[dropcap]O[/dropcap]

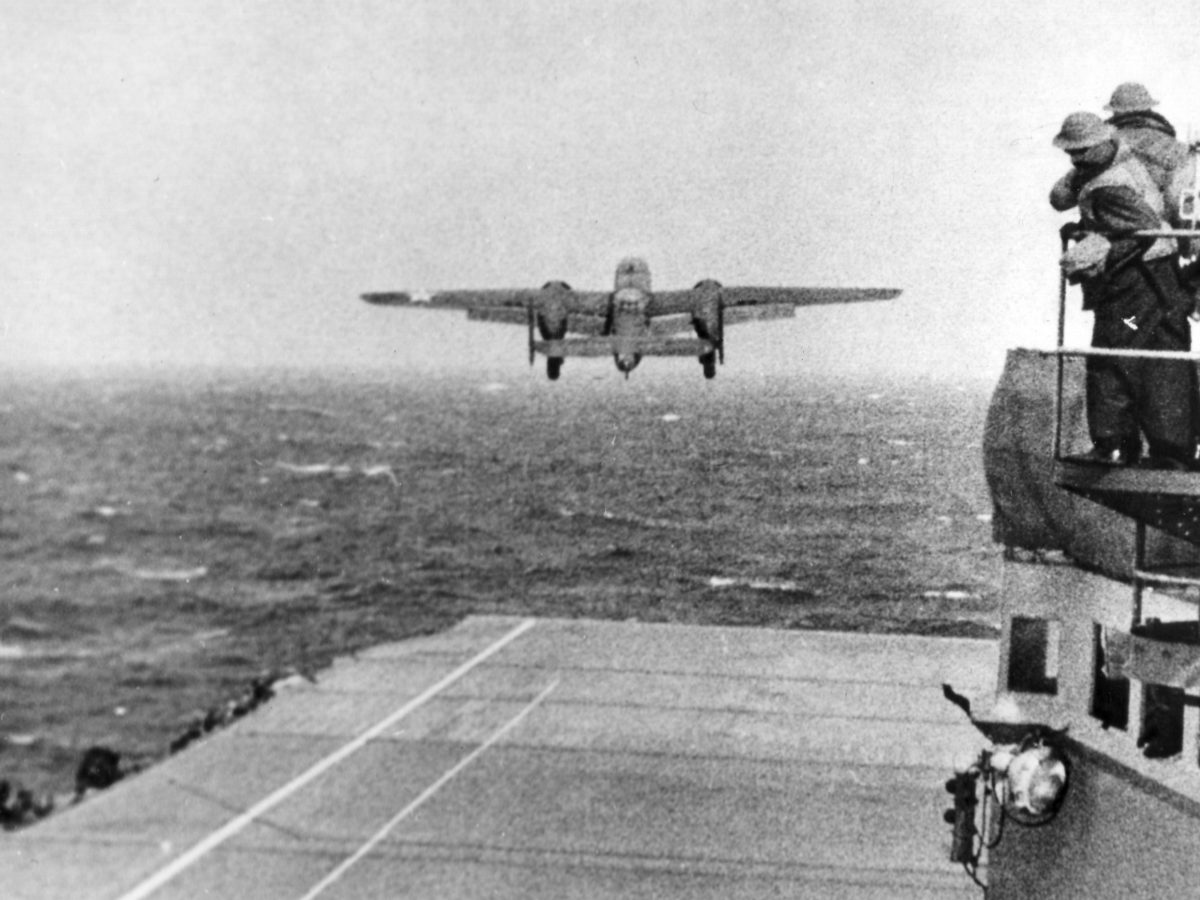

n April 18, 1942, just 19 weeks after Japan’s devastating attack on the U.S. at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, Lieutenant Colonel James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle led the famed retaliatory bombardment of the Japanese capital. Newspapers headlined the exciting news: “TOKYO BOMBED! DOOLITTLE DOOD IT!” A month later, during a brief ceremony at the White House, President Franklin D. Roosevelt presented newly promoted Brigadier General Doolittle with the Medal of Honor, awarded by Congress for conspicuous gallantry in action.

