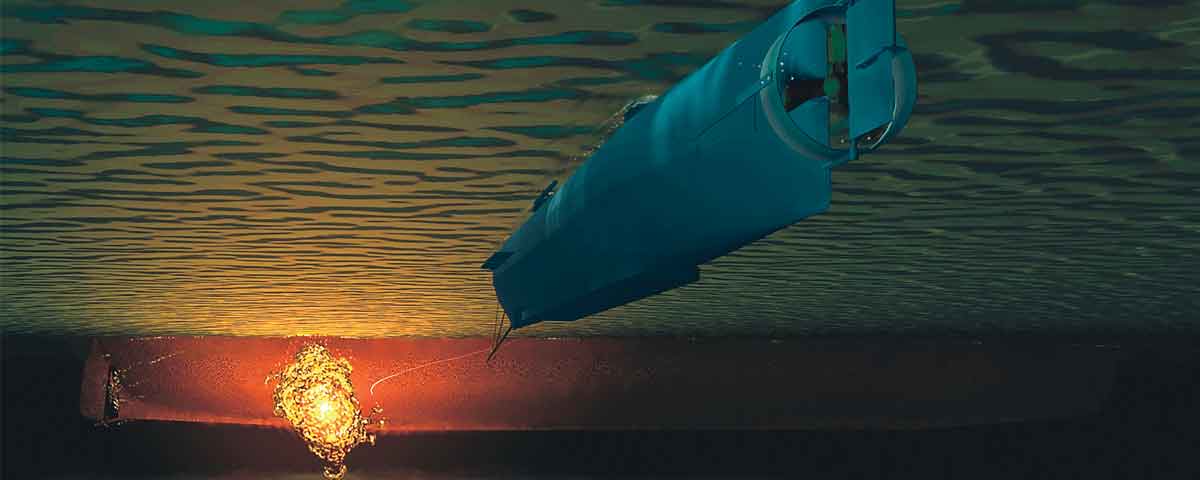

Eight committed crewmen crowded into the Confederacy’s revolutionary submersible for its first operation, it would also be its last.

[dropcap]E[/dropcap]yes strained hard, the chilly winter air and cold Atlantic breeze inducing a watery squint. These eyes were accustomed to looking out. A sailor on a cathead was staring at the water, and so was Acting Master J.K. Crosby. Both were on the deck of the USS Housatonic—a state-of-the-art steam-powered sloop boasting 12 guns and 300 crewmen, the pride of the U.S. Navy. The ship was part of a fleet whose purpose was to blockade Charleston Harbor, in South Carolina, to keep Confederates from leaving and help from arriving. This nautical siege—part of the larger naval blockade of the South called Anaconda—was far from perfect, but it had done its main job: to constrict the Confederacy. Any effort to break the blockade had to be thwarted, and for that reason, Crosby’s and the sailor’s eyes scanned the water that cold night of February 17, 1864, with focused determination.

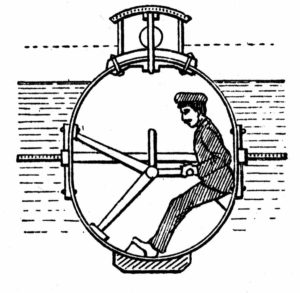

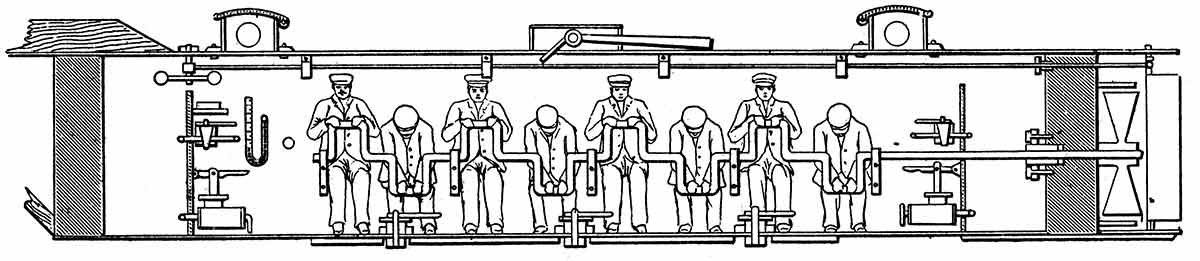

What Crosby was struggling to identify was a piece of Confederate technology that was about to make history: the H.L. Hunley submarine. Inside, eight men were crammed into what amounted to a repurposed boiler (strengthened with a skeletal frame) made of iron three-eighths of an inch thick, in a space 48 inches high, 42 inches wide, and 40 feet long.

