‘The Cherry Valley Massacre convinced General George Washington to launch a massive, no-holds-barred retaliatory expedition’

On the afternoon of Nov. 11, 1778, Captain Benjamin Warren cautiously led a group of soldiers out of the small fort at Cherry Valley, New York, and straight into a scene from hell. As the Patriot soldiers walked through the once-thriving farming community, they saw nothing but carnage: a man weeping over the mutilated and scalped bodies of his wife and four children; other corpses with their heads crushed by tomahawks and rifle butts; charred human remains in the smoking ruins of cabins and barns. It was, Warren later wrote, “a shocking sight my eyes never beheld before of savage and brutal barbarity.”

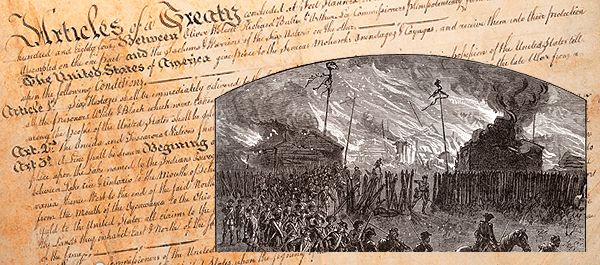

The savagery had begun early that morning, when a hundreds-strong force of Loyalist militiamen, Seneca Indians and a few British soldiers had appeared out of the fog and rain. The town and its small garrison were taken completely by surprise, and the raiders—led by Tory Captain Walter Butler and Mohawk war chief Joseph Brant—launched into an orgy of death and destruction. The fort managed to hold out, but the town and its people were defenseless. By the time the attackers withdrew, more than 30 civilians—mostly women and children—and 16 soldiers were dead and nearly 200 people left homeless. The assault soon became known as the “Cherry Valley Massacre,” and it would help convince General George Washington to launch a massive, no-holds-barred retaliatory expedition.

Their names have a romantic, almost mystical ring: Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Mohawk, Oneida, Tuscarora. But there was a time when mere mention of these tribes struck terror in the hearts of settlers along America’s first frontier. They referred to themselves collectively as Haudenosaunee (“People of the Longhouse”). They were the Six Nations of the Iroquois, and by choosing sides during the American Revolution, they ensured their own destruction. Before the war was over, Iroquois’ homes lay in ruins, their crops and orchards burned, their people freezing and starving.

For hundreds of years the tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy occupied most of what would become New York state. Their territory included the Mo-hawk Valley and the eponymous river that courses 130 miles from the Adirondacks to the Hudson. The river valley was a gateway to the West, and with the coming of the whites, it would become one of the most hotly contested grounds in North America.

In the years before the Revolution, the Iroquois tribes had developed close relationships with the British, based on commerce, war and—in some instances—intermarriage. When war threatened between Britain and its colonies, the Iroquois at first sought to remain neutral. But with prompting from British leaders, Joseph Brant (known in Mohawk as Thayendanegea) and his influential sister, Molly, soon joined with Seneca chiefs Sayenqueraghta and Cornplanter to pressure the Mohawks, Senecas, Onondagas, Cayugas and some Tuscaroras to fight alongside the British. In September 1776, over strong internal dissension, the Iroquois tribes formally and secretly agreed to side with the British; only the Oneidas and some Tuscaroras aligned with the Patriots.

The Indians who stood with the British generally fought alongside American and Canadian Loyalists. The most infamous band of Loyalists to utilize Indian allies was Butler’s Rangers—a partisan regiment formed in 1777 under Lt. Col. John Butler, a Tory from the Mohawk Valley and father to Captain Walter Butler. While focusing their activities on the New York and Pennsylvania settlements, Butler’s irregulars ranged as far afield as Virginia and Michigan. They were extremely effective and, at times, brutal. The 1778 Wyoming and Cherry Valley massacres—the bloodiest of many border fights—were largely the work of Butler’s Rangers, together with Cornplanter and Sayenqueraghta’s Senecas, Brant’s Mohawks and Indians from other tribes.

The July 3, 1778, clash in Pennsylvania’s Wyoming Valley—a stretch of the Susquehanna River in present-day Luzerne County—pitted some 800 of Butler’s Rangers, Senecas and other Indians against about half that number of local militia. Near the settlement of Forty Fort the Loyalist forces lured the Patriots into an ambush, broke their line, and pursued and killed many of the militia, reportedly taking 227 scalps (a custom then practiced by Indians and whites on both sides). Iroquois warriors also killed a number of prisoners. Afterward, rumors of wholesale torture and murder by the Indians spread throughout the area, prompting thousands of settlers to flee. In New York state that spring and summer Brant led his Indians and Tories on raids of half a dozen settlements, burning them to the ground and driving off or killing their cattle, setting the stage for the most brutal of the actions, at Cherry Valley.

What happened at Cherry Valley that November 11 was indisputably a massacre, and Brant was to become one of the Patriots’ most reviled enemies. A complex man who straddled two cultures, he received a European education and associated with such luminaries as Aaron Burr, King George III, James Boswell and George Washington. Although known to his enemies as “the Monster Brant,” he often showed mercy and compassion in battle.

