to Buenos Aires, Argentina; Lima, Peru; and Santiago, Chile, invoking the Good Neighbor policy while flexing Monroe Doctrine muscle. LeMay was lead navigator. These were seat-of-the-pants days: there were no Andes weather stations to rely on, only National Geographic Society maps, and the crews had their first encounters with anoxia, which had them reading altimeters and ground speed incorrectly. “We were,” LeMay said, “pioneers in covered wagons.” But these first Fortresses showed their potential. “We proved that we could fly for seven-and-a-half hours, visit an objective, and come back to our base in another seven-and-a-half hours,” he recalled. “It meant that, with a reduced gas loading, we could carry bombs on a shorter trip.”

There were other triumphs of navigation and endurance such as finding the Rex, an Italian liner, 755 miles away in the Atlantic, and making a larger circuit of South America. The lieutenant made captain in 1940. War preparations were shaking up the peacetime military—and the Army Air Corps, encouraged by president Franklin Roosevelt’s public calls for the production of thousands of planes, jockeyed against the army and navy for bigger pieces of the coming war and its ballooning budgets. In March 1941, when LeMay was promoted to major and became a squadron commander in the 34th Bomb Group, he wondered when and how—not if—the United States would be drawn into the global conflict.

The war started for LeMay shortly afterward, with a call from Canada. A group of Army Air Corps officers, including LeMay, ferried military brass, diplomats, and journalists across the Atlantic in B-24s, aircraft so new that LeMay’s transoceanic flight was his maiden voyage in one. Then came Pearl Harbor. After bouncing around in the crazed days that followed, LeMay started training raw recruits of the 305th Bomb Group on B-17s at what is now Edwards Air Force Base. “Drill, drill, drill” was his mantra, and it earned him the nickname “Iron Ass.”

In late 1942, LeMay shepherded his semitrained flyboys across the icy North Atlantic into the near-chaos of the frantic American buildup. Stationed at Chelveston, England, the 305th had an invaluable engineering officer, Ben Fulkrod, who hustled or manufactured desperately needed spare parts. LeMay’s encouragement of Fulkrod’s talent for aircraft maintenance was one of his typical do-it-yourself masterstrokes: no one else had a Fulkrod. Though planes and parts were overwhelmingly routed to North Africa, and his aircraft strength often dipped below 50 percent, LeMay kept his group flying more than any other.

And almost immediately, LeMay began producing glimmers of what Arnold desperately wanted: proof that American air power in Europe would be decisively deadly. That turned out to be true. But it also proved deadly for American airmen. The Eighth Air Force logged 26,000 fatalities—more than the Marine Corps’ entire tally for the war—plus 28,000 wounded and taken prisoner. LeMay was a major reason the gruesome statistics weren’t even higher as the U.S. Army Air Forces struggled to fulfill the mission against Nazi Germany—and, not coincidentally, prove American military doctrine and technology superior to British.

American airmen like Hap Arnold and Jimmy Doolittle had come into the war dismissing British nighttime area bombing— overseen by RAF Air Chief Marshal Arthur “Bomber” Harris and approved by Winston Churchill—as wasteful due to its inherent inaccuracy and, because cities were the usual targets, fraught with collateral civilian damage. Secretary of War Henry Stimson and President Roosevelt strongly shared that viewpoint. Armed with the Norden bombsight, American air doctrine postulated precision daylight bombing.

But daylight bombing had its own challenges. The increased visibility increased the bombers’ vulnerability. To minimize the added exposure to antiaircraft fire, they were making short, abrupt runs at their targets. Analyzing his group’s data, LeMay quickly realized this made accurate targeting a matter of luck: more than half the bombs dropped were falling wide of the mark. Only a few were actually hitting the targets. He also deduced that the evasive jinking maneuvers his pilots used en route to their targets gave the B-17 no greater survivability against German flak. The answer seemed obvious to him: he drilled his men on seven-minute-long steady approaches, which they considered suicidal.

To provide extra protection and increase firepower, LeMay configured his B-17s into a new formation that came to be known as the combat box. Since each Flying Fortress bristled with guns, LeMay’s box massed and stacked them in a tight grouping. That maximized each bomber’s ability to protect itself and others from German fighters, a critical tactic since no Allied fighters could penetrate far beyond France.

To prove his point, LeMay put himself on the line, leading a November 1942 mission over Saint-Nazaire, France. “It was the first time in the Army Air Forces’ European Theater experience that a large formation of heavy bombers had ever approached a target without using evasive action in an attempt to avoid the enemy’s ground-to-air shellfire,” he recalled. “I led that one, so I…suffered and wondered right there.”

He didn’t have to wonder long: on that bombing mission, the 305th’s first, they hit twice as many targets as any other group without losing a single bomber. In the missions that followed, the 305th continued to lead in target destruction and, although suffering some losses, still had fewer than other groups. As Hap Arnold pressured Eighth Air Force commander Ira Eaker for results, LeMay’s tactical innovations gradually became standard.

