[dropcap]A[/dropcap]t 11:45 p.m. on October 15, 1946, Allied guards were preparing to escort top Nazis convicted of war crimes from their cells in Nuremberg to the prison gymnasium for hanging. The condemned included Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s foreign minister, and General Alfred Jodl, chief of the German General Staff. The best known was Hitler’s deputy, the Wehrmacht’s highest-ranking officer, one of Europe’s richest and most powerful businessman, and head of the Luftwaffe: Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring.

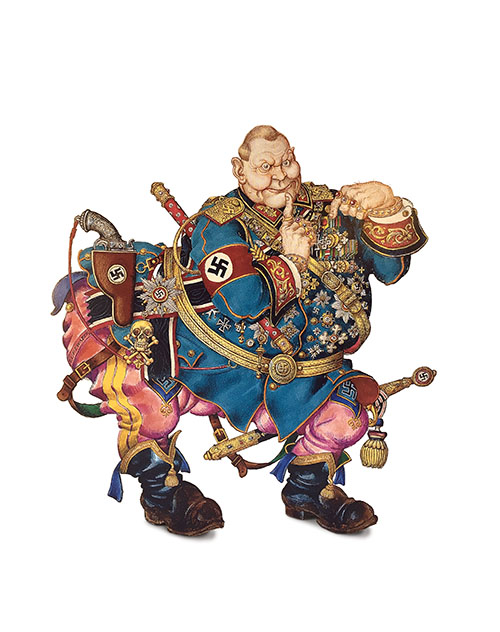

Göring had fallen far. In early May 1940, he commanded the world’s most powerful air force, poised to roar from continental victories and triumph over hated England. At home, Germans adored their Führer, but found in der dicke Hermann—“Fat Herman”—a figure of ebullient entertainment. Slender, ascetic Hitler ate only vegetables, abstained from smoking and drinking, and wore mainly plain gray jackets. Not Göring. In flamboyant uniforms of his own design and fingers bedizened with rings, the fat man ate, drank, and made riotously merry, living out loud.

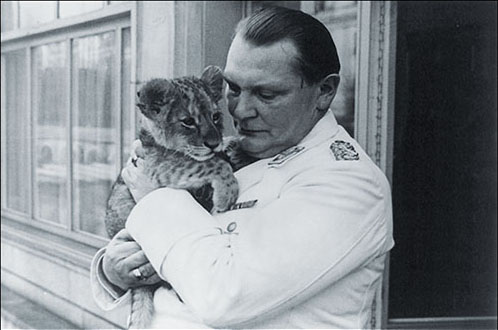

Florid style suffused Göring’s life. He loved food, wine, art collecting, and hunting. His country lodge, Carinhall, named after his beloved first wife, abounded with sculptures, paintings, and furniture. Endangered species roamed his grounds. He kept pet lions. He adored cars and sailing; he called his 90-foot motor yacht Carin II.

Göring’s dandy image made him a persistent figure of ridicule. Germans mocked him and the foreign press painted him as an overweight buffoon. But Hermann Göring was a colossus in every way: a wily Machiavellian with an outsize IQ, skilled at combining charm, guile, and ruthlessness to get what he wanted—skills he employed to the end.

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]ermann Wilhelm Göring’s name had been a household word in Germany since his early 20s. After spending 1914-15 in the trenches of the Western Front, he finagled his way into the air service, flying on the sly as an unofficial observer for a friend. Found out, he formally transferred to the service, becoming a fighter pilot—a good one. His 22 victories earned him the Orden Pour le Mérite—the Blue Max, then Germany’s most exalted combat award. In July 1918, Göring, 25, assumed command of the famed “Flying Circus,” Jagdgeschwader 1, led by Manfred von Richtofen until the Red Baron’s death in action three months earlier.

After the Armistice in November 1918, Göring gravitated to barnstorming, performing aerobatic displays and demonstrations in Scandinavia for the Fokker Company. In autumn 1919 he was flying passenger planes for airline Svenska Lufttrafik. A war hero and decorated ace, with pale blue eyes and lean, dashing good looks, Captain Göring made a splash in Swedish society.

