Under cover of darkness on the night of March 3, 1836, a courier departed the besieged Alamo with a bundle of letters, including another desperate plea for reinforcements. He was reportedly the last messenger to leave the doomed garrison. By sunrise on March 6 co-commander Lieutenant Colonel William Barret Travis and some 200 fellow Texian defenders lay dead after a defiant 13-day stand against thousands of Mexican soldiers under General Antonio López de Santa Anna.

Writers have since cranked out countless stories about the brave deeds reportedly done that day, leaving historians the monumental task of sifting fact from layers of myth. Attempting to reconstruct just what took place inside the Alamo’s walls during the siege presents an even greater challenge. Prior to the siege, numerous defenders wrote letters to loved ones back in the United States. Tennessean Micajah Autry, Kentuckian Daniel William Cloud and Pennsylvanian David P. Cummings are among those who wrote glowing accounts of their journey into the Mexican province of Texas. Their words would foreshadow their deaths at the old mission on the outskirts of San Antonio de Béxar.

Yet the accounts of only a few survivors and a handful of correspondence written during the siege, including two letters by Travis dated to March 3—a note to his son’s caretaker, David Ayers; and a request for a parley between Mexican army commanders and James Bowie, commander of the Alamo volunteers—survive to provide scant, yet precious details of the garrison’s final days and hours. Thus the complete March 3 bundle of letters represents a potential trove for Alamo researchers. Those missives record the final, intimate thoughts of a number of Alamo defenders, who by then clearly understood the peril of their predicament. So in the spirit of historical diligence, the question arises: Do any of those letters still exist?

The evidence is tantalizing.

‘He came into possession of an old box of letters years ago, several of which were written by Alamo defenders. The letters were supposedly still in the possession of his family’

Retired U.S. Marshal Bob Anderson of Harlingen, Texas, is a matter-of-fact kind of man. He had to be. Anderson’s assignments were often a matter of life and death, particularly for those he guarded in the U.S. Federal Witness Protection Program. He once guarded John Dean, the former White House counsel who pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice and turned state’s evidence in the Watergate scandal. Dean lived in a safe house typically reserved for witnesses against the mafia and spent his days providing information to Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox. Anderson had a front-row seat to history.

Naturally, Anderson’s job as a U.S. marshal also required him to sniff out the occasional horse manure. Perhaps that’s why his Alamo story is, if nothing else, intriguing. Several years ago while on a drive through the Rio Grande Valley between McAllen and Brownsville, Texas, Anderson encountered a traveling carnival worker who introduced himself as William Linn (ironically or intentionally, a name shared by an Alamo defender from Massachusetts). Anderson, whose family is descended from Alamo defender Andrew Kent, was wearing an Alamo Defenders Descendants Association jacket, and that sparked a conversation with Linn.

“He told me his grandfather was the former postmaster at Ooltewah, Tenn.,” Anderson recalled, “and he came into possession of an old box of letters years ago, several of which were written by Alamo defenders. The letters were supposedly still in the possession of his family.”

As the carny told it, the letters had been left at that post office in Tennessee’s Hamilton County. At the time few area residents were literate, Linn explained, and his grandfather told him that after he’d read the Alamo dispatches to the addressees, they returned home. Given the emotional ties such letters likely provided, it’s hard to imagine family members would leave them behind. That said, at least 32 Alamo defenders had Tennessee connections, including William Mills, who was born in Hamilton County (Chattanooga). Thus it’s not a stretch to believe a batch of letters from the Alamo may have reached Tennessee in the weeks after the battle.

Linn eventually faded into the crowd, and Anderson’s subsequent attempts to find him failed.

Could Linn’s family hold some of the missing March 3 batch of Alamo letters? Or was he just another carny spinning a good yarn? “I believed him,” Anderson said bluntly. “I remember thinking, Who would come up with this kind of story out of nowhere? He had too many specific details on the spot.”

