This article from the Spring 2010 issue of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History was a finalist for best short nonfiction in the 2011 Western Writers Association’s Spur Awards.

In the summer of 1858, Col. George Wright decided to fight terror with terror, pacifying the Northwest Indian warriors using sabers, treaties, lies—and the hangman’s noose

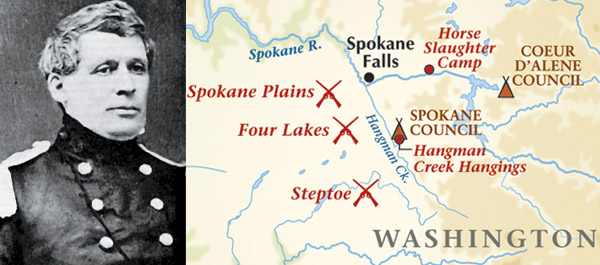

Western history is rife with epic clashes between well-armed Indian tribes and masses of United States soldiers: the Plains Indian Wars including Red Cloud’s War and the Great Sioux Wars, and the subjugation of the Kiowa, Comanche, Cheyenne, and Apache in the Southwest. But for all their open confrontations, federal commanders backed by military force also engaged in campaign after campaign of fear and terror—usually sparked by greed for Indian lands. Frequently, they were carried out with a blend of self-righteousness, prevarication, and unwarranted and unjust brutality. Col. George Wright’s foray against the tribes of the Upper Columbia Plateau in Washington in the summer and fall of 1858 was just such an ignominious campaign. Sparked by a need to show force and strengthen or create treaties, Wright’s advance devolved into a bloody and vindictive march featuring hangings, burned villages, lies and coercion, and the slaughter of nearly 700 Indian horses. The two-month-long sortie did permanently suppress the region’s native people, and settlers appreciated his effectiveness. Some 44 years later, the New York Times referred to it as “one of the most brilliant campaigns in the history of Indian warfare.” But Colonel Wright’s own words at the time were more to the point: “For the last eighty miles our route has been marked by slaughter and devastation.”

The seeds of Wright’s 1858 campaign had been planted a few years earlier. In 1853, the population of the Oregon Territory (encompassing not only present-day Oregon but also Washington State, Idaho, and those parts of Montana and Wyoming west of the Continental Divide) had increased enough to warrant carving the Washington Territory from it. Isaac Stevens, a 35-year-old West Point graduate and fervent supporter of Franklin Pierce in his winning 1852 presidential campaign, was appointed governor and superintendent of Indian affairs of the new territory.

Stevens also headed the surveying party looking for a path for a proposed transcontinental railway. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis placed him in command of surveying a northern route. In his three roles, Stevens aggressively set out to consolidate the tribes on reservations, to make way for the railroad and to allow whites to settle in greater numbers.

In May 1855, Stevens asked the chiefs of the inland tribes to meet him for a treaty in the Walla Walla Valley, in present-day southeast Washington State. Five thousand Indians showed up, primarily from Sahaptin-speaking tribes of the lower Snake River region: Nez Perce, Walla Walla, Palouse, Cayuse, and Yakama (spelled “Yakima” prior to 1994), among others. A small contingent of Salish-speaking Spokanes also attended, led by Chief Garry.

It took a few days for Stevens to cajole and coerce the chiefs to sign the treaties. He promised they wouldn’t have to move until the treaties were ratified (which, as it turned out, took four years). Yet immediately after the council, Stevens encouraged territorial newspapers to announce the opening of Indian lands to settlement. Numerous farmers, miners, and speculators showed up. Clashes between the settlers and the Indians were inevitable, and often bloody. Stevens’s former secretary later conceded that the governor had blundered by “cramming a treaty down their throats in a hurry.”

In early 1856, Col. George Wright brought more than 700 men of the 9th U.S. Infantry Regiment from Virginia, to help bring peace to Washington. Wright, a West Point graduate, was an experienced officer, having fought against the Seminoles in Florida and in the Mexican-American War, where he was wounded at Molino del Rey and brevetted to the grade of colonel. Wright had also served in California with the 4th Infantry, and had carried out missions in the Northwest; hence, he knew something of the territory. He was tough and decisive: one veteran of the 1858 campaign wrote, “No worry, confusion, or doubt was ever discernible in our commander.”