One night in February 1920, he flew Count Eric von Rosen, a wealthy explorer and right-winger, to Rosen’s lakeside castle at Rockelstad. Göring pressed through several blizzards executing a perfect landing on the frozen lake. Rosen invited the pilot to stay; other guests included Rosen’s sister-in-law, Carin von Kantzow. Göring fell hard for the similarly smitten—and married—Carin, then separated from her husband; their affair generated gossip across Stockholm that propelled the couple to Bavaria.

They were staying in the mountains near Munich in late 1922 when Göring, who was trying to organize former military men into a political party, attended a rally in Munich protesting the Versailles Treaty. As the crowd shouted for a “Herr Hitler” of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party to speak, Göring realized the fellow was standing only yards from him. Hitler kept silent, but something about the man impelled Göring to attend the next session of the salon the Austrian held Monday nights at Café Neumann.

That evening, Hitler spoke vividly of resisting the Versailles Treaty with bayonets—just the kind of fiery rhetoric Göring yearned to hear. The pilot stood and spoke of the need to put honor first in any conflict. Chatting afterward, he and Hitler felt a mutual man-crush; Göring drawn to Hitler’s pugnacity, Hitler to Göring’s glamour and connections. Göring joined the fledgling party the next day.

By January 1923, Hitler had put his new associate in charge of the Sturmabteilung, known as the SA, the organization’s paramilitary wing—then a motley rabble. Göring quickly whipped the SA into shape, recruiting and arming more men while imposing structure and discipline. The next month Göring and Carin married; by summer he had quit flying to support Hitler—organizationally and financially—run the SA, and look after his bride. He was becoming a politician.

That November, Hitler persuaded war hero General Erich Ludendorff to head a coup to take over Munich. At a speech by the Bavarian State Commissioner, Hitler, guarded by SA toughs, leaped to the stage declaring a revolution. The Beer Hall Putsch collapsed but not before Hitler, Göring, and about 3,000 fellow Nazis marched into Munich’s heart. Police opened fire, killing 16 and wounding Hitler and others, including Göring, who was shot in the groin.

Göring reluctantly relinquished leadership of the SA to Ernst Röhm, a brutal war veteran, while he recovered during a long, forced exile in Italy and Austria. To ease Göring’s persistent pain, doctors injected morphine; he became addicted to the opiate. His dependency became a lifelong plague causing or exaggerating many of his outlandish characteristics. The drug induced a sine wave of effects, from energetic euphoria to morose passivity, as well as weight gain, vanity and delusions, and extreme anxiety.

The imprisoned Hitler asked Göring to seek financial backing from Benito Mussolini and his Fascists, an odyssey that ended in humiliation. He and Carin, now broke—in part from loaning the Nazi Party money—resented the charity they needed. Irritation fed their growing anti-Semitism and devotion to the National Socialist cause. “Never in this life was it so hard to exist, in spite of all the happiness I have with my darling Hermann,” Carin wrote in late 1924.

Addiction drove Göring into an asylum in 1925 and again briefly in 1927. He emerged from these dark passages by force of will and with his wife’s encouragement, only to find out the Nazis dumped him from the roster. Carin’s health waned, compromised by tuberculosis; by early 1927, at age 38, she was in a Swiss nursing home. Göring was in Germany seeking work, trying to rekindle his political career and quit dope. “Darling, darling, I think of you all the time,” Carin wrote to him. “You are all I have, and I beg you, make a really mighty effort to liberate yourself before it is too late.”

[dropcap]G[/dropcap]öring pulled himself from the precipice. In the upcoming 1928 spring elections, he wanted to run for the Reichstag; Hitler said no. Knowing that the Nazis once had the secret backing of industrialists, Göring told Hitler that unless he got his endorsement he would make the information public and sue Hitler’s underwriters for every pfennig he and Carin had loaned the party since 1922. Hitler folded, and in May, Göring won the election as one of 12 Nazi deputies, entitled to a salary, influence, and, above all, opportunity that he was determined not to waste.