Recommended for you

Following that spectacular beginning to his World War II service, General Doolittle flew many combat missions in Europe and served as commander of the 12th Air Force in North Africa, the 15th Air Force in Italy, and the 8th Air Force in England and later on Okinawa. During his unique career in civil and military aviation, which saw him log more than 10,000 hours of flight time as pilot in command, Doolittle walked away from more plane crashes than he cared to remember; on three desperate occasions, he saved himself with last-minute parachute bailouts. Born in Alameda, California, on December, 14, 1896, the only child of Rosa and Frank Doolittle, Jimmy spent part of his childhood in Nome, Alaska, where his father was searching for gold. A somewhat strained relationship with his father and the harshness of life in the town of Nome—known as the most lawless in Alaska—instilled in young Jimmy a sense of independence and self-reliance. And the brawling that was a regular part of life in that northern frontier town resulted in his learning to defend himself at an early age.

After enduring life in Nome for eight years, Rosa insisted that Jimmy be given a chance at better educational opportunities than Alaska then offered, so in 1908, the Doolittles returned to California, settling in Los Angeles. While studying to be a mining engineer at the University of California at Berkeley, Jimmy put his pugilistic skills to good use. Despite standing only 5′ 4,” he became a West Coast champion bantamweight and middleweight boxer. For a brief time, he took up boxing professionally as a means of earning extra money.

In 1917, Doolittle joined the aviation section of the Army’s Signal Corps, where he developed a lifelong love of airplanes and flying. Five years later, Jimmy, now an Army Air Corps officer, piloted the first airplane to cross the United States in less than 24 hours. In 1925, flying a Curtiss seaplane, he won the famed Schneider Trophy race for the United States. And in that same year, he received a doctorate in aeronautical sciences at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

During the next decade, Doolittle won both the Bendix and Thompson Trophy races, set new speed and distance records, and worked to improve flying safety, becoming in the process the first pilot to fly completely “blind,” relying entirely on instruments. By the end of the 1930s, Doolittle had won almost every aviation award then in existence, a few of them twice. He had become a master of the calculated risk, but few Americans were then aware that his remarkable skills were matched by a keen, probing mind and superb executive ability.

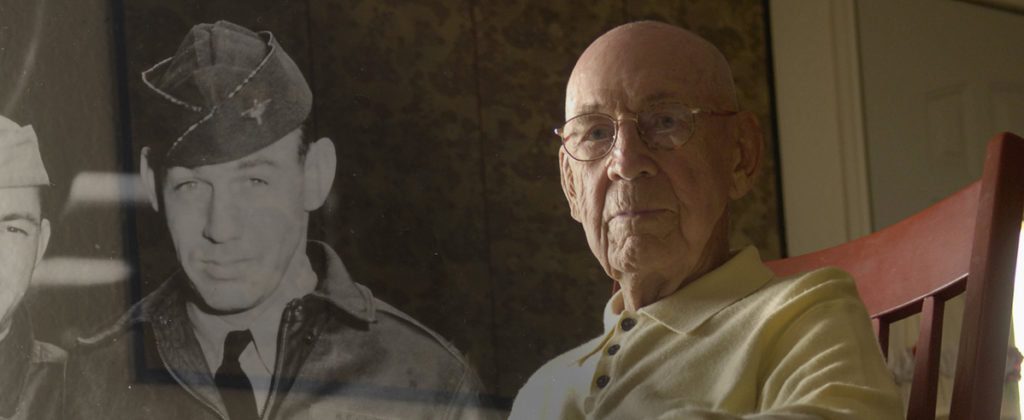

This author first met General Doolittle on November 10, 1942, two days after British and U.S. forces began landing in French North Africa. I was a Signal Corps photographic officer, sent to cover the Allied invasion, and on that day, I photographed him and his staff outside their newly established 12th Air Force Headquarters at Tafraoui Aerodrome, 12 miles south of Oran, Algeria. He spoke of that occasion, and many of his memorable experiences, when I was lucky enough to talk with him again during a 1980 interview at his home in California.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

“Early in 1942,” Doolittle recalled, “when the North African occupation was first conceived, it was planned as a very small operation. It grew, of course, into a very large British/American—and later, French—joint effort. . . . General Dwight Eisenhower had been designated to command the North African operation. In Washington, Generals George C. Marshall and Hap [Henry H.] Arnold would select the senior ground and air commanders. Marshall and [Lieutenant General Frank M.] Andrews called Georgie Patton and me to the Pentagon for a briefing before sending us to London,” where they were to report to General Eisenhower at his headquarters in the British capital. Patton had known Eisenhower since World War I, but for Doolittle, it would be their first meeting. On August 7, 1942, the two generals met with Eisenhower to review plans for the invasion.