Wright had been sympathetic to the plight of the native tribes. In 1856, although he had hanged nine Indians implicated in an attack on Fort Cascades on the Columbia River, he had also protested that citizen militias were little more than gangs preying on innocent natives. He had publicly lamented the Indians’ susceptibility to the whites’ diseases, vices, and bullets, to the point that Governor Stevens had harshly criticized Wright for his empathy toward the Indians. Wright’s attitude clearly changed as that year progressed.

Wright had been sympathetic to the plight of the native tribes. In 1856, although he had hanged nine Indians implicated in an attack on Fort Cascades on the Columbia River, he had also protested that citizen militias were little more than gangs preying on innocent natives. He had publicly lamented the Indians’ susceptibility to the whites’ diseases, vices, and bullets, to the point that Governor Stevens had harshly criticized Wright for his empathy toward the Indians. Wright’s attitude clearly changed as that year progressed.

In 1856 the Department of the Pacific commander, Maj. Gen. John Wool, sent Wright into what is present-day central Washington State to find the killers of Andrew Bolon, an Indian agent murdered a year earlier, and to force Yakama chiefs Owhi and Kamiakin to quiet the unrest among their people. After he failed to win any concessions from the Indians, Wright departed, feeling both slighted and betrayed.

Governor Stevens cited the incident as evidence that Wool’s appeasement of the Indians was misguided. Moreover, the governor’s aggressive attitude had made him popular not only with settlers but with politicians in Washington, D.C. Under pressure, Wool resigned in March 1857. Brig. Gen. Newman S. Clarke, a veteran of the Mexican War who had led one of the first brigades ashore at Veracuz in 1847, replaced him.

Tension between settlers and Indians increased, with violent factions on each side occasionally engaging in murder, theft, and general mayhem. In 1857 Governor Stevens won election to Congress and left Washington Territory for good.

Clarke quickly moved his headquarters from San Francisco to Fort Vancouver. In addition, he ordered reinforcements from California and Oregon, accumulating more than 2,200 troops, one-sixth of the entire United States standing army, in forts along the Columbia. In May 1858, Lt. Col. Edward Steptoe decided to march 200 miles from Fort Walla Walla to Fort Colville. Settlers in the Colville area, he believed, feared “their lives and property [were] in danger from hostile Indians.”

On the trip north he also wanted to investigate the murder of two settlers, as well as reports that Palouse Indians had stolen horses and cows. While Steptoe had anticipated occasional skirmishes with warriors from the weak and normally disorganized Palouse tribe, he did not realize that hostile factions of the Spokane, Coeur d’Alene, and other tribes had joined them.

On May 17, while Steptoe’s force of 158 was marching through eastern Washington Territory, nearly a thousand Indians attacked them. When Steptoe retreated, the Indians gave chase, killing five soldiers and two well-regarded officers. Late that afternoon Steptoe’s men gathered on a knoll and formed a barricade with their pack train. The warriors surrounded the soldiers, in no hurry to finish them off. After dark, dozens of campfires flickered around the ridge while Indians drummed, sang death songs, and fired guns.

After the day of fighting, each of Steptoe’s men had just three rounds remaining. They hugged the earth and waited for the onslaught, many intending to save their last bullets for their own heads. Then, rallied by his officers, Steptoe decided to attempt an escape. The troops buried their dead, along with the two howitzers, and lashed the wounded to their saddles. At 10 p.m., Steptoe led his mounted soldiers from the site. They skidded down a hillside and waded across a stream, somehow managing to pass through a gap in the Indians’ circle, and then galloped south. When the Indians rushed the hill at midnight, expecting to slaughter the entire force, they found it abandoned.

After the day of fighting, each of Steptoe’s men had just three rounds remaining. They hugged the earth and waited for the onslaught, many intending to save their last bullets for their own heads. Then, rallied by his officers, Steptoe decided to attempt an escape. The troops buried their dead, along with the two howitzers, and lashed the wounded to their saddles. At 10 p.m., Steptoe led his mounted soldiers from the site. They skidded down a hillside and waded across a stream, somehow managing to pass through a gap in the Indians’ circle, and then galloped south. When the Indians rushed the hill at midnight, expecting to slaughter the entire force, they found it abandoned.

That night and the next day the soldiers rode 85 miles, finally reaching a friendly Nez Perce camp on the Snake River. One wounded man died during the ride, and they left another, too injured to continue, along the trail with enough bullets to kill a few Indians and then himself.