On June 13, 1928, Carin was strong enough to accompany him to the Reichstag opening in Berlin. His party’s marginality didn’t bother him. “We were the Twelve Black Sheep,” he said. Göring had found his métier. While Carin played hostess, he set to work with the energy of a thunderbolt. He declared himself the party’s transportation expert, nurturing contacts in the aviation and auto industries. Hitler asked him to woo Berlin society to the Nazi cause. A natural firebrand, Göring quickly learned to play to an audience. He was now Hitler’s most valuable asset. At the next election, in September 1930, the Nazis won 107 seats, making them the Reichstag’s second biggest faction. The party needed a deputy speaker; Hitler appointed Göring.

As the new deputy speaker, Göring traveled on behalf of the Party, orating with rabble-rousing style. In July 1931, he addressed 30,000 struggling farmers ripe for recruitment. “He was so moved to see all these people in need,” wrote Carin. “There they all stood, singing ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über Alles,’ most of them with tears streaming down their faces. How his nerves stand it beats me.”

Carin’s health, however, continued to fail. A heart attack laid her low just one day after her mother’s funeral in September 1931. She died the next month in a Swedish sanatorium with Göring at her side. Grief and remorse hammered at him. His marriage had dragged him from his morphine addiction and empowered him to succeed. “And that,” he told Carin’s niece, “was how my megalomania began.”

[dropcap]G[/dropcap]öring overcame sadness through work. In the July 1932 elections, the National Socialists won with the largest percentage of the vote. President Paul von Hindenburg refused Hitler the chancellorship, but Göring became president of the Reichstag. In January 1933, when Hitler did become Chancellor—largely thanks to Göring’s negotiating skills, nerve, and ruthlessness—Göring became the Führer’s right-hand man.

During the first year of Nazi rule, Göring purged Communists, Jews, and dissidents and paved the way for a one-party state using manipulation, bribery, and hired thugs. He was now Reich Commissar for Aviation and head of Germany’s largest police force. He bound the nation’s industries to the Nazis through coercion. “I’ve always said that when it comes to the crunch he’s a man of steel—unscrupulous,” Hitler later said.

In April, Göring set up the Forschungsamt, his personal spy agency, with Hitler’s consent. The operation bugged and tapped the phones of foreign leaders and businessmen, and almost every Nazi leader. In the regime’s power struggles, Göring always stayed a move ahead.

Publicly, he created the Geheime Staatspolizei, the dreaded Gestapo secret police. He set up the first concentration camps—originally holding pens for Nazi Party foes— at Oranienburg and Papenburg in the German state of Prussia. Titles attached themselves to him: Speaker of the German Parliament, President of the Reichstag, Prime Minister of Prussia, President of the Prussian State Council, Reich Master of Forestry and Game (his hunting laws still exist), and commander of a clandestine air force.

With the Nazis in power, the SA and its storm troopers lost their utility, making their ambitious leader, Röhm, a threat to Hitler. Göring urged Hitler to destroy Röhm and his top goons, a step he got SS chief Heinrich Himmler to endorse. In return, Göring handed off the Gestapo to the SS, which took over as the party’s military wing.

The resulting June 30, 1934, bloodbath, known as the Night of the Long Knives, was almost entirely a Göring production. He kept to his Berlin villa, sitting at a large oak table on a gold-trimmed velvet chair, while hit squads and SS men assassinated Röhm and at least 83 others. A few days later, Göring organized a crab feast for fellow “managers” Himmler and Erhard Milch, Göring’s number-two in the air force. While they cracked open claws, a telegram from President Hindenburg arrived applauding their “energetic and victorious action.”

That August, Hindenburg died and Hitler became Führer of the Third Reich. The Luftwaffe came out of the shadows, with Göring as commander-in-chief. Hitler often used him as his unofficial deputy—over deputy Rudolf Hess—and eventually elevated Göring to the rank of Reichmarshall, the only German officer ever appointed to the position. The grand elevations hugely increased Göring’s power. But they also short-changed him of the practical experiences of an officer rising through the ranks—a bill that would come infamously due.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]mong the Führer’s henchmen, Göring was the one most at ease with the Volk, a gregarious and optimistic contrast compared to dour mopes like propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels. Amid countless jokes at his expense, he outranked any Nazi in popularity except Hitler. Göring’s annual winter ball was the social event of the year, and his uniforms and pomp grew ever more outrageous.

