“If Abrams strongly recommends it, we will do it.”

President Richard Nixon to adviser Henry Kissinger

—White House Tapes, Dec. 9, 1970

Presidential confidence in the MACV leader had deteriorated and would continue to erode

That Oval Office conversation was the high point of the commander in chief’s relationship with four-star Gen. Creighton Abrams Jr., head of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, which oversaw all American combat forces inside South Vietnam. By the spring of 1971 presidential confidence in the MACV leader had deteriorated and would continue to erode throughout Abrams’ tenure as the top U.S. military man in Vietnam during the final years of the war.

Gruff and sometimes disheveled, Abrams was the antithesis of his predecessor, the upbeat, immaculately groomed Gen. William Westmoreland. “Abe” inspired the troops with his competence, plain talk and combat record. During World War II, he received two Distinguished Service Crosses, America’s second highest award for valor, and was cited by Gen. George Patton as the best tank commander in the U.S. Army. The troops in Vietnam considered him a soldier’s soldier.

After assuming command of MACV in June 1968, Abrams re-energized the American advisory effort that assisted South Vietnamese troops and integrated the Army of the Republic of Vietnam into U.S. operations. He also shied away from Westmoreland’s large search-and-destroy missions, instead emphasizing securing and holding populated areas. The MACV commander had to balance these programs with the mid-1969 introduction of President Richard Nixon’s “Vietnamization” policy, which called for gradual withdrawal of U.S. forces while modernizing the ARVN. There was no question that the United States was leaving Vietnam; the final “when” was unspecified.

After 1969 Abrams was relegated to fighting a prolonged rear-guard action. Yet he was always looking for a chance to take the offensive. One of those opportunities came in March 1970 with the overthrow of Prince Norodom Sihanouk in Cambodia, where Communist sanctuaries had been established in the supposedly neutral country. The coup installed a more U.S.-friendly government in Phnom Penh, which allowed American and South Vietnamese forces to strike the enemy havens that been a thorn in the side of U.S. commanders.

At the end of April 1970, Abrams launched a combined ARVN-U.S. attack on the sanctuaries, disrupting supply and staging bases for the North Vietnamese Army. Although the NVA withdrew without fighting a major battle, the MACV commander received high marks from the president and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. However, the outrage across America over perceived expansion of the war caused Nixon to terminate the mission earlier than planned, limiting its effectiveness.

Notwithstanding public aversion to another cross-border assault, the president gave approval on Dec. 9, 1970, for an incursion into Laos. Abrams had lobbied hard for what would be called Lam Son 719. The operation’s name was derived from revered 15th century emperor Le Loi’s home village of Lam Son in northern Vietnam. The 719 number was used to indicate the operation would be conducted in 1971 along Highway 9, the primary axis of advance.

Because Congress had prohibited the deployment of American ground troops outside of South Vietnam, no advisers participated in the campaign. The prohibition did not apply to aviation. U.S. Army helicopters, Air Force B-52 bombers, and Navy and Air Force fighter-bombers provided strong support, but that assistance had to be coordinated by South Vietnamese officers. Previously, American advisers had handled those tasks.

Lt. Gen. Hoang Xuan Lam was designated the overall commander of Lam Son 719. The general, a strong ally of President Nguyen Van Thieu, was in charge of South Vietnam’s five northern provinces, the military region designated I Corps. But Lam was primarily an administrator, not a tactical corps commander. He and his staff were unprepared for the challenges of directing multiple divisions and orchestrating a combined arms operations. The Laos operation would be conventional warfare, not the smaller insurgent engagements with Viet Cong guerrillas that South Vietnam’s leaders were used to overseeing.

South Vietnam’s best units—the Airborne Division, Marine Division and 1st Infantry Division—were part of Gen. Lam’s force. The incursion force assembled near the Khe Sanh combat base in South Vietnam, and its lead elements entered Laos on Feb. 8, 1971. Their objective was Tchepone, a logistical hub along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, about 25 miles from the Vietnamese border.

