On the afternoon of August 31, 1939, close to the Polish border in the German town of Gleiwitz, SS-Sturmbannführer Alfred Naujocks was waiting nervously in a hotel room with a team of seven SS men. They had arrived in town two days earlier and, posing as mining engineers, reconnoitered their target. Now they were waiting for the word to go. Their task was to stage an attack to give Hitler the excuse he wanted to declare war on Poland. They were starting World War II.

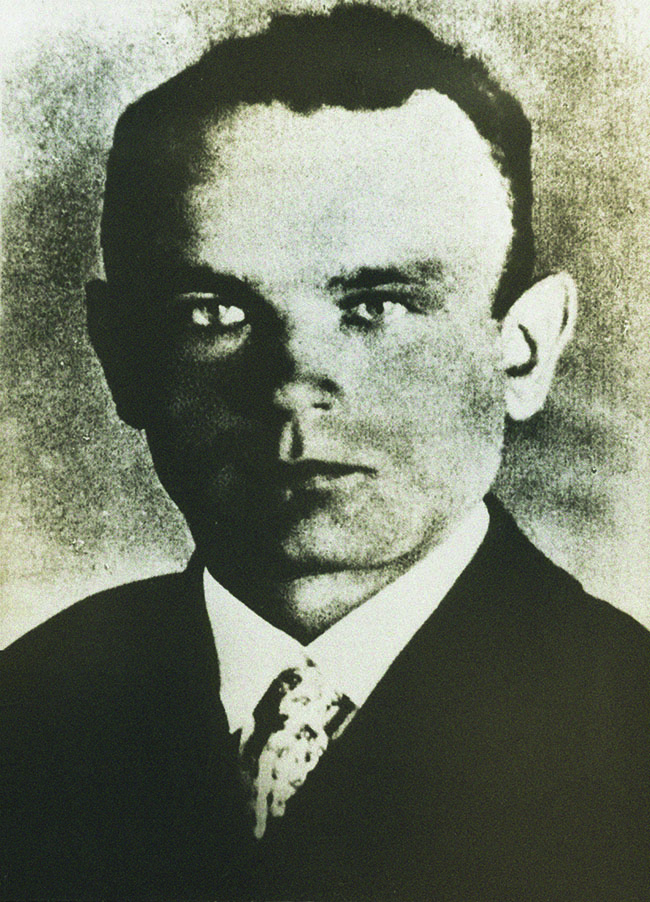

Naujocks, a 27-year-old from Kiel on Germany’s Baltic coast, had been an early convert to Nazism. Joining the SS in 1931, he had briefly attended university where he developed a talent for brawling and had his nose flattened by an iron bar–wielding Communist. Described by one contemporary as an “intellectual gangster,” Naujocks had risen swiftly within the SS hierarchy, falling under the patronage of Reinhard Heydrich, head of the German police network and SS security service, the Sicherheitsdienst, or SD. In that capacity, Naujocks assassinated a dissident Nazi in Prague in 1935 and helped establish a notorious high-class brothel in Berlin, Salon Kitty, patronized by visiting VIPs who could then be easily blackmailed; the rooms were bugged and the “madam” was an SS agent.

Having thoroughly proven himself to Heydrich, Naujocks was the SD leader’s agent of choice to run the mission in Gleiwitz. And it was Heydrich’s high-pitched, nasal voice down the telephone line from Berlin that gave him the code words to commence: “Grossmutter gestorben” (Grandmother has died). With that, Naujocks called his men together for a final briefing, reiterating their respective tasks and objectives. The mission was on.

TENSIONS BETWEEN Germany and Poland, which had rumbled on for some two decades, had spiked in the preceding few months. The ostensible reason for the friction was Germany’s territorial losses to Poland in the aftermath of World War I, as dictated by the Treaty of Versailles: primarily a swath of what had been eastern Germany on the Polish border, including parts of Upper Silesia and the provinces of West Prussia and Posen. Those losses, which amounted to over 25,000 square miles (about the size of West Virginia), not only contained upwards of five million people, including a sizable German minority, but cut the German territory of East Prussia off from the remainder of Germany by creating the so-called “Polish Corridor.”

Hitler’s ire—stoked by his racial prejudices and belief that Germany’s national destiny lay in expansion to the east—went deeper than losses of land, however. Growing more reckless in his saber-rattling, eager to capitalize on what he saw as Western weakness, and anxious for a war he thought would define him and his Third Reich, Hitler began to target Poland, ramping up the rhetoric and complaining continuously of Polish perfidy.

By the summer of 1939, even if the Poles had offered territorial concessions—they had not—it would not have been enough. Hitler wanted his war. But he faced a two-fold problem. For one thing, Poland had allies in the British and French, both of whom had pledged to stand by that nation in the face of foreign aggression. For another, although the vast majority of German people supported Hitler wholeheartedly, they had no stomach for another world war.

