[dropcap]D[/dropcap]ecember 16, 1944, was a dangerous day for Allied forces in Europe. The Wehrmacht sprung one of the war’s largest strategic surprises when it launched two Panzer armies and an infantry army into the thin American defenses in the Ardennes Forest. The next day the U.S. Third Army commander, Lieutenant General George S. Patton, sat in his headquarters writing a letter to a retired major general living in New York’s Adirondack Mountains: “Yesterday morning the Germans attacked to my north in front of the VIII Corps of the First Army,” Patton told Fox Conner. “It reminds me much of [the German attack on] March 25, 1918, and I think it will have the same results.”

Though Patton misremembered the date—it was actually March 21, 1918—his prediction proved accurate. Like Operation Michael 26 years earlier, the Ardennes offensive was Germany’s desperate attempt to end the war with a single knockout punch. And like its predecessor, the offensive failed to reach its objective. On December 19, 1944, Allied Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered Patton to turn his Third Army 90 degrees on the battlefield and counterattack north, into the southern shoulder of the German penetration known as “The Bulge.” Seven days later, Patton’s troops pushed into Bastogne to relieve the encircled 101st Airborne Division.

Why did Patton spend time writing to an obscure old soldier, given the crisis? The answer is that more than anyone else, Conner was responsible for placing Patton and Eisenhower at that point in history. He was also influential to another important wartime figure: U.S. Army chief of staff General George C. Marshall. Although Conner retired from the army a year before World War II began, his mentorship of these senior American generals when they were young officers left an imprint on the battlefield—and made Major General Fox Conner a significant contributor to the Allied victory.

Today, the officer whom Eisenhower called “the ablest man I ever knew” remains a historical enigma. Conner wrote no memoirs and ordered all his papers and journals burned after his death. Only 28 letters survive. Most of what can be determined about Conner derives from the writings of his three famous World War II protégés and of his old boss, General of the Armies John J. Pershing, under whom Conner served in World War I in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). “I could have spared any man in the AEF better than you,” Pershing told Conner.

Born at Slate Springs, Mississippi, in 1874, Conner graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1898. During his final year at West Point, Conner’s company tactical officer was First Lieutenant Pershing. Conner was commissioned in the artillery and, during the years prior to the First World War, established a reputation as one of the U.S. Army’s leading gunnery experts and an early proponent of new fire control technologies.

In 1902, he married Virginia “Bug” Brandreth, whose father made a fortune selling a vegetable digestive aid called Brandreth’s Pills, and whose family owned a huge spread—Brandreth Park—in the Adirondacks. Conner graduated from the U.S. Army General Service and Staff College (later renamed the Command and General Staff College) in 1906; two years later he graduated from the U.S. Army War College and went on to serve as an instructor at both newly established schools. As a captain at the War College, Conner frequently found himself lecturing to majors and colonels. (One of his students, Colonel Hunter Liggett, would become what many military historians consider the best American general of World War I.)

In 1911, Conner went to France as an exchange officer with a French artillery regiment—an assignment that paid off a few years later. By October 1913, he was back in the United States and on a train to Fort Riley, Kansas, when he and Bug met a charismatic lieutenant, George S. Patton, and his wife, Beatrice. Sharing mutual passions for horses, hunting, and deep-sea fishing, the two struck up an immediate friendship, as did their wives, both from socially prominent families.

During Pershing’s Punitive Expedition into Mexico in June 1916, Conner was the escort officer for General Tasker H. Bliss, the army’s assistant chief of staff, as they traveled 150 miles into Mexican territory to Pershing’s headquarters. Following the meeting, Pershing’s aide, Patton, escorted Bliss and Conner back to Columbus, New Mexico.

When America entered World War I in April 1917, Conner—then a lieutenant colonel— was one of the few officers in the U.S. Army who had experience working with the French. He and Patton continued to cross paths, serving together the following month as members of the advance party that sailed to Europe with Pershing to establish the American Expeditionary Forces to fight in Europe. On September 1, Conner and Patton went to Chaumont, France, to set up the AEF’s general headquarters.

