A Rising Star Struck Down in His Prime

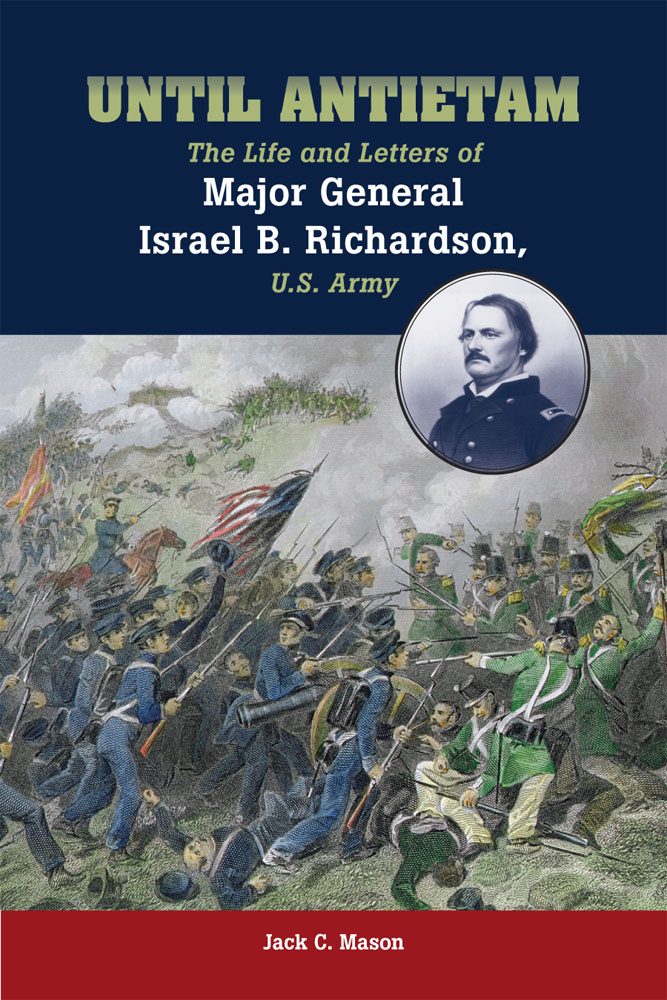

Until Antietam: The Life and Letters of Major General Israel B. Richardson, U.S. Army, by Jack C. Mason, Southern Illinois University Press

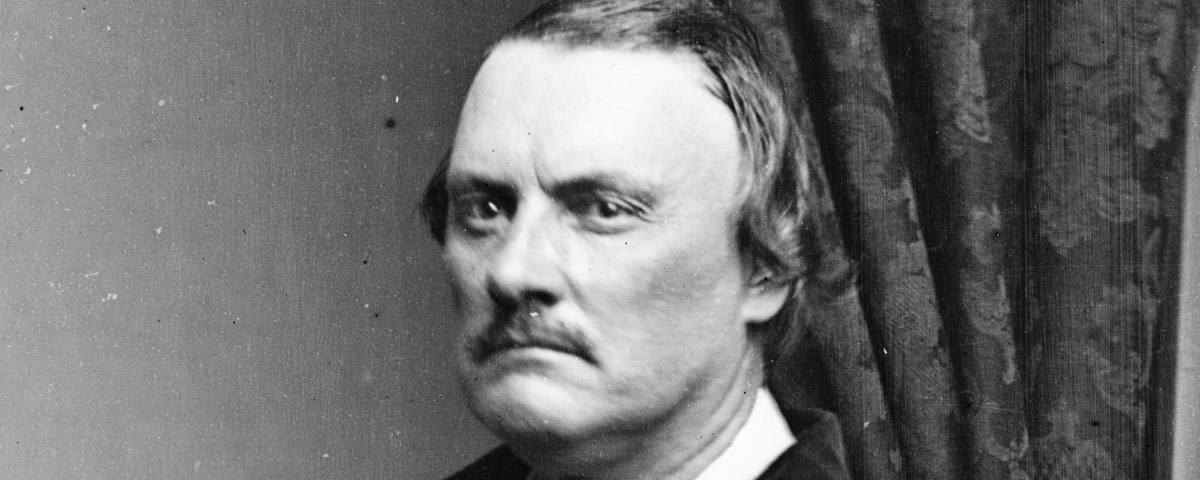

Up to the moment he was mortally wounded along Antietam’s Sunken Road on September 17, 1862, Israel Richardson had been a rare bright spot in the Union Army’s dysfunctional early-war command fraternity. For some reason, though, the Vermont native tends to be overlooked in many accounts of the Battle of Antietam as well as larger Civil War histories. Fortunately, with his impressive new biography, Jack Mason rescues Richardson from slipping further into historical obscurity.

“Fighting Dick,” a captain in the antebellum Army before resigning in 1855, rose quickly through the volunteer ranks early in the war and was elevated to divisional command in Edwin Sumner’s II Corps at the outset of the Peninsula Campaign in May 1862. Although he was known as a rigid disciplinarian, the unpretentious Richardson cared deeply for his men and was fearless in battle. He quickly molded arguably the finest and hardest-fighting division in the whole Army of the Potomac.

To tell Richardson’s story, Mason relied heavily on the general’s own writings, including about 100 previously unknown letters that Richardson had penned to his family during 20 years of service. This correspondence shows the personal side of a man usually characterized as mostly a gruff and aggressive warrior.

Mason contends that, had he survived, Richardson would have risen to corps command, which is hard to refute considering both of his fellow II Corps divisional commanders at Antietam—John Sedgwick and William French—were ultimately promoted to that level. Mason’s argument that Richardson was being seriously considered as George B. McClellan’s replacement to lead the Army of the Potomac is debatable, however. According to Mason, Abraham Lincoln made an overture to that effect while visiting the wounded general at the Pry House, but he relies on the postwar writings of Captain Charles Draper, one of Richardson’s aides, in making this claim. While Richardson fit the mold of the “fighting general” that Lincoln admired and it was popularly believed his appointment to army command would assuage the Radicals in Congress, no other sources are presented to support Draper’s account—and the aide’s own motives and veracity go unquestioned by Mason.

Although there are minor historical errors in his book, Mason has done a valuable service in bringing Richardson’s fascinating story to life.