I approach everything like it’s the next battle….

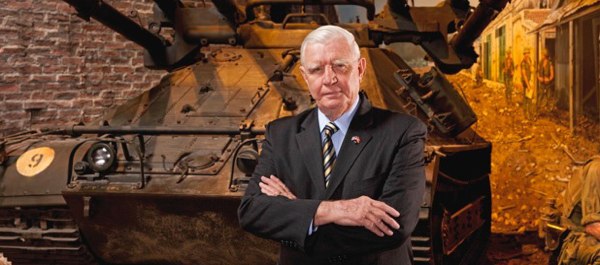

From the day he arrived at Quantico half a century ago, to the day in 1968 when he was seriously wounded at Hue City, and to the day he hands the keys to the Marine Corps National Museum at Quantico to the secretary of the Navy this December, Ron Christmas has lived and breathed Marine. Awarded the Navy Cross for his valor in Vietnam, Christmas officially retired from active duty in 1996, but his service to the Marine Corps was far from over. Indeed, in the past 16 years, Christmas has applied the same intellect, determination, intestinal fortitude and devotion to his comrades that made him a great military leader to the task of envisioning and bringing to fruition a stellar museum that pays homage to the Marine legacy from 1775 to 2011. As Christmas stands down as president and CEO of the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, a major expansion of the museum is set to begin. We recently spoke with Lt. Gen. Christmas at his beloved museum about his experience in Vietnam and his life as a Marine.

Did you always want to be a Marine?

I was born in Philadelphia in 1940 to hard-working blue collar parents. Dad got to the sixth grade and mother to the eighth. I had a wonderful childhood and got a scholarship to the University of Pennsylvania. Based on my background, I was probably their first “diversity” student. I had no military background as my dad had been too old for WWII, but there was a draft back then and I realized the smart thing to do was to join the NROTC and I would get my draft requirement done. Besides, I would also get 25 bucks a month, and boy, would that help. At Penn I was very impressed by the Marine professors I had there. I found the Marines were just my kind of folks so I got a Marine contract in 1962, came to Basic School and became an infantry officer.

How did you decide to make it a career?

The Cuban crisis was going on then and I went to Camp Lejuene and picked up my first infantry platoon and went off to the Caribbean. I came back and it I was pushing my second year, when my platoon was slated to go back to the Caribbean to be the only ready force with the Navy ships. I thought, they can’t go to the Caribbean without me, obviously, so I extended for another year. Sure enough, as we are tied up down in San Juan, I’m looking at this big sun setting down in the emerald sea and say to myself, “Who the hell are you kidding, you love this stuff.” So I requested a regular commission, and the rest is history.

When did you go to Vietnam?

I was married in 1965 and was stationed at Marine Barracks in Washington. I was promoted to captain in 1966, then went into Vietnam 1967. I walked in the wrong day, they made me the commanding officer of the Service Company, Headquarters Battalion, which has all the cats and dogs, the disbursery and you name it. Right away, I realized these guys didn’t feel like they were part of the war, so the first thing we were going to do, as we were in a combat zone after all, we were going to ensure our defensive position is in order. “Disbursery sergeant,” I said, “you’ve learned to be a rifleman, so you’re going to patrol.” Later, during Tet, after I was gone, that proved very beneficial to them.

But before long, you were in the bush?

In late 1967 I shipped out to 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines south and west of Da Nang, where I was named commanding officer of Hotel Company. I can remember how that very first night I walked the company lines and I was appalled that I had Marines with battle sight zero and Claymores turned the wrong way. I put into practice what has been a basic premise I’ve always taught, that you never stop training. So we were not only in a combat operation, but we were in training, and we got the company in pretty good shape.

Where were you in the lead up to Tet?

In late November 1967, Gen. [William] Westmoreland ordered Operation Checkers to reinforce the areas around Khe Sanh and move all Marine forces north. He was concerned that we were going to see division-size enemy forces coming down. At the same time, Ho [Chi Minh] and [Vo Nguyen] Giap realized the war not going their way and decided on the Tet Offensive.

How did find yourself at Hue during Tet?

We were at Phu Bai and then were ordered to take a convoy in to relieve the MACV compound at Hue. We called it the convoy to hell. We had two Army Dusters, they were my tanks, one in front and one in back. We literally rehearsed how we would react to an ambush. I wanted nobody except drivers in the cabs. Unfortunately, a young lieutenant from another outfit wanted a ride up and decided he would do what he wanted and hopped in the cab of the second truck. About five blocks from the MACV compound, they took the second truck out with an RPG and he was our only KIA on the convoy.

