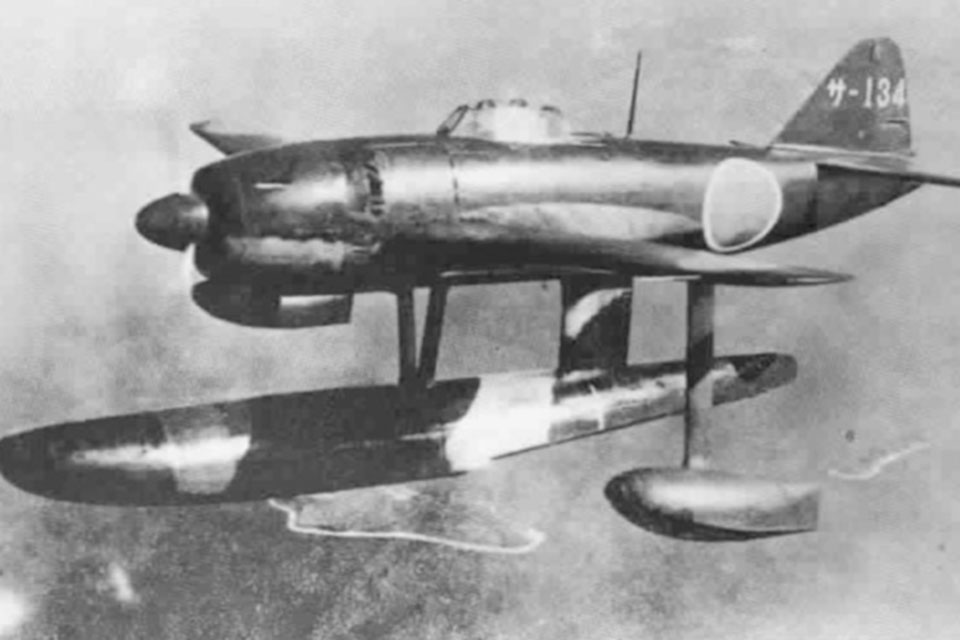

You’ll have to visit Texas to see the only restored Kawanishi N1K1 floatplane currently on display.

The center of Texas’ Hill Country seems like an unlikely place to find one of the rarest World War II aircraft, a Kawanishi N1K1 Kyofu. Only 89 of the Japanese floatplane fighters, code-named “Rex” by the Allies, were produced from May 1942 until March 1944. Two other airframes are known to still exist, but the aircraft at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg is the only example that has been restored and is on public exhibition.

The Rex arrived in Fredericksburg on February 12, 1976, according to Mike Lebens, curator of the museum’s collections, who also noted that documents indicate it was initially there on loan from the National Air and Space Museum. Ownership would eventually be transferred to the National Museum of Naval Aviation in Pensacola, Fla.

The Rex’s cockpit was incomplete, but the rest of the plane was in good condition. It had been painted and preserved to some extent. Shortly after it arrived, the N1K1 was put on display at what was then Fredericksburg’s Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz Naval Museum (Fredericksburg was the boyhood home of Nimitz, WWII commander in chief of Allied forces in the Pacific).

The floatplane was placed in storage in the early 1990s. It could still be viewed by visitors, but only on a limited basis.

Early in 2009, the museum asked the Naval Aviation Museum for permission to refurbish, clean and repaint the aircraft. A “cosmetic restoration” was approved, and work started that spring. While the work was ongoing, the state-sponsored museum underwent a 40,000-square-foot expansion.

Kawanishi developed the N1K1 in response to an anticipated need by the Imperial Japanese Navy for a float-equipped interceptor like the Nakajima A6M2-N (dubbed “Rufe” by the Allies). In September 1940, engineering work started on what was to become the N1K1 Kyofu. The early design featured a single-seat, all-metal monoplane with a central float and two inflatable stabilizing floats on the wingtips. Eventually the inflatable floats were determined to be too heavy and complex, so they were replaced by a pair of smaller fixed wingtip floats.

The floatplane was initially powered by a 1,460-hp Mitsubishi MK4D Kasei, a 14-cylinder, air-cooled radial that turned a pair of two-bladed contrarotating propellers. The contrarotating props were an attempt to alleviate takeoff problems created by the engine’s torque, but the complex gearbox they required turned out to be a constant source of trouble. As a result, the MK4D was dropped in favor of a new MK4C Kasei 13 radial engine that drove a single three-bladed prop.

