Hannah Duston’s ordeal mercifully ended when she dragged herself into Haverhill, Massachusetts, in the late spring of 1697. In March an Indian war party had swooped down on the New England frontier and abducted the young woman and her newborn daughter. A six-day-old infant stood little chance of surviving a journey to Canada over the frozen New England landscape, so on the outskirts of Haverhill, Hannah was forced to bear witness as an Abenaki warrior dashed out her baby’s brains against a tree. Six weeks into her captivity, Hannah ferociously attacked her captors while they slept. In a thunderclap of gory retribution, armed with a tomahawk, she hacked at and bludgeoned to death an Indian man, two women, and six children. A fellow captive killed another warrior. Hannah scalped all 10 Indians, as much to avenge the murder of her child as to collect the lucrative bounty that colonial officials had offered for scalps. Puritan ministers and lay people alike thanked God for Hannah’s deliverance and for the vengeance she had wrought on the “savages” who had preyed on New Englanders throughout the terrible war that had just subsided.

Recommended for you

While William III of England waged the War of the League of Augsburg (1689–1698) in Europe to roll back Louis XIV’s expansion into the Low Countries, his subjects on the North American frontier fought for their very survival against the French and their Indian allies in what became known as King William’s War. New Englanders proved unable to strike effectively at New France, which emerged from the conflict almost unscathed and completely victorious. The fighting continued intermittently for seven years — from 1690 to 1697 — though Cotton Mather, the Puritan grandee who believed the war marked a manifestation of God’s displeasure with New England, titled his 1699 history of it Decennium luctuosum (The Mournful Decade).

New Englanders decided their only recourse was to destroy New France, or as Reverend Cotton Mather later termed it, the “rookery of evil.”

the beaver wars: ensnared in the conflict

New England was pulled into the war by an ongoing conflict on the North American frontier between the French and the Iroquois League. The two had ensnared themselves in another chapter of the long-running Beaver Wars. This phase began in 1687 when French forces raided deep into Iroquoia, territory that comprised much of what is now upstate New York; in July 1689 the Iroquois League responded, and its warriors massacred the French settlers and some Indians at Lachine, west of Montreal, spitting and roasting some of their victims. New France’s wily governor general, Louis de Buade de Frontenac, feared that if the English colonies leveraged the military might of the Iroquois League, they might well conquer New France. He concluded that only offensive actions could keep Canada’s enemies at bay. By this late point in the generations-long Beaver Wars, the Iroquois League itself teetered on the brink of a civil war among pro-French, pro-English, and neutralist factions. The centerpiece of Frontenac’s strategy thus became breaking the Covenant Chain, the series of agreements between the English and the Iroquois League that had kept the peace with the Iroquois and the majority of other Indians in the northeast (the Abenakis, Maliseets, and Mi’kmaq).