Such extreme confinement would have been alien even to a sailor like Crosby, who was more accustomed to close quarters than were many soldiers on land. Being inside the Hunley was an experience quite unlike anything else endured by other combatants before or during the Civil War. It was born of necessity and creativity. Breaking Anaconda meant pushing men to the limits of endurance.

In precise order they sat, on a bench about a foot wide. Before them, not quite down the center of the vessel (to allow for the bench), was a long iron bar, a crankshaft, indented at the position for each seated crewmember. Each of the seven indents was possibly wrapped with a wooden sheath, enabling the men to rotate the entire crankshaft in sync. The crankshaft, in turn, was connected to a differential gearbox, which converted human energy power into propeller power, giving the submarine locomotion under the water.

At the helm was George Dixon. Dixon was likely from the Midwest, though he enlisted in Company E of the 21st Alabama Infantry in October 1861. Injured at the Battle of Shiloh, Dixon became intimately familiar with the submarine, working first at the Park and Lyons machine shop in Mobile, Ala., during the Hunley’s construction and then accompanying the vessel to Charleston. Dixon asked Commodore John R. Tucker, commander of warships in Charleston, to provide him with some men, which he did. Seated directly behind Dixon was the youngest and shortest of the crewmembers, Arnold Becker, a recent arrival from Europe. For reasons unclear, he had joined the Confederate States Navy in October 1861. Serving on the General Polk and then on the CSS Chicora, Becker was later assigned to the CSS Indian Chief, and from that vessel, he was recruited for the Hunley. Age 20 and 5 feet, 5 inches tall, Becker was at the first crank position, muscling the propeller in circles, but he was also responsible for the air-circulation system, managing the forward pump and, critically, checking the position of the valves when the sub needed positive buoyancy.

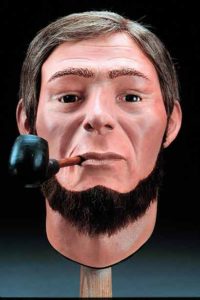

As for the second cranker, there was surely more to his name, but we know him simply as “Lumpkin,” probably his last name. From his remains, forensic science has determined that his was a life of physical exertion—and physical abuse: He was a heavy pipe smoker with the grooves worn into his teeth to prove it. He had probably served, like Becker, on the Indian Chief before joining the Hunley crew.

Two men down from the diminutive Becker—next to Lumpkin—sat a large man, well over 6 feet. This was Frank Collins. A Virginian, Collins signed up with the Confederate Navy in 1861. Like the others, he had served on the Indian Chief. His position at third crank situated him mid-vessel. In the event of a sinking, escape through either of the boat’s two conning towers, situated forward and aft, would be unlikely.

In the equally treacherous fourth crank was Corporal C.F. Carlsen, in his early 20s, whom Dixon recruited from the German artillery. Carlsen, like the others, had naval experience, having served on the Jefferson Davis. He also saw battle at Fort Walker on Hilton Head, S.C., in November 1861. It is likely that nothing had truly prepared him for the position he found himself in on that cold February night in 1864.