Speed and aggressiveness were imperatives for success. However, the pace was slowed by command and control problems. Lam’s forward headquarters was in Dong Ha, 30 miles from most of his subordinate units’ command posts at Khe Sanh—a distance that meant most communication was conducted by telephone and radio, instead of face-to-face. Additionally, poor coordination and lack of clarity in orders prompted confusion and hesitation. The Airborne Division, which had never operated in a formation larger than a brigade task force, experienced similar issues.

The country’s president could not resist assuming the role of a tactical leader. At an I Corps meeting on Feb. 19, Thieu told his commanders “to conduct search operations in the vicinity of their present positions,” guidance that created an overabundance of caution. As a result, many ARVN units stayed on their firebases and made little progress. No amount of pressure from the U.S. advisory chain could overcome the growing inertia.

South Vietnamese timidity took the pressure off the NVA, whose forces immediately went on the offensive. North Vietnamese units surrounded ARVN firebases, pounded them with artillery and mortar fire and ringed them with anti-aircraft weapons that restricted U.S. helicopter and close-air support. NVA armored vehicles supported the infantry assaults on the firebases. One by one, stationary ARVN units were overwhelmed. Anti-aircraft fire made aerial resupply and troop lifts hazardous. More than 100 U.S. helicopters were lost trying to break NVA strangleholds.

Even as the NVA gained the upper hand, Abrams continued to send positive reports to Washington. He believed Lam and others would get their act together and become more aggressive. It was a major miscalculation, which the president and national security adviser Henry Kissinger would not forget.

Abrams’ upbeat assessments were in sharp contrast to press reports telling of a disaster in the making. The White House bombarded Adm. Thomas Moorer, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, with questions and demanded to be told what was really happening in Laos. As a result, Moorer’s confidence in Abrams also was shaken.

Conditions on the ground deteriorated further on March 9 when the South Vietnamese president unilaterally ordered a withdrawal of all ARVN forces, which senior U.S. leaders had hoped would remain in Laos through April. Thieu had lost his nerve when confronted with all the casualties and disorganization. Adding insult to injury, on April 7, Nixon had to go on national TV touting Lam Son 719 as a positive affirmation of Vietnamization. His remarks were not in sync with what the American public had read and seen over the past month.

The president came very close to relieving Abrams, blaming him for much of the debacle. When the dust settled, he decided not to take such drastic action. Nixon, an astute politician, may have wanted to avoid a repeat of the public furor that erupted during the Korean War when President Harry Truman relieved another iconic general, Douglas MacArthur.

An extensive post-mortem followed. The Joint Chiefs asked Abrams why he had urged the Laos attack when South Vietnamese senior commanders were unable to “hack it.” Chairman Moorer concluded that the capabilities of the ARVN had been grossly overestimated and the incursion should not have been undertaken. Moorer was determined to learn about future crises much sooner and keep the White House better informed.

Hanoi drew lessons from Lam Son 719 too. All North Vietnamese leaders were committed to “liberating” the south, but how to do it had been the subject of extensive discussion. One faction led by Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap, who received credit for the massive 1968 Tet Offensive assaults across South Vietnam, argued that more time should be allowed for all U.S. forces to withdraw before initiating another general offensive. However, Le Duan, secretary-general of the Vietnamese Communist Party and a leading advocate of more aggressive action, was certain the NVA would defeat the ARVN in a toe-to-toe fight even if the South Vietnamese were supported by U.S. air power. The recent actions in Laos supported his conclusion.

When the pace of American withdrawal accelerated in the summer and fall of 1971, Le Duan convinced his more cautious colleagues of the need for an all-out offensive in 1972 that would topple the Thieu government with a stunning military victory, drain the remaining U.S. resolve and thwart Nixon’s re-election bid. The Communists’ planned invasion, the largest of the war, was called Nguyen Hue in honor of an 18th century emperor who unified the country.