Hitler, therefore, had to dress up his belligerent intentions to appear defensive—to show Poland as the aggressor. In this way, he reasoned, the German people might be persuaded to support the war, and Poland might even lose its international allies’ support. Hitler summed up his attitude in a speech to his senior military commanders at his Alpine retreat above Berchtesgaden on August 22, 1939. “The destruction of Poland has priority,” he declared, adding, “I shall give a propagandist reason for starting the war, no matter whether it is plausible or not. The victor will not be asked afterward whether he told the truth.”

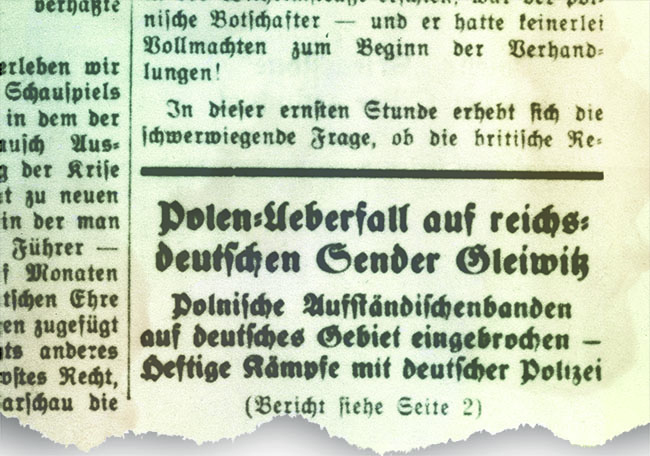

Throughout that summer, the world had seen much of Hitler’s propaganda offensive. While he railed publicly about Polish intransigence and the iniquities of Germany’s post-war territorial losses, his lieutenants quietly worked to drive relations to a breaking point and to cast Poland as the instigator. To that end, Heydrich removed all “politically unreliable elements” from the area along the Polish frontier. Within that zone, isolated properties, barns, and farmsteads were targeted in arson attacks to propagate the fiction in the German press that Polish insurgents were responsible. Through the summer of 1939, German newspapers carried countless lurid reports on what they called “Polish terror,” complaining of “Polish bandits,” “growing nervousness,” and the “frightful suffering” of the German minority. By the end of the summer, newspaper reports would claim that Poles had murdered some 66 Germans.

While the German media was busy slandering their eastern neighbors, the SS established a training center at Bernau, north of Berlin. There, more than 300 volunteers—mostly from the German province of Upper Silesia, a much-contested region on the Polish border that included Gleiwitz and that today is part of southwestern Poland and the Czech Republic—were preparing for infiltration and sabotage operations against Poland, training with Polish weapons and uniforms, and improving their grasp of the Polish language. By the end of August, those agents were ready for action.

They would be deployed on the night of August 31 in three staged raids, all in Upper Silesia. Aside from the attack at Gleiwitz, there would be a raid on an isolated hut for forestry workers and on a German customs post in the Hochlinden district, where, by smashing windows, firing into the air, and singing and swearing in broken Polish, the SS men were to simulate border incursions by Polish forces. Were it not for the bodies of six concentration camp inmates—given the contemptuous code name “Konserven” (canned goods), dressed in Polish uniforms, and then shot and left at the customs post to add authenticity to the scene—it almost would have been comical.

AMID THIS MURDEROUS PRETENSE, the action at Gleiwitz held special significance. By accident or design, it was only there that the attackers were required to give voice to their “mission” and broadcast their intentions to the world. To that end, Naujocks believed he had developed the perfect plan. From his earlier reconnaissance, he had identified the radio transmitter station at Gleiwitz, with its 380-foot wooden tower, as an ideal target. He reckoned that he and his men could easily take control of the site, lock up the station staff, fire a few shots into the ceiling, and broadcast an incendiary message in Polish over the airwaves before fleeing into the darkness. He had concluded that 8 p.m. would be the best time for the assault: dusk would provide cover, and most people would be at home then, listening to their radios.

Initially, Naujocks’s Gleiwitz plan was to proceed without bloodshed. But his superiors had decided that in order to make the propaganda all the more effective, the attack required a clinching piece of evidence. Heinrich Müller—head of the Gestapo—informed Naujocks that a Pole would be supplied, whose bloodied corpse was to be left at the radio station as irrefutable “proof” of Polish responsibility for the attack. For this reason, it was not enough to use one of the Konserven—the random concentration camp inmates used at Hochlinden; it had to be an ethnic Pole with a known history of anti-German agitation. That man was Franciszek Honiok.