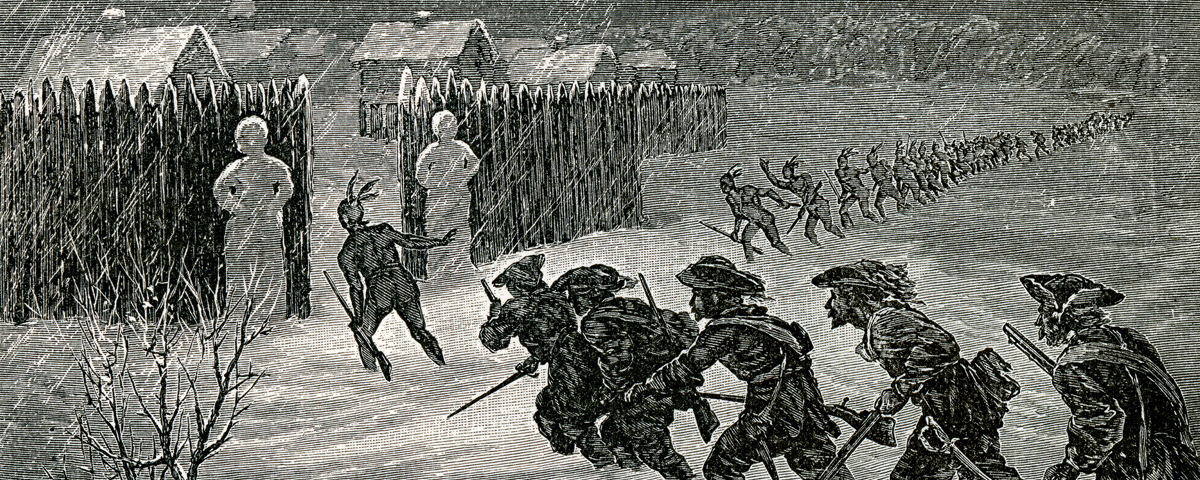

The French struck first at Schenectady, New York, in early February 1690. Frontenac unleashed 110 of his colony’s rugged milice (militia) in the height of winter, when the English least expected an attack. Many of the milice were the legendary coureurs des bois, literally “woods runners,” whose time on remote frontiers had inured them to physical hardship; 96 pro-French Iroquois agreed to accompany the milice. The Frenchmen wanted to destroy Albany, the main English entrepôt for the fur trade in the west, but the Indians preferred Schenectady, 15 miles farther northwest, as the place to balance the ledger for the horrors perpetrated on their Iroquois cousins at Lachine. On the night of February 9, 1690, the raiders found the settlers asleep and just two snowmen guarding Schenectady’s gates. Upon the signal of an Indian war cry, the raiders attacked, slitting the throats and crushing the skulls of 60 men, women, and children and taking 27 male prisoners. Pro-English Mohawks pursued the raiders almost as far as the outskirts of Montreal before they realized that discretion was the better part of valor and retreated to New York.

King william’s war: causes and carnage

Frontenac next focused his attention on the New England frontier. In March he turned loose New France’s professional soldiers, the troupes de la marine, and the Mi’kmaq of Acadia. The marines were under the direction of Joseph-François Hertel de la Fresnièr. Thanks to their service against and alongside Indians, they had begun to master the art of petite guerre, what today we would recognize as guerrilla warfare. On March 27, 1690, Hertel’s war party struck Salmon Falls, New Hampshire, where it massacred 34 settlers, took 54 others toward Canada, and burned the village. The militia, pursuing the raiders blindly, walked into Hertel’s ambush on March 28. They extracted themselves from near-disaster but left the Salmon Falls captives to the mercy of the Mi’kmaq. On the way to Montreal, the Indians tortured to death most of their prisoners. The marines may not have participated in the horrific tortures, but they didn’t try to stop them either.

New Englanders decided their only recourse was to destroy New France, or as Reverend Mather later termed it, the “rookery of evil.” In April Massachusetts governor Sir William Phips, a wealthy shipbuilder and treasure hunter who possessed little military experience, led 700 militia and seven ships from Boston against Port Royal, the small outpost on the Bay of Fundy that served as the capital of the colony of Acadia. On May 11, he took Port Royal after an almost bloodless siege. Although Phips promised that the Acadians would be given hors de combat and thus unharmed, his men sacked the town and took the French garrison to New England as prisoners of war. Bostonians welcomed Phips as a conquering hero, and Massachusetts opened the colony’s coffers for a late-summer amphibious expedition up the Saint Lawrence River to Quebec. Connecticut’s governor, Fitz-John Winthrop, received authorization from his colony to lead 750 militia through the Lake George–Lake Champlain–Richelieu River corridor against Montreal. The Iroquois promised 1,800 warriors would join him.

But while the English planned and prepared, the French acted. On May 16, 1690, a combined force of 500—marines under Hertel and Abenakis led by Jean-Vincent d’Abbadie de Saint-Castin, a French army officer whom the Indians had adopted as one of their war chiefs—reached Falmouth (today’s Portland) on Casco Bay. Their target was Fort Loyal, the easternmost New England outpost in Maine. The English militia assumed they were dealing with a small raiding party, so 30 of them — most of the garrison — sallied forth from the protection of the fort. The marines and Indians easily dispatched and scalped all but four of them. The fort’s commander, Captain Sylvanus Davis, asked Hertel for terms. Hertel assured him that he would allow all the English to travel unmolested to Portsmouth. Whether he intended to keep his word remains a mystery, but Saint-Castin and the Abenakis killed and scalped the English wounded and took several captives, including Davis. The French and Indians’ so-called treachery enraged New Englanders. Few wanted to admit that at about the same time, Phips’s Boston men were laying waste to Port Royal.