The assault involved 120,000 soldiers, organized into 14 divisions and 26 independent regiments. Infantry forces were augmented with 500 tanks, heavy artillery and mobile air-defense batteries. There were large quantities of Soviet weapons not previously seen south of the Demilitarized Zone separating North and South Vietnam. Those weapons included M-46 130 mm field guns, SA-7 heat-seeking anti-aircraft missiles, AT-3 anti-tank missiles and T-54 tanks with a 100 mm main gun.

Rather than mass the entire force for a single stroke, Communist planners opted for three separate attacks: in the north, aiming at the ancient imperial capital of Hue, the cultural heart of Vietnam; in the Central Highlands, hitting Kontum, where a quick victory might lead to severing the country; in the south, using Route 13 from Cambodia as the axis for an advance to take the South Vietnamese capital at Saigon.

Operation Nguyen Hue commenced on Thursday, March 30, 1972, when NVA forces stormed into northern I Corps. Since the day marked the beginning of Easter celebrations, the American press called the attacks the Easter Offensive. The recently activated 3rd ARVN Division was no match for the veteran NVA troops who led the assault. However, two brigades of Vietnamese marines held the line, enabling friendly forces to conduct an orderly withdrawal to a new defensive line near Dong Ha, 10 miles from the DMZ. On April 5 three NVA divisions left their Cambodian assembly areas around Route 13, overran the town of Loc Ninh and besieged An Loc, a provincial seat 60 miles from Saigon. A week later ARVN forces around Kontum were locked in a deadly struggle to hold South Vietnam’s midsection.

The drawdown of U.S. forces had left only about 50,000 American troops in-country, compared with the half-million Americans in Vietnam in 1968. Just two U.S. combat brigades remained. They secured air bases at Da Nang in the north and Bien Hoa near Saigon. Unless attacked, those units would not enter the fight. Thus, aviators and advisers were the principal American combatants during the Easter Offensive.

The North Vietnamese assumed domestic and election-year constraints would discourage a strong U.S. response. But Nixon reacted forcefully, sending in additional aircraft carriers, Air Force fighters and B-52s to counter the NVA. The number of warplanes in the theater soon doubled. American advisers with South Vietnamese units provided timely intelligence on potential targets for those aircraft and made airstrike adjustments. Within a month Nixon ordered the mining of North Vietnam’s main seaports, cutting the country’s primary external supply lines. In a national TV address the president said he had resumed bombing in the north.

To the surprise of the revolutionaries in Hanoi, the bulk of the American public supported Nixon’s actions, and there were only perfunctory protests from the Soviet Union and China. The North Vietnamese sense of unease increased when a scheduled U.S.-Soviet summit, set for mid-May in Moscow, proceeded as planned.

The aerial reinforcements, bombing and mining did not immediately alter the course of the confrontation. The NVA had the initiative and in several locations enjoyed significant numerical superiority, but the South Vietnamese defenders were holding on. Some in Washington, who had earlier received positive reports about post-Lam Son 719 training and refitting, wondered why certain ARVN units were still performing poorly after the expenditure of so many U.S. resources, but they didn’t take into consideration the fact that those units were vastly outnumbered. As before, Abrams bore the brunt of this emerging criticism from Kissinger and others.

Poor senior leadership, especially in I Corps, continued to plague the ARVN. Staff deficiencies that emerged in Laos had not been rectified, nor had inept commanders been reassigned or retired. Political loyalties, family connections and business affiliations trumped military professionalism.

Abrams sent daily appraisals to the commander in chief of the Pacific Command, Adm. John McCain (father of the prisoner of war and future senator), and Joint Chiefs Chairman Moorer. Abrams, along with Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker, also provided updates to Maj. Gen. Alexander Haig, Kissinger’s military assistant. Initial cables were relatively positive, even when the South Vietnamese were struggling. The MACV commander was reluctant to predict the “sky was falling” when the situation was not fully developed. The higher-ups, citing misleading message traffic from the previous year, immediately questioned Abrams’ dispatches and believed the situation in Vietnam was far more critical than was being portrayed.