Steptoe’s defeat reverberated across the country. President James Buchanan and Commander in Chief of the Army Winfield Scott were incensed at the Indians, as well as at Steptoe. Colonel Wright and General Clarke, however, directed most of their anger at the Indians, since they had attacked while Steptoe’s force was in retreat.

Two weeks after the Indians defeated Steptoe, Wright wrote to Clarke, suggesting a thousand soldiers might be needed to “signally chastise them for their unwarranted attack on Colonel Steptoe.” Clarke authorized most of the force Wright had requested, telling the colonel, “You will attack all the hostile Indians you may meet, with vigor; make their punishment severe, and persevere until the submission of all is complete.”

Colonel Wright took nearly two months to assemble troops and equipment. On August 25, 1858, his force departed from the newly constructed Fort Taylor—named for one of the officers killed in the Steptoe battle. The column consisted of 680 army regulars (190 dragoons, 400 infantrymen, 90 in the rifle brigade), 100 civilian support personnel, and 700 horses and mules. There were also 33 friendly Nez Perces, 3 as scouts and the other 30 prepared to fight, and all dressed in army uniforms to distinguish them from the hostiles.

Wright had assembled a capable group of fighting men. During the coming American Civil War, 17 of the officers in the 1858 expedition became generals; 12 for the Union, 5 for the Confederacy. There was still the possibility of embarrassment, though defeat was less likely, given the size, training, and modern weapons of his force.

By August 31, five days after leaving Fort Taylor, Wright’s command was exhausted. They had marched more than 120 miles across the steep, dry hills of eastern Washington Territory, through intense heat, suffocating dust, a severe thunderstorm that wrecked some of their gear, and smoke from grass fires the Indians set, trying to stampede the pack train. They were deep in Spokane territory, 15 miles southwest of the present-day city of Spokane.

Earlier that day, the rifle companies had repulsed an attack by a small force of Indians that had tried to ignite the prairie grass behind the pack train. When that failed, the Indians approached the wagons, firing a harmless volley of musket balls and arrows before disappearing into the great dunes of the Palouse. As the troops made camp, they noticed horse-mounted warriors gathering on a hill two miles away. Between the two forces lay one large lake and three smaller ones. At sunrise the soldiers began preparing for battle, making sure their weary horses had their fill of oats and water. By 6 a.m. enough sunlight had seeped over the distant Selkirk Mountains to alert them that the number of braves had grown during the night.

Meanwhile the Nez Perce scouts were out assessing the Indians’ strength. They reported that in addition to the warriors on the hill, the plain on the opposite side was covered with horse-mounted warriors whom they identified as Spokanes, Coeur d’Alenes, and Palouses. From Indian accounts we know the braves were feeling confident, particularly because Wright’s army didn’t have an easy avenue of escape. Dandy Jim, one of the Indian combatants, said of Wright’s men: “They appeared to be hunting a fight, but we felt sure they were ours.”

At 9:30 Wright moved out. He deployed two squadrons of the 1st Dragoons under Brevet Maj. William N. Grier, four companies of the 3rd Artillery commanded by Capt. Erasmus D. Keyes, two rifle battalions of the 9th Infantry under Capt. Frederick Dent (Ulysses Grant’s brother-in-law), a mountain howitzer company commanded by Lt. James L. White of the 3rd Artillery, and the friendly Nez Perces. The remaining forces, including a howitzer company, were left to guard the pack train.

As Colonel Wright approached the base of the hill, he ordered Major Grier to circle the cavalry around the north and east sides. Wright and the main force started up the west side, along with the Nez Perces. The infantry, climbing the hill, and the dragoons below them, formed two sides of an open claw designed to close on the enemy, crushing any they could, and forcing the remainder to join the other warriors in the open.

During the climb, Wright received a message from Grier that some 500 Indians were waiting in the plains to the north and east. Wright accelerated his ascent, wanting to gain a vantage point from which he could direct the battle. When the troops reached the top, they found that the Indians that had been on the hill had descended and taken cover behind trees and rocks.

From the summit, Lt. Lawrence Kip described the scene: “Every spot seemed alive with the wild warriors we’d come so far to meet. They were in the pines on the edge of the lakes, in the ravines and gullies, on the opposite hillsides, and swarming over the plain. Mounted on their fleet, hardy horses, the crowd swayed back and forth, brandishing their weapons, shouting their war cries, and keeping up a song of defiance.”