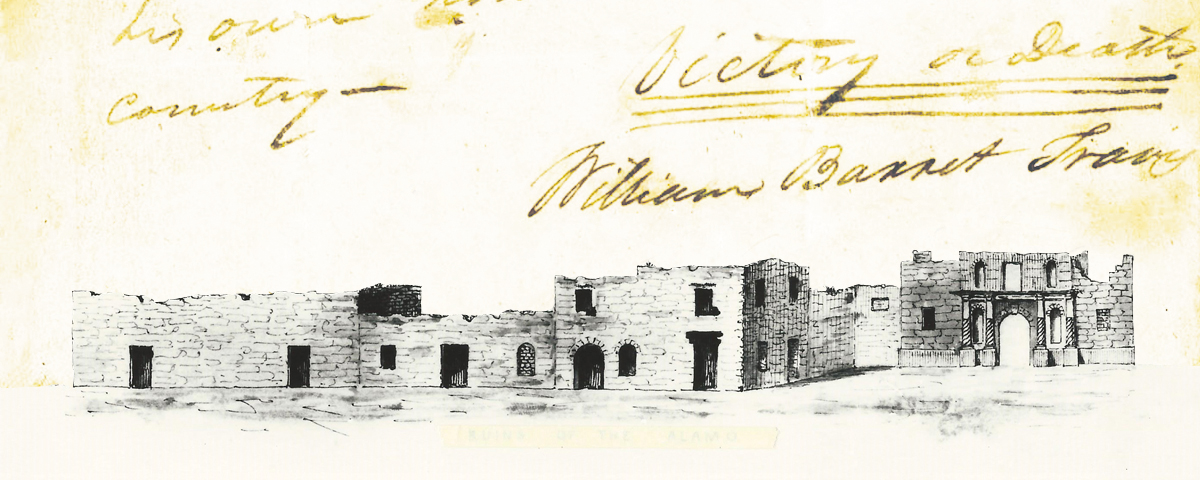

While the veracity of Linn’s story remains in doubt, what is certain is that a bundle of letters did leave the Alamo on March 3, 1836, and at least three bearing that date successfully reached their intended destinations. Travis himself wrote two of those letters—one to “the president of the [Texas constitutional] convention,” Richard Ellis (published in the March 12 San Felipe Telegraph and Texas Register), the other to a friend, thought to be Jesse Grimes (published in the March 24 Telegraph and Texas Register). Both provide important military details regarding the besieged garrison. In the first letter Travis described enemy entrenchments and firepower and how the spirits of his men were “still high” despite their having witnessed “at least 200 shells” hammer the compound, albeit without “a single man” suffering injury. Travis also noted the recent arrival of 32 volunteers from Gonzales, as well as the arrival of courier James Butler Bonham that morning. The letter to Grimes offers similar details and yet another stern plea for reinforcements. In fiery words that have defined Travis as a tragic hero of Texas history, he concludes, “If my countrymen do not rally to my relief, I am determined to perish in the defense of this place, and my bones shall reproach my country for her neglect.”

A third letter dated March 3 was penned by Alamo defender Willis A. Moore, writing to family members in Raymond, Miss. Moore wrote three letters from San Antonio, including two pre-siege letters, dated Dec. 28, 1835, and Jan. 13, 1836. Twenty years after the battle Moore’s heirs presented all three letters to the Texas General Land Office as evidence of Moore’s service to Texas and the land he was therefore due, but none has surfaced publicly.

An undated fourth letter—written by Travis to friend David Ayers—is also generally thought to have been sent March 3 from the doomed garrison and is arguably the most heart-wrenching missive of all known Alamo letters. Travis reportedly wrote it in great haste for his 6-year-old son, Charles, as the last courier prepared to bolt from the garrison. The letter—last seen in 1852—was scrawled on a scrap of yellow wrapping paper, torn and ragged to the point its date was unreadable, and delivered by a courier who brought news that Travis had answered the summons to surrender with a cannon shot, and his flag still waved from the walls. The Alamo co-commander’s final words regarding his son are haunting:

Dear Sir: Take care of my little boy. If the country should be saved, I may make him a splendid fortune. But if the country should be lost, and I should perish, he will have nothing but the proud recollection that he is the son of a man who died for his country.

Travis seldom varnished his thoughts, thus another missive reportedly written by him and delivered with the final March 3 bundle remains the holy grail of all Alamo letters. The addressee was his fiancée, Rebecca Cummings. Unfortunately, its contents have never been revealed and may forever remain a mystery. According to the remembrances of Angelina Eberly, a San Felipe boardinghouse operator, the letter to “Miss Cummings” arrived in town on March 6, the day the Alamo fell. Years later Eberly related her account of its memorable arrival to Mary Austin Holley, whose papers are housed in the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin. One can only imagine what Travis—a man of the Romantic era—related to his fiancée in a private letter as he stood on the doorstep of eternity.

Cummings may have discarded Travis’ missive after marrying attorney David Young Portis in 1843, as a letter from an old flame might not serve a marriage well. Of course, that is mere speculation. A potentially interesting footnote to the Travis-Cummings romance is that Rebecca may be buried in the Odd Fellows Cemetery in San Antonio, depending on whose genealogy one believes. Cummings died in either 1872 or 1874. At the time that hilltop cemetery offered an unobstructed view of the Alamo. Coincidence? Perhaps.

The March 3 batch of letters from the Alamo spurred a range of emotions across the Texas frontier. In his journal entry of March 6 Virginian William Fairfax Gray, who was in Washington-on-the-Brazos to observe the constitutional convention, noted, “This morning, while at breakfast, a dispatch was received from Travis, dated Alamo, March 3.” Gray was referencing Travis’ letter to Ellis, who read the missive aloud to the gathered delegates. At first they debated whether the Alamo was truly under siege. Doubts festered. Ellis then gathered the delegates together to assess the authenticity of the letter. In a document preserved in the Audited Military Claims collection at the Texas State Library in Austin, eyewitness Lancelot Abbotts, a printer and clerk from San Felipe, recounted the frantic scene:

The veracity of the courier who carried it to Washington, and the authenticity of the signature of Travis, were questioned by some members of the Convention and by citizens. Two or three of the members were aware that I knew well the handwriting of Col. Travis, and a Committee of the Convention waited on me to ascertain my opinion on the matter. I unhesitatingly pronounced the dispatch (brief as it was) to be the handwriting of the brave Travis.

