The ‘unexpected’ Rebels he met at Bull Run weren’t unexpected at all

The ‘unexpected’ Rebels he met at Bull Run weren’t unexpected at all

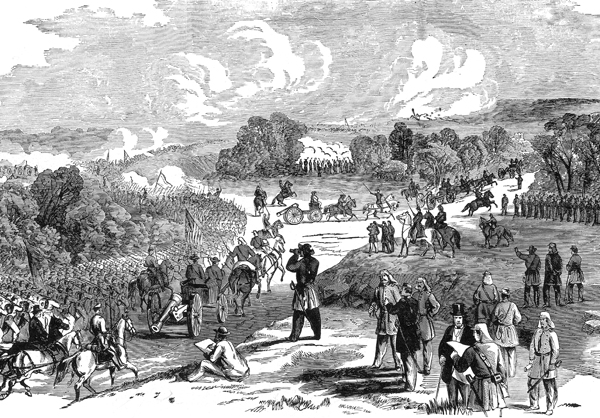

In the early summer of 1861, few people North or South believed the Confederate David would be much of a challenge against the Yankee Goliath. When the two sides finally squared off in a full-scale battle on July 21 at Manassas, Va., that presumption of Union “might” held true—for a while. Despite bumbling by some units at the outset, Irvin McDowell’s Army of Northeastern Virginia was on the verge of a major victory by early afternoon. But after the timely arrival of reinforcements and a determined stand on Henry Hill by, among others, Thomas J. Jackson’s Virginians, the Confederates turned sure defeat into triumph. As twilight approached, most of McDowell’s men were fleeing toward Washington. The Rebel victory at First Manassas—the largest battle yet fought on the North American continent—resulted in 2,950 Union and 1,750 Confederate casualties. It also put an end to the widespread notion that the war might be a short one.

The calendar said December 26, 1861. But in a meeting room at the Capitol in Washington, Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell was, at the behest of the U.S. Congress’ Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, reliving the heat of July 21. Somebody was accountable for the Federal disaster at the First Battle of Bull Run, and McDowell was determined that, for the moment at least, it wouldn’t be him.

In his testimony—he was one of dozens called to answer questions regarding the Army of Northeastern Virginia’s conduct at Bull Run, known to Confederates as First Manassas—McDowell summarized the main reason for the failure of his army in the Civil War’s first major battle:

All I did expect was that General [Benjamin] Butler would keep [the Confederate forces] engaged at Fortress Monroe, and [Maj. Gen. Robert] Patterson would keep them engaged in the [Shenandoah] valley….That was the condition they accepted from me to go out and do this work. I hold that I more than fulfilled my part of the compact because I was victorious against Beauregard and 8,000 of Johnston’s troops also. Up to 3 o’clock in the afternoon I had done all and more than all that I had promised or agreed to do; and it was this last straw that broke the camel’s back—if you can call 4,000 men a straw, who came upon me from behind fresh from the cars.

McDowell denied responsibility for his humiliating rout by the combined armies of Generals Joseph E. Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard. In his view, he had “contracted” with his superiors to fight only Beauregard, not Johnston, who had arrived with reinforcements while McDowell was marching to Manassas, a vital rail junction about 25 miles from Washington. The committee ultimately agreed with the Union commander, concluding in its report that “the principal cause of the defeat on that day was the failure of General Patterson to hold the forces of Johnston in the valley of the Shenandoah.”

By and large, historians have accepted McDowell’s argument, at least in part, and the story of the Union falling victim to “unexpected” reinforcements at First Bull Run has been passed down ever since. Analysts of the campaign also point to various delays in McDowell’s march from Washington—and more delays on the day of the battle—as significant factors in the Union defeat.

But did the success of the Union movement against Manassas really “depend,” as McDowell claimed, on Patterson keeping Johnston in check back in the Shenandoah Valley? The answer lies in McDowell’s expectations, expressed clearly in his plan of operations.

In June 1861, President Abraham Lincoln directed McDowell, who had been named commander of the Department of Northeastern Virginia in late May, to launch an offensive against Beauregard’s Army of the Potomac stationed at Manassas. McDowell’s inexperienced troops probably weren’t yet ready for a major battle, but Lincoln was concerned that the three-month terms of service of thousands who had volunteered after Fort Sumter would soon expire—with a large Confederate army still poised close to the nation’s capital.