At the top of the hill, Captain Keyes ordered several companies to deploy as skirmishers, which they did with enthusiasm, shooting accurately. Dandy Jim later recalled “as soon as the soldiers got close enough to us they opened fire with their guns at once, point-blank. Indian flesh and blood could not stand it. We broke in utter confusion and fled.”

The infantry pushed the enemy farther down the hill, and Major Grier urged his dragoons to charge. Lieutenant Kip noticed the men who had served under the two officers killed in the Steptoe expedition: “Taylor’s and Gaston’s companies were there, burning for revenge, and soon they were down on them. We saw the flash of their sabers as they cut them down. Yells and shrieks and uplifted hands were of no avail.”

The Battle of Four Lakes soon became a rout. After the dragoons aggressively charged onto the plain, Indian weapons were no match for the army. These troops carried new Springfield .58 caliber rifled muskets that fired minié balls—the first time these had been used in battle. The dragoons used Sharps carbines, which were effective from 500 yards or more. Instead of engaging in close fighting, as the Indians preferred, the troops began firing accurately far beyond the range of the Indians’ smoothbore muskets and bows and arrows.

Still, even with their superiority in weaponry and training, it took nearly four hours for the dragoons to chase away the last of the defenders, pushing them northeast into a pine forest four miles away. Wright’s only casualty was a horse, while estimates of Indian casualties varied from 50 to 100, with the same number of their horses killed or injured.

The troops’ spirits remained high for several days as they rested in camp. Meanwhile, the Indians sent messengers to surrounding tribes, calling for reinforcements, preparing for the next battle, though the clash that followed was anticlimactic.

Four days later, on the morning of Sunday, September 5, Wright’s men broke camp and headed north toward the Spokane River. After marching for an hour, they spotted Indians moving parallel to the pack train, their numbers steadily increasing. On the right, Kamiakin led the Yakamas and Palouses; Coeur d’Alenes gathered in the center; Spokanes grouped on the left. There appeared to be more Indians here than in the first battle, far in excess of 500.

The Indians torched the prairie grass, trying to panic Wright’s pack animals. Although the soldiers were quickly enveloped in smoke, instead of having them fall into defensive positions, Wright ordered a charge. The dragoons led the way through the smoke, firing away. The Indians, surprised by their boldness, quickly scattered to get out of rifle range. The howitzers were particularly effective, killing several Indians with single blasts, and wounding Yakama chief Kamiakin. Skirmishes covered 14 miles, taking up much of the day.

The fight, later referred to as the Battle of Spokane Plains, continued until after 5 that evening, when Wright’s force reached the Spokane River. By then the soldiers had traveled 25 miles, fighting more than half the way. When they finally set up camp along the Spokane River, they were parched and weary but jubilant, in part because, once again, there had been no fatalities, although one man was injured.

Wright had proven the military superiority of his force, and now he was determined to convince the Indians never to oppose him again. Over the next month he would ensure the Indians’ obedience—and his own infamy.

On September 7, the American troops began marching east along the north bank of the Spokane River, passing the falls in what is the center of present-day Spokane. That afternoon Spokane chief Garry approached Wright to talk peace. It was a one-sided conversation in which Wright told the chief that his tribe must submit. If they resisted, he said, “war will be made on you this year and the next, until your nations shall be exterminated.” Wright ordered the chief to spread this message throughout the tribes in the region.

Later that day nine more Indians came in to parley. Soldiers recognized two: Polatkin had been a leader in the two battles, and Jo-hout was a brave suspected of being involved in killing two miners near Fort Colville, one of the incidents that preceded Steptoe’s ill-fated foray. Suspicion was enough for Wright and, setting a pattern he would follow over the next month, he ordered Jo-hout hanged. His troops used a wagon carrying surveying equipment as a scaffold. Polatkin was held as a hostage. The next day the army continued its advance upriver toward Washington’s present-day border with Idaho. Along the way, the soldiers set fire to Indian lodges and grain storehouses.

That same day, the soldiers captured about 900 horses, a herd possibly belonging to Chief Tilcoax of the Palouse. After a discussion with his officers, Wright ordered most of the herd killed. The troops selected some for the army’s use, but soon realizing the untrained horses would be useless on the march, they decided to kill them, too.

A number of horses did escape. For the rest, the soldiers built a corral, gathered the animals in groups, and shot or clubbed them to death. It took two days to finish them off; according to Keyes, the final death tally was 690. “Towards the last,” he wrote, “the soldiers appeared to exult in their bloody task; and such is the ferocious character of men.”