Agriculture minister Walter Darré once visited Göring as the Reichsmarschall’s valet was dressing him. A second servant presented a cushion on which lay 12 rings—four each of red, blue, and green. “Today, I am displeased,” Göring told Darré with no small amount of campiness. “So we shall wear a deeper hue. But we also desire to show that we are not beyond hope. So we shall wear the green.” On another occasion, a woman invited to tea found the Luftwaffe commander wearing a toga, jewel-encrusted sandals, and rouged lips.

The big man missed being married, and went looking for another wife. His eccentricities did not put off former actress Emmy Sonnemann, who in April 1935 became the second Frau Göring. For their Berlin wedding, 30,000 soldiers lined the streets. Wrote a foreign reporter: “You had the feeling that an emperor was marrying.”

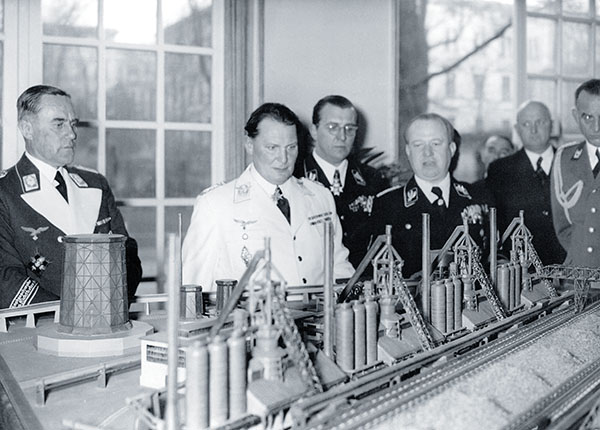

In April 1936, Hitler assigned Göring control of oil and synthetic rubber production, critical in a belligerent country short on petroleum. That summer, Göring was a dynamo, quickly absorbing economic principles and introducing tax breaks and other innovations. He bartered with Yugoslavia, Romania, Turkey, and Spain for foodstuffs and raw materials, while investing at home in research into synthetic fuels and other emerging technologies. Göring recruited Germany’s best economists and leading industrialists to his new cause.

That October, Hitler adopted his proposals, naming Göring Special Commissioner of the Four-Year Plan, the program readying Germany for all-out war; Economic Minister Hjalmar Schacht now reported to him. Göring was to reorganize the economy: continue rearmament, amass resources—particularly fuel, rubber, and metal—cut unemployment, boost harvests, develop the autobahns and other public works, and stimulate coal and other industrial production. “Trust this man I have selected,” the Führer announced. “He is the best man I have for the job.”

Göring also ran Germany’s foreign exchange reserves; no corporation purchased imports without his say-so. The impecunious flyboy of the 1920s had transformed himself into one of Europe’s richest men. But he wanted more. He spun himself an empire through bribes, favors, and secret deals. When German iron ore and steel production under-performed, he set up an outfit to absorb independent operations in the Ruhr Valley and in Austria—hence his enthusiasm for the March 1938 Anschluss that incorporated Austria into the Nazi Reich—and monopolized the Reich’s steel sector. The move made him one of Europe’s, if not the world’s, biggest industrialists.

The all-powerful and autocratic Hermann Göring Works, or HGW, evolved into a holding company. HGW owned 53 percent of arms maker Rheinmetall, 78 percent of auto firm Steyr-Daimler-Puch, and 100 percent of gun manufacturer Steyr Guss-Stahlwerke, whose holdings included a Swiss arms factory. All ran as before, except that under Göring the companies escaped state intervention, courtesy of his patron, Adolf Hitler.

Wealth and his prestigious position within the Third Reich awarded Göring his own armored train, Asien. His sleeping car featured a huge bathtub; other carriages sported a photographer’s darkroom, a six-bed clinic with operating theater, and a barbershop. Two flat cars carried Göring’s fleet of American, French, and German automobiles and his six-wheel-drive Mercedes W31 Geländewagen convertible. Two freight cars bristling with rapid-fire anti-aircraft Oerlikon cannons provided security.

Simultaneously Göring honed the Luftwaffe, charming and cajoling the best men from military and civil life into his air force. One, General Walter Wever, became the first Luftwaffe chief of staff. The forward-thinking Wever kenned that an air force had two roles: support ground forces,and operate strategically on its own.