Abrams’ positive assessments abruptly changed on May 1, when South Vietnamese soldiers in I Corps abandoned the city of Quang Tri and fled south in panic. The MACV commander explained that although Vietnamese marines held the line a few miles north of Hue, the ARVN was approaching a breaking point. With disaster looming, Thieu relieved Lam and several other incompetent commanders. South Vietnam’s best soldier, Lt. Gen. Ngo Quang Truong, was sent to stabilize the situation in I Corps. His presence made an immediate difference. Even so, Nixon’s dissatisfaction with Abrams continued to grow. Once more there was talk of relieving the general of his command.

The Easter Offensive had just started when Moorer picked Air Force Gen. John W. Vogt Jr., a White House favorite, to be commander of the 7th Air Force and deputy commander of MACV, making him the senior airman in Vietnam. The fighter pilot had previously impressed Kissinger with his Ivy League credentials, including an undergraduate degree from Yale University, a graduate degree from Columbia University and a fellowship at the Harvard School of International Affairs. Vogt was regarded as brilliant staff officer who knew how to navigate in high-level political circles. He had been involved in planning the Rolling Thunder bombing campaign against North Vietnam from 1965 to 1968.

The new MACV deputy commander was rushed to Vietnam and became the Joint Chiefs chairman’s main source of information and advice from Saigon. Vogt used his Air Force communication channel to bypass both of his superiors, Gen. Abrams at MACV and Adm. McCain of the Pacific Command. He sent his assessments directly to Moorer, who briefed Kissinger. Vogt vilified South Vietnam’s generals and complained that lower-ranking enlisted men lacked the will to fight—an assessment from a man who was never eye-to-eye with North Vietnamese infantrymen. His statements diverged from reports rendered by many U.S. infantry advisers who said the individual soldiers did all that was asked of them and more.

The Washington mole also took the White House’s side in huge disagreements over air power allocations. Nixon and Kissinger wanted to put most of the B-52s on missions over North Vietnam. They believed the big bombers were a display of U.S. determination that would persuade Hanoi’s Communist allies, China and the Soviet Union, to limit their logistical support and encourage North Vietnam’s Politburo to end the fighting through a negotiated settlement.

Bucking that view, Abrams wanted large numbers of B-52s and other combat aircraft in South Vietnam to blunt the Communist ground offensive there. The bombers were instrumental in stopping the NVA outside Hue, Kontum and An Loc. Abrams fought hard for an ever-increasing share of those sorties, and Vogt couldn’t sway the MACV commander to Washington’s point of view.

Kissinger, frustrated with what he saw as Abrams’ intransigence and insensitivity to the president’s strategy, sent Haig to Saigon to explain the administration’s position. Abrams, however, reminded Haig that superpower signals to China and the Soviets would mean very little if South Vietnam fell to the Communist onslaught. Haig, an infantryman who had served as a battalion and brigade commander in Vietnam, got the message and took it back to his boss.

The push-pull between the president and his Vietnam commander was somewhat attenuated in mid-June 1972 by a significant reduction in NVA activity. Intelligence reports indicated that Operation Nguyen Hue had run its course. Continuous airstrikes had devastated the enemy. Thousands of NVA soldiers were killed. The battlefields were littered with enemy war debris, particularly T-54 tanks. In North Vietnam, mined seaports coupled with the destruction of bridges and rail lines restricted movement of critical NVA supplies. Abrams’ tour of duty ended in late June as ARVN troops regained their footing and launched a multidivision counterattack. Fighting continued, but the momentum had shifted in favor of South Vietnam and the U.S.

