British Squadron Leader Lance C. Wade, leading a group of eight Supermarine Spitfire Mark VIIIs, was not expecting to encounter enemy aircraft as his Royal Air Force patrol neared the Italian coast near Termoli on October 3, 1943. Suddenly the RAF fliers sighted Focke Wulf Fw-190As at 12,000 feet. Wade led his fighters from 6,000 feet in a climbing turn in hopes of approaching the enemy planes from their blind spot in the rear and below. After gaining this position and approaching unseen to within 200 yards, Wade destroyed the rearmost Fw-190 with a burst of cannon fire. He then moved behind the next fighter, and with another burst sent the enemy plunging earthward.

The remaining German pilots broke in all directions, trying to escape. Diving after a fleeing Fw-190, Wade heavily damaged it, but he did not see it crash. German records subsequently revealed that III Gruppe of Schlachtgeschwader (battle wing) 4, or III/SG.4, had lost at least one of its Fw-190 fighter-bombers in that fight, and the pilot, Sergeant 1st Class Peter Pellander, had been killed. With the confirmation of those two victories, Wade ended his second combat tour. His score had risen to 25, making him the leading Allied fighter ace of the Mediterranean Theater of Operations at that point.

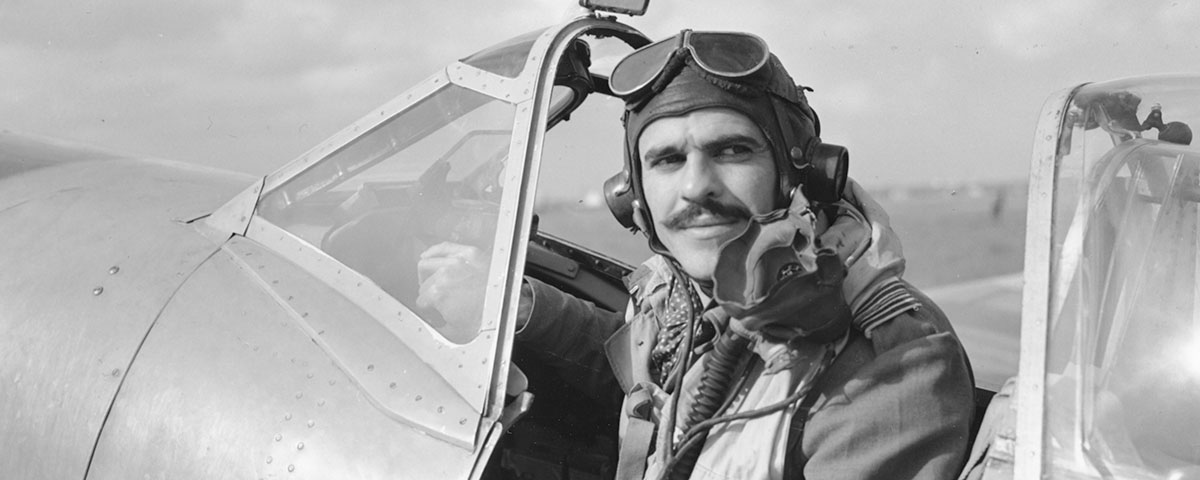

I first encountered Lance Wade by accident several years ago, when I was searching for World War II history books and visited a used book store owned by Henry Johnson. That day turned out to be lucky for me in more than one way. I found several new books for my library, and I also learned about an American-born ace who had slipped through the cracks in books about World War II. As I was rummaging through works on the European air war, Johnson said to me: ‘My Uncle Bill Wade’s son was a Royal Air Force fighter pilot in World War II. His name was Lance Wade, and he shot down over 40 Axis aircraft. I listened politely but initially attached little credibility to his claim, for I had already been studying the air war for many years and thought I could readily recognize the names of high-scoring Allied fighter aces. Johnson went on to tell me that the 40-plus kills were in Wade’s logbook, but not his official record. He also explained that these were not confirmed, as Wade had flown in the desert war of North Africa, and many of his kills had lacked witnesses. But Johnson claimed that the RAF had credited Wade with 25 confirmed victories.