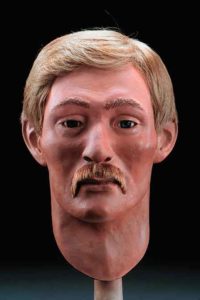

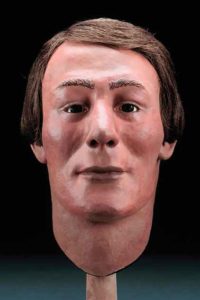

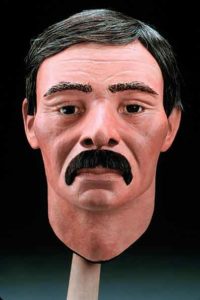

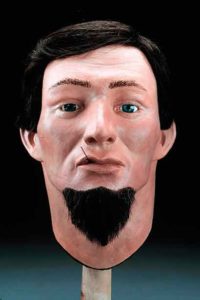

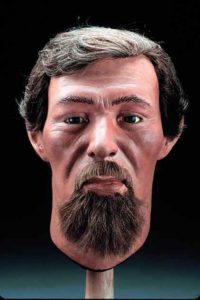

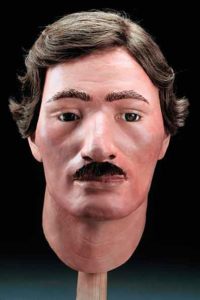

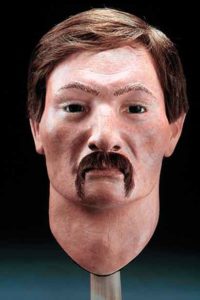

Faces of Hunley

A team of leading archaeologists and forensic experts painstakingly studied the remains of Hunley’s crew and was able to complete reliable facial reconstructions of all eight. Clues found in some of the men’s teeth convinced researchers that four were European and one was a heavy pipe smoker.

(all images Copyright © Friends of the Hunley®)

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s with Lumpkin, we know the man at fifth position only by his last name, Miller (his first name might have been Augustus). And we don’t know much more than that. He might have served with Carlsen on the Jefferson Davis, and he might have been, like Becker, a recent immigrant from Europe. Either way, he had volunteered to serve on the Hunley.

About the man in the sixth crank position, James A. Wicks, we know a bit more. Wicks had served the Union Navy early in the war, aboard the USS Congress. When the Congress was destroyed by the CSS Virginia at the Battle of Hampton Roads in March 1862, Wicks swam ashore and enlisted in the Confederacy. Like other crew members, he ended up on the Indian Chief and from there volunteered for Hunley duty. He returned from a mission in New Bern, N.C., just days before the Hunley was launched to attack the Housatonic.

Another former sailor on the Indian Chief secured the last crank position, a Marylander named Joseph Ridgaway. The son of a sea captain, Ridgaway was well-versed in nautical matters, so much so that Dixon recruited him directly for the Hunley, not only having him man the seventh crank position but also making him responsible for securing the hatch and operating the flywheel and the pump.

Two of the eight men, Dixon and Ridgaway, used more than muscle. Dixon used his eyes and ears to navigate, and Ridgaway employed his eyes and fingers for stabilizing the sub by tweaking and feathering the levers controlling the ballast tanks at the vessel’s fore. And yet, like the other crewmen, they had to contort their bodies into position.

The men ensconced in the Hunley experienced something unique, something that wouldn’t be matched for another half-century and the development of submarines and U-boats during World War I and, later, tank warfare. Intimacy meant contact with others. The men in the Hunley experienced a world more familiar to fighting in earlier ages. There were the triremes, of course, but the siege machines of both the ancient and medieval worlds offer comparisons.

Most antebellum Americans embraced an arm-stretching culture of open space. Partly, this was a product of the country’s size. News didn’t always come by word of mouth and human contact. Print and growing literacy and the intellectual forces underwriting the Enlightenment conspired to promote a more distanced, noncontact form of social interaction. Bathing, like bodily excretions, was now a private affair, and diners were not crammed on a bench. While servants in medieval Europe had often slept in the same bedroom as the master, servants in the 19th century had been relegated to a separate space, to quarters near enough for them to be summoned but removed. Touching was less necessary.

Human contact had changed and, beginning in the 18th century, the idea of private, individuated comfort began to spread from the elite downward to the middle class. By the early 19th century, ideas about comfort were understood in terms of room temperature, not body heat.

Clothing took on special meaning, since what you wore was a matter of individual choice, not a group function. It formed an outer shell against contact with the environment and with others. What people wore against their skin, in other words, said much about their station in life and their inner worth and beliefs. It also diminished the need for constant intimacy. We could be self-sustaining.