There is a strong argument that the depredations at Cherry Valley were instigated by Walter Butler, over the protestations of Brant. At the very least Butler lost control of his Indian warriors. That raid was undertaken in vengeance for the burning of several Iroquois settlements in October by a Continental rifle regiment and some Pennsylvania militia under orders from New York Governor George Clinton. Thus the raid on Cherry Valley was the most savage attack in a running series of mutually retaliatory border conflicts.

Washington was mindful that the key to overall victory lay in the East, but he could no longer ignore the British/Indian threat in the West. Though he was reluctant to divert any regular units, Washington realized that after the depredations in Wyoming and Cherry valleys, a significant military campaign was a necessity. The first choice to command such an expedition was Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, the reputed “Hero of Saratoga.” But Gates showed his characteristic reluctance to expose himself to combat and begged off on grounds of age and infirmity. Command of the expedition then settled upon Maj. Gen. John Sullivan, a truculent onetime New Hampshire lawyer whom Washington instructed in a detailed May 31, 1779, letter to move “against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents.” The immediate object of the campaign, Washington said, was “the total destruction and devastation of their settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible.” Sullivan was told to carry out his mission “in the most effectual manner, that the country may not be merely overrun, but destroyed.” The “total ruin” of the Indian settlements, Washington wrote, would guarantee America’s future security by inspiring the Indians with terror through “the severity of the chastisement they receive.” Washington added that should the Indians “show a disposition for peace, I would have you encourage it, on condition that they will give some decisive evidence of their sincerity by delivering up some of the principal instigators of their past hostilities”—namely Butler and Brant.

Sullivan was given four brigades—Brig. Gen. Enoch Poor’s New Hampshire and Massachusetts regiments, Brig. Gen. William Maxwell’s New Jersey Brigade, Brig. Gen. Edward Hand’s Pennsylvanians and Brig. Gen. James Clinton’s four New York regiments. These, along with additional rifle and artillery units, totaled nearly 4,000 men, or about one-fourth of the Continental Army at that time.

The mission was clear: Sullivan would lead three of the brigades out of Easton, Pa., up the Susquehanna Valley. Meanwhile, Clinton would take his 1,600 men west from Canajoharie, N.Y., and float or march down the Susquehanna from Lake Otsego to meet up with Sullivan’s force at Tioga, an Indian village at the junction of the Susquehanna and Chemung rivers. The Patriots would then march through Iroquois territory, destroying everything in their path and taking as many prisoners as they could manage.

Washington expected Sullivan to mount his expedition with all speed, but he was sorely disappointed. From June 18, when Sullivan’s brigade left Easton, to month’s end he’d progressed only as far as Wyoming, less than half the 145 miles to Tioga, much of it through trackless wilderness. And once camped there, no urging or goading from Washington, Continental Congress President John Jay or the Board of War could induce Sullivan to expedite his provisioning. Washington feared that word of the expedition would leak out, giving the Indians and their British allies time to mount a resistance. He needn’t have been concerned; the enemy had known of his plans almost from the first. But fortunately for the Continentals, the man in the best position to send enough reinforcements to stop the expedition—Sir Frederick Haldimand, British governor-general of Quebec—refused to credit the reports and did nothing.

The Indians did not have enough men to contest Sullivan’s advance. Butler was aware of both the size and significance of Sullivan’s army, but he was outnumbered.

By the time Sullivan finally decamped from Wyoming, he was so overprovisioned that, according to one officer, his men were “mired down with flour and baggage.” Sullivan’s ponderous expedition included 134 boatloads of supplies, 1,200 overburdened packhorses and some 700 head of cattle. Clinton apparently suffered from the same surfeit of supplies as his commander.

Sullivan’s six-mile-long caravan started lumbering up the Susquehanna Valley on July 31, its commander grumbling all the way about the poor support he’d been afforded by Congress. Upon reaching Tioga on August 11, Sullivan ordered Hand’s brigade to spearhead an attack on the nearby Indian town of Chemung. Scouts had reported a population of 200 to 300 Indians, but after a night’s march Hand’s force arrived at Chemung—only to find it deserted. This would become the norm. By then everyone from Pennsylvania to Canada knew Sullivan was on the march, so the Indians generally evacuated their towns before the Continentals arrived. Hand’s men looted and burned Chemung before walking into an enemy ambush just outside town. The Indians killed six soldiers and wounded nine or 10, sustaining an unknown number of casualties. Back in Tioga, Sullivan settled in to await the arrival of Clinton’s force, directing his men to build blockhouses and raise earthworks. His officers dubbed the works Fort Sullivan.

