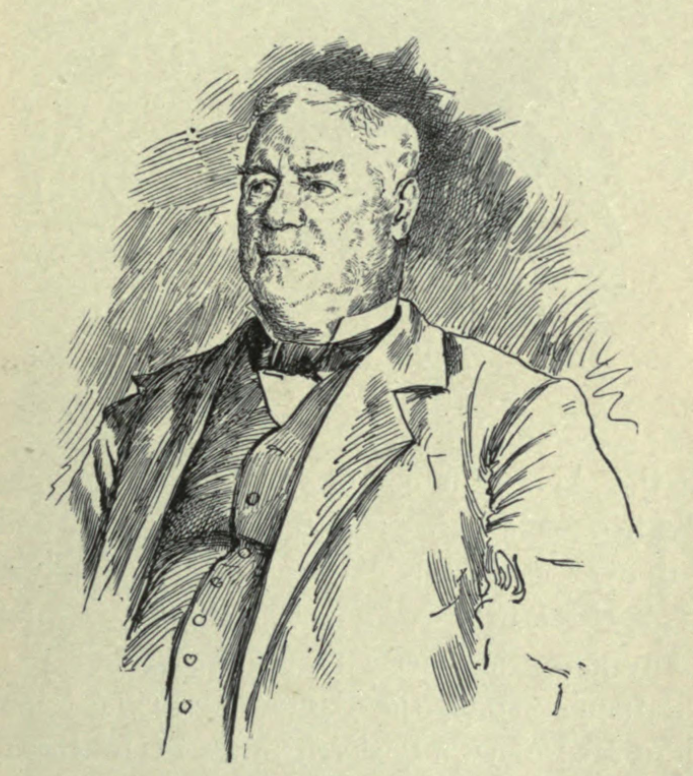

Inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners at the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Center in Oklahoma City in 1996, John Forster was the archetype of pastoral California’s silver dons. A century and a half prior to his induction, Forster, who was English by birth and Mexican by naturalization, had declared his allegiance to the United States and singularly contributed to its acquisition of California.

In 1830, at age 16, John Forster left home in Liverpool, England, to work for his uncle, James ‘Santiago Johnson, at Guaymas, Mexico. After sailing to Valparaiso, Forster lingered for several months seeking passage before continuing on to Guaymas, where his uncle and a job with the trading firm of Johnson and Aguirre awaited.

Forster remained in Guaymas for two years until the expansion of his uncle’s firm required his relocation. He then came overland to California, reaching Los Angeles in June 1833. The following year he began his own trading enterprise, and in 1837 he married Isadora Pico, sister of a future Mexican governor of California, Po Pico. The young couple moved into a house between Spring and Main streets in the Pueblo de Los Angeles, where the first of their nine children was born in 1839.

Forster also assumed the management of Abel Stearns’ Casa de San Pedro in 1840. Stearns, a wealthy Connecticut emigrant, had developed a large warehouse, store and living quarters at the port of San Pedro. There, as Stearns’ agent, Forster traded manufactured goods for articles of local production such as hides, tallow, horns and wines. It was also there that his distaste for the existing Mexican government first emerged. It is a dam’d bore to be put under different restrictions every day by the confounded government, he said. God knows what will come next. Yet that very same government appointed him captain of the port in March 1843. That year he was also granted the 26,000-acre Rancho Nacional. It was his first land, but only a small portion of what would one day become his quarter-million-acre empire on the coast of southern California.

Forster ended his association with Stearns in 1844. The following year he purchased 44 acres and the buildings of the former Mission San Juan Capistrano at public auction for $710. It became his home.

In April 1846, news reached U.S. President James Polk that Mexican troops had crossed the Rio Grande and attacked General Zachary Taylor’s force. The resulting war with Mexico made America’s acquisition of California opportune. On June 30, General Stephen Watts Kearny’s Army of the West left Fort Leavenworth (Kan.) to conquer and take possession. A week later, Commodore John D. Sloat, commander of the Pacific Fleet, annexed California upon the fleet’s arrival at Monterey.

Major John C. Frémont, with his battalion of irregulars, reached San Diego aboard Cyane on July 29 and began marching to Los Angeles. About that same time, José Antonio Pico (Forster’s oldest brother-in-law) and José Antonio Cot acquired the mission of San Luis Rey. Forster traveled from San Juan Capistrano to take formal title of the property for the new owners. As Forster took occupancy, Frémont and his American force rode into view. Forster fled back to San Juan Capistrano, leaving the property in the hands of the alcalde, Juan Mara Marron.