The men aboard the Hunley were practically working as a single body, their parts intertwined with the others’. Yet even in war, touching between men was prescribed and regimented. And certainly in peacetime, free white men were not really accustomed to either this intimacy or the contortions that it provided. Few occupations even began to approach the world of the submariners, and those that did were held in contempt. American observers of 19th-century English coal mines were aghast at how the mineshafts made men crawl over each other, animal-like, “with back and legs at an angle quite as acute as the pain thereby caused through underground passages that were apparently constructed for some Lilliputian race yet to be discovered.” Theirs was an unnatural world. The lack of air, the smell, the closeness of it all were a throwback to an uncivilized age, when men “naked from head to waist are at work all the time, in narrow out-of-the-way passages, where without a lamp one might consider himself as completely lost to the world in general as if imbedded in the heart of a Brazilian forest.”

On this ship, their bodies were “stowed so close” in quarters so low that they were not permitted “the indulgence of an erect posture.” The close, cramped quarters meant the “exclusion of the fresh air.” Even in cold water, the physical exertion of the crankers likely meant that inside the “climate was too warm to admit the wearing of anything but a shirt,” so that the “skin,” especially on “the prominent parts of the shoulders, elbows, and hips,” was “rubbed” aggressively by the “friction of the ship.” Dank, cramped, and forcing skin-rubbing closeness: This was the Hunley.

But this description is not, in fact, of the Hunley. It is a description of a ship of enslaved black men, women and children.

The Hunley’s men were where they were by choice. Their skin was never lacerated by a whip held by another. But in a world where white men resisted mightily any comparison to slaves, where race meant everything, where white Southern men fought to prove they were free and not slave, the similarity between the world of the Hunley and a slave ship seems uncanny. It was this willing proximity to the experience of slavery that reveals the depth of sacrifice these men were willing to make to pursue the Confederate cause.

The Hunley volunteers had willingly placed themselves in the condition of slaves—in the fight to preserve slavery. Indeed, it was a wonder that P.G.T. Beauregard didn’t crew the Hunley with at least some slaves. Why not have Dixon guide and direct the boat while slaves provided the manpower to propel it through the water? We can’t say with certainty why slave labor was not used to power the Hunley, but the answer probably has something to do with the fact that slaves were expensive (their death and loss was, after all, quite likely) and also with the same logic that kept the South from using armed blacks in combat. Manning the boat, this piece of proud Confederate technology that might break the blockade, was understood as an honor befitting only white men.

And so the Confederate crankers turned and rotated the shaft as fast as their muscles would allow, in quarters so cramped their skin rubbed and chafed, in light so dim they knew each other’s presence by contact and smell rather than by sight. But such was the importance of their suicidal mission that these men were willing to endure it all. For now, they had but one object in mind: to sink a Union ship.

The Housatonic was far too large a vessel to be redirected easily and quickly. Crosby had spotted the “something,” but it was too late: a minute after, the object beneath the ocean was alongside his ship. Hurriedly, Union sailors tried to pivot their aft guns but “were unable to bring a gun to bear upon” the object, the angle too downwardly steep, presumably. And then something hit.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Such was the importance of their suicidal mission that these men were willing to endure it all[/quote]

The extent of the explosion revealed the object below the waves: Mounted to the boat’s bottom—which made it very difficult, if not impossible, to see from the surface—was a hollow iron spar jutting out 17 feet. It looked now like a gaping fish, replete with sheeny scales. This was the Singer torpedo, carrying 135 pounds of black powder. Bolted to the spar, the copper-clad torpedo was, through the sheer momentum of Hunley, to be plunged deep into the warship’s guts and activated by a trigger fingered by Dixon.

In some ways, the torpedo had a medieval quality to it, looking not unlike a knight’s lance used in jousting. But this spar was a powerful piece of 19th-century stealth technology. Its invisibility was by design. The alternative—a torpedo dragged behind the sub and designed to hit an object when the sub dove—was far more obvious to lookouts and vigilant eyes. And it was a target easily shot at. Dixon, following trials of both torpedo designs, elected for the spar because it had the redoubtable virtue of being below the waterline and very hard to see.