Indians watching from a distance were devastated. What kind of enemy destroyed innocent, sacred creatures? According to Captain Keyes, Wright, ever the shrewd tactician, had precisely understood the impact such a slaughter would make on the Indians. The carcasses rotted into piles of bones, a lasting commemoration of the slaughter.

On September 11, Wright and his soldiers continued east, bound for the Coeur d’Alene mission in present-day northern Idaho, a rough trek of 40 miles from what quickly became known as Horse Slaughter Camp. Along the way, the soldiers continued to burn native lodges and food supplies. “Desolation marked our tracks,” Keyes wrote.

Wright’s demeanor remained steady and focused. In a September 15 letter to General Clarke, he described the damage and revealed his thinking: “900 horses and a large number of cattle have been killed or appropriated to our own use; many houses, with large quantities of wheat and oats, also many caches of vegetables, kamas [bulbs], and dried berries have been destroyed. A blow has been struck which they will never forget.”

On September 17, a treaty council at the Coeur d’Alene mission ended peacefully, with the Coeur d’Alenes relieved the terms weren’t harsher. The Indians were to return property they had stolen; turn over the men who started the attack on Steptoe; and had to turn over a chief and four other men, with their families, to be held as hostages. All white people were to be given free passage across Indian lands, and the Coeur d’Alenes were to allow no hostile Indians on their land. If these provisions hadn’t been violated after a year, the hostages would be released.

The mission’s Father Joseph Joset had already agreed to use his influence to gain the tribe’s acquiescence, requesting that Wright treat the tribe leniently in return. During their stay at the mission, the Indians and soldiers spent time together, trading shirts and blankets for moccasins and bows and arrows.

But at least one observer was unmoved by the friendly exchanges. “As soon as the stream of population flows up to them,” Kip wrote, “they will be contaminated by the vices of white men, and their end will be that of every other tribe which has been brought into contact with civilization.” In fact, Wright was simply being what one historian has called “a good dog of war,” docile and attentive while treaties were being created, but aggressive and even hostile once signatures were on paper. The Indians promptly gave Wright a new name: Two Tongues.

On September 22, Wright’s army marched 18 miles across rolling hills studded with pine trees, making camp at Smyth’s Ford on Latah Creek, 25 miles south of present-day Spokane. As at the Coeur d’Alene council, Wright depended on Father Joset to persuade the Spokanes that meeting him at the creek was in their best interest. Hundreds of Indians had already gathered there. In addition to the Spokanes, there were representatives from at least six other tribes, all nervous after hearing of Wright’s march up the Spokane River and Jo-hout’s hanging. But Wright had promised Chief Garry that “if they did as [he] demanded, no life should be taken.”

On the morning of September 23, the assembled chiefs quickly agreed to a treaty with essentially the same provisions as the one agreed to by the Coeur d’Alenes a few days earlier. Wright ordered the chiefs to acknowledge their crimes, apologize for what they’d done, and thank him for his leniency. But once the treaty was signed, Wright changed back into a punishing invader. That evening an unexpected visitor arrived in camp: Chief Owhi of the Yakama, the man who, in 1856, had snubbed Wright in the Yakima Valley.

Owhi wanted to talk peace, but Wright ordered the “semi-hostile” placed in irons. Owhi’s cause was hurt by the fact that his son, Qualchan, was an infamous warrior who had been involved in attacks on white settlers. The son was also thought to have taken part in murdering Indian agent Bolon in the Yakima Valley, though this was later disproved. Two Indian messengers were sent to find Qualchan and give him a message: If he didn’t show himself before Wright within four days, his father would be hanged.

In his journal, Lieutenant Kip wrote, “An Indian war is a chapter of accidents.” One of those accidents occurred the following morning. Looking up the canyon, Captain Keyes noticed riding toward the camp “two braves and a handsome squaw.” The Indians were wearing a “great deal of scarlet, and the squaw sported two ornamental scarves, passing from the right shoulder under the left arm.” The men held rifles, and one carried a tomahawk covered with ornaments.

Wright couldn’t believe his luck: One brave was Qualchan. The messengers hadn’t yet found him; rather, he had come on his own, hoping to talk peace. Keyes wrote, “[Qualchan] was a scion of a line of chieftains; his complexion was not so dark as that of the vulgar Indian, and he was a perfect mould of form. His chest was broad and deep, and his extremities small and well shaped.” Wright spoke to him, showing him his father, Owhi, bound in chains. Suddenly, Wright ordered his men to seize Qualchan. “He had the strength of a Hercules,” wrote Keyes. It took six men to hold him and tie his hands and feet, despite an unhealed bullet wound in his abdomen.