Combat losses climbed sharply beginning in January 1943, however, when the Eighth Air Force began flying missions over Germany and faced ferocious opposition; LeMay’s men paid with an attrition rate of between 4 and 8 percent. German defenses proved so formidable that a crew’s chance of surviving 12 missions was less than 50 percent. Airplanes and crews couldn’t be replaced fast enough; one dire projection warned Eaker that there would be one B-17 left by March. The “arsenal of democracy” desperately needed time to manufacture and distribute materiel for a cross-channel invasion and a multifront war; American lives were buying that time. Meanwhile Arnold, fighting to make his service’s reputation, and to expand its power and budget vis-à-vis its sister services, pounded Eaker with directives and complaints.

Until 1944, when replacement planes, parts, and crews finally kept pace with losses, the Eighth Air Force operated on a wing and a prayer with make-do compromises not far from Catch-22: by combining units to maximize resources—as when Eaker’s staff melded the 305th with another group to create the 102nd Combat Wing, with LeMay in charge—or by increasing the number of missions crews had to fly. Arnold kept upping the pressure: belittling Eaker’s men, commanders, and commitment; evading questions about replacement crews and materiel; and pushing for new blood like LeMay, who was soon commanding the 3rd Bomb Division.

While he waited impatiently for the rank-stingy Arnold to OK his promotion to major general, LeMay helped execute one of this phase’s culminating horrors, the Schweinfurt-Regensburg mission of August 17, 1943. Regensburg, the 3rd Bomb Division’s target, was a center for Messerschmitt production. The plan from Arnold’s Committee on Operational Analysis called for B-17s to cross Europe, drop their bombs, and land in North Africa. It was breathtakingly complex by the era’s standards, and, as it turned out, beyond the Allies’ tactical and operational capabilities. LeMay led 146 B-17s from England, hit Regensburg, and made it to Tunisia. There he discovered supplies and backup were nonexistent. He also discovered the operation was far more costly than he’d seen from the lead plane: 24 bombers lost, most of the rest damaged. (Losses to other divisions brought the toll to 60 bombers.)

The results were at best a wash. In September German production was continuing apace, and the Eighth Air Force had recovered enough to send 407 bombers against Stuttgart, where bad weather cost them effectiveness, and a lack of fighter cover cost 44 planes. After an even more disastrous week in October, ending with the October 14, 1943, raid on Schweinfurt—in which another 60 bombers were lost, with LeMay’s old outfit, the 305th, losing 13 of its 15—the Allies curtailed bombing runs beyond fighter cover. Arnold finally promised Eaker he would speed fighter development and deploy more of them to England. In December 1943, the first long-range P-51B Mustangs began escorting American bombers, and missions deep into Germany resumed the following month.

By then a brigadier general, LeMay owned a reputation as an innovative thinker who was brusque to the point of rudeness, dedicated and ambitious, and extremely knowledgeable about mechanics and electronics. As Allied propaganda spun the European war’s manifold problems, he also acquired PR value: Eaker tapped him as an unwilling “Bond Show Bill” for a month in the United States. Then it was back to Europe: for a campaign called “Big Week” in February 1944, when 3,300 Eighth Air Force bombers hit the German aircraft industry; the first bombings of Berlin; supply drops to resistance fighters; and interdiction bombing runs before D-Day. On March 3, 1944, Arnold finally made LeMay a major general. By D-Day, the Luftwaffe’s fighter component was effectively neutralized. The Eighth Air Force had taken a quantum leap toward destroying the Nazi industrial infrastructure—and little would stop the grisly, crucial, and inexorable process from here on.

Just after D-Day, Arnold tapped his can-do star to steer his troubled brainchild, the B-29. Born of the early fear that England would fall and the United States would have to bomb Europe from homeland bases, the Superfortress’s problems were stoked by its hyper-accelerated development schedule, which reflected the now-screaming need for a bomber that could reach Japan’s home islands—and make it back. So the usual procedure—testing models, discovering kinks, sending engineers back to the drawing board—was tossed. By mid-1944 the B-29, with a price tag of $3 billion, hovered on the brink of disaster. Fuel tanks flamed; the Wright R-3350 engines overheated, swallowed valves, caught fire; cylinder heads burned out; ignitions were faulty. As LeMay put it, “B-29s had as many bugs as the entomological department of the Smithsonian Institution.”