A public meeting was called for the purpose of enlisting volunteers for the relief of the Alamo. At this time there was living in Washington a doctor by the name of Biggs, or Briggs, who was a big, burly, brave Manifest Destiny man. He made a speech, in which he declared his unbelief in the dispatch and the utter impossibility of any number of Mexicans to take the Alamo when defended by near 200 men.

Travis’ letter to Ellis, of course, was as real as Santa Anna’s ability to overpower the Texians defending the Alamo’s walls. The fact that a courier successfully slipped through enemy lines with a saddlebag of letters is in itself a miracle. Mexican patrols were everywhere.

One persistent story identifies John William Smith as the Alamo’s last courier, although evidence found by the late Alamo historian Thomas Ricks Lindley suggests someone else might have carried the March 3 letters through the Mexican lines. Lindley cited Alamo defender James Lee Ewing’s probate, in which Smith testified two years after the battle. It bears the following notation: “He [Smith] left him [Ewing] in the Alamo on the Friday night previous to its fall.” Friday night was March 4, 1836.

So if Smith didn’t leave until March 4, who did carry the last known batch of letters beyond the garrison gates? As many as 22 men have been identified as Alamo couriers with varying degrees of credible evidence since the famed last stand of 1836. There simply isn’t enough information to know for certain who that fearless courier might have been.

The historical record is clear that William Bull carried a batch of the Alamo’s final dispatches 110 miles from Gonzales to the constitutional convention at Washington-on-the-Brazos. He arrived on the morning of March 6 and is the courier who carried Travis’ letter to Ellis and whose “veracity” certain delegates and citizens called into question that day. Joseph D. Clements, a prominent member of Gonzales’ defiant militia, had paid Bull $5 for his troubles.

Evidence also indicates the Alamo’s final batch of letters were split by March 6. Gray’s March 6 journal entry at Washington (noting the arrival of Travis’ letter to Ellis) and Eberly’s recollection of March 6 at San Felipe (noting the arrival of Travis’ letter to Cummings) support that conclusion. The split might have occurred at Gonzales or at Moore’s Ferry on the Colorado River. Regardless, the letters were divided, and another unknown courier was called into service.

A petition submitted decades later to the Texas Legislature lends additional weight to this scenario. In it W.D. Grady, then employed as a printer for the Telegraph and Texas Register in San Felipe, recalled when letters from Travis (perhaps the one written to Cummings) and David Crockett arrived from the Alamo. Grady doesn’t mention the arrival date. Were these missives part of the March 3 bundle? As with the letter Travis reportedly wrote to Cummings, the Crockett letter Grady cited has never surfaced and would be worth a fortune if still in existence.

Such a prospect is not unheard of, even in Alamo circles. Several years ago a portrait of Alamo defender Joseph G. Washington surfaced, having been in family possession in Kentucky since his 1835 departure for Texas. The importance of its discovery can’t be overstated. Until the emergence of the Washington painting, only three Alamo defenders were known to have sat for portraits in their lifetime (Crockett, Bowie and Dr. Amos Pollard).

A rare letter from an Alamo defender could also resurface. During the 1960s and ’70s unscrupulous visitors to various state and county archives made off with thousands of Texas Republic–era documents, as chronicled in W. Thomas Taylor’s 1991 book Texfake: An Account of the Theft and Forgery of Early Texas Printed Documents. At least 846 historic papers vanished from the Texas State Archives alone. A few brazen souls even attempted to auction off such treasures. Other documents undoubtedly turned up on the black market and remain in private hands.

The letter of March 3, 1836, that Alamo defender Willis Moore wrote might fall under this category. Moore’s heirs presented the letter to the Texas General Land Office on Sept. 22, 1856, but it has since gone missing from his file there. State officials may have returned it and the two other letters in his file to Moore’s executor. Perhaps they were misfiled. Or maybe they were stolen.

If still in existence, his letter and the other missing missives would be invaluable to the Alamo story, for they contain words that whisper from the grave. WW

Ron J. Jackson Jr. is from Binger, Okla. He is the co-author, with Lee Spencer White, of both the 2015 book Joe, the Slave Who Became an Alamo Legend and the article “The Legend of Alamo Joe,” in the February 2016 Wild West. For further reading he recommends Alamo Traces, by Thomas Ricks Lindley; The Alamo Reader, by Todd Hansen; and Texfake, by W. Thomas Taylor.