Within minutes, Wright ordered his men to hang Qualchan. They promptly complied, looping a rope over a pine bough for the job. In a letter to General Clarke, Wright’s description of the event consisted of one sentence: “[Qualchan] came to me at 9 o’clock this morning, and at 9¼ a.m. he was hung.”

Wright’s snap justice bothered many in his force. Kip wrote that there was “much comment among the officers and men.”

After all, Owhi had come voluntarily to talk with the commander, but he had been bound in chains and Qualchan had been hanged without a trial. After the Qualchan episode, the tribes were angry, but more important, terrified, just as Wright intended. His strategy of methodically destroying their spirit was succeeding.

Later that same day, members of the Palouse and Walla Walla tribes rode into camp, probably unaware of Qualchan’s fate and the imprisonment of Owhi. Wright talked with the new visitors, and later said he had conducted a “thorough investigation” (which involved asking a few questions).

Wright ordered nine braves put in irons. Six more were identified as participants in the fight against Steptoe, and Wright immediately ordered them hanged. There were only three ropes prepared, but the colonel didn’t want to wait for more, so half the group had to watch while their comrades were executed.

While the ropes were being adjusted around the necks of the second trio, “they danced and hopped around, singing their death songs,” wrote one soldier who was there.

Wright’s army left Latah Creek, which was immediately dubbed Hangman Creek, on September 26, heading back to Fort Taylor on the Snake River, where they planned to rest before returning to Fort Walla Walla. On September 27 they met with a minor Palouse chief, Slow-i-archy, and a group of his followers. The chief wanted to talk peace, but Wright once again shackled the leaders. Then, after gathering some 100 Palouses at his camp, he took hostages and told the assemblage that if they remained peaceful he would come back in a year and conclude a peace treaty with them. If they were hostile to whites, “I’ll hang them all, men, women, and children,” Wright told them. To emphasize his message, Wright brought out the prisoners he had collected along his route and put four on a wagon positioned under a tree. The four were hanged in full view of the assemblage, their bodies squirming at the ends of ropes while Wright continued talking to the group as if nothing was happening. He had made his point; settlers would have no more trouble with the Palouse.

On October 1, the army reached Fort Taylor, where the commanding officer, Keyes wrote, had prepared for the men a feast of “bunch-grass fed beef (the best in the world), prairie chickens, vegetables, and a basket of champagne, which disappeared down our thirsty throats like water in the sand.” A couple days later, while the party was en route from Fort Taylor to Fort Walla Walla, soldiers shot and killed Chief Owhi, supposedly as he was trying to escape.

Wright’s army and 33 hostages reached Fort Walla Walla on October 5—60 days after leaving. The military’s only fatalities on the expedition had occurred on August 30, when two artillerymen died after eating the roots of what was identified then as “wild parsnips,” probably water hemlock.

Even after the campaign ended, Wright’s bloodlust was not quite quenched. On October 9, he called a council of Walla Walla Indians. He asked any of them who had been in the recent battles to stand; 35 did so. Selecting four, he ordered them immediately hanged.

During September and early October 1858, Wright had hanged a total of 16 Indians. None had a trial extending beyond a few questions. Certainly, both whites and Indians had engaged in far more lethal violence during the 19th century, yet few campaigns, if any, matched Wright’s careful planning, precise execution, and callousness. Rather than subdue the tribes with a bludgeon, he used a scalpel, steadily severing them from their land, animals, food supplies, and families—all foundations of their spiritual beliefs and well-being. Many more Indians died of starvation that winter, particularly the very young and very old, from the destruction of their food supplies.

As word of what Wright had done spread across the country, there were expressions of sympathy for the Indians, but Wright was neither punished nor reprimanded for his highhanded ways. In fact, General Clarke officially commended him for the “zeal, energy, and skill” with which he led his punitive expedition, and he would later be promoted to the rank of brigadier general in the Union army.

“I have treated these Indians severely,” Wright wrote Clarke on completing the expedition, “but they justly deserved it all. They will remember it.”

And indeed, during Wright’s lifetime, there were no more Indian uprisings in the Columbia Plateau.

MHQ

This article was first published in MHQ, Spring 2010.