Heinkel produced one of the most innovative night fighters of World War II, but Nazi bureaucrats repeatedly shot it down

There were many night fighters in World War II, but only two were designed from the ground up to play in the dark: the Northrop P-61 Black Widow and the radar-laden Heinkel He-219. The rest were modifications of fighters and light bombers originally intended solely for daylight battle, and the results ranged from superb—particularly the Messerschmitt Me-110G and several versions of the de Havilland Mosquito—to nearly useless.

The He-219 was neither superb nor useless, but, as the fifth grader’s report card reads, it did not work up to its potential. It was a classic underachiever.

The hardest battles the He-219 fought were political. The airplane was repeatedly canceled by the German air ministry (Reichsluftfahrtministerium, or RLM) and then surreptitiously ordered back into production by its enthusiasts in the Luftwaffe. The controversy over the Uhu—unofficially named after a large Eurasian horned owl—had ministers, manufacturers and military men all fighting like tomcats in a flour sack. By the time these fools were fired, transferred, dead or otherwise disposed of, fewer than 300 He-219s had been manufactured. Nobody knows the exact number—288 is a frequently published guess—since record-keeping was not a Nazi priority as the war wound down.

The He-219’s most intractable opponent was Erhard Milch, the field marshal in charge of German aircraft production. Besides intensely disliking the dislikable Ernst Heinkel, Milch wanted to rely upon night fighters based on existing designs—especially the Junkers Ju-188, an uprated version of the simple, versatile and proven Ju-88. Quantity trumped quality, Milch believed. Better to have hordes of good night fighters rather than a few great ones.

Designed in the 1940 and first flown in 1942, the Uhu entered combat in June 1943. The airplane was all done, literally out of gas and with too few trained crews to fly it, a year and a half later, well before the war in Europe ended in May 1945. The last He-219 victory was notched on March 7 of that year.

If thousands of He-219s had been built, would they have changed the war? At worst, they could have forced the RAF to join the Americans in day bombing, which might not have been bad thing. In a famous May 1945 interview with Lt. Gen. Carl Spaatz, Luftwaffe leader Hermann Göring admitted that U.S. Army Air Forces daylight raids were far more effective than the RAF’s night area bombing. “The precision bombing was decisive,” Göring said. “Destroyed cities could be evacuated, but destroyed industry was difficult to replace.”

Some say the Uhu could have been the best night fighter over Europe. Others, particularly Eric “Winkle” Brown, the legendary Royal Navy test pilot who flew several He-219s after the war, thought it was overrated. The Uhu, he wrote, “had perhaps the nastiest characteristic that any twin-engine aircraft can have—it was underpowered. This defect makes takeoff a critical maneuver in the event of an engine failing, and a landing with one engine out can be equally critical. There certainly can be no overshoot [go-around] with the He-219 in that condition.”

Still, the He-219 had several strengths. With three fuselage fuel tanks the size of dumpsters, it was able to loiter for four or five hours to wait for ground radar to find it targets, while other Luftwaffe night fighters typically had to go home after 90 minutes or so. Its cockpit was superbly laid out and roomy in an era when pilots typically worked amid unplanned jumbles of controls, switches and instruments. At one point, it was suggested that the He-219’s entire bolt-on, two-seat cockpit unit be grafted onto the Ju-188. The He-219’s ordnance was overpowering—a maximum of two cannons in the wing roots, four more in a belly tray under and behind the cockpit and yet another pair in an upward-angled Schräge Musik installation amidships.

(It has become aviation lore that Schräge Musik means “jazz music,” but that is a canard that has taken on a life of its own among amateur Luftwaffe historians. Translated literally, Schräge Musik means “slanted music,” which makes perfect sense, since the gun barrels are slanted, and we can accept the concept of gunfire being “music.” Native German speakers affirm that the term Schräge Musik was never applied to jazz.)

The guns were not only overpowering but overkill. One or two well-aimed rounds from a 30mm cannon would almost certainly be enough to bring down a bomber, and six simply sealed the deal. Many crews removed all but two of the heavy belly-tray and wing-root guns, and some sources say that not a single He-219 in I Gruppe of Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 (I/NJG.1)—the sole air group to be fully equipped with Uhus—carried a Schräge Musik mount.