“When Ike asked Georgie what action he proposed to take as ground commander, Georgie was all ready with a very positive, detailed invasion plan,” recalled Doolittle. When he had finished, Eisenhower nodded, obviously pleased, then turned to Doolittle. “I replied with a very stupid answer,” he remembered, telling him, “I will not be able to do anything until the air fields are captured and supplied with fuel, oil, ammunition, bombs, spare parts, and all the necessary ground personnel.” Doolittle realized that his pragmatic reply disappointed Eisenhower. “It was a dumb thing,” he said, “to tell a general with as much logistics experience and military service as Eisenhower.” Subsequently, Doolittle learned that Ike had cabled General Marshall, stating: “Patton satisfactory. I do not want Doolittle.” . . . General Marshall replied “You may have anyone you prefer. We still recommend Doolittle.” This situation “put Ike in a bad spot,” Doolittle said, “and that made him dislike me even more. Although he finally agreed to accept me, it took me almost a year to really sell myself to him.”

Despite this inauspicious beginning, Doolittle eventually became one of Eisenhower’s boys. “One thing that didn’t exactly endear me to [Eisenhower] was the fact that I had left the service in 1930,” Doolittle added. “Then when I was called back as a reserve officer in 1941 . . . he no doubt felt that somebody who had stayed in the army and been through all of the service schools would be more suitable as his air commander.”

In 1943, General Eisenhower awarded Doolittle the Distinguished Service Medal, and “the citation that came with it,” Doolittle told me, “was one of the oddest you’ll ever see. It says in substance that ‘this man has improved more during his service with me than any other senior officer in my command.'”

In 1944, Eisenhower ordered Doolittle not to fly any more combat missions because “I had been briefed on plans for the Normandy Invasion, and if I were to be captured, those plans might be compromised.” Later, when it became time for their first bombing raid on Berlin, Doolittle pointed out to General Carl Spaatz that, “having led the first American bombing attacks on both Tokyo and Rome, I would like to lead this one, too.” Spaatz agreed, but a day or two before Doolittle was to fly a P-51 ahead of the bombers, he was informed that his part in the mission had been scrubbed.

“I’m almost certain,” said Doolittle, “that General Eisenhower passed the word to General Spaatz that he didn’t want me flying over Germany.” Although Doolittle understood the logic behind the decision, he thought that “it would have been interesting for me to be able to remember that I had led the first American bombing raids on all three Axis capitals.” Doolittle described the relationship between Eisenhower and Patton. “Even General Eisenhower considered George Patton a great leader of men,” he said. “Whenever there was a difficult job to do, Ike would give the job to Georgie. [He] would do the job, and then Ike would take him out of circulation before Georgie could get himself into trouble again. Georgie was sort of like an English pit bulldog. After he’d done his fighting, you put him back in his corner.”

I had asked General Doolittle about the accuracy of the movie, Patton. He replied that “Georgie was a profound student of military history. The movie implied that he believed in reincarnation and also that he believed he had been a commander in every great battle that ever occurred. I’ve discussed those things with [Patton] at length, and that was simply not correct. Georgie did visit every historic battlefield that he could. He would put himself first in the position of one commander, then the other. Knowing from history exactly what had occurred, Georgie would then work out what had to be done. That was the only part of the movie that I thought was not quite factual.”

When Eisenhower established his headquarters on the Continent following the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944, Doolittle “was left as the senior American army officer in England” and as such reported weekly to the prime minister’s residence at 10 Downing Street. During those visits, “I became more impressed with Winston Churchill . . . than by any other man I’ve ever met,” Doolittle said. “He was absolutely unique, a great mind and a great heart.” Asked to recall other men whom he admired, Doolittle described U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall as a “man of the greatest competence and the loftiest moral ethics.” General Douglas MacArthur, commander in chief of the Allied forces in the Pacific, he said, possessed “implicit self-confidence to the extent that it could be described as egotism, but he was just as good as he believed he was.”

After World War II, Doolittle and MacArthur became involved in business together, and the two got to know each other well. Doolittle remembered MacArthur as “a great man, and I’m sure that he was also a very ambitious man. I’m certain in my own mind that when he defied President [Harry S.] Truman in 1951, he considered it necessary in order to belittle Truman and move himself a step toward the White House. That was the only thing he had left to aspire to. . . . But the little man from Missouri had both the guts and the authority to call his bluff.”