I listened to the bookstore owner’s story, still in doubt, then told Johnson I was not familiar with any pilot named Wade and asked if he knew of any books about him. Johnson explained that because Wade remained in the RAF after the United States joined the war, and he died in a flying accident before the conflict ended, the young pilot’s achievements had not been widely publicized after his death.

When I returned home, I could not get Johnson’s tale off my mind. Going to my bookshelves, I picked up Edward H. Sims’ The Greatest Aces, which contains the semiofficial records of air warfare. As expected, I did not find Lance C. Wade listed in the American aces of World War II, nor in the listing of RAF aces. But then I spotted a footnote at the bottom of a page: This list does not contain one of the Royal Air Force’s greatest fighter aces, Lance C. Wade, an American who volunteered in 1940 to fly and fight for England. Sims added that Wade was one of the highest-scoring Americans in the air war, with 25 confirmed kills, also noting that he died in an accident in 1944.

A product of the east Texas hill country who came of age during the Depression, Lance was born in 1915 in Broadus, a small farming community near the Texas-Louisiana border. The second son of Bill and Susan Wade, he was actually given the name L.C. at birth. In fact, he became Lance C. Wade only after the RAF demanded that he list a name rather than initials — he called himself Lance Cleo Wade just to satisfy regulations. In 1922 the family moved to a small farm near Reklaw, Texas, where he went to school and helped with the farm work. Family members recalled that whenever an airplane flew over, Wade would stop whatever he was doing and say, Someday I will fly. In 1934 at age 19, Wade traveled to Tucson, Ariz., to take advantage of a New Deal program, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which provided jobs for young men. For Wade, however, the CCC work turned out to be much like the farm work he thought he had left behind — driving a team of mules, building roads and planting trees in a national forest.

With war clouds looming, Wade earned a pilot’s license and acquired 80 hours of flying time. License in hand, he tried to join the U.S. Army Air Corps, only to be turned down because of his lack of education. Undeterred, he was soon plotting to join the RAF.

Due to heavy losses during the Battle of Britain, the RAF had started recruiting American pilots for its war effort. Fearful that he might be rejected again, Wade submitted a fictitious rsum in which he claimed that he had learned to fly at age 16, when he and three friends had purchased a plane and a World War I flying buddy of his father’s had taught them to fly. Wade also said that his father had been an ace in World War I. Years later, on hearing that story, Wade’s cousin Henry Johnson laughed and said that the highest Uncle Bill (Wade’s father) had ever been was the top rail of his fences, and that the family was unaware of Wade’s ever owning an airplane. Whatever the facts, in December 1940 Wade was accepted by the RAF.

Britain’s recruitment program resulted in 240 American pilots who flew and fought for England. Most of those men served with Nos. 71, 121 and 133 Eagle squadrons, which were made up of American volunteers. In the course of their service, members of the Eagles destroyed 7312 Axis aircraft and earned 12 Distinguished Flying Crosses (DFCs) and one Distinguished Service Order (DSO). The battle-tested Eagles also provided the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) with valuable combat experience after the United States joined the war. Wade, however, did not serve with the Eagle squadrons but with the regular RAF squadrons, and as a result his awards and victories are not included in the Eagle tally.

Soon after being accepted in the RAF, Wade was sent to No. 52 Operational Training Unit (OTU). Units such as these provided pilots a few weeks’ training in the aircraft that they would fly in combat — in Wade’s case, the Hawker Hurricane. After completing his OTU training, Wade flew a land-based Hurricane Mark I off the British aircraft carrier Ark Royal to the beleaguered island of Malta. His was one of 46 Hurricanes sent as reinforcements to the island. Because of the need for fighters in North Africa, 23 Hurricanes were flown to Egypt, where Wade joined No. 33 Squadron in September 1941 as a pilot officer. After the unit received replacement pilots and aircraft, it was deployed to Giarabub airfield, located in the Libyan desert, a fly-infested wasteland of sand, rocks and brush. The mission of No. 33 Squadron was to provide close air support for the upcoming British offensive, dubbed Operation Crusader, scheduled to be launched on November 18, 1941, against the German Afrika Korps.