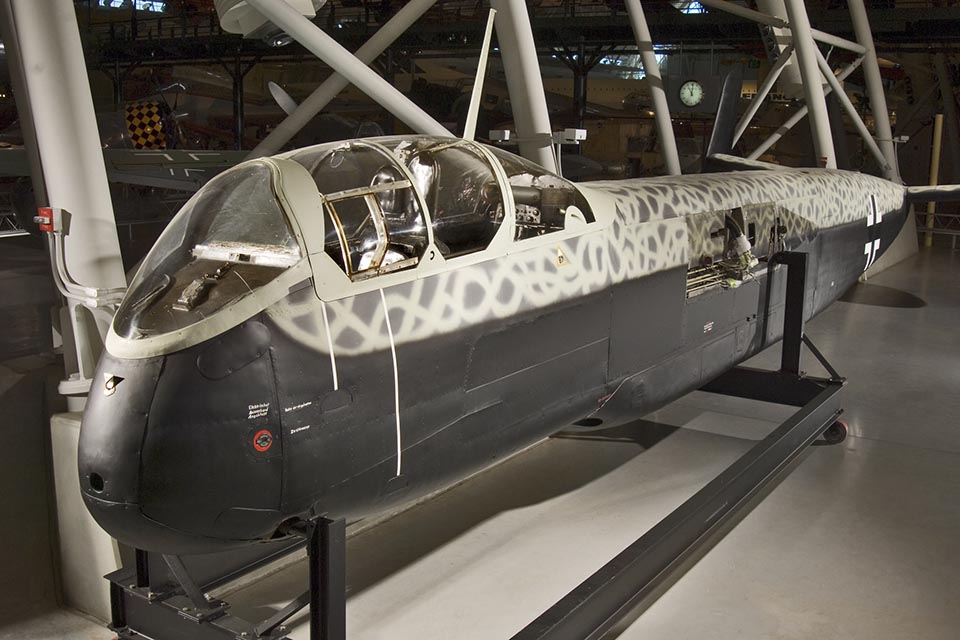

Many a metaphor has been expended to describe the appearance of the Uhu. Its long, skinny fuselage is flanked by lengthy engine nacelles atop stalky landing gear, and its most distinctive feature is a reptilian canopy that uncannily resembles—allow me another overripe metaphor—the carapace of the slavering, thorax-slashing monster in the film Alien.

German designers were good at reducing cooling drag for engines that required radiators, and rather than slinging the big brass heat exchangers under the wings or in a bluff chin configuration, they chose annular radiators—interconnected coolers arrayed in a circle around the front of the engine. This had two advantages: efficient cooling, and since a liquid-cooled engine’s Achilles’ heel is its vulnerable plumbing, the ability to concentrate all the engine’s pipes, hoses and tubing within a compact, easily armored area—no long runs to wing- or belly-mounted radiators.

Those round nacelles provide ample reason to assume the He-219 was powered by radial engines, but in fact they were Daimler-Benz DB 603 inverted V12s. Supposedly supertuned to put out 3,000 horsepower, the 603 was originally mounted in the six-wheel, Ferdinand Porsche–designed Mercedes-Benz T80 land speed record car. At 44.5 liters—65 percent larger than a Rolls-Royce Merlin—it was by far the largest V12 the Luftwaffe ever flew.

The He-219 was designed to use the 1,875-hp DB 603G, but that never made it into production, underscoring the dangers of combining an unproven engine with a brand-new airframe. Because the He-219 had to fly with less powerful versions of the 603, its rate of climb and speed never met predicted numbers. The fact that it was lumbered with a ton of cannons and every piece of air-intercept electronics the Germans could cram into it didn’t help. The empty weight of a typical He-219 was greater than the weight of a fully fueled, ammoed and crewed Mosquito.

Nor did the nose-mounted array of high-drag external radar antennas, commonly called stag’s antlers, help. They slowed the airplane noticeably, and not until early 1945 did the Germans come up with a cavity magnetron dished radar that could be mounted inside a radome like U.S. units. By then, it was irrelevant.

Robert Lusser had originally worked as a designer for Heinkel but moved to Bayerische Flugzeugwerke in 1933, where he and Willi Messerschmitt laid out the Bf-109 fighter. In 1938 Lusser returned to Heinkel and designed the He-280, the world’s first jet fighter, though it lost out in production to the Me-262. Lusser also began laying out the airplane that would, through several twists and turns, ultimately cost him his job: the He-219. (When the RLM twice rejected Lusser’s initial He-219 proposals, Ernst Heinkel fired him. Lusser went on to Fieseler, where he refined the design of the V-1 buzz bomb, and in the early 1960s made a small fortune by designing the world’s first modern quick-release ski binding.)