In Forster’s judgment, his taking occupancy of the property thwarted Frémont’s plan to seize the mission for personal gain. He became exasperated against me and swore he would shoot me, Forster wrote in his 1878 work Pioneer Data From 1832. He rode into San Juan Capistrano one or two days later with the determination of capturing and executing me. Frémont and his whole force (Kit Carson, [Alexander] Godey, the Indian company of Shawnees were with him) surrounded the mission buildings at San Juan Capistrano believing that I would attempt to escape. He was savage against me until we had an explanation when he became convinced that I was favorably disposed to the United States, at the same time that I was trying to save the interests of my relatives, the Pico family.

Frémont would have been less favorably disposed had he anticipated that four days later Forster would begin to plan the escape to Mexico of another brother-in-law, Governor Po Pico. For several weeks, Forster hid Pico in the mountains near San Juan Capistrano; then, at an opportune time, Forster outfitted Pico for a dash to the border on September 7, 1846.

Meanwhile, General Kearny’s force had secured Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he left the larger portion of his command. Kearny and his dragoons crossed the Colorado River and entered California in late November. In the pre-dawn hours of December 6, the small American force battled General Andrés Pico (yet another of Forster’s brothers-in-law) and his Californio command (Mexicans born in Alta California) at San Pasqual. The U.S. forces suffered their costliest defeat of the war in California–18 dead and 13, including the general, wounded.

Kearny’s crippled command reached San Diego on December 12 and joined forces with the American naval command under Commodore Robert Field Stockton. Kearny and Stockton planned a military expedition from San Diego to Los Angeles to reclaim southern California from Californio insurgents. On December 29, the two commanders left San Diego with their eclectic force of 55 dragoons, 379 naval Jack-tars and Marines, and 84 mounted volunteers–30 Californians, 10 scouts and 44 officers.

On New Year’s Day, 1847, the makeshift army reached Mission San Luis Rey and came upon Forster, who had ridden from San Juan Capistrano to offer assistance. Forster, though an Englishman and brother-in-law of both the Californio governor and the commander of the insurgents, determined that the pragmatic thing to do was to offer assistance to the Americans. Like other large landowners, Forster recognized that Mexico’s political instability posed a constant threat to his economic interests. Any of three alternatives was preferable: British annexation, independence in the fashion of Texas’ Lone Star Republic, or American annexation. I was desirous of seeing the country under the United States or any stable government, he said. Stockton, more gracious than Frémont, sent Captain Samuel Hensley with Forster to San Juan Capistrano, where Hensley obtained 28 yokes of oxen and a supply of fresh horses. Returning with Hensley, Forster announced his intention of joining the force on the northward march.

On January 5, the army marched to San Juan Capistrano. Forster’s eldest son, 8-year-old Marcos (Marco), was playing with friends in the road as the American force approached. All of the children fled except Marco. Are you afraid? asked Commodore Stockton. No, replied Marco. Stockton invited him to ride, and the boy said that he would like that very much. Marco rode into San Juan Capistrano on the commodore’s horse. As they entered the village surrounding the mission, the band played Life on the Ocean Waves.

When the army marched north from San Juan Capistrano, Kearny and Stockton told Forster that Rámon Carrillo, an officer in Juan Padilla’s band of Californios, had killed two Americans, Thomas Cowie and George Fowler, near Santa Rosa. Anxious to induce Carrillo and his followers to leave the Californio forces, Stockton instructed Forster that should he encounter Carrillo, he was to convey to him the commodore’s promise to provide Carrillo with security–the past would be forgiven and forgotten.

On January 7, the army marched from Santa Ana Abajo, near the town of Olive, toward the Rancho Los Coyotes. As the force crossed the Rio Santa Ana, Forster’s horse lost its footing, and both horse and rider tumbled into the river. I rolled over and got thoroughly wet, Forster recalled. I had to go back to the house to change my garments. Just at this time the Californian reconnoitering party rushed in, and I expected to have been made a prisoner, but the commander of the party happened to be Rámon Carrillo, the very man I had been wanting to see.

