In a Virginia mountain pass after Gettysburg, Meade had Lee’s army in the crosshairs, only to let him get away

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]en days after the Battle of Gettysburg, General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia found themselves trapped at Williamsport, Md., pinned between the rain-swollen Potomac River and elements of Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac. Lee actually had languished there for a week, saved perhaps only thanks to the tepid pursuit of Meade’s drained Federals, exhausted by their hard-fought victory at Gettysburg on July 1-3.

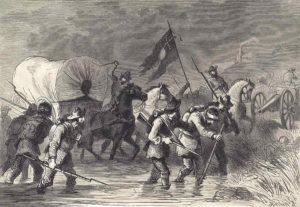

On July 14 Meade was finally ready to make a meaningful attack, after reconnoitering the Confederate positions for two days. But when the Federals moved on Lee at the appointed hour, they were dismayed to discover he and his army were gone. By fashioning bridges from barn material and fences, Confederate engineers provided the means for Lee to slip away, crossing the raging Potomac and into Virginia. A frustrated Meade wrote his wife Margaretta, “I start tomorrow to run another race with Lee.”

President Abraham Lincoln was beyond anguished at the news, declaring, “The fruit was so ripe, so ready for plucking that it was very hard to lose it.” Already pained at Meade’s slow pursuit of Lee, the president went on to express himself in terms so sharp that Meade asked to be relieved from command, a request quickly denied.

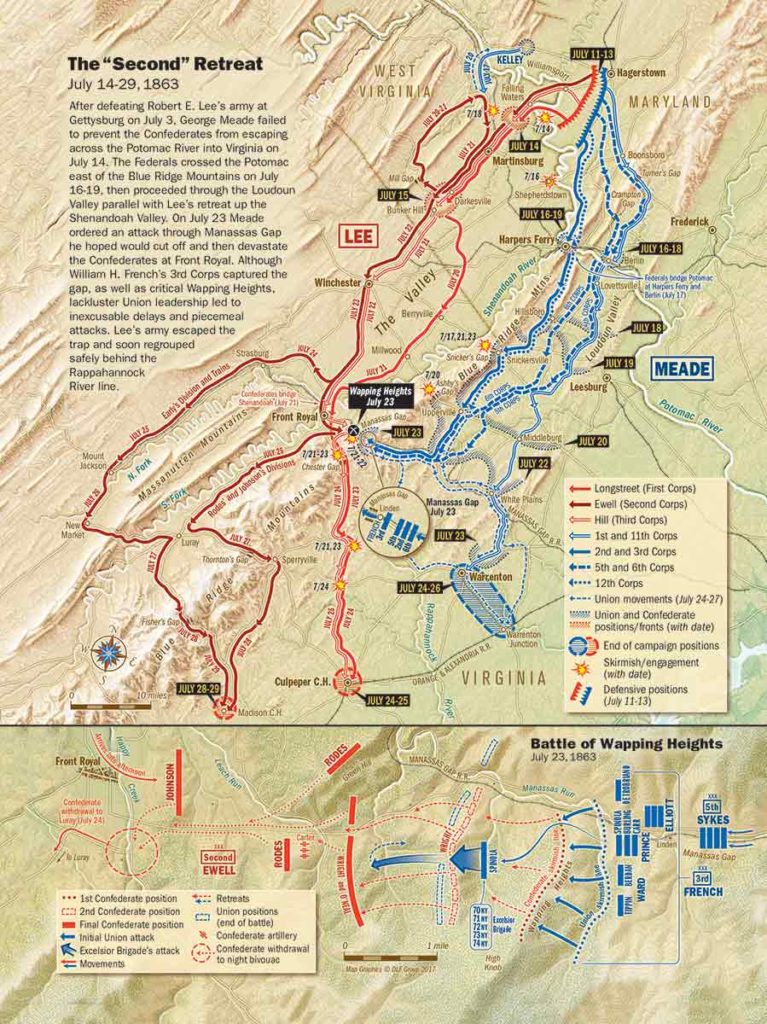

After crossing the Potomac, the Army of Northern Virginia proceeded to Winchester, west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Meade opted not to follow Lee directly but to move his army through the Loudoun Valley, east of the Blue Ridge. This, Meade reasoned, would allow for easier resupply by rail while keeping the pressure on the Confederate flank, forcing Lee to continue retreating south. If the opportunity presented itself, he could strike the Confederate flank through any of the ridge’s many passes and gaps.