Commenting on the career of General Arnold, Doolittle allowed that he was the best commander in the field of military aviation. But Doolittle also admired another fine officer and aviator, Brigadier General William “Billy” Mitchell, with whom he had served during his first stint in the air corps. Doolittle maintained that Mitchell, who sacrificed his career to champion the cause of military aviation between the world wars, “had great vision, and his ideas were all sound, but in this world there has inevitably to be room for compromises. . . .” Doolittle added that if Mitchell “had a little less oak and a little more bamboo in him, I think he could have done even more good, because [he] was a little ahead of his time.”

As we talked that April afternoon, I asked General and Mrs. Doolittle how and where they had met. Both, they replied, had been students at Los Angeles’ Manual Arts High School in 1910. “Joe was a nice little girl,” said Jimmy. “At that time, I was an ornery little boy, and I couldn’t see any future in nice little girls.” But about three years later, he became increasingly conscious of Joe and eventually decided that this was the girl he wanted to marry. “I tried to think of any advantages she might want to consider in marrying me,” he admitted, but “actually they were hardly even measurable, but I promised that someday I’d take her on the world’s most beautiful cruise, up the Inside Passage to Alaska.”

Joe, however, was not that easily convinced and held her suitor at bay for several years. In April 1917, the United States entered World War I, and Jimmy enlisted in the Army Signal Corps. After completion of his ground school training at the University of California, he was granted a Christmas furlough before having to report for flight training as an air cadet.

That was when Joe finally agreed to become his wife. Against the advice of their mothers, the couple eloped and were married on Christmas Eve 1917. In view of an acute financial embarrassment on the groom’s part, Joe used a portion of her Christmas money to purchase their license. Then, armed with a lavish nest egg of $20 dollars, the bride and groom spent the remainder of Jim’s furlough honeymooning in San Diego. I asked the general if the fame that he achieved was as superficial and fleeting as it is popularly supposed to be. He replied that “some of the early racing and stunt flying [brought] a lot of publicity at the time [that] was not lasting. On the other hand, I believe that the work I did on blind flying, developing new cockpit apparatus, especially those instruments that permitted flying in bad weather, has been lasting.” He thought that he was also well remembered for “other pioneering procedures that I developed for testing aeroplanes . . . [which] made it possible for us to check the wing loads that were put on the aeroplane in actual flight against its original design factor.” Doolittle’s master’s thesis on that subject “wound up being translated and published in many technological journals throughout the world. I think that was a useful piece of work, and I’m sure that it has lasted.”

Doolittle gave up action flying in 1961, but curiosity eventually got the better of the general, and he “decided to check out in several of the newer service aircraft—the first supersonic fighter [the F-100]; the KC-135, which later became the Boeing 707 airliner; the B-47 [a small bomber], and the big bomber, the B-52. After that I turned in my flying suit, and I never flew as first pilot again.” Although he expected to be discontented after giving up flying, he “never missed it a speck!” What mattered the most to him in life, he added, was “Joe, my bride for over seventy years. [She] is a very extraordinary lady.”

In 1973, the couple finally made that trip to Alaska that he had promised her fifty years earlier. “It was every bit as beautiful as I’d remembered it,” Doolittle said. “[T]here has never been a time,” Doolittle told me, “when I’ve been completely satisfied with myself. . . . I’ve very much appreciated the respect that my peers have given me throughout a fairly long life. Nowadays I try to spend at least half my time continuing to be useful, still making a contribution, while getting whatever rest, recreation, and diversification I believe is essential if one is to go on living a happy and useful life.”

The general contended that the “element of luck is extremely important’ in his life, maybe comprising half the equation. But the ability to exploit that luck makes up at least the other half. Throughout my life I’ve been oh, so lucky in being at exactly the right place at the right time, without any premonition that caused me to be there.” He puts it down to “pure, dumb luck.”Especially in the case of the Tokyo raid, “. . . luck plus having the background necessary for me to take advantage of it, and being willing to work very hard to make it a success. That’s why, whenever I’m asked, I always reply that I’d never want to relive my life. I couldn’t possibly be that lucky a second time.”

This article was written by William R. Wilson and originally published in the August 1997 issue of American History Magazine. For more great articles, subscribe to American History magazine today!

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.