Forster delivered the message from Stockton. Carrillo hesitated, not wanting to forsake his countrymen. Forster hoped that Carrillo might change his mind if he could be handed Stockton’s guarantee in writing. Carrillo agreed to meet Forster later that night at the ranch of Tomás Colima. Promising to return, Forster rode north to Rancho Los Coyotes, the American encampment. Remarkably, Forster found the army there in the midst of a fiesta, staged by the ladies of the rancho. The California ladies, Forster wrote, were soon whistling around in the giddy mazes of the waltz, with their taper waists encircled by arms, which on the day following, would beyond a doubt be dealing death blows upon friends and relatives. But it made no odds to the Ladies, there was music and there was a chance for dancing, and at it they went as if this was the last night in the world.

The dancing continued as Forster huddled with Stockton, who provided him with a written guarantee for Carrillo. Accompanied by Don Juan Avila, Forster returned to Colima’s ranch, but Carrillo was gone. They searched for his encampment on the banks of the Rio San Gabriel. (The great flood of 1867 later cut a second channel in the flood plain. The old channel became the Rio Hondo. The new channel is the present-day San Gabriel.)

My horse (a favorite one) was now completely fagged, and I saw it was necessary to procure a fresh one before I could proceed to the bank of the river, Forster recalled 30 years later. The caponera [corral] of the ranch was near, and we drove into the corral and selected a horse, leaving mine there, repaired to the house to inform the owner or someone representing him of what I had done, but found the house abandoned. There was only one old Indian who could hardly make himself clearly understood in Spanish. From him I learned that every man in the place, and everywhere else, had been pressed into military service, and the Californian forces (about six hundred strong) were ambushed in the willow thickets and mustard patches near what is now the town of Gallatin (about 10 miles south of Los Angeles). Avila rode on in an effort to locate Carrillo, while Forster rode back to tell Stockton and Kearny of the impending ambush.

The information that Forster had inadvertently uncovered proved accurate. General José Mara Flores moved his army from San Fernando to Lemuel Carpenter’s La Jabonera (Soap Works) crossing of the Rio San Gabriel (near the present-day crossing of the Rio Hondo by the Santa Ana Freeway). The Californios waited in ambush for the Americans.

At Rancho Los Coyotes, Forster informed Stockton and Kearny of what was in store for them if they continued their march in the contemplated direction. The next morning the American force stood at attention while Stockton told them of the likelihood of a fight. He called upon them to deport themselves in accordance with those other Americans who, on that very day (January 8) 32 years earlier, had achieved victory over the British at New Orleans during the War of 1812. The watchful army then started its march toward the Rio San Gabriel and the awaiting ambush.

The Americans marched to within 600 yards of the east bank of the river, just out of range of the Californio cannons. Suddenly they veered to the north and raced to reach the Paso de Bartolo crossing of the river. In Forster’s judgment: This movement entirely disconcerted the Californian forces. They became disorganized and in that condition rushed to meet the commodore at the upper crossing and only succeeded in having a small scattered portion to face the Americans at the ford.

That afternoon the Californios and the American forces fought the Battle of the Rio San Gabriel. Don Bernardo Yorba of Santa Ana rode to a high point in the hills to watch the engagement. Yorba wrote: I saw there had been nothing decisive except the Californians rather gave way, a portion of the Californians made a charge that seemed for a time to have broken the American line. But as soon as the dust cleared I saw the Californians retreating, and from what I learned afterward, had the charge been simultaneous of all Californian forces, the American lines would have been broken, and there is no telling what the end might have been.

The battle ended abruptly when the Americans gained the high ground on the west bank of the river. The Californios abandoned the field. The victory cost seaman Frederick Strauss his life. The Americans fought a brief action the following day, and Los Angeles capitulated on January 10. The success at the Rio San Gabriel proved the key to re-establishing American control of southern California. John Forster’s information, as he later noted, had proved crucial in gaining the victory: I had not then, and have not now any doubt that if the American force had passed by the road they were traveling upon, they would have been fallen upon by the Californians in force and perhaps utterly annihilated, for there was no room there where they could protect or defend themselves from a sudden attack of cavalry. Aware that any further resistance by the Californios would be futile, Forster returned to San Juan Capistrano.

Forster anticipated that both he and California would prosper under the United States. He was not disappointed. The California Gold Rush created a demand for southern California cattle, and Forster profited by supplying that demand. Steers, previously worth only the value of their hides (about $2), soon brought $50 and more in San Francisco. The gold rush also fostered demand for statehood among the swelling population of the mother lode country. Typical of the residents of sparsely populated southern California, Forster opposed statehood but would support territorial status. Forster was selected as one of San Diego County’s two delegates to the 1849 convention at Monterey, but on learning that the northern California delegates vastly outnumbered his southern colleagues, he chose not to attend. Northern Californian delegates sought statehood, and in 1850, California secured it.