It took the Federals three days to get across the Potomac, forgivable perhaps considering the troops had been marching nearly continuously since mid-June—stopping only to fight—and were thin on supplies, food, and endurance. To the men’s credit, their pace increased considerably once across the river, and by July 20 Meade had his men east of the Blue Ridge, parallel to Lee’s army as he intended. But both armies were dealing with brutal weather: stifling heat alternating with downpours.

Ahead of the main body, Federal cavalry scouted the key passes at Snickers and Ashby gaps while Lee deployed infantry and artillery to Manassas and Chester gaps, attempting to check Federal forces and prevent an attack on his retreating columns. As he approached Manassas Gap, near Front Royal, Meade learned that Confederates were directly opposite his position. It was the opportunity he’d been waiting for. If he threw a force through the gap and fell upon the center of Lee’s battered troops, he could potentially eviscerate the Army of Northern Virginia.

On July 21–22 Union cavalry units under Colonel William Gamble and Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt fought against a mixture of Rebel units over possession of Chester and Manassas gaps. Among the Confederates facing Merritt’s troopers for control of the easternmost part of Manassas Gap were Companies B (Warren Rifles) and C of the 17th Virginia Infantry; other elements of the 17th Virginia held the road to Front Royal at the western end of the gap. This was the first time troops raised in Warren County fought on their home soil, much to the delight of the local citizenry. “Huzzah! Bless our glorious 17th!” wrote Front Royal resident Lucy Buck. “How they have longed ever since the war [began] for a brush with the foe in the Valley and near their homes, and now that wish has been gratified, they’ve whipped them bravely and well and no doubt feel more exultant than they’ve ever felt after a miniature battle.” But the 17th would soon move west out of the gap and continue south with the rest of their corps, missing the larger battle to come.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]As Meade approached Manassas Gap, he learned that Confederates were directly opposite his position. It was the opportunity to eviscerate Lee’s battered army that he’d been waiting for.[/quote]

Meade issued orders to new 3rd Corps commander Maj. Gen. William H. French on July 22 to take Manassas Gap. Through the pass ran a railroad of the same name. This east-west line connected Manassas Junction to Front Royal and Strasburg. The plan was for the 3rd Corps to lead the attack followed by the 5th Corps, with the 2nd Corps held in reserve. To speed their movements, both attacking corps were ordered to leave their supply trains behind. Before midnight on the 22nd, all of the 3rd Corps was in position.

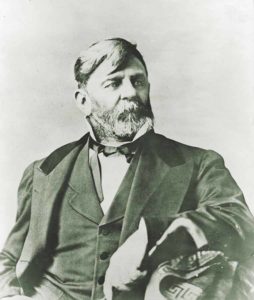

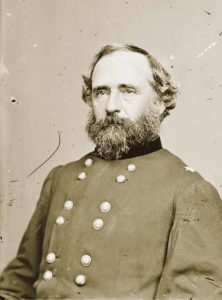

The corps had been wrecked during the three-day battle at Gettysburg, but was among the leading troops pursuing the Confederates. There had been some major command changes since Gettysburg. Major General Daniel Sickles was gone, his leg the victim of a cannonball during the July 2 fighting near the Trostle Farm, and he had been replaced by French. Earlier in the war, French had served as a brigade commander, then had a division within the 2nd Corps but had missed Gettysburg while garrisoning Harpers Ferry. It was these Harpers Ferry men who replenished the beat-up 3rd Corps. Brigadier General Henry Prince was the new commander of the corps’ 2nd Division and was among the oldest generals in the army. The 2nd Division, 2nd Brigade (known as the Excelsiors), on whom much of the upcoming fighting would depend, was also under new command. Brigadier General Francis B. Spinola, a 42-year-old New York politician who had previously led only Pennsylvania militia in minor coastal operations, was now heading perhaps the corps’ most seasoned brigade.