Those who saw Honiok during the operation described him as almost entirely unremarkable. At five foot two, the 43-year-old farmer was shorter than average, and his dark blond hair was beginning to recede at the temples. But he was otherwise very ordinary—wearing a crumpled gray suit and possessing a slightly disheveled air.

Honiok had most likely been selected for his grim role from a file in Gestapo headquarters, far away on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse in Berlin. If anything, he was rather too well qualified. Born in Upper Silesia in 1896, he had fought on the Polish side during the Silesian Uprisings that followed World War I. After a brief spell living in Poland, he returned to Germany in 1925, where he was forced to fight deportation back to Poland—a case he successfully pursued all the way to the League of Nations in Geneva. Though his firebrand days may have been over by 1939, Honiok was still well known in his German home village of Hohenlieben—about 10 miles north of Gleiwitz—as a staunch advocate of the Polish cause.

As Gestapo captors hauled him away from there on the afternoon of August 30, 1939, Honiok had little idea of what was in store for him. They first drove him east to the police barracks in the ancient city of Beuthen, where he was given food and water, then to the Gestapo headquarters at the nearby city of Oppeln, where he spent an uncomfortable night locked in a file room. Throughout, his captors noted, he was “apathetic, his head constantly bowed.” He never spoke, and no one spoke to him except for a few words of instruction from his Gestapo escort. Moreover, despite the German mania for paperwork, he was not registered in any of the locations through which he passed; it seemed they wanted him to remain untraceable. The following morning, August 31, his captors took him to the police station at Gleiwitz and placed him in solitary confinement—again with no records filed. It would be the last day of his life.

ACROSS TOWN THAT EVENING, Alfred Naujocks and his men, outfitted in civilian clothes to resemble Polish insurgents, climbed into two cars for the short journey northeast to the transmitter station. Arriving precisely at 8 p.m. as planned, and with dusk rapidly falling, they rushed into the building. Pushing past the station manager, who rose to meet them, the SS agents overpowered the staff and took them down to the basement, where they were ordered to face the wall and had their hands tied behind their backs. Meanwhile, Naujocks and a radio technician on his team tried to work out how to make their incendiary broadcast.

One of the problems that Naujocks had needed to solve in his planning was how to ensure the proclamation would be heard. He had considered targeting the main radio station in Gleiwitz—a much larger facility where the studios were located, closer to the city center—but had decided against it. The larger station would have presented an increased logistical challenge, and there was the likelihood that the transmitter station would monitor its broadcasts and cut them off. So he decided instead to hit the transmitter station itself, which greatly reduced the possibility of the broadcast being silenced.

However, the transmitter station had only a “storm microphone,” used to interrupt local programming to warn of extreme weather. Naujocks’s technician found the microphone in a cupboard but was unable to connect it, so Naujocks hauled the station’s staff from the basement at gunpoint, one by one, until one of them—a technician named Nawroth—successfully connected the device. With that, the group’s only fluent Polish speaker, Karl Hornack, pulled a crumpled sheet of paper from his pocket and stepped forward. As someone fired a pistol into the air to provide an appropriately martial atmosphere, he read:

“UWAGA! TU GLIWICE! ROZGŁOŚNIA ZNADUJE SIĘ W POLSKICH RĘKACH!”

(“Attention! This is Gleiwitz! The radio station is in Polish hands!”)

What followed was supposed to be a call to arms from the fictional “Polish Freedom Committee,” demanding that the Polish population in Germany rise up to resist German authorities and conduct sabotage operations, promising that the Polish army would soon march in as a liberator. But for reasons that have never been satisfactorily explained, only the first nine words were broadcast—and those only to the district of Gleiwitz itself. The remainder was lost in a cacophony of static. Heydrich, listening eagerly in Berlin, heard nothing at all.

While Naujocks was busying himself with the broadcast, SS handlers delivered an unconscious Franciszek Honiok to the building. Shortly before 8 p.m., an SS man in a white coat, purporting to be a doctor, had visited Honiok in his cell at the Gleiwitz police station and given him an injection. Honiok was then driven the short distance to the transmitter station, where two of Naujocks’s men carried him into the building and laid him down near the back door. At some point—it’s not clear when—someone shot him. As Naujocks left the radio station, he stopped briefly to examine the now-dead Honiok, his face smeared with his own blood. Naujocks would later maintain that neither he nor his men had shot him. He knew nothing about the man, he would tell prosecutors, not even his name: “I was not responsible for him,” he said.

Franciszek Honiok was expendable. He was simply a corpse—a bloodied, silent witness to be paraded before the German and international press as proof of “Polish aggression.” His murder demonstrated in full measure the sneering, contemptuous brutality of the Nazi regime, and was a grim foretaste of the fate that would befall Poland. But its significance was even more profound than that. It was a single death that prefaced at least 50 million others: an individual tragedy presaging a collective slaughter.

