The National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., realizes a dream first proposed by Civil War veterans.

One of the most affecting artifacts in the Smithsonian’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture is also its most delicate: a thin lace-and-linen shawl. Draped on a slight mannequin form and yellowed from the passage of time, the shawl conjures up the famous woman who wore it: Harriet Tubman. Looking at it, one can picture not just the two-dimensional face that has appeared in children’s history books or that will eventually grace the $20 bill, but instead the flesh-and-blood woman who risked her life numerous times to guide enslaved people to freedom, who was employed by the U.S. government as an armed scout and spy, and who may have gathered this garment around her frail shoulders as she entered the final years of her remarkably long life.

That is the value of museums and artifacts: They make the imagined concrete, and they bring history into the present. That may be the case with this museum more than any others in the Smithsonian Institution. With “culture” added to “history” in the title, the Smithsonian is acknowledging that, the past is not even past, to quote William Faulkner, when it comes to the quest of African Americans for equality in all aspects of life—the workplace, the battlefield, the political arena and the street.

“This landmark comes at a significant time in our history, for the Smithsonian and for our country,” said David J. Skorton, secretary of the Smithsonian, at a special event related to the September opening of the museum. “It occurs as racial and cultural differences dominate our national discourse.”

With its striking crown shape, the 400,000-square-foot museum sits in a prominent place on the Washington Monument grounds in Washington, D.C. It contains more than 3,000 artifacts representing the broad sweep of the African-American experience, from the slave ships crossing from Africa through the Civil Rights movement of the 20th century and into the current realms of politics, sports, activism and the arts. Perhaps not surprisingly, however, the emotional core of the museum lies in its 19th-century collections, in a series of galleries covering slavery, war and emancipation.

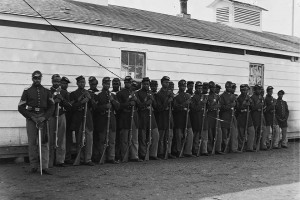

Civil War veterans spawned the idea for a national African-American history museum a century ago. In 1915, after they had been excluded from a 50th anniversary event, veterans of the U.S. Colored Troops formed a Committee of Colored Citizens of the Grand Army of the Republic as an effort to recognize their military service. This impulse later evolved into a movement to create a museum depicting the contributions of African Americans across all fields, an effort that waxed and waned throughout the 20th century until Congress finally approved the museum’s creation in 2003.

Once Congressional funding was secured, the Smithsonian launched an international design competition to choose the museum’s architects. As with the National Museum of the American Indian before it, there was widespread understanding that this museum would eschew the staid neoclassical style of older Smithsonian buildings such as the Museum of Natural History, in favor of a design that better told its unique story. Ultimately, the design was awarded to a partnership among four architecture firms, the Freelon Group, Adjaye Associates, Davis Brody Bond, and the SmithGroupJJR. Led by design architect David Adjaye, a Ghanaian British national, the design centers on two primary elements: the “corona” or crown, the three-tiered shape that is clad in 3,600 bronze-colored cast-aluminum panels, and the “porch,” a nod to African-American (and Southern) culture that is expressed in a broad welcome plaza. The corona is rooted in African history, mimicking the Yoruban Caryatid, a traditional wooden totem with a similar crown on top (an example can be found in one of the galleries). The exterior is punctuated by a series of windows, which the architects call “lenses,” that frame iconic scenes along the National Mall and remind visitors of African American history’s rightful place in that tableau.

Inside, the museum contains 12 inaugural exhibitions organized around three themes: history, community and culture. One descends into the subterranean history gallery first, and it’s no coincidence that an early, and eerie, experience for visitors is to step into the recreated bowels of a slave ship. Near the ironic words of the Declaration of Independence stating “all men are created equal,” we see shackles that are small enough to fit a child’s ankles. We read a passage revealing that, in 1857, “a hundred thousand new-born babes are annually added to the victims of slavery.” We see an early-1800s slave cabin, painstakingly moved and restored from Edisto Island, S.C. We see a bill of sale for a girl named Polly, aged 16, sold for $600. We also see the freedom paper carried in a tin box by Joseph Trammel in 1852, when a “man of dark complexion,” as the paper states, required someone else’s signature to secure his basic human rights.

Rather than engage in the war of words about what Northern and Southern soldiers were really fighting for, the museum focuses on how African Americans fought for their own freedom, whether in uniform or not. The museum quotes “a colored man” in New Orleans, speaking in 1863: “Our union friends…say we are fighting for the union…very well let the white fight for what the[y] want and we Negroes fight for what we want….Liberty must take the day and nothing Shorter.”

Wartime artifacts—including muskets and uniforms—are included alongside famous images of Sergeant Samuel Smith, an African-American Union soldier, and his family, as well as Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Troops, lined up at Fort Lincoln in Washington, in November 1865. The museum finds the latter image important enough to include it twice, once in this main history gallery and once also in the upstairs section devoted to African-American military service.

More than the artifacts, what truly distinguishes this museum’s slavery and Civil War section from others devoted to the period is that the story doesn’t end at Appomattox Court House or with the passage of the 14th amendment. The story of hope and the quest for empowerment continues in the upper galleries, which include a segregation-era railway car, a lunch counter evoking anti-segregation sit-ins, a vintage Tuskegee Airmen’s plane, Michael Jackson’s fedora, Gabby Douglas’ Olympic credentials and much more. The stories continue and they are connected, and that’s the point.

Any major new building in the nation’s capital would be subject to criticism, but an institution this complex and this weighted with expectation was bound to receive its fair share of critique. In his review, The Washington Post architecture and culture critic Philip Kennicott expressed concern that the museum is difficult to navigate, adding that “the history it tells often feels disconnected and episodic.” In The Guardian, Steven W. Thrasher praised many elements of the museum but called it “a monument to respectability politics” that might allow people to gloss over the difficult truths of African-American lives. “[A] museum like this is also bolstering a national American identity,” Thrasher wrote, “so it has high ambitions which deserve to be scrutinized.”

The criticisms are probably warranted. This is a museum with sharp corners, literally; there is no easy, circular flow from place to place, which could also be construed as a way to keep visitors alert and engaged rather than mollified. The stories being told are so rich and resonant, the artifacts so numerous and the interactive displays so dazzling, that one can easily feel overwhelmed. And yet it is also easy to feel a sense of satisfaction that the vision of those U.S. Colored Troops a century ago, and of so many advocates since, has been fulfilled.

Will some allow that satisfaction to blind them to hard realities? Probably. But museum officials and designers clearly hope that this museum will help to start conversations rather than stifle them.

Just before her death in 1913, when she was 90 or 91 (no one knows for sure), Harriet Tubman quoted scripture to those gathered around her, saying, “I go to prepare a place for you.” With the opening of this moving museum, a special place has been prepared for Tubman and for so many others who have gone before and given so much. It’s a place for all of us.

Kim A. O’Connell, based in Arlington, Va., has written about the Civil War for The New York Times, National Parks, National Geographic News and other publications.