Fight Facts

Manassas Gap

(Wapping Heights)*

July 23, 18634

Campaign

Gettysburg (June–August 1863)

Commanders

Confederate:

General Robert E. Lee (Army)

Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson (Division)

Colonel E.J. Walker (Wright’s Brigade)

Union:

Maj. Gen. George G. Meade (Army)

Maj. Gen. William H. French (3rd Corps)

Estimaged Casualties:

Confederate: 170

Union: 130

Forces Engaged

Confederate: Army of Northern Virginia/Third Corps

Union: Army of the Potomac/3rd Corps

Outcome:

Inconclusive

*From staff reports/www.nps.gov/abpp/battles

Meade intended for his army to converge on Manassas Gap and push through to Front Royal, “cut[ting] off the tail of Lee’s retreating columns,” while Wright’s Brigade, Georgia troops now under the temporary command of Colonel E.J. Walker, had been assigned to guard the flank of A.P. Hill’s Corps as it passed through Front Royal. At daybreak on July 23, the brigade’s four regiments marched five miles east toward Manassas Gap. Alerted to the threat of three Union corps, the Georgians took up defensive positions on the gap’s adjacent hills and the railroad cut. Although the Yankees occupied the eastern part of the gap, the Rebels controlled the commanding high ground to the west.

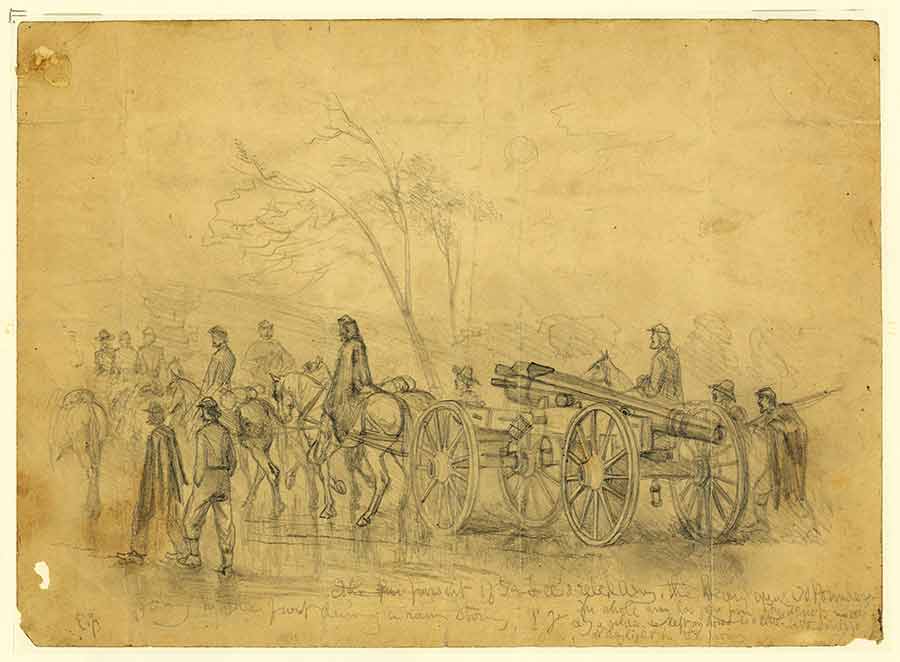

Early on the morning of the 23rd, French moved his 2nd and 3rd divisions forward, and by 9 a.m. they reached the entrance to the gap at Linden Station. A small battalion of skirmishers from the 1st Division was sent forward to “feel the enemy and to compel him to show his pickets on the heights as well as in the ravines.” They soon found the waiting Georgians on the high ground. This, French concluded, was “a large flank guard to delay our advance.” Beyond the gap could be seen “continuous columns of Lee’s cavalry, infantry, artillery and the baggage wagons moving all day from the direction of Winchester toward Strasburg, Luray and Front Royal.”