Nurtured by bottomless budgets, the Luftwaffe grew quickly, heightening Göring’s inclination to see all things as possible as he ignored unpalatable truths. In 1936, for example, Wever had been planning for a long-range heavy bomber force when he died in a flying accident. Successors Hans Jeschonnek and old-time Göring wingman Ernst Udet lacked Wever’s vision. While Göring was immersed in the Four Year Plan, the Luftwaffe’s general staff scrapped four-engine bomber plans, placing more emphasis on dive-bombers—a vision the Junkers Ju-87 Stuka seemed to confirm in the 1936-1939 Spanish Civil War.

Göring went along with the plan. But by 1940, he was woefully out of touch. He had finished the previous war as a captain, spent more than a decade as a civilian, and in being abruptly elevated to general, missed staff college and the on-the-job education of climbing through the ranks.

No four-engine bomber could dive-bomb, but that was how Udet and Jeschonnek envisioned the Heinkel He 177—a turkey of a design that gobbled time, money, resources, and the lives of their top pilots trying to test-fly it. Nor could the new twin-engine Ju 88 achieve the Stuka’s capabilities. The Luftwaffe headed into war with already obsolescent, mid-1930s era bombers rather than powerful modern ones.

The Luftwaffe also failed to adapt an independent strategic role. Unaware of the problems, Göring boasted to Hitler that his fliers would wipe out British troops retreating across the English Channel from Dunkirk. “Only fishing boats are coming over for the British,” he said. “Let’s hope the Tommies can swim!”

The subsequent air battle laid bare the dive-bombers’ shortcoming: With Messerschmitt Bf 109s protecting them on attacks against buildings, the Stukas ruled, but when the target was a moving ship defended by Supermarine Spitfires and Hawker Hurricanes, the gull-winged predators could not dominate. The Royal Air Force prevailed over the Channel, and 338,000 Allied troops escaped.

The same hubris suffused the Battle of Britain. Göring’s chief intelligence officer, Colonel Joseph “Beppo” Schmid, told his chief only what he wanted to hear: that the Luftwaffe could smash the RAF; that Germany was outpacing Britain’s warplane production; that the Messerschmitt Bf 110 trumped the Hurricane; that the English had but a few hundred fighters. And those antennae along their coast? Third-rate radar.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n fact, Britain had an advanced sensing system and a coordinated air defense—the world’s first—and built planes at twice Germany’s rate. Myth holds that the Battle of Britain was a near-run thing for the defenders, but Göring’s men never came close.

Throughout, Göring meddled ineffectually. In early September 1940, he summoned fighter commanders to Carinhall for a pep talk. The airmen sat dutifully as Göring, puffing a huge cigar, bloviated. “What he said sounded like the script of a movie about World War I,” said Captain Johannes “Macky” Steinhoff, an experienced and successful young fighter pilot. “Biplanes looping, attacking from below, flying so close that pilots could see the whites of their enemy’s eyes. I couldn’t stand it.” Raising a hand, Steinhoff offered the Reichsmarschall a few truths about modern fighter doctrine.

“Young man, you still have a lot of experience to gain and a lot to learn before you think you can have your say here,” Göring replied. “Now why don’t you just sit back down on your little rear end.”

Losing the Battle of Britain proved disastrous, forcing Hitler to turn east far earlier than he wanted and triggering a two-front war. Thus started Göring’s—and the Luftwaffe’s—long, hard slide. Although the Luftwaffe would dominate over the Soviet air force and in 1941-42 enjoy brief glories in the Balkans and at Malta, by the mid-1940s, Göring’s air force was in decline, overstretched, and under-producing. Göring could have retrieved the situation by unleashing Erhard Milch, now a field marshal but still his ruthlessly efficient deputy. However, Göring resented, mistrusted, and repeatedly undermined Milch, and left his less competent pal Ernst Udet in charge of procurement and production. The strain broke Udet, who shot himself in November 1941, leaving a mess never to be sorted out.

Göring and his industrial empire survived, but the Luftwaffe, once German’s spearhead, fell into terminal decline.

At Stalingrad in November 1942 the Soviets encircled 250,000 men of the German Sixth Army. Hitler demanded Göring supply his trapped soldiers by plane but the Luftwaffe botched the job, blackening Jeschonnek’s—and by association Göring’s—record. On February 2, 1943, what remained of the Sixth Army in Stalingrad surrendered. A month later, RAF Bomber Command hit Germany’s industrial Ruhr Valley.