What was the situation when you got there?

The compound reminded me of an old fort surrounded by Indians. This was not in the Citidel, but in the southern part of Hue, like old Boston, where the university and hospitals were. Hotel Company was ordered to take the nearby university. I really believe the NVA thought the ARVN, not Americans, would race up in a column of APCs toward the capitol and jail. See, they were in strong points on the way and would have let them go by, and it then would be a killing zone against the Perfume River. But, we would go at it house to house, eyeball to eyeball with the enemy.

Were you prepared for urban combat like that?

None of my men had really been trained in urban combat. Its really funny, when you’re out in the boonies the kid from the country were very comfortable, you know, but in the city, my men from Harlem and South Philly, they really stood up. But they all adapted amazingly well and did an unbelievable job. So we took that portion of the city and had it cleared fully by February 11. There was only one bridge left to get the forces up to the Citadel. Others hadn’t been able to make it, so we were ordered to get across and hold the bridgehead. It was an unbelievable night, and you could tell how well it was defended. We decided we had to get across all at once, call it a rush, so we just fired for effect about 28 rounds of 82mm, followed by about 14 white phosphorus rounds and then literally ran the whole company across at once. We drove them off and that night we held the adjacent railroad track against pressure from a battalion-size organization. Seeing that we held, we were ordered to push out—a company trying to push against two battalions. We lost three kids trying to do that before we were ordered to withdraw. Well, we weren’t going anywhere until got our three Marines, and we did. Now, the only way to get back across the bridge was the same way you came across, running all at once. We all ran across that bridge, the first time we had ever withdrawn, running in the face of the enemy. It was psychologically damaging to the kids.

How did your company respond after that?

They put us in reserve for the first time. We had a Catholic chaplain who found a bombed out chapel and wanted to give a memorial mass for our seven dead. I said OK, but it would have to be voluntary. When I walked in the chapel, every Marine in the company, except those on watch, was there. That chaplain did an amazing thing, what we needed. He invited every Marine to take communion, and they all did. They had honored their brothers, said goodbye, closed the action, and moved on.

And two days later, how did your combat career come to a sudden end?

On February 13, we literally overran an NVA headquarters and they started to mortar us right away. As I called in our platoon commanders to give instructions, I looked over and saw an NVA soldier come up from behind an obelisk and he has an RPG aimed at me. It goes “boom,” and as I’m watching, I’m thinking, why is he shooting that at me? I’m not a tank! That’s how I got wounded. Two Marines pulled me aside and tried to control the bleeding as more mortars are coming in. They dove on top of me to protect me. Those men are very special and will always be. That’s who Marines are. And that’s what this museum is all about. It belongs to them. Any Marine who comes here, they know that, they embrace it. That’s why it’s so important to finish the job for the kids today.

What do you say to Vietnam vets who are hesitant to visit the museum?

I say to them, it will be uplifting. When you come here, you realize your important place in the history of this nation, that you count, that you and what you did is important. Yeah, maybe you’ll have a flashback or something, but this is yours.

Does the Hue exhibit here affect you?

No, I came to closure a long time ago.

How does this museum compare to The Wall for Vietnam vets?

I will tell you I didn’t go to The Wall for a long time. You know, you keep the young men you lost inside you. But one very late night after a Marine ball in Washington, my wife said. “Let’s go.” I did my closure, and I haven’t been back. The difference is that those you’ve lost are somehow still living here. At that wall, they are gone. For me, here they are alive—sometimes literally. During the time Hotel Company took the southern part of the Hue, I had two sniper teams, shooting at the NVA regiment. They got two, got four, got up to 14 kills. I knew better. I should have moved them. Well they got hit with a mortar round. I always thought I’d lost them all. Then one day, at this museum, one of those snipers walked up to me. That’s what this place is all about.

It must be gratifying to know that you are giving veterans a place to find pride and closure.

I’ve been at it almost 16 years and did it pro bono for about 10 years. We’ve completed phase one, and this November we will make our very last payment on our construction loan and will be ready to start the next phase. It is wonderfully satisfying, because you know that every day someone comes here and finds closure. Whether it’s at the Iwo Jima exhibit, the Chosin Reservoir exhibit or the Khe Sanh exhibit, you’ll see vets who may have never talked about their experiences, and you see some of them break down. And then, at the same time, you see all the young, new Marine Corps officers coming through, learning about the legacy that they will be building upon. To earn the title Marine, whether at boot camp, Parris Island, San Diego or officer training, you learn the history and you understand you can’t let that legacy down.