But exactly how large did a “large flank guard” need to be for a corps commander like French to modify his plans? Earlier reports of enemy movements perhaps led French to anticipate many more than just the four Georgian regiments detailed to face him. French obsessed all day about protection of his flanks and transmitted orders accordingly. Perhaps French did not fully divine Meade’s intentions and chose to fight with the objective only of seizing Manassas Gap and leaving destruction of Lee’s wagon train until the next day.

“About 11 a.m. the enemy appeared in the valley in our front in force—infantry, cavalry and artillery,” reported Captain C.H. Andrews of the 3rd Georgia. But for some reason French—“Old Blinky,” as he was known to his men—seemed in no great hurry this day. Another three hours passed before the 1st Division stepped off.

Andrews, meanwhile, sent urgent messages reporting his situation and requesting reinforcements. Second Corps commander Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell and one of his division commanders, Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes, appeared later on the field with promises of more Confederate troops. None of those arrived, however, before the Federals had swept the Georgians off the first and highest ridge, known as Wapping Heights. Wrote Andrews: “The enemy’s advance was very determined from the first, and after hard fighting, forced the left and center of our line to retire.” The 3rd Georgia, eventually isolated and unprotected on its right, reportedly did not retire “until flanked.”

By 4 p.m., Wapping Heights was in Union hands. Though Meade had been on the scene for some time, he apparently did little to spur French on when his troops stopped to consolidate their position overlooking a second ridge upon which the retreating Rebels had re-formed. Colonel Walker had been wounded during the fighting on the heights, and command of his unit devolved to a staff officer, Captain Victor Girardey, who conducted the movements on the brigade’s left while Andrews commanded the right. “Our line now extended about 2 miles, and was very weak, as our numbers were small,” wrote Andrews, who had about 600 muskets flank to flank.

Despite holding Wapping Heights, and with sunset expected around 7:30, French hesitated in pressing his attack against the still outmanned Georgians, preferring instead to bring up Prince’s 2nd Division. After an hour’s delay, the 2nd Division was in position, but many of their hungry and bored comrades in the 1st Division had begun to busy themselves during the delay by picking berries and chasing sheep.