Characteristically insisting he had to check out the new aircraft himself, LeMay learned to fly the B-29 in a program set up just for him. On August 29, 1944, he landed in Kharagpur, where he was to take over leadership of XX Bomber Command and its B-29s. There he confronted a mountain of a nightmarish operation, perhaps appropriately called “Matterhorn.” LeMay’s XX Bomber Command was to fly fuel and supplies from India on a dangerous route over the Himalayan Hump to Chengdu, in Szechuan Province, where the Chinese had built an airfield large enough for B-29s to take off and land. There they would stockpile materiel for bombing runs against Japan. But LeMay soon realized that stocking enough fuel reserves for just one mission against Japan required seven B-29 flights. And airplanes went down regularly over the Hump and busted up on Indian and Chinese landing strips.

So LeMay replicated his European tactics—intensive training, combat box flying, the whole magilla. Combining diplomacy with survivability, he negotiated support systems for downed flyers with Chinese leaders Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong, who had toiled at carving out a B-29 landing field himself. But even LeMay could squeeze at best only four missions a month from the operation. One, however, proved a harbinger.

Maj. Gen. Claire Chennault, commander of the China-based Fourteenth Air Force, convinced Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer, the theater commander, that an incendiary raid on a Japanese supply center in Hankow, China, would seriously disrupt enemy operations. On December 18, 1944, at Wedemeyer’s “request,” LeMay sent 84 Superfortresses to Hankow, while Chennault ordered in 200 additional planes. The target area burned spectacularly for three days, and Chennault’s staff concluded the city was “destroyed as a major base.” This confirmed what air force analysts had long suspected: Asian cities, made primarily of wood and paper, would flare and collapse under firebombing.

Around New Year’s Day, LeMay was ordered to Guam. LeMay’s XX Bomber Command and its mission would be absorbed into XXI Bomber Command, his new command. He would be field commander for strategic air operations against the Japanese home islands. (There was one key exception: LeMay would provide support for, but not run, the atomic bombing missions.) The tropical climate in Guam made him switch from smoking pipes (which got moldy) to Cuban cigars. The cigar clenched between his teeth became a trademark while LeMay battled his old foe the navy, which was building tennis courts, rehab centers, and dockage facilities—anything, he growled, but air bases.

Aside from the already-long list of B-29 problems that LeMay had to contend with, 200 mph high-altitude jet streams and Japanese weather were limiting visual bombing to just three or four days a month. (Desperate for forecasts, he tried breaking the uncooperative Russians’ codes.) After six weeks of missions, and mounting veiled threats from Washington, he concluded that the tactics he had developed in Europe were worthless against Japan. The bombers he had sent from China scored hits near their targets only 5 percent of the time; despite repeated drilling, those flying from the Marianas didn’t fare any better.

Hap Arnold—battling by then not only the Axis, but growing home front discontent and the army and navy, which were both clamoring for “his” B-29s—needed results to save his brainchild, and his air force’s dreamt-of future as an independent service. His Joint Targeting Group insisted incendiary bombs would be especially effective against Japanese cities. So daylight precision bombing began to give way to nighttime area bombing—the British doctrine Americans had so reviled.

To up the B-29’s bomb capacity, as Arnold kept demanding, LeMay again boldly flaunted conventional wisdom. His analysis told him there was little low-altitude flak over Japan, and that the enemy’s night fighters were negligible risks. He stripped 325 B-29s of defensive guns and gunners to lessen their weight, allowing an increase in bomb and fuel loads; then he filled them with incendiary clusters, magnesium bombs, white phosphorus bombs, and a new product called napalm, and ordered them to fly over Japan at night at 5,000 to 7,000 feet instead of 30,000, which had his crews gnashing their teeth. “We might lose over three hundred aircraft and some three thousand veteran personnel in this attack,” he wrote. “It might go down as LeMay’s Last Brainstorm. But I didn’t think so. If I had, I wouldn’t have ordered the operation to be flown as it was flown.”

The night of March 9, 1945, LeMay’s reconfigured B-29s took off. In three hours, they dumped tons of incendiaries on Tokyo, killing some 80,000 civilians and destroying the homes of a million others. The crews in the last aircraft reported being assaulted by the stench of burning flesh. Unlike in Europe, LeMay waited behind at HQ, grounded because he was one of the few to know about the atomic bomb and couldn’t risk capture and interrogation. When the planes taxied in, only 14 were lost. “Eighty-six percent of them attacked the primary target,” LeMay later wrote. “We lost just four-and-three-tenths per cent…. Sixteen hundred and sixty-five tons of incendiary bombs went hissing down upon that city, and hot drafts from the resulting furnace tossed some of our aircraft two thousand feet above their original altitude. We burned up nearly sixteen square miles of Tokyo.”

“Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay,” the New York Times reported, “declared that if the war is shortened by a single day, the attack will have served its purpose.” With Roosevelt and then Harry Truman facing varying horrific estimates of American casualties in an invasion of Japan, LeMay was not alone in that feeling.