American units continued to pour into France until early 1918; by then, Conner was a full colonel and chief of the AEF’s operations section, making frequent visits to the front lines. One such trip in February 1918 almost ended his career. As Patton wrote to Beatrice, “Col. Fox Conner got wounded last week. They were inspecting and came to a part of the trench full of water. They climbed out on the top and ran along to avoid the water when just as they were jumping in again a shell blew up and cut Col. C’s nose and throat. He is alright again, and will get a Wound Badge [a chevron of gold metallic thread worn on the lower right sleeve, replaced in 1932 by the Purple Heart], which is nice.”

By March 21, 1918, the AEF was still several months from committing to large-scale combat operations when the Germans struck on the Western Front—an offensive Patton would recall 26 years later at the start of the Battle of the Bulge. The U.S. First Division unleashed the first American division-sized attack of the war in late May, when it stormed German positions around the village of Cantigny.

As AEF’s chief of operations—also known as G-3—Conner closely monitored the First Division’s planning and preparations. He spent one day each week at division headquarters working closely with their G-3, Lieutenant Colonel George C. Marshall, 37, who greatly impressed Conner. After the Cantigny attack succeeded—proving to enemies and allies alike that the Americans could pull off division-level operations—he had Marshall transferred to the AEF staff as his assistant G-3.

Conner recognized in Marshall an officer whose grasp of operational planning and strategy was equal to his own. Together they developed the basic operations plan for the Saint-Mihiel Offensive—the deployment schedule, scheme of maneuver, fire and air support plans, and the logistical support for nine American divisions, totaling 550,000 troops. Conner often accompanied Pershing to meetings with the French, leaving Marshall to run the G-3 shop with Conner’s complete confidence.

In August 1918, the U.S. First Army became operational; that same month Conner was promoted to brigadier general and Marshall to full colonel. Pershing decided he would command the First Army himself, while retaining command of the AEF, but Conner advised his boss against it. When Pershing rejected his advice, Conner helped all he could by transferring Marshall to the First Army as its G-3. Marshall “knows more about the techniques of arranging allied commands than any man I know,” Conner said later. “He is nothing short of a genius.”

From September 12-15, he and Marshall coordinated the final preparations and planning for Saint-Mihiel, and for the massive Meuse-Argonne Campaign that started on September 26 and lasted until the war’s end.

On June 28, 1919, Conner attended the signing of the Versailles Treaty with Pershing. The treaty’s harsh punitive terms and the fact that the German army had been allowed to march back into Germany with its arms and colors flying appalled Conner, who later told Marshall that the treaty virtually guaranteed the Allies would have to fight another war against the same enemy, in the same place. Conner went on to dedicate the remaining years of his army career to identifying talent and grooming young officers for a war he knew was coming.

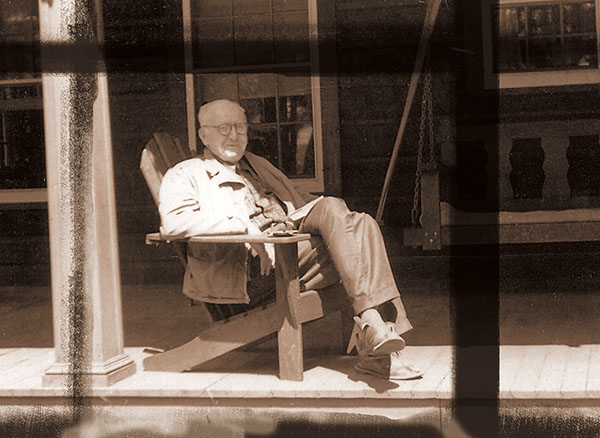

In October 1919, Conner and Marshall sequestered for three weeks at Conner’s farm at Brandreth Park to help Pershing prepare his testimony before Congress about army reorganization following lessons learned in World War I. Beginning October 31, Pershing testified for three days before a joint session of Senate and House military committees with Conner on one side of him, Marshall on the other. The pair also followed Pershing during his long inspection tour of army posts in the United States. And when Pershing became the army’s chief of staff in July 1921, Marshall was his aide.