Heinkel had already built a high-speed reconnaissance/bomber prototype, the He-119. In a sense, the 119 was the predecessor of the 219, despite the fact that its DB 606 power plant—actually two coupled DB 601 inverted V-12s—was buried behind the cockpit and drove contrarotating props on its nose. The entire fuselage was cleanly cigar-shaped, and the pressurized cockpit was the fully glazed tip of the cigar, with the prop shaft running at biceps height between the two pilots.

Lusser took a new cut at the concept and came up with a tricycle-gear twin that also had a pressurized cockpit and ejection seats, plus remotely controlled defensive armament of the sort that would later appear on the Boeing B-29. Many published sources say the He-219’s nosewheel was steerable, which would have been another notable innovation. But the Uhu’s nosegear was in fact free-castering, swiveling only in response to differential power or braking.

The ejection seat, however, was another matter. It was a major advance that predated anything of the sort in Allied aircraft, even though the British Martin-Baker company would go on after the war to set the standard for fast-jet ejection seats. The Germans and the Swedes had been working in parallel on ejection-seat design. Both Saab and Dornier were designing fighters with pusher props—the J21 and the Do-335—that would Cuisinart a pilot making a conventional bailout, and Heinkel had the He-280 jet in the works. The need for assisted bailout was becoming increasingly apparent; in the case of the He-219, the crew sat well ahead of the propellers, and since the reliability of Heinkel’s Katapultsitzen was questionable, those big props would remain a fearsome obstacle throughout the airplane’s brief career.

Junkers had pioneered ejection seats with a late-1930s patent for a “bungee-assisted escape device” that fortunately never went beyond the patent application paperwork. Saab accomplished the first-ever in-flight ejection, though with a dummy in a cartridge-fired seat, in January 1942. Less than a week later, a German test pilot did it for real, punching out of an He-280 prototype after encountering icing in a snowstorm. In April 1944, an He-219 pilot and radar operator ejected during an attack by a Mosquito—the first-ever combat ejection. Ernst Heinkel awarded each of them a thousand Reichsmarks (equivalent to roughly $1,300 today) for their troubles. Another He-219 pilot ejected three times, his back-seater twice—unfortunately too late for the Heinkel bonus.

Heinkel’s ejection seat was operated not by an explosive charge, like Saab’s, but by compressed air stored in an array of grapefruit-size spherical tanks for each seat. The system was vulnerable to leakage and, of course, battle damage to the pneumatics. About half the crew departures from He-219s were conventional jumps due to inoperable ejection seats.

The He-219’s entry into combat was the stuff of legend. Only one Luftwaffe night-fighter group, I/NJG.1, had been apportioned nearly all of the existing He-219s, many of them still production prototypes. On the night of June 11-12, 1943, the outfit attacked a huge stream of RAF bombers headed toward Düsseldorf. In an hour and a quarter—some sources say 30 minutes—a single Uhu crew shot down five of the big bombers and headed for home only because they had expended all their ammunition. (Karma’s a bitch: Pilot Major Werner Streib, I/NJG.1’s commander, crashed hard on landing when his flaps blew back up, and though he and his radioman survived with minor injuries, the Uhu became the sixth victim of that engagement.)

Legend indeed: One common He-219 myth holds that during the following 10 days, Uhus shot down 20 more British bombers, including six of the formerly untouchable Mosquitos. There is no evidence that anything of the sort took place. Not a single Mosquito was beaten by an He-219 during all of 1943, and the Uhu didn’t down its first Mossie until May 1944. By the end of the war, more He-219s had been shot down by Mosquitos than the reverse.

The RLM had rejected Robert Lusser’s original He-219 concept because of its complexity—pressurization, ejection seats, remote-control gun barbettes, tricycle landing gear, manufacturing challenges, untried engines. Heinkel set out to simplify and rationalize the Uhu, and the design was finally put into limited production. But Heinkel never stopped tinkering with the airplane. Rather than concentrating on one or two variants and building them in meaningful numbers, the company kept trying a variety of engines, crew configurations and armament setups. Though end-of-war confusion makes it difficult to establish a firm number, there may have been as many as 20 variants of the He-219 with 29 different gun setups.

Air forces hate single-mission aircraft like the He-219. They want airplanes that can drop bombs, strafe, dogfight, do reconnaissance, carry torpedoes and fly close air support. The He-219 could do nothing but fly at night to shoot down large, slow bombers. During the day, it was itself large and slow. This made it difficult to train new Uhu crews, since the basics of such training had to be done during daylight in a combat zone.