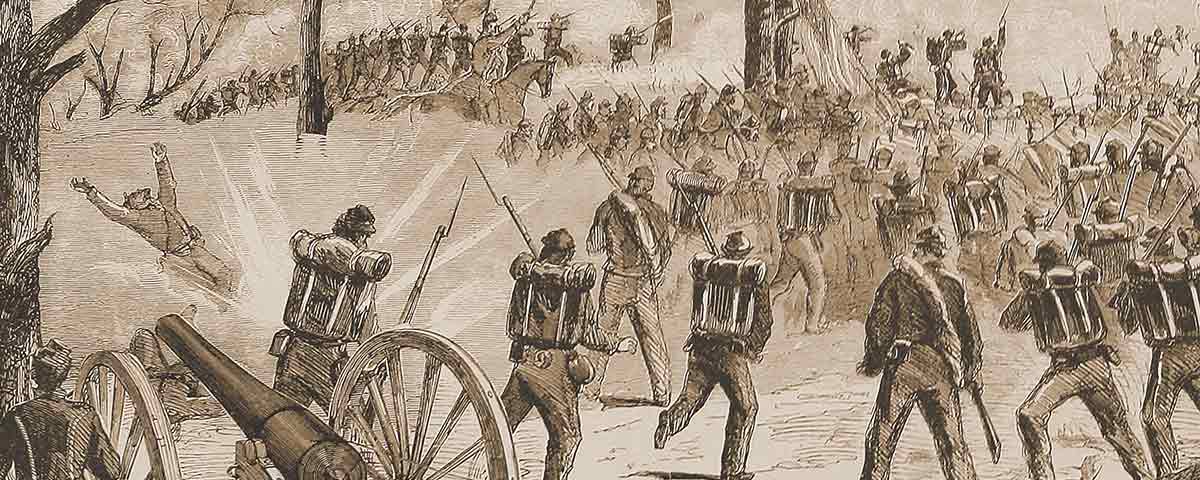

Around 5 p.m., Spinola was ordered to push his brigade forward (though absent the 120th New York and with fewer than 1,000 rifles). Moving past the men of the 1st Division and down the hill, the Excelsiors positioned themselves to lead the next attack. Halting at the base of the heights, the New Yorkers formed a line of battle as Spinola rode among the regiments shouting encouragement as well as orders to fix bayonets, a directive that energized the brigade. “We were put into line of battle and there told what we had to do. There were [sic] no use in telling us that for, we could see what we could do,” wrote Private James Dean of the 72nd New York. “The word was given to advance.”

Moving at the double quick, the brigade picked its way through a cornfield and some swampy ground, all the while under constant enemy musketry. Though slowed by a wide ditch and an enemy volley, the weight of the Federal numbers proved too much, and the Confederate line began to crumble. “With a yell that would have done credit to a band of demons, our boys sprang to their feet and rushed the foe,” read the 72nd New York’s after-action report. With regimental colors flying in the breeze, Spinola rode ahead of the men, his sword and pistol drawn, urging them forward with, “Now boys of the Excelsior Brigade, give them Hell.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”right”]French perhaps did not fully divine Meade’s intentions and fought with the objective only of seizing Manassas Gap, leaving destruction of Lee’s wagon train until the next day.[/quote]

The New Yorkers drove the Georgians before them, swarming over rifle pits as they collected prisoners. The Excelsiors made liberal use of the bayonet as fleeing Rebels discarded weapons, belts, and cartridge boxes. “I know that some of them was wounded with the bayonets of our men. I do not want to brag but I gave one of them an inch of steel myself,” wrote one New Yorker to his parents.

“We resisted them to the utmost of human capacity,” Andrews wrote, fighting “till our ammunition was exhausted, and, to enable us to fight at all, the ammunition was taken from the killed and wounded and distributed.” Outnumbered and in disarray, the Confederates retreated, scarcely able to fire a shot in return as the New Yorkers pursued, sometimes as close as 15 paces.

While chasing the fleeing Georgians, the Excelsiors came to another small hill, roughly 200 yards to the rear of the enemy’s original position. This hill had been reinforced by the men of Brig. Gen. Edward A. O’Neal’s Alabama Brigade, who suddenly rose, Prince would write, “as thick as men can stand, opening a furious fire of musketry.” This fire, along with shot and shell from a six-gun battery that had been brought up in support, rocked the New Yorkers. Spinola received two wounds and was forced to relinquish command to Colonel J. Egbert Farnum of the 70th New York.

Having charged more than three-quarters of a mile across rough ground and now facing a reinforced Confederate infantry line supported by artillery, with the sun setting, the bluecoats began to falter. Three attempts to carry the Rebel lines had failed, and with the brigade more and more disorganized a halt was ordered. According to the 72nd New York after-action report: “The first and second heights were carried in the face of a severe fire…the men, who were now completely exhausted, were ordered to hold the position.”

Under orders to consolidate his position, Farnum threw out strong pickets on both flanks while the remainder of the men built breastworks from stones and fence rails. The New Yorkers hunkered down behind the earthworks, occasionally trading shots with the enemy. “We were ordered to fall back to the top of a hill and laid there in line of battle while the rebels amused themselves by throwing shell at us for a time,” wrote Private Dean.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]“We resisted them to the utmost of human capacity…To enable us to fight at all, ammunition was taken from the killed and wounded and distributed.”-Captain C.H. Andrews, 3rd Georgia[/quote]

The famously tart-tongued Rodes had a somewhat different opinion of the New Yorkers’ attack. Union officers, he wrote, “acted generally with great gallantry, but the men behaved in a most cowardly manner. A few shots from [Lt. Col. Thomas H.] Carter’s Artillery and the skirmishers’ fire halted them, broke them, and put a stop to the engagement.”