Number 33 Squadron was equipped with the Hurricane Mark I and later the Mark II. Hurricanes were the workhorses of the RAF during the Battle of Britain, responsible for attacking German bomber forces while the more advanced Spitfires took on the enemy fighters. The Hurricane was a transitional fighter, with thick wings and a steel-and-wood frame covered with fabric. The lack of streamlining resulted in a design that had little room for improvement; even equipped with more powerful engines the Hurricanes did not show a dramatic improvement in their performance. In fact, the Hurricane of the desert war was nearly 100 mph slower than the Luftwaffe‘s Messerschmitt Me-109F.

The Hurri was not without good points, however. Many pilots believed a Hurricane could outturn the Me-109, and it was a stable gun platform — which made it easier for Hurricane fliers to achieve hits on opposing aircraft. The Hurricane’s wide-tracked landing gear also made takeoffs and landings on unimproved desert fields safer.

The key to success in the war in North Africa was controlling the airspace. The RAF faced two experienced and well-equipped foes: Italy’s Regia Aeronautica and the German Luftwaffe. Many Italian pilots had been flying combat since the Spanish Civil War, and their equipment was equal to that of the RAF. Luftwaffe aircrews were considered the best in the world; they included many veterans of the Spanish Civil War and earlier campaigns of World War II. One of No. 33 Squadron’s principal opponents was the Luftwaffe‘s Jagdgeschwader 27, a fighter wing commanded by Captain Eduard Neumann, one of Germany’s outstanding air combat leaders. Furthermore, the pilot many Luftwaffe leaders considered the best fighter pilot of the war, Hans Joachim Marseille, flew with I/JG.27. Marseille destroyed 158 British and American aircraft.

Commanded by Squadron Leader J.W. Marsden, No. 33 Squadron had been brought up to strength with replacement planes and pilots to support Operation Crusader. The offensive’s purpose was to relieve the British Tobruk garrison and to destroy Axis armored forces commanded by German Maj. Gen. Erwin Rommel, the famed Desert Fox. Crusader was scheduled to begin early in the morning of November 18, and No. 33 Squadron’s assignment was to attack El Erg airfield, located deep in the Libyan desert. As the Hurricanes approached the enemy airfield, three Italian Fiat C.R.42s jumped them. Despite the fact that the C.R.42 was one of the most advanced and maneuverable biplane fighters ever produced, with a top speed of 270 mph, Wade managed to shoot down two of the Italian planes, while the other C.R.42 was downed by his squadron mates.

Four days later, on November 22, nine Junkers Ju-88A bombers of I Gruppe, Lehrgeschwader (training wing) 1, with supporting Me-109s, attacked Allied airfields in the area. Given warning of that attack, No. 33 Squadron managed to scramble six Hurricanes to intercept the enemy formation. The squadron destroyed two Ju-88s, while Wade heavily damaged another Ju-88 in that same fight. After landing and servicing its fighters, No. 33 was ordered to intercept another enemy formation, this time made up of Italian Savoia-Marchetti S.M.79 trimotor bombers. Displaying the aggressiveness that soon earned him the nickname Wildcat Wade, He destroyed one S.M.79 and teamed up with another pilot to bring down a second. On November 24, Wade and his wingman intercepted a flight of S.M.79s with C.R.42 escorts and, in a low-level fight over the desert, Wade notched up another S.M.79. That afternoon he shot down another C.R.42, thus achieving ace status in his first week of combat.

On the morning of December 5, 1941, No. 33 Squadron was ordered to make an early morning attack on the Axis landing field at Agedabia. The squadron mounted its attack from the east so that the glare of the morning sun offered some protection from groundfire. As Wade approached the enemy landing field, he concentrated his fire on an S.M.79 parked near the flight line. When he roared over the damaged enemy bomber, it exploded and heavily damaged his Hurricane. Fighting to keep his plane in the air, Wade struggled on for about 20 miles before setting down in the desert. In an attempt to help, Sergeant H.P. Wooler landed his own aircraft nearby, but Wooler’s Hurricane was damaged during the landing, and he was unable to take off afterward.