It did not matter that the ruse to which Honiok’s body had given spurious credence—Naujocks’s radio broadcast—had failed; the German media were already primed and ready to run the story regardless. Within hours, radios were blaring and newspaper presses rolling, churning out headlines about the Polish “attack” and the inevitability of German “retaliation.” By the time most Germans read those words the following morning, Hitler’s tanks were already advancing into Poland. World War II had begun.

BUT WHAT OF ALFRED NAUJOCKS? How did his war pan out? At first glance, he went on to an impressive wartime career. As Heydrich’s cat’s paw, Naujocks appeared to have led a James Bond-like existence, participating in and leading some effective clandestine operations. He masterminded the kidnapping of two British secret agents in neutral Holland in November 1939—the so-called “Venlo Incident”—which compromised the entire Western European network of Britain’s MI6 secret intelligence service. He also headed a brutal suppression of the Danish Resistance in 1943, and was one of the brains behind Operation Bernhard, an ingenious German plan to forge huge numbers of Sterling bank notes, which were to be dropped over the UK to collapse the British economy. Though Naujocks did not see the project through to its fruition, and the air-drop was never carried out, the operation produced some £150 million in counterfeit notes ($195,525,000 at the time, or nearly $3 billion today)—some of the best forgeries that the Bank of England had ever seen.

Yet Naujocks’s stellar career was not all it may have seemed. Life as Heydrich’s chosen one was evidently not a bed of roses. His master was demanding and vindictive, and—presumably due to the weight of compromising knowledge—did not permit his agents to leave his employ easily. Naujocks would later claim that his relationship with Heydrich was a highly toxic one, marked by a series of acrimonious clashes. Naujocks balked at some of the more extreme assignments and claimed to have refused to carry out a high-profile assassination. As a result, Heydrich branded him a coward and reprimanded him. Yet when Naujocks resolved to leave the SD in 1940, Heydrich vetoed five requests for transfer. In 1941, Naujocks was charged with corruption, stripped of his rank, and sent to the Eastern Front as a simple soldier in the ranks of the Waffen-SS. He had little doubt Heydrich was trying to have him killed.

After Heydrich’s assassination in Prague by British-trained Czechoslovakian agents in June 1942, Naujocks claimed that for the first time in the war he was able to “breathe again.” He took a desk job in the German administration in Brussels, in occupied Belgium, and settled into a comfortable routine, enjoying the perks of a German officer. Thanks no doubt to his reputation, former SD associates continued to approach him with secret missions, but he usually demurred, claiming ill-health and citing the shrapnel injuries he had incurred on the Eastern Front.

Then, in the autumn of 1944, Naujocks defected. Surrendering to approaching American troops in Belgium, on the frontline near the German border, he told them his name was Alfred Bonsen and asked to be taken to a commanding officer. In his kit bag, he had a change of clothes, a large sum of money in three currencies, and a letter addressed to an official in the Foreign Office in London. When he confessed his true identity, the Americans handed him over to the British, who transferred him to the infamous “London Cage,” a facility in Kensington for the interrogation of high-profile prisoners.

The British were condemning of Naujocks. Though his interrogators conceded that he was a “goldmine of information,” praised his “truthfulness and frankness,” and noted admiringly that he never asked to cut a deal, they were nonetheless damning in their assessment of him. He was, they said, an “effeminate sadist,” a “killer without shame,” and a “callous murderer” who was “capable of any underhand activity,” a man who “would sell his own mother.” At best, they summarized, he was a coward; at worst, he was engaged in “another diabolical plot.” The report concluded starkly that, “this man should most certainly be put to death.”

And, when the British had finished milking Naujocks for information, that was what they had in mind for him. On August 31, 1945—six years to the day after the Gleiwitz operation, and nearly four months after the war ended—they transferred Naujocks to the American occupation zone in Germany, where he would again be interrogated, his affidavits transcribed for later use in the Nuremberg trials. Naujocks did not take the stand at Nuremberg, however; instead the Americans handed him over to Denmark, which tried him for war crimes alongside numerous former heads of the SS and Gestapo. Sentenced to 15 years in 1949, he served barely a year in a Danish jail before he was deported back to Germany. There he disappeared into postwar obscurity, living in Hamburg under a false name.

By that time, Naujocks was scarcely remembered. Like Franciszek Honiok, he had become a footnote to the wider history of World War II. When he died in 1966 at age 54, all he left behind was a breathless 1960 biography by an Austrian journalist and historian, Günter Peis, whom Naujocks had met at the Nuremberg trials. Naujocks wrote the foreword. It begins: “I am the man who started the war.” ✯

this article first appeared in world war II magazine

Facebook @WorldWarIIMag | Twitter @WWIIMag