The N1K1 made its maiden flight on May 6, 1942, instantly becoming a hit with Imperial Japanese Navy pilots—though some expressed concern over difficult takeoff characteristics. Once in the air, the aircraft handled well due to large Fowler-type combat maneuvering flaps. The floatplane was expected to support forward troop operations where there were no airstrips or aircraft carriers.

The N1K1 finally entered service in July 1943, but the delivery rate was very slow; after six months the Japanese navy had received only 15 of the floatplane fighters. By then the war had shifted in the Allies’ favor, and the N1K1 was relegated to an interceptor base in Borneo. Even with dual 7.7mm machine guns in the cowling and wing-mounted 20mm cannons, the Rex was no match for the Americans’ F6F Hellcats and F4U Corsairs, a factor that played in the decision to terminate production after only 89 aircraft were built.

Kawanishi considered the design—minus floats—an able interceptor, going on to produce the N1K1-J Shiden and improved N1K2-J Shiden-Kai, code-named“George”by the Allies. Land-based Japanese pilots would come to regard the Shiden-Kai as one of the best fighters in their arsenal.

The job of refurbishing the Texas Rex was tackled by Ken Fisher, a museum volunteer, military historian and modeler, along with his two sons and a group of volunteers. By the time they started, the aircraft had been stored in a pole barn for about two decades. Fisher recalled it was in “pretty good condition with very little surface corrosion.” The project began in January 2009, with disassembly work starting a month later. There was a strict deadline: The team had six months to finish, before a section of wall went up in a gallery where the N1K1 would be exhibited.

Fisher recalled the biggest problem was getting the airframe into manageable pieces. Handling the heavy lifting was the rigging firm C. Young and Company Inc., from Austin, which employed specially outfitted forklifts and yards of nylon strapping to remove and lift off the empennage, separate the fuselage from the huge main float, lift the engine from its mounts, and finally remove and separate the wings. The disassembly was done without the aid of manufacturer’s blueprints, Fisher noted.

Before the plane was disassembled inside the pole barn, custom cradles had been built to hold the wing sections, engine, floats and tail section. With the aircraft in pieces, the airframe could be inspected and any corroded metal could be replaced.

“We did [paint removal] the old fashioned way, with chemical strippers,” Fisher explained. As the old paint was washed away, he discovered that the airframe had been initially sprayed with a “red lead-type primer.”A similar primer was reapplied to keep the Rex as historically correct as possible. Fisher also found that part of the aircraft was in good enough condition to facilitate color matching. Those sections’ colors were computer-matched, to ensure that authentic hues could be used later in the project.

Noting he found some corrosion on the spar caps of the horizontal stabilizer, Fisher said, “If the airplane was ever to fly again, it would have to have a complete disassembly and be checked thoroughly for any type of damage.” But as this was a cosmetic restoration for display purposes only, no structural work was necessary.

Fisher said he was very impressed with the overall construction, but noted that some modifications had evidently been made to the underside of the wings toward the end of the plane’s service life. He described the somewhat crude work done to add bomb shackles as “very bad.”

Museum contractors left a section of the new wall open for the riggers to slip the refurbished fuselage inside its new home. After that the wings were attached and the engine was bolted into place. “It was a tight fit,” Fisher recalled. They had only inches to spare once the aircraft was placed on its main float and beaching dolly.

As no precise color scheme records were available, Fisher consulted several profile publications and scale model kit manufacturers for guidance. His research led him to paint the N1K1’s underside a scale model color carefully matched to reproduce WWII Imperial Japanese Navy gray, while the upper surfaces were sprayed with a duplicate shade of IJN green. Fuselage sections where original stencils were still readable were masked off and left intact. Once the painting and major assembly work were complete, Fisher spent the next few months replacing fairings and other small details to finish the project.

The N1K1 Rex is now one of the centerpieces of the museum’s new gallery. The gallery also houses a rare Aichi D3A2 “Val” dive bomber, similar to those that took part in the Pearl Harbor attack. For more info, visit pacificwarmuseum.org.

Originally published in the May 2012 issue of Aviation History Magazine. To subscribe, click here.