McDowell responded with a general plan that he presented June 29 to Lincoln, members of his Cabinet, General in Chief Winfield Scott and other officers. While acknowledging his army largely consisted of raw regiments inexperienced with campaigning, McDowell seemed confident he would succeed. He never proposed making an outright frontal attack on Beauregard’s army, which occupied an eight-mile front along a stream known as Bull Run that straddled the border of Prince William and Fairfax counties.

The Rebel defenses stretched on the left from where the Stone Bridge crossed Bull Run at the Warrenton Turnpike, to Union Mills Ford on the right—along with a contingent at Fairfax Court House a few miles to the east. McDowell decided a turning movement against the Confederate right was his best course. He hoped to cut off the Rebels’ rail link to the south or to force them to leave their defenses to protect their line of communications.

McDowell estimated the Confederates’ strength at 25,000 men, but assumed that once his army set off for Manassas, Beauregard would quickly learn of his approach and respond accordingly. Even if Patterson managed to hold Joe Johnston’s army in the Valley, Beauregard would undoubtedly have time to gather another 10,000 reinforcements, giving him a total of 35,000 troops. McDowell planned to conduct his operation with a force of 30,000 men, with another 10,000 in reserve.

McDowell estimated the Confederates’ strength at 25,000 men, but assumed that once his army set off for Manassas, Beauregard would quickly learn of his approach and respond accordingly. Even if Patterson managed to hold Joe Johnston’s army in the Valley, Beauregard would undoubtedly have time to gather another 10,000 reinforcements, giving him a total of 35,000 troops. McDowell planned to conduct his operation with a force of 30,000 men, with another 10,000 in reserve.

With the exception of the eventual size of his reserve force—5,000 men instead of 10,000—these basics would remain as the campaign evolved. McDowell would attempt his turning movement, drawing on a force of 30,000 green troops against a defensive position manned by an enemy army assumed to exceed his own by 5,000.

While on the face it seemed a bold plan, it was not an unfamiliar one. In fact, it embodied Winfield Scott’s famed campaign 14 years earlier in the Mexican War. McDowell anticipated that he could fine-tune his plans on the march as he learned more about the lay of the land between Washington and Manassas.

On July 16, McDowell issued orders for the march to Manassas. He had organized his army of roughly 35,000 men and 55 artillery pieces into five divisions—the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 5th, with the 4th, under Brig. Gen. Theodore Runyon, in reserve. The general assigned march routes to the divisions, identified where he assumed the enemy would be, and instructed his men to travel light and with extreme caution. Setting out that morning, McDowell still didn’t have enough intelligence of the Rebel army’s position or the topography of the area to issue more specific orders.

Although McDowell had emphasized that the move to Centreville might be slow and methodical, it was delayed even further because he didn’t efficiently employ his small cavalry force to scout the advance. After proceeding to Centreville and personally reconnoitering the Confederate right on July 18, McDowell decided a turning movement in that direction would not work.

The next day his engineers scouted the Rebel left, near the Stone Bridge. They made five forays by July 20, but without success: There were so many Rebel pickets on the Fairfax side of Bull Run, McDowell’s engineers couldn’t get close enough to the stream without being detected. McDowell intended to get the required information—a route to and crossing points above the enemy’s left—by a reconnaissance in force that day, but his subordinates persuaded him against it. That evening McDowell issued orders for the advance the next day, based on the little information already gathered.

Two divisions—the 1st under Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler and the 5th under Colonel Dixon Miles—were given primarily diversionary roles. Tyler’s men were to leave Centreville at 2:30 a.m. and proceed along the Warrenton Turnpike to the Stone Bridge. On the assumption that the Confederates had mined the bridge and obstructed the road, Tyler was instructed to merely threaten their position, opening fire at “full daybreak.” Miles would meanwhile threaten Blackburn’s Ford, just off the Manassas-Centreville Road.

Colonel David Hunter’s 2nd Division, followed by Colonel Samuel Heintzelman’s 3rd, would move down the Warrenton Turnpike behind Tyler and then turn north after they crossed Cub Run. According to McDowell’s written plans, Hunter was to “pass the Bull Run stream above the lower ford at Sudley Springs, and then, turning down to the left descend the stream and clear away the enemy who may be guarding the lower ford and bridge. It will then bear off to the right, to make room for the succeeding division.”