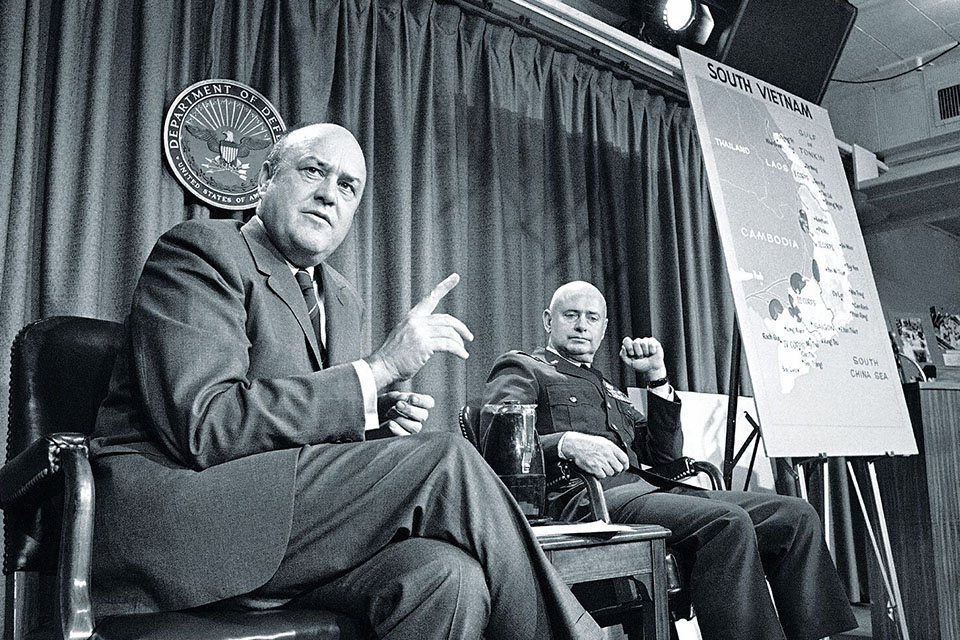

Defense Secretary Melvin Laird, always an Abrams supporter, urged the president to nominate the MACV commander to become Army chief of staff, replacing Westmoreland, who had been named to that position after leaving Vietnam and was retiring. More than other senior administration officials, Laird appreciated that Abrams had been given the extremely difficult job of conducting a strategic withdrawal while fighting a determined enemy. Nixon balked at the recommendation, citing what he perceived as Abrams’ lack of candor in reporting ARVN performance. But Laird called in a marker. When he had agreed to head the Defense Department, Laird insisted on complete authority to fill key positions. Honoring that commitment, Nixon forwarded Abrams’ nomination to the Senate.

The general was subjected to lengthy congressional investigations upon his return to Washington, and a hostile Congress dragged out the confirmation process until October 1972. Ironically, Abrams’ first task as Army chief was to return to Saigon and get Thieu’s concurrence with a secret peace agreement crafted by Kissinger and North Vietnamese negotiator Le Duc Tho. Thieu objected to a “cease-fire in place” that allowed NVA forces to remain in South Vietnam after the fighting ended. He was ultimately bullied into accepting the objectionable provision.

After the implementation of the January 1973 cease-fire, Abrams focused on repairing the damage inflicted on the U.S. Army by the lengthy, unpopular war. His premature death on Sept. 4, 1974, from a cancer-related operation, cut short those efforts. Six years later the Army honored him by naming its new M1 main battle tank the “Abrams.”

During the Easter Offensive U.S. aviators, advisers and their ARVN counterparts had defeated the NVA using the assets Abrams obtained when he challenged the president of the United States over aircraft allocations. Those strikes saved the day, and the men on the ground would forever be grateful to “Abe” for making it happen.

—John D. Howard served in the U.S. Army for 28 years, retiring as a brigadier general. His research for this article included the White House tapes, memoirs of Nixon and Kissinger, MACV Command History, Lewis Sorley’s Abrams books, William Hammonds’ Reporting Vietnam and Lien-Hang T. Nguyen’s Hanoi’s War. During the 1972 Easter Offensive, Howard was a battalion adviser with the Vietnamese Airborne Division.

Featured in Vietnam magazine’s December 2017 issue.