There was a strategic vision applied to creating this museum, wasn’t there?

At the beginning, we were determined the museum would be first-class all the way, not some old Quonset huts. And we decided that the first galleries would be World War II, Korea and Vietnam, so the veterans of those wars would have the opportunity to see them. We then move forward building out the World War I gallery. In the first phase build out, our history ends in 1975. The next phase will pick up Marine Corps history at 1975 and ensure we honor young men and women who have served since Vietnam. And we don’t want to wait 40 years, we are going to make sure it is done now.

The first thing we will begin with next year is the building of another entrance that will enable two things. First, visitors will have a more scenic entrance to the museum, that goes right by chapel and offer an overlook and the second thing is that for the next four to five years we will be using the existing entrance for the construction vehicles. There will be another 80,000 square feet that will become museum.

And, even in a decade, the expectations of the public have changed, haven’t they?

Good museums do change and update their exhibits, and we are no exception. We are interactive and experiential. The next phase will include a multipurpose 350-seat theater that will show widescreen digital, 3-D films. A 30 to 40-minute film, which I’ll be helping with, will put visitors into the boots of a Marine. So when they start out they’ll be fired up to run through the galleries. Or run to the recruiting sergeant that will be standing outside waiting for them to enlist. The new galleries that will be on the bottom level will go right up to the present and there will be a changing gallery, which is critical because you can never cover all the history in the permanent exhibits. On the second deck, there will be classrooms, a sports hall of fame and a full art gallery displaying some of the Marine Corps’ unbelievable art collection, and a working studio so visitors can see the Marine combat artists actually doing their work.

We are also moving forward with our plans for an adjacent hotel and conference center. The Department of the Navy leases the land to the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation and we then sublease to the developer.

World-class museum, chapel, hotel, conference center. Did you ever imagine you’d see this come to fruition?

I think it’s all about vision. Back in 1994, Congress passed a law that said each armed service could have a national museum. Then, the Marines had a little historical society. We said we wanted a truly national museum. After retiring from the Marine Corps in 1996, I was deployed for the next decade as senior mentor to the Marine Corps and Joint Forces. I then made the mistake of going to breakfast with a former commandant of the Marine Corps and walked out as volunteered president of the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation. They had had the wisdom to change the name from Historical Foundation to Heritage, thus broadening its perspective. It’s been a labor of love.

So, how do you get from there, to here?

If you have a dream you have to create a vision, and after you create a vision you have to determine whether you can really carry it out. So, between 1997 and 1999, we did our studies and in early 1999 made the decision: we were crossing the line of departure. Once we decided to do that, there was never any turning back. At first we didn’t realize the overwhelming support we would receive from the American people. Our original fund-raising goal was to reach $25 million by time the first phase was to begin. We actually brought in about $89 million. Once we had decided on this design and once we had the 135 acres of this wonderful park, you could envision what could be accomplished.

Then, in 2001, we were able to have a law enacted that allowed the Marine Corps and the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation to go into a public/private partnership in which the Foundation would construct the building and develop the grounds and the Marine Corps would operate and maintain it. It has worked exceptionally well, allowing the foundation to do the fundraising. And, this will all be gifted to the Navy when we pay off the final note this year. Now we are embarked on a $105 million fundraising campaign for the next phase and have raised $58 million to date. When we reach our goal, all of the rest of the museum gets completed.

We have had over 2.5 million visitors since we opened our doors, about 500,000 a year. Once we have the new theater, we may increase that annual visitation by another 250,000. We are really trying to get the word out.

And the chapel has become quite a hit too?

We’ve been accused of running a Las Vegas-style wedding chapel. Our record is six weddings on one day! And, we are so close to the Marine Corps National Cemetery.

How does the museum help educate vets and non-vets alike?

What’s been created here does not glorify war. But it does tell Americans that if you send your sons and daughter to war, this is war. You need to understand that.

How do you account for the rapid realization of the museum, and now its big expansion?

I approach everything like it’s the next battle: You have to have a strategy, you have to remember the operationals and you do the tactics it will take to make it happen—and you have to remember that once you cross the line of departure, you never turn back. You may have to do a frontal attack, you may have to do an envelopment and you may have to infiltrate sometimes. I think it’s all about vision, and at the Foundation and the museum, I have had outstanding people to work with. It started out as a very small team—used to be my fire team—but I think we are a platoon now. And, you know what? You ain’t seen nothin’ yet!