Conner, meanwhile, was preparing to assume command in December 1921 of the 20th Infantry Brigade, based in the Panama Canal Zone. Several months before then, he paid a visit to his old friend Patton at the Infantry Tank School at Fort Meade, Maryland. Conner told Patton he was looking for a bright, young candidate to be his executive officer in Panama. Patton immediately recommended a friend also stationed at Fort Meade: Major Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The Pattons hosted a dinner for the Conners and Eisenhowers. The young officer known as Ike impressed Conner, who wanted to offer him the job. But Eisenhower was under a dark cloud. He had recently argued that in future wars, tanks would be an important force in their own right, rather than serve as mere infantry support weapons.

At the time, tanks were considered just another weapons system similar to machine guns and mortars, and the idea that they could operate as a combat arm equal to the infantry was heresy. Eisenhower’s article invoked the ire of the chief of infantry, Major General Charles S. Farnsworth, landing him at the top of Farnsworth’s persona non grata list. To get Eisenhower’s transfer approved, Conner went to Pershing. He later wrote to Eisenhower letting him know orders were forthcoming, and advised him to stop in to see Pershing’s aide—

Marshall—at the War Department to make sure everything was on track. It was likely the first time Marshall heard of Eisenhower.

Eisenhower reported to Camp Gaillard in the Panama Canal Zone in January 1922. He called the next two years under Conner his most profound period of military education. Conner recognized a great but underdeveloped talent in Eisenhower and set out to cultivate it. He introduced him to the principles of precise and methodical military staff work, and required him to produce a standard five-paragraph operations order for everything the 20th Infantry Brigade did.

He then started Eisenhower on an intense military history reading program and instructed him to discuss each book and its lessons for modern warfare in detail. Conner made Eisenhower read Carl von Clausewitz’s On War repeatedly and worked to expand Eisenhower’s intellectual horizons by introducing him to the works of Plato, Tacitus, Nietzsche, and Shakespeare—who frequently portrayed soldiers in his plays. “In describing these soldiers, their actions, and giving them speech,” Conner told Eisenhower, “Shakespeare undoubtedly was describing soldiers he knew at first hand, identifying them, making them part of his own characters.”

Drawing on his own experiences with coalition warfare during the Great War, Conner impressed upon Eisenhower three important war-fighting lessons:

1. Never fight unless you have to

2. Never fight alone

3. Never fight for long

Eisenhower knew his military career depended on completing the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The problem was how to get in. With each branch allocated only a certain number of slots every year, the competition was intense—and, in 1925, Eisenhower was still on Farnsworth’s blacklist. Conner contacted an old West Point classmate, Major General Robert C. Davis, who had been the adjutant general on Pershing’s staff in France and was now the adjutant general of the U.S. Army. Davis was responsible for, among other things, all personnel management actions, and so Conner had Davis arrange Eisenhower’s transfer to the Adjutant General’s Corps. Davis then gave Eisenhower one of the corps’ two Leavenworth slots.

Since Eisenhower had not attended the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia, however, he doubted his ability to handle the Leavenworth curriculum. “You quit worrying,” Conner wrote to him. “You are better prepared for Leavenworth than any other man that has graduated from Benning because you have had to do the work required at Leavenworth. I know; I’ve been through that school, I’ve been an instructor there.” Eisenhower went on to graduate first in his class. It certainly did not hurt that his old friend Patton had given him his notes from the previous year. However, the primary factor behind his success was Conner’s tutelage.