Göring thought he saw a lifeline: jet-powered warplanes able to outrun enemy aircraft. On May 25, 1943, fighter ace Adolf Galland touted the twin-engine Messerschmitt Me 262 jet, which flew 100 mph faster than any Allied piston-engine aircraft. “The bird flies,” Galland told the former fighter pilot. “It flies like there’s an angel pushing.” To get the Me 262 fighting, Göring scrapped Messerschmitt piston engine projects. The Me 262 and other “wonder weapons,” such as the rocket-propelled Me 163 fighter, lent the Luftwaffe enough perceived punch for Göring to persuade Hitler that the Luftwaffe was the tool around which German fortunes would turn once more.

So it was that Göring remained Hitler’s chosen successor almost right up until the end. When Göring left Hitler’s bunker in Berlin on April 21, 1945, headed for Obersalzburg, the Nazi enclave in Bavaria, he assumed he was next in the line of Nazi succession.

That was about to change.

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]itler’s secretary, Martin Bormann, loathed Göring and convinced Hitler that a telegram Göring sent him on April 23, suggesting he take over Germany’s leadership since Hitler had lost his freedom of action, revealed that his longtime deputy was a turncoat. That same day, the Führer authorized Göring’s arrest. But not long after the SS came knocking, Hitler, Bormann, and the Third Reich were dead. Göring’s captors held him at his childhood home south of Salzburg until May 6.

Göring sent an aide with a letter to Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower, seeking a face-to-face meeting. The next morning, after hearing that an American general was at a castle about 50 miles away, Göring set off in his usual cavalcade. The U.S. Army officer in question, Brigadier-General Robert I. Stack, informed that Göring wanted to surrender, set off leading a task force to accept it. The motorcades met mid-way. After trading stares, the American motioned to Göring to get into his vehicle. “Twelve years,” Göring muttered. “I’ve had a good run for my money.”

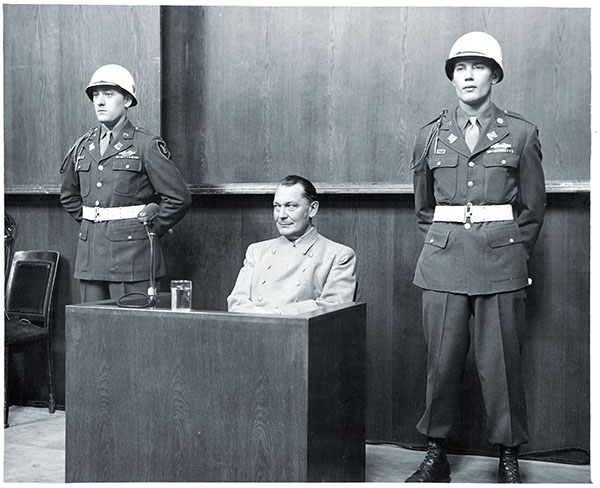

During his 18-month incarceration and trial, Göring lost weight, detoxed, and demonstrated acute intelligence, guile, wit, and even charm. He befriended Lieutenant Jack G. Wheelis, a burly guard and fellow hunter from Texas, and Ludwig Pflücker, a physician. In court, Göring ran rings around his prosecutor, made Justice Robert H. Jackson look a fool, and often provoked onlookers to laughter. But he failed to win one final battle. Certain he was doomed, Göring—hating the idea of dangling from a noose like common criminal—lobbied to go before a firing squad, a death befitting a hero and martyr. The Allies refused his petition.

With the climb to the gibbet two hours away, the former Reichsmarschall unscrewed a brass cartridge case he had concealed and retrieved a glass vial of cyanide. The capsule’s source remains a mystery—Pflücker, or perhaps Wheelis. Göring placed the ampule in his mouth between two molars. He lay on his metal bed, blanket to chest, arms visible atop the cover as his jailors required, and bit down. His gasp drew guards, but too late. The Third Reich’s second-most-important Nazi died, one eye open, one squeezed shut. As his heart stopped, Hermann Göring appeared to be winking.

Originally published in the July/August 2016 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.