At the beginning of the 1860s, Po Pico, Forster’s quixotic brother-in-law, was in financial trouble. Burdened with debt from bad investments, gambling and a decline in cattle prices, the former governor sought Forster’s assistance. Forster loaned money to meet Pico’s property taxes. Po’s brother Andrés, the California general at San Pasqual, suffered similar monetary shortcomings. In 1862, to thwart collectors, Andrés conveyed all of his land in California, including a half interest in the family’s Rancho Santa Margarita, to brother Po. Alas, the former governor and the ex-general could gamble money away at a remarkable rate. In February 1864, Forster purchased Po’s 133,000-acre Rancho Santa Margarita y Las Flores y San Onofre, which included Andrés’ prior interest. He paid $14,000 and assumed the $42,000 mortgage in favor of the San Francisco firm, Pioche and Bayerque. The ranch adjoined Forster’s own Rancho Misin Vieja y Trabuco of 79,000 acres; Forster thereafter ruled over a vast 212,000-acre empire, the largest single-owner ranch in southern California.

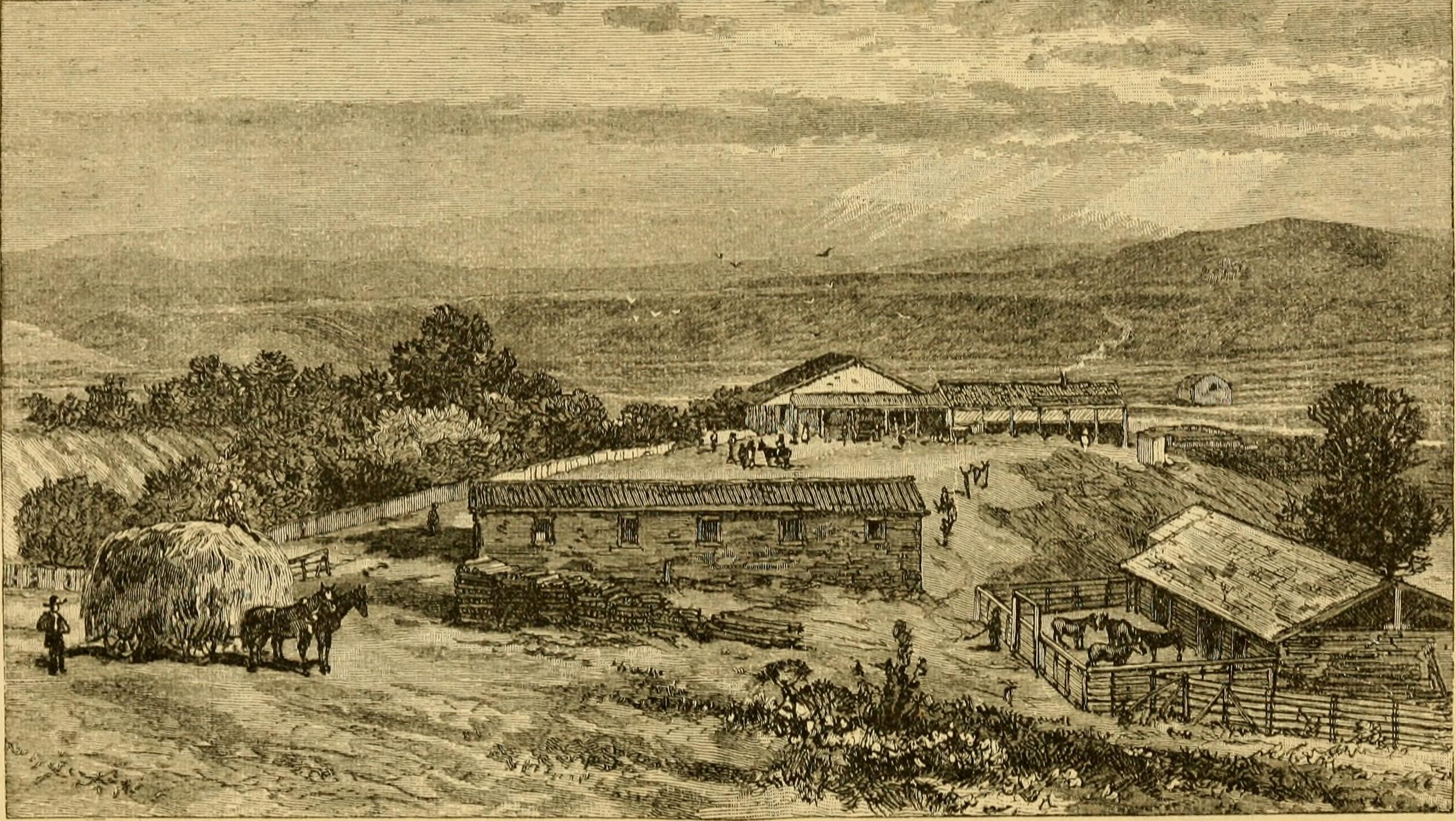

By late 1864, Forster had spent an additional $30,000 improving the ranch. He brought floor brick and roof tiles from his adobe at the former mission of San Juan Capistrano. Spanish remained the official language at the ranch, as his wife could speak no other. The ruddy-complected patron operated the ranch as a feudal barony, though his rule was paternal. The Santa Margarita ranch-house was of adobe, very thick walled, a visitor remarked. It was approached by a terrace, and had an interior court-yard. The waiting at the table was done by a broad-faced Indian woman in calico. All the domestic service was performed by those same mission Indians, except the cooking, for which a Chinaman had lately been secured, with the view of having meals on time. A white cross on a nearby hill displayed a sign of welcome: Anyone who escapes from that hospitable roof in time to keep an appointment has to be very peremptory indeed.

In the 1860s and 1870s, John (Don Juan) Forster stood as a splendid anachronism-an example to travelers, near and far, of what the life of the dons had been. He also took the first steps to diversify the productivity and income of the Santa Margarita ranch. America’s Civil War created an increased market for horses, and Forster began breeding them. On the negative side, the 1860s also brought a smallpox epidemic to the region, along with an infestation of squatters. Forster was twice arrested for what was described as killing and slaying squatters, tearing down [their] fences and playing the dickens generally. One case was dropped for lack of evidence, and the other was ruled justifiable homicide.