After Eisenhower’s graduation, Conner and Davis transferred him back to the infantry and his meteoric career took off. He went on to serve as General Douglas MacArthur’s aide and accompanied him to the Philippines. In early December 1941, Marshall—then the U.S. Army’s chief of staff—brought newly promoted Brigadier General Eisenhower to Washington as deputy chief of the War Plans Division. In a little after a year, Eisenhower was wearing four stars.

Conner’s next major assignment was as deputy chief of staff of the U.S. Army—the equivalent of today’s vice chief of staff—in 1925 and 1926. In 1927, he commanded the First Infantry Division and, in 1928, he assumed command of the Hawaiian Department and the Hawaiian Division: today’s 25th Infantry Division. One of his principle staff officers there was Patton.

Conner’s strategy for mentoring Patton was the inverse of that for Eisenhower. Patton had a piercing intellect and an unparalleled passion for the profession of arms. Rather than lighting a fire under Patton, as Conner did with Eisenhower, he frequently stepped in to prevent Patton’s aggressive and abrasive nature from damaging his career.

Patton had been stationed in Hawaii, then a U.S. territory, since 1925. Although he had been a temporary colonel at the end of World War I, Patton, like almost all officers holding temporary wartime rank, had been bumped back to his permanent rank of major when the war ended. He had started out in Hawaii as the divisional G-3, but a series of scathing evaluation reports he wrote on the training and readiness of subordinate units ruffled too many feathers. Many of the units he criticized were commanded by colonels who did not appreciate being taken to task by a mere major, regardless of what rank he held at the end of 1918. By the time Conner arrived, Patton had been reassigned to the less prestigious position of divisional intelligence officer, or G-2.

Patton did not take the downgrade well. Writing bitterly about the situation to his wife, he said the division commander, Major General William R. Smith, must have thought he made a mistake, “as he had both Floyd and Capt. Coffey tell me that it was only dire necessity which made him relieve me as G-3. Of course, he is either a fool or a liar. Probably both.”

Upon assuming command of the division, Conner managed to get Patton under control. When Patton completed his G-2 assignment, Conner wrote on his evaluation report, “I have known him for fifteen years, in both peace and war. I know of no one whom I would prefer to have as a subordinate commander.” Without Conner’s intervention and endorsement, Patton’s career may well have been over.

When Conner returned to the United States from Hawaii in 1930, General Charles P. Summerall was just finishing his tenure as chief of staff of the army. Two leading candidates were under consideration for his replacement: Conner and MacArthur. Pershing—now retired, but still a major force in U.S. Army circles—supported Conner for the job, but MacArthur got the appointment. According to some sources, Conner took himself out of the running; he hated Washington and did not want to return.

Conner went on to a series of high-ranking assignments, culminating in 1936 with command of the U.S. First Army. Two years later, he retired with little fanfare. Marshall, then less than a year away from becoming the 15th chief of staff of the army, wrote to his old mentor: “I am deeply sorry, both personally and officially, to see you leave the active list, because you have a great deal yet to give the Army out of that wise head of yours.”

As Marshall predicted, Conner did have more to give the U.S. Army. Throughout World War II, all three of his star pupils wrote to him regularly, often seeking his advice or opinion on plans in progress. “More and more in the last few days my mind has turned back to you and to the days I was privileged to serve intimately under your wise counsel and leadership,” Eisenhower wrote to Conner from London on July 4, 1942, just two weeks after being appointed Commanding General of the U.S. European Theater of Operations. “I cannot tell you how much I would appreciate at this moment an opportunity for an hour’s discussion with you on problems that constantly beset me.” During the war, classified couriers from Washington brought files of war plans—sent by Eisenhower or Marshall—up the remote gravel drive of Conner’s New York farm for his review. Conner sent the plans back accompanied by extensive notes.

Conner died on October 13, 1951, a little more than a year before his most famous protégé was elected president of the United States. Conner never wore more than two stars on his shoulders, but his three understudies accounted for a cumulative total of 14 stars. ✯