While Sullivan dawdled, another force of American soldiers and their Indian allies had joined the campaign. Washington had ordered Colonel Daniel Brodhead, based at Fort Pitt in western Pennsylvania, to move up the Allegheny River and destroy all Indian settlements he encountered. If feasible, he was to join up with Sullivan and Clinton and push toward the British stronghold at Fort Niagara. Washington hoped the capture of Niagara would shorten the war and boost the chances of an American victory. On the day Sullivan arrived in Tioga, Brodhead started upriver with some 600 soldiers, volunteers and militia and a contingent of friendly Delawares. Most of the villages Brodhead came upon were also deserted. He put all structures to the torch, as well as whatever corn, squash and bean stores his men could not pack as spoils. There must have been at least some Iroquois at home when Brodhead entered the villages, however, as part of the $30,000 in plunder he claimed at the end of his campaign was accounted for by the bounty in scalps.

Brodhead destroyed at least 10 villages, leaving behind only burnt stubble and charred timbers. The houses his soldiers torched were not the crude shelters or wigwams seen in fanciful period drawings; the Iroquois homes were log houses, framed structures and traditional longhouses. Though Brodhead’s force encountered minimal resistance, he never did link up with Sullivan’s force, claiming insufficient supplies. Instead, he turned back toward Fort Pitt. Regardless, Congress and the Patriots lauded Brodhead as a war hero.

August 11 was also the day when Clinton loaded his supplies onto 220 boats and embarked on his 160-mile journey downriver from Otsego Lake. He joined Sullivan at Tioga on August 22, and four days later the combined force moved out—more than two months behind schedule. The men methodically looted and destroyed every Iroquois town and village on their route into Finger Lakes country, their progress marked by smoldering villages and blackened fields.

On August 29 the Loyalists and their Iroquois allies tried to stop the Patriot juggernaut, at Newtown, near present-day Elmira, N.Y. Butler’s Rangers and their Indian allies had been sent from Fort Niagara to intercept the Rebels. Joined by Brant’s forces, their numbers totaled perhaps 1,200 men, confronting nearly 4,000 Patriots. The Tories tried to set up an ambush from a hillside redoubt, but Sullivan’s men flanked and routed them. Only 11 Patriots were killed, 32 wounded. The number of Indian and Ranger casualties is unknown but was significant. There would be no further organized resistance to the American expedition.

On September 15 Sullivan destroyed one last Iroquois settlement near present-day Geneseo, N.Y., and—considering his mission accomplished—turned for home. His army left a path of devastation that deserved the term “scorched earth.” Although it hadn’t carried the war to Niagara, as Washington had hoped, the Sullivan-Clinton Campaign had fulfilled both the letter and the spirit of its orders. “The army had brought a whirlwind of destruction,” according to historian Joseph R. Fischer. “Their torches had reduced 40 Iroquois towns and villages to ashes and destroyed 160,000 bushels of corn.” Sullivan reported to Washington and Congress there was “not a single village left in the country of the five nations.” By burning the Iroquois’ homes, crops and food stores, his army ensured the deaths of thousands by freezing and starvation during what would be the coldest winter on record at the time. Iroquois men, women and children went begging for shelter at British forts, only to find that their allies had little room and even less compassion for them. Washington did thus succeed in making the Iroquois a burden to and problem for the British. His plan for the destruction of the Iroquois homeland was a rousing success—almost.

Just a year later the Iroquois would have their revenge. At the end of the Sullivan-Clinton Campaign, Major Jeremiah Fogg, a member of the expedition, wrote, “The nests are destroyed, but the birds are still on the wing.” In the spring that followed that terrible winter, hundreds of warriors under Brant, Cornplanter and Butler—fired by a terrific lust for vengeance—descended on numerous towns along the frontier, including Cherry Valley, which they hit a second time. In these raids they destroyed an estimated 1,000 homes, 1,000 barns and 600,000 bushels of grain. Such attacks continued nearly to war’s end.

“The great, expensive expedition, glorious in its progress against the opponents of liberty, had in fact succeeded in leaving the people of New York more vulnerable, more isolated and less protected than before Sullivan’s army had marched,” according to historian Richard Berleth’s account in Bloody Mohawk. However, once the war had ended, the British were no longer in a position to supply their Indian allies. The 1783 Treaty of Paris finally ended the Iroquois threat to the States, and with the ceding of the greater part of Iroquois territory in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix the following year, the confederacy’s belief in itself as a separate entity was dispelled. Within decades the Iroquois’ homeland was transformed. Millions of acres were allocated for waterways, distributed to Patriot soldiers as payment, given and sold to settlers and land speculators. In a bitter twist of irony, four New York counties—established between 1794 and 1804—were dubbed Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga and Oneida.

On Oct. 26, 1825, New York Governor DeWitt Clinton, son of the general who had helped devastate the Iroquois, boarded the first barge celebrating the opening of the Erie Canal—which ran from Albany to Buffalo, bisecting the old Iroquois territory. The passage marked the opening of the West to commerce and settlement. The barge on which the governor traveled was named Seneca Chief.

For further reading, Ron Soodalter recommends Isabel Thompson Kelsey’s Joseph Brant, 1743–1807: Man of Two Worlds; Joseph R. Fischer’s A Well-Executed Failure: The Sullivan-Clinton Campaign Against the Iroquois, July–September 1779; and Richard Berleth’s Bloody Mohawk: The French and Indian War & American Revolution on New York’s Frontier.