Like a clenched fist at the end of a stiff arm, the torpedo was also a technology of touch. It had to be. Unlike warfare above the sea and on land, where shells could be lobbed greater distances anonymously, this underwater technology was less distanced. It required men to plant it, even in this prosthetic manner. This was maritime hand-to-hand combat. The torpedo rammed hard into the ship’s magazine, just as Crosby feared. Then…nothing. The device seems to have pierced the hull, but there was, perhaps for a minute, no immediate explosion. And then a veritable eruption. The Housatonic plunged, sinking stern first. Some sailors were stunned by the concussion; others flung themselves on the rigging, clinging for dear life. It had been all of three minutes from the sighting of “the something” to detonation.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Hunley sank the Housatonic between 8:45 and 9 p.m. Within the hour, the Union ship was swallowed by the cold waters of the bay, five of its crew missing, presumed drowned; the rest, 21 officers and 129 men, some injured by the explosion, were rescued by the USS Canandaigua. The effect was profound, the loss of the ship causing “great consternation in the fleet.” All wooden vessels were “ordered to keep up steam and go out to sea every night, not being allowed to anchor inside” the harbor. For the Confederacy, this was “the glorious success of our little torpedo boat,” which “raised the hopes of our people.”

One source at the U.S. Navy thought “undoubtedly” that the Hunley “sank at the time of the concussion, with all hands.” Whether or not that was the case, we do know that no one on the sub survived.

Ironies haunted the crew of the Hunley, even in death. It was, after all, a man by the name of J.H. Tomb, an engineer with the Confederate Navy, who believed the vessel was “a veritable coffin.” Tomb believed that there was only one relatively safe way for the Hunley to sink a ship, and that was to forgo invisibility. A spar torpedo was an effective weapon only when the boat was at the surface. “Should she attempt to use a torpedo as Lieutenant Dixon intended, by submerging the boat and striking from below, the level of the torpedo would be above his own boat, and as she had little buoyancy and no power, the chances were the suction caused by the water passing into the sinking ship would prevent her rising to the surface, besides the possibility of his own boat being disabled.” Tomb had told Dixon this before Dixon had launched his daring raid on the Housatonic; he had insisted that it was dangerous. None of this was news to Dixon. He and Tomb had even witnessed the Hunley sink on a previous dive, killing its entire crew. It was a pitiless boat.

That warning was too late now. As the submarine sank, the men—assuming they were still conscious and not knocked out by the explosion—must have known they were probably doomed. Agonizingly, they might well have known even as the sub sank. In January, before the Hunley went on its nocturnal mission, the men had deliberately let the sub sink to the ocean floor to see how long they could go without fresh infusions of air. Dixon had estimated the crew could last half an hour. It turned out they got stuck and barely escaped with their lives—two and a half hours later.

Now, time was not on their side, and the sub sank ever deeper. There was something both serene and cruel in the way the men of the Hunley faced their final moments. Decades later, their bodies were not found clumped together; each man was at his station. There had been no apparent efforts to hold hands or cling to one another. Perhaps the concussion from the explosion had knocked them out. We simply don’t know. There seems to have been no scrambling, no desperate lurch for escape, no clambering over one another, no bruising, no ripping. We know that the seven men on the Hunley who died earlier were “found in a bunch near the manhole” when the boat was brought to the surface following a failed trial run. But not the crew of the Hunley on this fateful night.

Even though they were in excruciating proximity, each man died alone at his station.

Had the men survived, they might in their excitement at the success of their mission have forgotten all the aching, stooping and skin-rubbing, and told tales of victory in the comfort of warm homes. Instead, the sub sank, dragging its already entombed crewmen to a sarcophageal grave. There they sat, at station: the dandy captain, Mr. Dixon; the anonymous Mr. Lumpkin, pipe smoker; the diminutive 20-year-old immigrant, Mr. Becker, dwarfed by the man from Virginia near him, Mr. Collins; Mr. Carlsen, whom Dixon had recruited from the German artillery; the man known only as Mr. Miller; the erstwhile Union sailor, Mr. Wicks and the sailor responsible for securing the hatch, the Marylander, Mr. Ridgaway.

They remained at the bottom of the ocean until their remains, and the Hunley, were raised and brought

to Charleston’s shore in 2000. Then, for the first time in 136 years, these men—waterlogged skeletons—were touched by human hands.

Reprinted from The Smell of Battle, The Taste of Siege by Mark M. Smith with permission from Oxford University Press USA. Copyright © Mark M. Smith, 2015, and published by Oxford University Press USA (www.oup.com/us). All rights reserved.