Disappointment, disaster and smallpox

By August 1690, the English had convinced themselves that the tide was about to turn. High hopes went with Winthrop’s small army as it marched to Lake Champlain. Once there, however, the English discovered that the merchants of Albany had failed to deliver the boats and supplies promised, and just as damningly, only 120 Iroquois warriors, rather than the 1,800 expected, had appeared. With smallpox racking his army and his troops deserting in droves, Winthrop decided to return to Albany. Captain John Schuyler convinced some of the Iroquois to join him and some militia on a raid to Montreal. They reached Prairie-de-la-Madeleine (today’s La Prairie), across the Saint Lawrence River from Montreal, on August 23. Once there, the Iroquois refused to attack the blockhouse that protected the village, so after taking some prisoners — two of whom they killed — and slaughtering La Prairie’s cattle herd, Schuyler’s band returned to New York. The sum total of the English response to Frontenac’s campaign amounted to killing 120 head of cattle.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

If Winthrop’s campaign was a disappointment, Phips’s proved a disaster. The English did not arrive at Quebec until October, as winter barreled down on Canada. Phips duly demanded that Frontenac surrender; the governor general retorted that his answer would come “from the mouths of my cannons and muskets.” Phips lackadaisically landed 1,200 militiamen and a large part of his artillery train downriver of the citadel, and his four warships bombarded Quebec. After several days during which the English expended their ammunition to no effect, Phips gathered his troops and sailed for Boston, leaving behind several cannons for the French to claim as trophies. Storms slammed the fleet and sank several vessels, and smallpox broke out among the troops on the cramped and filthy transports. Over 1,000 men, nearly half of Phips’s army, perished before the armada entered Boston harbor.

oh, canada!

The campaign of 1690 had shown Frontenac that the English were powerless to stop his Indian raiders, so in 1691 he doubled down on using them as Canada’s first line of defense. The bounties he placed on scalps provided all the motivation that innumerable war parties needed to swarm over the frontier, capturing, killing, and scalping as they went. The “war” at that point hardly deserved the term; it had devolved into a string of gruesome murders that terrorized New England.

The English tried to stanch the Indian onslaught with another campaign against Montreal in the summer of 1691. In June Peter Schuyler, John’s brother, took his turn, leading 120 militiamen with 145 Indian allies against Canada. The question no one on the English side seemed prepared to ask was whether the Iroquois were serving as the English proxies or the English had become the New York Indians’ auxiliaries in their war with the French. Schuyler’s small army left its canoes and boats at Fort Chambly on the Richelieu River and marched west overland to La Prairie. There, French marines vigorously counterattacked, forcing Schuyler to run for Albany only to fall into a French ambush south of Fort Chambly. He narrowly avoided disaster: He had lost a quarter of his troops but speciously claimed that he had killed 200 French and Indians. The raid did nothing to relieve the pressure on the New England frontier.

More suffering was in store for those living on the frontier in early 1692. On January 24, 300 Abenakis under chief Madockawando and Father Louis-Pierre Thury attacked York, Maine. In what became known as the Candlemas Massacre, the Indians repeated the now familiar pattern of frontier war: They burned the village, killed 100 English settlers, and took 80 captives.