Following Hunter, Heintzelman would turn west at Poplar Ford, which crossed Bull Run in the direction of Matthews Hill, “then, going to the left, take [a] place between the stream and [the] Second Division.” The two divisions would then clear the turnpike from left to right, in order “to turn the [Rebel] position, force the enemy from the road, that it may be reopened, and, if possible, destroy the railroad leading from Manassas to the valley of Virginia, where the enemy has a large force.” Although McDowell did not identify that railroad, it was likely the Manassas Gap Railroad at Gainesville to the west, which would have been accessible via a move around the enemy’s left.

Hours before dawn on July 21, McDowell set in motion the final phase of his plans for the battle, which would pit the two largest armies yet assembled on the North American continent against each other.

How reasonable were McDowell’s expectations, and how nearly were they met? Did circumstances beyond his control nullify his assumptions?

Delays continued in the early hours of July 21. Tyler’s move from Centreville to the Stone Bridge was dogged by slow, cautious marching; the failure to reinforce the bridge at Cub Run to allow artillery to pass slowed him even further. But the time needed for his long column to clear a point from head to tail was perhaps estimated too optimistically.

A local guide amended Hunter’s route to Sudley Springs on the fly, resulting in a longer march. The same guide was also unable to find the road to Poplar Ford, which Heintzelman was to cross to join with Hunter as he moved south; consequently, Heintzelman simply followed Hunter north to Sudley Springs. These delays gave the Confederates time to discover the Federals’ movements and counteract them by shifting troops from other areas of their line. But despite the delays, McDowell’s men fought their way through three Confederate brigades on Matthews Hill and consolidated along the Warrenton Turnpike. By early afternoon, the Federals seemed in good shape to drive the enemy from its defenses south of the turnpike.

Various factors conspired to turn the tide in the Rebels’ favor. After another delay of about an hour to establish his lines, McDowell moved across the turnpike toward the Confederate position on Henry Hill. But the regiments in the newly formed brigades were unfamiliar with each other—division commanders couldn’t coordinate attacks by multiple brigades, and brigade commanders inserted regiments piecemeal into the fight. McDowell neutralized his own advantage in rifled- and larger-caliber artillery when he advanced the batteries of Captains Charles Griffin and James Ricketts to within close range of the mostly smoothbore and smaller-caliber Confederate guns, making them unnecessarily vulnerable. Meanwhile the Rebels coordinated counterattacks with multiple units.

Perhaps most important, the Yankees didn’t have enough troops to overcome the Confederates’ advantage defending the higher ground at this critical juncture. While the Federals were marching toward Manassas a few days earlier, Johnston’s Army of the Shenandoah had slipped around Patterson’s 18,000-man Union army near Winchester. Moving primarily by rail, a sizable portion of Johnston’s army arrived at Manassas by mid-day July 20. More troops under Wade Hampton and Theophilus Holmes had also reached the field by that time. Finally, on the morning of July 21, another of Johnston’s brigades under Edmund Kirby Smith debarked at Manassas Junction. By mid-afternoon, 1,700 of those men had reached the battlefield just in time to help repel the final Federal assault of the day by Colonel Oliver O. Howard’s brigade on Chinn Ridge. That final setback spurred a general retreat all along the Union lines.

The rout was on.

At first glance McDowell’s claim that Johnston’s arrival alone foiled his plans and violated the terms of his “compact” appears reasonable. Johnston’s army clearly played a decisive role in the outcome, since it constituted more than half of the 18,000 Confederates engaged west of Bull Run. On that day and into 1862, it is likely McDowell truly believed he had faced much longer odds than anticipated.

But in fact the reinforcements that flooded into northern Virginia after the Federals marched from Washington formed a combined force of no more than 35,000 men—precisely the number McDowell had predicted at the end of June 1861, a prediction he apparently never amended. By mid-1862, published Confederate reports revealed the true state of affairs.

Yet the impression that McDowell anticipated fighting an army smaller than the one he met, that he expected to outnumber his opponent, remains.

In truth, his estimate of the size of the Rebel army he would face around Manassas was McDowell’s most accurate assumption of all.

Harry Smeltzer hosts the blog Bull Runnings and is a regular book reviewer for America’s Civil War.

Article originally appeared in America’s Civil War, July 2011