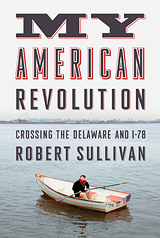

Robert Sullivan’s new book My American Revolution: Crossing the Delaware and I-78 is an illuminating, idiosyncratic and intensely personal answer to the historian’s eternal question, How can I connect with the past? In Sullivan’s case he sought to connect with the American Revolution, as it played out in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, and especially in the great estuaries of the Hudson and Delaware rivers. His quest centered on being there—standing, hiking, camping, rowing precisely where something historic happened—and then obsessively researching the circumstances of the events and the key players. In short, it became a matter of reflecting deeply on the place and times. Sullivan’s result is part memoir, part travelogue, part research monograph, part adventure yarn, part staff ride and part interview. At once Thoreauvian, picaresque, wise and deadpan comedic, it is—for anyone pondering the ties of present and past––a model of its kind.

‘You can read about a place. You can look at it on a map. But when you are standing in a place, that’s the only way to know it’

How would you describe the focus of your new book?

It’s about how you find history in places, about looking for history in hills and streams and old streets. It’s about the so-called footnotes of history, about characters who failed and lost but maybe contributed in a larger sense. The book is also an almanac, trying to lay out the history of the American Revolution in the place where, I argue, it was mostly fought and probably mostly lost or not won—in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut.

How did you conceive of the book?

I grew up partly in New York, went to high school in New Jersey and worked at a newspaper in New Jersey. Ever since I was a kid, and especially when I was a newspaper reporter, I’d look out and wonder, How did they get down to the Delaware River from Fort Lee? Where did they cross? So my book is a many-decade answer to those tiny questions from long ago.

I started figuring out a way to write it three years ago and about two years ago started writing it.

Why write about the Revolutionary War?

Because that’s the starting point in the “American landscape” and the oldest thing you hear about if you grow up here. But you don’t hear much about it. I’d grown up with WPA murals in school that showed George Washington, but through my whole life nobody could tell me what Washington did here.

Then, suddenly, I was a father, and I took my own kid to places when he was a little boy, and I’d say, “Look, George Washington was here,” and he would have questions.

You’ve mentioned a plan of attack to the book. What was that?

It was two-fold.

One was: OK, you’re going to write about this area, and you’re going to stand up on top of the Empire State Building, and you’re going to look out at the whole region. Now are you going to take people through this? How are you going to think about this? So I had to have a plan of attack as a storyteller.

Second, I drew a map when I set out to write this book. I looked at the map and asked: OK, what are the themes in this landscape? Obviously, there are these hills, and there is this river and this harbor. So how am I going to talk about each of these landforms in this book? I looked at stories in the past that somehow aligned with each of these landforms.

What did you expect to find at these Revolutionary War sites?

I expected to find nothing, all traces of the past gone. So I was almost always either pleasantly surprised––or startled. In some cases you just gasp at how clearly the strategy of the landscape presents itself. And sometimes I’d go in looking for one thing and find something else.

Did maps play an important role in your research?

Having a good map before you set off to do anything is important. It was important in the past, and it remains important now. Thinking about maps and the past is interesting as an analysis of history, but it’s also deeply metaphorical. It applies to how we think about our own pasts. A sense of where you are at any given moment relates to where you’ve been.

In the book you refer to an “epiphany of a place.” What does that entail?

You can read about a place. You can look at it on a map. But when you are standing in a place, that’s the only way to know it. When you get there––and if you have researched it deeply––the character of the site becomes tremendously important.

What is the essential importance of place in seeking to understand a pivotal event like the American Revolution?

You can discover the strategy of the landscape by looking back at these old battles and at these old retreats and evacuations. You discover they align with an even deeper path. Old roads the Continental Army used were Leni-Lenape Indian trails. The strategy of a landscape does not change; geology and earth forces are bigger players in our lives than we oftentimes realize. That is the strategy of the landscape. You discover it, and you also discover its resilience.

Which of the battle sites you visited surprised you the most?

The Delaware crossing is really impressive, because the centerpiece of it is the river. A river is the past going into the future through the present. The Delaware is yesterday’s rain in the Catskills and tomorrow’s Atlantic Ocean.

What’s great about the Delaware crossing is there’s all this other stuff around it that may or may not have changed. There are plaques and rocks, and surely the banks have changed and the depth of the river has changed because of sand and silt. But the river itself is the same—and it’s never the same.

Why spend so much time exploring on waters?

The key to this landscape is the Hudson estuary, this giant estuary. It goes up to the highlands. It goes down into Jersey and toward Pennsylvania, into Connecticut. You think about giant cities around the world that have settled on estuaries, and you think about the importance of estuaries to human settlement.

What was the greatest discovery you made while researching the book?

My big discovery is that people are constantly discovering the history of the Revolution in places where nobody would imagine they’d be rediscovering it. And they are using these discoveries to move forward.

What’s your view of battle reenactors?

I’m not a reenactor, although I wouldn’t mind being one. I didn’t have the budget for clothing and so forth. But I was interested in how reenactments started, and when they started and where they come from. Thinking about reenactments takes you a long way back.

They’re working on the same project I am—how you connect with the past. That’s the way they do it. I’m doing what I call “re-emplacements,” going to the place where something happened in that season, in that time of year—more of an outdoor adventure angle.

Why do New Jersey’s Watchung Mountains figure so prominently in your book?

They were key to George Washington’s strategy about the Revolutionary War, his strategy being, OK, we can’t beat them on a field, army vs. army, so we’re going to use these mountains to come out and fight, and go back and not fight. If you look at how geology relates to a war, these turn out to be the most important little group of mountains in the history of the Revolution. Yet, they are completely invisible to anyone who lives here. They think of individual hills, not necessarily a mountain chain.

And they figured in one of your “re-emplacements”?

It turns out Washington commanded Lord Sterling [William Alexander] to build giant pyres that would be lit if there was troop movement by the British. So in 1777 one might have seen fires all along the mountaintops. It’s very Tolkien.

I thought, OK, can I reenact this? First I thought, OK, can I build a fire on top? No. I’ll get arrested. Then I thought I’d signal back to New York. If anybody could see me, I would be recreating that same sight line.

My wife bought me a Boy Scout reflection mirror. I started going up those mountains on the weekends and trying to signal back to my wife [in Brooklyn]. Then I tried to get my landlord involved. He got up on our roof, and I signaled back to him. Nobody could see me.

In the end we went to [my daughter’s school], St. Ann’s, in downtown Brooklyn, went about 10 floors up and looked back at the Watchungs. From there you could see a hill in that little gap, near the Springfield gap. I went up and signaled back, and I could hear the shouting on the cell phone. The whole class––everybody in that room––was cheering and could see the signal. Of course, I can’t see a thing. That’s kind of beautiful in itself. To me that kind of symbolizes how we live in history. We make little marks, and then we go away, and we can’t see how what we do in life is communicated or transmitted.

What else did you discover?

When I was trying to find these spots, and when I stood where I stood, I was very near plaques that pointed out Washington signaled here or stood here or positioned troops here, and I could see the city. I was also near missile sites set up in the 1950s to target Soviet bombers. So, the strategy of the landscape remained, almost to a site. Almost all of those places also had become memorials to 9/11, because people had gone there and stood together to look at the Twin Towers burning. It all lined up.