In the early 1870s Forster sent his agent, Max Strobel, to Europe to advertise the colonization potential of the Rancho Santa Margarita, patterned upon the Anaheim colony. Strobel also sought buyers for Santa Catalina Island, in which Forster owned a share. Strobel’s untimely death in London required Forster to sail for England. In 1873, he returned to Liverpool after a 43-year-absence and enjoyed a reunion with several of his nieces.

Forster traveled on to the Netherlands, where he sought to recruit settlers for the ranch by offering household heads 160 acres of land, five cows, two horses and sundry supplies, with rent forestalled for the first two or three years. The Dutch government ordered an inspection of the Rancho. Santa Margarita before it would approve of the plan. Forster returned to California in July 1873, unsuccessful in selling Santa Catalina Island but still hopeful for the colonization of the ranch. The inspectors arrived during the heat of August and were unimpressed. Forster’s colonization scheme failed. He then tried to establish the town of Forster City on the north coast of his property Three families settled there by 1876, and some 35 voters were registered in the village in 1882. The town, however, survived for only a few more years. Forster’s dreams of a real estate boom remained only dreams.

The potential for railroad development across the Rancho Santa Margarita also captured Forster’s imagination. In December 1880, the California Southern Railroad, in close cooperation with the Santa Fe, began laying a line from National City to San Bernardino, which would be an eventual fink with the Topeka road. North of Oceanside, the tracks turned east and followed the Santa Margarita River across Forster’s ranch. Early in 1882, from his home near the river, he could hear the sounds of track being laid. Sadly, he did not live to see the line’s completion.

John Forster died at his beloved Rancho Santa Margarita on February 20, 1882, following a long bout of erysipelas. His funeral was the largest held in southern California up to that time. Some 3,000 mourners met the train at Los Angeles. During the Mass, a small finch flew into the church and, after circling the nave several times, lit on the foot of the coffin. It then flew to the top of the organ, where it perched during the service. Following the funeral, the body of one of the last of the California dons was interred in the Pico family vault.

Don Juan Forster’s death marked the end of southern California’s pastoral era. Within three years, the rate war between the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe railroads launched southern California’s land boom of the mid-1880s. The arrival of tens of thousands of new citizens completed the Americanization of California; her Hispanic-era personalities and traditions slipped into California’s romantic past.

This article was written by Karen Holliday Tanner and John D. Tanner, Jr, and originally appeared in the December 2000 issue of Wild West.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Wild West magazine today!