With the Excelsior Brigade settled in on the forward line, Prince methodically brought up and positioned his 1st and 3rd brigades, all under the “leisurely” and somewhat ineffective fire of Rebel artillery. As the division made its final dispositions, preparing for a big push, darkness descended on the battlefield. Federal troops slept on their arms in line, scrounged for food as best they could, and prepared for next morning’s fight against what commanders expected to be an entrenched enemy.

But while Federals readied themselves, the Georgians—and indeed the whole of Rodes’ Division—made for the rear. “After dark, under orders from General Ewell, we commenced our march through Front Royal,” Andrews reported. After making their way across the Shenandoah River, Rodes’ men pulled up the pontoon bridges behind them before finally stopping two miles beyond Front Royal.

The Yankees awoke to find the enemy positions vacant, with only the dead holding vigil. Men in Prince’s division headed all the way to Front Royal only to find the discarded items of an army on the move. The Excelsiors eventually marched back to the battlefield and bivouacked for the night. The march south continued the next day.

What Federal commanders apparently believed was a strong line protecting the main Rebel force at Front Royal proved merely a rear guard tasked with delaying the Yankees for as long as possible, seldom stronger than an undersized brigade. All the while, the bulk of Lee’s army continued moving swiftly to the west. Had “Meade been one day earlier, or Ewell a day later,” Lucy Buck wrote, “our gallant Stonewall Corps would have been compelled to fight ten to one and defeated and cut off, our baggage trains lost, our pontoons captured…Thank heaven for so miraculous an escape.”

Meade’s opportunity to “cut off the tail” of Lee’s army and perhaps deliver him a fatal blow was gone. He had been hindered of course by the tentative performances of both Prince and French, but he had also been guilty of misreading the enemy’s intentions and had been unable to convey a strong enough sense of urgency of the situation to his subordinates. Whether or not French or Prince realized it, they had overwhelming numbers in their favor, yet French chose to engage his divisions only one at a time. And Prince, even with the entire 2nd Division at his disposal, allowed only one of his brigades to be engaged during the fighting.

While many of the men in the Excelsior Brigade took pride in their accomplishments that day, not all who witnessed the battle shared rosy assessments of their deeds and went so far as to label the engagement “Molasses Gap.” A soldier in the 5th Corps who watched events from a high knoll nearby wrote that his regiment had “the unique pleasure of watching the battle without being in it.…Aside from providing an entertaining spectacle, the 3rd Corps didn’t seem to be accomplishing anything.”

According to Rodes, who would be killed the following September at the Third Battle of Winchester: “The fight, if it be worthy by that name, took place in full view of the division and while the conduct of our men, and of Wright’s [Brigade] particularly, was the subject of admiration, that of the enemy was decidedly puerile.”

Reported losses for Manassas Gap, considered by some to have been the “last battle of the Gettysburg Campaign,” were about 170 killed, wounded, and missing among the Confederates (the bulk coming from Wright’s Brigade). Federal losses were roughly 130, with the vast majority suffered by the Excelsiors.

On July 24 Meade withdrew his men from Manassas Gap and, as portrayed in Harper’s Weekly, “marched leisurely on toward the Rappahannock.” He would have precious few chances to get the twist on Lee as nicely as the situation at Manassas Gap had offered. That November, Meade launched the entire Army of the Potomac into an unsuspecting and dispersed enemy near Mine Run, Va., only to have his plans unravel at the hands of French and his 3rd Corps subordinate Henry Prince. The following March the 3rd Corps was dissolved and its regiments reassigned throughout the army. That rid Meade of the ineffective French and Prince, both relegated to sit out the remainder of the war in backwater postings far away from the action.

Rick Barram, a history teacher in northern California, is the author of The 72nd New York Infantry in the Civil War. He thanks Matt Wendling of the Warren County (Va.) Planning Department for his help with this article.