Now there were two British pilots stuck in the desert without food or water. Fortunately, the Desert Air Force was prepared for such an emergency. If stranded airmen could be located, they were supplied with essential rations by air. The fliers were given directions on where to head, and if the men could find firm sand to facilitate a landing by another aircraft, a plane would be sent in to rescue them. Wade and Wooler were among the lucky ones, as they were quickly spotted and supplies were airdropped to them. After walking back to base, Wade and Wooler officially became members of the Late Arrivals Club, which meant they could wear a special patch on the left breast of their flying suits.

During Wade’s first tour of duty from September 1941 to September 1942, the Desert Air Force took heavy losses due to the limitations of their outdated Hurricanes. But despite his plane’s obvious shortcomings, Wade’s victory total continued to rise. He also became the unofficial deputy commander of No. 33 Squadron.

Wade’s last week of his tour came during a period of intense air combat. That action started on September 11, 1942, with a large dogfight between Hurricanes of Nos. 33 and 213 squadrons and the Me-109s of I/JG.27 and II/JG.27 that were escorting Junkers Ju-87s on a dive-bombing mission. The Hurricanes were supported by the two new Spitfire squadrons, Nos. 145 and 610. In a swirling fight, Wade destroyed a Ju-87 on the 11th. Five days later, he tangled with a highly skilled Italian pilot flying a Macchi M.C.202, who damaged his Hurricane. This was the first time an enemy pilot had hit Wade’s fighter in a year of air combat, and he conceded that the enemy pilot was good. As his tour came to an end, Wade was sent home for a well-deserved rest. His score then stood at 15 confirmed kills.

The Texan RAF pilot’s exploits had been widely reported in U.S. newspapers, and now the American press corps clamored to meet the man who had become a high-scoring ace and also been invited to tea with Britain’s royal family. Upon his arrival in New York, he held a press conference at Rockefeller Center and was featured in the October 14, 1942, issue of The New York Times. After touring the big city, Wade returned to east Texas to a hero’s welcome. An auto dealership offered him the use of a new car during his leave, which he politely refused, and he also received invitations to speak throughout the region.

During his time at home, Wade spoke to his brother Oran about some of his experiences in the desert war. Oran later recalled hearing how on one mission Lance had become separated from his flight by three Me-109s and in a swirling low-level dogfight had shot one down and damaged another. He reportedly lost the third by flying down a desert gully. There had apparently been no witnesses to confirm what had happened, however. He also told Oran that enemy pilots seemed to have recognized his aircraft during the last half of his tour and started avoiding him. That may have been thanks to the fact that Wade’s Hurricane was distinctive — decorated with his own design, a fighting cock, or rooster, standing in front of an American flag. That same aggressive-looking bird would later be adopted as the emblem of the U.S. Army Air Forces’ 4th Fighter Group, which included many former Eagles in its ranks.

Wade was next sent to Wright Field to test new American fighters. He later reported to the RAF delegation in Washington and was introduced to President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House.

Wade eventually returned to North Africa to take command of No. 145 Squadron, which was equipped with Spitfire Mark Vbs. By the time he joined the squadron in January 1943, he had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and a bar (representing a second DFC). The squadron’s assignment was to keep enemy fighters from attacking the Hurricanes and Curtiss P-40 fighter-bombers. His new unit was made up of pilots of many nationalities: Britons, New Zealanders, Argentines, Trinidadians, Canadians, South Africans and Australians. Also attached to the unit was the Polish Fighting Team, made up of 15 expert pilots who had been fighting the Germans since the beginning of World War II. Led by Stanislaw Skalski, Poland’s leading ace of the war, that group had a reputation for being difficult to manage. But under Wade’s leadership, the squadron developed into a highly successful combat unit.