The attacks continued, slowed only by bad weather and resupply difficulties. By April, LeMay wrote, “I feel that the destruction of Japan’s ability to wage war lies within the capability of this command.” While city after city burned, B-29s aerially mined Japanese harbors and shipping lanes; the 12,000 sea mines they dropped severely degraded what feeble resupply capabilities remained after the strangling American submarine blockade. The Japanese responded with desperate but increasingly ineffectual defenses, including ramming the bombers. All told, some 400 B-29s were lost—a tiny 1.38 percent of the fleet.

LeMay’s incendiary campaign claimed some 330,000 Japanese lives. About 8.5 million were left homeless. Nearly half of the 67 firebombed cities were destroyed. The operation won LeMay the nickname “Demon” from the Japanese, who after raids tortured and executed not only downed B-29 crewmembers but Allied POWs. LeMay knew all this. He was aware of how brutal his actions seemed. But war, to him, was a question of ratios: you had to outkill the enemy. He rarely if ever revisited fundamental beliefs. And in the Pacific theater—where from the outset the Japanese slaughtered millions of civilians, and where their defensive strategy hinged on the delusion that the Americans, wearied by their own rising death toll, would ultimately settle for a negotiated peace—he had very little impetus to do so. “To worry about the morality of what we were doing—Nuts,” he later wrote.

Hap Arnold agreed wholeheartedly. Despite haphazard intelligence about the Japanese economy, Arnold assured a queasy Stimson that Japan’s industry was widely dispersed among the urban centers and that “they were trying to keep [civilian casualties] down as much as possible.” Precision daylight bombing, with its corollary of avoiding civilian targets, became another casualty of the Pacific war of attrition. Nighttime area bombing was now American gospel, and LeMay was its triumphalist public face. Joining the swelling media celebrations, Time magazine, in an August 1945 cover story, dubbed him “Very Long Range Man.” The self-made man, despite never attending West Point like his fellow commanders, had rocketed to the top of his profession—which happened to be war. Whether firebombing alone would have ended Japanese resistance is open to debate, but LeMay believed it could have.

As Arnold had claimed, Japanese war industries, like those in Great Britain, were dispersed throughout the cities, but unlike in Britain they were more at urban margins than in the centers. The centers, of course, were where LeMay’s bombers concentrated, and civilian lives and morale were inevitably among their primary targets. “Bomb and burn ‘em till they quit,” LeMay once explained. By August 1945, his B-29s were dropping leaflets that listed 11 Japanese cities, declared 4 would soon be destroyed by American bombs aimed at military installations, and added, “Unfortunately, bombs have no eyes…. You can restore peace by demanding new and good leaders who will end the war.” LeMay was an ideal field commander, Hap Arnold recognized, for a war of attrition spiked with terror. Still, LeMay had little to do with the ultimate terror of the atomic bomb, first loosed on Hiroshima on August 6, then on Nagasaki on August 9. Less than a week later Japan surrendered, and as the cold war loomed, it appeared the still-youthful General LeMay had a bright future ahead of him.

As LeMay continued his rise to the top after the war, however, it became apparent that the shrewd tactician and relentless fighter was no strategic thinker. He had no affinity or tolerance for gray areas, and his postwar career demonstrated how his flaws grew from his strengths.

His 1948 airlift to break the Soviets’ blockade of Berlin didn’t become truly workable until Maj. Gen. William H. Tunner took over; as Tunner himself observed, a combat command and an airlift operation demanded two very different skill sets. When LeMay was chosen to build the postwar Strategic Air Command out of desultory shards, he did so with his trademark organizational flair. But he never seemed to grasp that the nuclear weapons he built it to deliver were not just bigger explosives; his advocacy of using them (during the Cuban missile crisis, for example) brought him into ferocious conflicts with his civilian bosses and other military men. As chief of staff during the first half of the 1960s he starved the air force of tactical and support aircraft, which cost American blood in Vietnam; his infamous pronouncement about bombing North Vietnam back to the Stone Age was worthy of his caricature in the 1964 film Dr. Strangelove. For many, when he agreed to be George Wallace’s running mate during the 1968 presidential election, he besmirched his record even further.

Yet LeMay seemed to understand how a different perspective could bring a different view, uncharacteristically observing in later years, “I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal.” During World War II, his chief statistics officer had been Robert McNamara, whose analysis had directed LeMay’s crews and bombs to efficiently destroy targets. Later, as secretary of defense under John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, McNamara would become one of LeMay’s chief antagonists over hot-button issues: the Cuban missile crisis, the Vietnam War, and the B-70 bomber. As he looked back on his three years of service with the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II, McNamara called LeMay “the ablest commander of any I met.” But when he looked back on LeMay’s retrospective observation about the morality, even the possible criminality, of his own tactics, McNamara’s assessment was stark: “I think he’s right.”

Originally published in the January 2009 issue of World War II. To subscribe, click here.