A fast-bomber version of the He-219 was proposed, as was a long-wing, high-altitude reconnaissance model. Heinkel planned to build a jet-powered He-219 and tested a BMW 003 turbojet in a pod under the belly.

And always the phantasm of a Mosquito-beater was pursued. Heinkel lightened the He-219, limited fuel, deleted guns and added power to achieve a book speed of 400 mph, but that airplane was never produced. In the real world, the best the He-219 could achieve was parity with some of the de Havillands. The supreme Mosquito Mark 30 night fighter, however, could bitch-slap the Heinkel at will. The RLM even briefly pursued a project called the Hütter Hu-211, which would have created a U-2-like He-219 using the Uhu’s main structure and engines with high-aspect-ratio wooden wings and a V tail built by sailplane specialist Hütter. It was to fly high and fast enough to evade Mosquitos, but the prototype was destroyed during an air raid.

Keeping complex He-219s operable became increasingly problematic as the war progressed. One Uhu pilot wrote: “It was rare that more than 10 machines took off on a night mission, usually less, and of those half either returned immediately after takeoff or were forced to land within the next half hour on account of malfunctions or problems. In the majority of cases, it was onboard electrics that failed.”

The airplanes were frequently parked outdoors and suffered condensation and water leaks. Those Uhus were flown every two or three days to air them out. Thanks to damp electrics, one He-219 pilot found himself in perfect firing position behind an RAF bomber, but when he pressed the trigger button, his landing lights came on. He admitted that it was hard to say who was more frightened—attacker or target.

When Germany surrendered in May 1945, few Uhus remained. The RAF ferried five of eight flyable He-219s from a night-fighter base in Denmark to England and sent the remaining three to Cherbourg, where they and a number of other Luftwaffe aircraft were loaded aboard a British escort carrier and shipped to Newark, N.J., then flown or trucked to Freeman and Wright fields, in Indiana and Ohio. At Freeman Field, one of the Uhus was reassembled and test-flown for 14.7 hours—the last time a Heinkel He-219 would ever fly.

One unusual piece of He-219 technology that intrigued the Army Air Forces testers and has thus survived is the “ribbon parachute” used to slow and stabilize the ejection seat after it was fired. Ribbon-and-ring chutes based on that German design have since been used to brake everything from top-fuel dragsters to space capsules.

Of the three Uhus that came to the U.S., one was scrapped at Chicago’s Orchard Place Airport (today called O’Hare). Another simply disappeared, doubtless scrapped elsewhere.

The Freeman flyer, however, still exists. It is today in the final stages of a complete static restoration at the National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center at Dulles Airport. European Aviation Curator Evelyn Crellin points out that it is actually something of a composite, having been reassembled at Freeman Field with engines and vertical stabilizers from the other two Uhus.

Crellin can’t give a firm date for the completion of the restoration, for the last major task that remains is rejoining the fuselage and the huge, one-piece wing. If it can be done inside the Udvar-Hazy museum building, where the wing and fuselage are currently on display along with the two restored DB 603 engines, it might happen as soon as this summer. If the components have to be reunited in the museum workshop, the job will take substantially longer.

Even then, there will be one task left: replication of the stag’s horn FuG 220 radar dipoles and mast, which disappeared long ago. Though Smithsonian restorers could easily mock them up from lengths of tubing and fabricated pieces based on old photographs, they insist on creating functional replicas of the original units, and all that is known about them is that they were made of steel, aluminum and wood. No records of their actual construction have yet been found, though one original antenna array exists in a museum in Europe, which the Smithsonian will borrow and reverse-engineer.

Another example of the workshop’s insistence on authenticity is that during restoration, removal of the Uhu’s wing-root fillets exposed the original wave-pattern camouflage paint still in perfect condition. It has been left untouched so that future researchers and historians will be able to examine it. When the fillets are screwed back in place, museum visitors will never see that there are areas of the airplane that remain unrestored.

The Smithsonian airplane is an apt example of the He-219’s unproductiveness. It was built in July 1944 and flew exactly 3½ hours before being ferried to France for shipment to the U.S. That time would account for a single production test flight plus the trip from the Heinkel factory to Denmark. In 10 months, it never flew a single combat mission.

Contributing editor Stephan Wilkinson recommends for further reading: Heinkel He 219: An Illustrated History of Germany’s Premier Nightfighter, by Roland Remp; and He 219 Uhu Volume I and Volume II, by Marek J. Murawski and Marek Rys.

This feature first appeared in the July 2016 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!