Throughout the North African campaign, fighter units were commonly based near the front lines so that they could respond to ground units’ requests quickly. Sometimes enemy ground units broke through Allied lines and overran the landing fields where the fighters were assigned. On February 25, 1943, German artillery fire began hitting the airfield where No. 145 Squadron was stationed. In a hasty scramble to save aircraft and personnel, Spitfires, jeeps and trucks raced from the field. The squadron managed to escape with all its aircraft except for one that had been under repair. Even so, Wade’s own fighter had its starboard wing damaged by an exploding shell, but he flew the damaged plane to El Assa and somehow came down safely.

As March 1943 ended, No. 145 Squadron had developed into an effective fighter unit, credited with 20 enemy aircraft destroyed for the month. (In comparison, all the RAF units in the Mediterranean theater were credited with 59.) The month also marked a turning point in the air war, with enemy aircraft becoming increasingly difficult to find. Wade had started the month off by downing an Me-109 over Medenine that was confirmed later — probably killing a Sergeant Ertl of 3/JG.53. He went on to take out another Me-109 north of Mareth on the 22nd and two south of Sfax on the 23rd. During that same period he also received news that he had been awarded a second bar to his DFC.

In September 1943, No. 145 Squadron provided support for the invasion of Italy. It was during the Italian campaign that Wade took part in what may have been his most notable aerial combat. That battle occurred on November 3, 1943, while he and a wingman were patrolling the front lines and encountered a large flight of Fw-190s of II/SG.4 attacking a target. Wade radioed for help but did not receive a response. Nevertheless, he and his wingman decided to attack the enemy formation. In the dogfight that followed, an Fw-190 crossed in Wade’s front, offering him a brief opening, and with a burst of cannon fire Wade shredded the German plane.

As the engagement continued, Wade damaged two more Fw-190s before making a low-level escape. Both he and his wingman survived the fight. Wade had been too hard pressed to really determine what became of the enemy planes he hit, so they were credited to him as three damaged, but II/SG.4 subsequently reported that Sergeant Georg Walz had been killed by Spitfires near Termoli.

As Wade’s second tour drew to a close, a ceremony was held in his honor. Air Vice Marshal Harry Broadhurst, air commander for the RAF’s Mediterranean theater and himself a high-scoring Hurricane ace from the Battle of Britain, reviewed No. 145 Squadron on that occasion. In his remarks, Broadhurst pointed out that Squadron Leader Wade was the most successful commander of No. 145 Squadron from both World War I and World War II. Wade was subsequently promoted to wing commander, with the rank of lieutenant colonel, and posted to Broadhurst’s staff.

Wade’s future looked bright at that point, given his new rank and assignment. His private life was also prospering, as he had become engaged to marry a young British woman. Sadly, all that bright promise was about to come to a tragic and premature end.

Missing his old squadron mates, Wade decided to pay them a visit. On January 12, 1944, he flew a twin-engine Auster light bomber from the theater headquarters to No. 145’s base at Foggia, Italy. At the end of his visit, Wade climbed into the Auster and took off again. But as his plane climbed from the runway, it suddenly went into a spin and crashed. Wade was killed instantly.

After the war, one of Wade’s friends visited his family and expressed his belief that Wade’s plane had been sabotaged. Whatever caused the crash may never be known, since some RAF crash records of World War II are still classified. Shortly after Wade’s death, news was received that he had been awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

In less than three years, Lance Wade, a former mule skinner from Texas, rose like a meteor to become the leading ace of his theater. After his first tour, Wade had been offered higher rank and more pay to transfer to the USAAF. But he had declined at the time, saying, Thanks, that’s mighty fine, but I’d rather keep stringing along with the guys I have been with so long now. As The New York Times wrote, He strung along with them to the end — the end of his life.

Lance Cleo Wade was buried in a quiet country churchyard just down the road from his boyhood farm near Reklaw. Even in his hometown, there are no markers to honor his remarkable accomplishments, and that seems a terrible shame, given his immense contribution to the Allied air war.

This article, written by Michael D. Montgomery was originally published in the November 2004 issue of Aviation History. For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!

Click here to build Wade’s Spitfire Mk.Vb.