Frontenac brilliantly mixed diplomacy and violence to outmaneuver the English at every turn

new york state of mind

Frontenac then switched his operational focus to the Iroquois villages in New York. In both 1692 and 1693 the French and their Indian allies raided Iroquoia, destroyed Mohawk “castles” (villages), and carried hundreds of captives off to Canada. Following the January 1693 attack, Peter Schuyler and the Albany militia joined the Mohawks when they pursued the raiders. For the first time in the war, colonial militia performed relatively well, but the French and their Iroquois allies escaped with only a few casualties and most of their prisoners. The French successes of 1693 convinced many within the Iroquois League that the only means for its survival was a peace treaty with the French. The Covenant Chain was being torn asunder, and it was the Iroquois link that had snapped first. Representatives from the English colonies rushed to Albany in the spring of 1694, offering the wavering Iroquois arms and ammunition to sign a new treaty of friendship with them, but it soon became apparent that their efforts were too little too late.

Frontenac brilliantly mixed diplomacy and violence to outmaneuver the English at every turn. He gave the Iroquois League time and breathing room to consider its predicament, while disrupting the Abenaki-English peace talks that had started in late 1693. Father Thury, with Frontenac’s backing, cajoled the Abenakis into continuing the fight. On July 18, 1694, he and two other Frenchmen joined 230 Abenakis and Maliseets in a bloody raid on the village of Oyster River (today’s Durham), New Hampshire. In the orgy of destruction that followed, the Indians killed 104 villagers, burned the village’s buildings and fields, and slaughtered the livestock. Nine days later the same war party fell on Groton, Massachusetts. Twenty-year-old Lydia Longley was among the captives the Indians took. Choosing a path far different than the one Hannah Duston would pick, she did the unthinkable for an English Protestant: She accepted baptism as a Roman Catholic and entered the Congregation de Notre-Dame to become a nun. For the remaining 60 years of her life, she lived near Montreal as Sister Saint-Madeline, English America’s first Catholic nun.

The war entered a lull year in 1695, then in 1696 Frontenac made his final push for both the spoils of war and victory. In August Saint-Castin and the Abenakis joined Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville (whom Frontenac had earlier sent to eject the English from their fur-trading stations near Hudson’s Bay) in a siege of Fort William Henry at Pemaquid, on the central Maine coast. A month later in the most successful English operation of the war, New England’s venerable Indian fighter, Benjamin Church, raided Acadia and occupied it for a week in September. The French campaign in the Maritimes produced more lasting results. In four months of campaigning up and down the Maine coastline and as far as Newfoundland, Iberville sacked 36 settlements, killed 200 Englishmen, took 700 seamen and fishermen into captivity in Canada, and gave the deathblow to New England’s faltering economy. Frontenac, meanwhile, focused on the Iroquois League, specifically the Oneida and Onondaga nations. Close to 2,200 milice, marines, and pro-French Iroquois ascended the Saint Lawrence River to attack the league at its heart, but they found few inhabited castles. The New York Iroquois had fled before their Canadian kin and the French. The message was clear: The collective league had no desire to continue the war.

The war, however, approached its denouement. March 1697 saw the raid on Haverhill that led to Hannah Duston’s drama in the wilds of New Hampshire before word reached North America in the summer that English and French plenipotentiaries had begun peace talks in Holland. The September 1697 Treaty of Ryswick ended the Anglo-French conflict in Europe and North America.

a short peace

With war officially over, the belligerents tried to make sense of their participation in it. Frontenac received the title the “Savior of New France,” though his Indian allies deserved it as much as he did. In the Great Peace of 1701 at Montreal, the Iroquois League, battered both by the French and by factionalism, declared its neutrality in any future Anglo-French wars. The Covenant Chain lay in pieces, and henceforth the English colonies would have only themselves to depend on, but the fighting had shown the militia to be wholly ineffective and near moribund. New Englanders’ hatred of Indians and the French had grown exponentially, which made the putative peace treaties they signed with the Indians all the more distasteful. Some New Englanders demanded revenge; others predicted that another war with the French and the Indians would lead to more mournful years — and Queen Anne’s War, which began a mere five years after King William’s War and lasted nine long years, proved the latter prescient.

John Grenier has written numerous histories on colonial American wars, including The First Way of War and The Far Reaches of Empire. This article was published in the Winter 2016 issue of MHQ.

Send us your comments! MHQeditor@agriffith

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.