In early March 1814, Napoleon was outmaneuvered at Laon, France, by Field Marshal Gebhard von Blücher’s Allied army, leaving the capital city of Paris unprotected

IN EARLY NOVEMBER 1813, several weeks after his crushing defeat at Leipzig, Napoleon led fewer than 60,000 soldiers back into France and then continued on to Paris to oversee the mobilization of a new army. Meanwhile, his shattered marshals prepared to defend France’s Rhine frontier against a looming Allied invasion. They did not have to wait long. On December 20 the Grand Army of Bohemia, led by Field-Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg, crossed the Upper Rhine at Basel. Twelve days later, a smaller Allied force, Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher’s Army of Silesia, crossed the Rhine near Mainz. Schwarzenberg and Blücher had planned to reach their respective objectives of Langres and Metz by January 15.

The Allies’ ultimate target, of course, was Paris, though the specifics of such an offensive were left unsettled. Longstanding differences had become enmities among the members of Napoleon’s Coalition as they considered whether France should be invaded and whether Napoleon, in turn, should be dethroned. The Austrians did not want to invade France and desperately hoped to reach a diplomatic settlement that would keep Napoleon on the throne to counter Russia’s growing power. Tsar Alexander I of Russia wanted to be rid of Napoleon altogether.

Napoleon made his first appearance in the field on January 29, just in time to strike the rear of Blücher’s army at Brienne in northeast France. Each side sustained 3,000 or so casualties; each claimed victory. Three days later Blücher, now joined by Schwarzenberg’s forces, handed Napoleon a humiliating defeat at La Rothière about eight kilometers south of Brienne. Although Napoleon lost just 6,000 of his 45,000 combatants, he was forced to retreat in the face of the Coalition’s overwhelming numbers. The Allies might have ended the war with a general pursuit, but Blücher lacked fresh reserves and Schwarzenberg’s rearward units remained too distant to participate. Nonetheless, as long as their armies stayed together, a victory for Napoleon seemed impossible.

Unbelievably, the two Coalition armies separated. In the aftermath of the victory at La Rothière, the Allies decided that the march on Paris should commence, with Blücher’s army advancing along the Marne River and Schwarzenberg’s down the Seine. That decision gave Napoleon an opening to mask the slow-moving Schwarzenberg and launch what would become known as the “Six Days’ Campaign” against Blücher. Beginning on February 9, he defeated Blücher’s Prussians and Russians in four battles. Fortunately for Blücher, however, Schwarzenberg’s crossing of the Seine prompted Napoleon to disengage and head south to contend with the Army of Bohemia. After reorganizing and receiving reinforcements, Blücher had the Army of Silesia marching in just two days to answer Schwarzenberg’s call for help. As things would turn out, failing to finish off Blücher’s army amounted to a catastrophic error on Napoleon’s part.

On February 17, Napoleon, with 55,000 men under his command, stopped the advance of Schwarzenberg’s 120,000 men at Mormant, less than 50 kilometers southeast of Paris. After learning of Blücher’s crushing defeat, Allied commanders ordered a general retreat 100 kilometers southeast to Troyes. Over the next few days, Napoleon gathered his forces at Nogent-sur-Seine. Meanwhile, Schwarzenberg reassembled the Army of Bohemia at Troyes and Blücher reached Méry-sur-Seine in a flank position that deterred Napoleon from advancing. Nonetheless, in the face of unrelenting pressure from Napoleon, Schwarzenberg decided that he should retreat another 120 kilometers southeast to Langres and Blücher nearly 200 kilometers east to Nancy. On learning of Schwarzenberg’s decision, however, Blücher feared a withdrawal across the Rhine would come next. Consequently, he requested permission for the Army of Silesia to march north, cross the Marne, and unite with two corps from the Army of North Germany for another advance on Paris. Schwarzenberg approved and decided that for the moment the Army of Bohemia would retreat only 50 kilometers east to Bar-sur-Aube.

Schwarzenberg commenced his withdrawal on February 23, and the following day Blücher began his advance. On February 25, Napoleon took the bait and furiously drove his men after Blücher. Reaching the Marne on March 1, Napoleon found himself at a crossroads: Should he continue pursuing Blücher or did he need to contend with Schwarzenberg? His plan for defeating the Army of Bohemia entailed the operation that Schwarzenberg feared most. “I am prepared to transfer the war to Lorraine,” he informed his brother Joseph, “where I will rally my troops that are in my fortresses on the Meuse and the Rhine.” Thus, the master planned his famous manoeuvre sur les derrières to turn Schwarzenberg’s right flank and operate against his rear.

Had Napoleon implemented this plan immediately, Schwarzenberg undoubtedly would have retreated headlong to the Rhine. The evidence to support this assumption is clear. With Blücher north of the Marne, Schwarzenberg would have seen an envelopment of the Army of Bohemia’s right wing, along with Napoleon’s appearance on the Rhine, as a monumental calamity.

But instead of terrorizing Schwarzenberg, whose retreat eventually would have forced Blücher to renounce his own operations, Napoleon changed his mind, opting to continue his pursuit of the Army of Silesia. He based this decision on his overwhelming concern for Paris and the threat posed to it by Blücher’s army. Napoleon thus hounded Blücher, who fled further north to the Aisne River. There, he united with the two corps from the Army of North Germany, whose commanders had convinced the French to surrender Soissons and its bridge over the Aisne on March 3. Using the city’s stone bridge as well as its own pontoons, the Army of Silesia miraculously escaped across the Aisne with Napoleon closing fast.

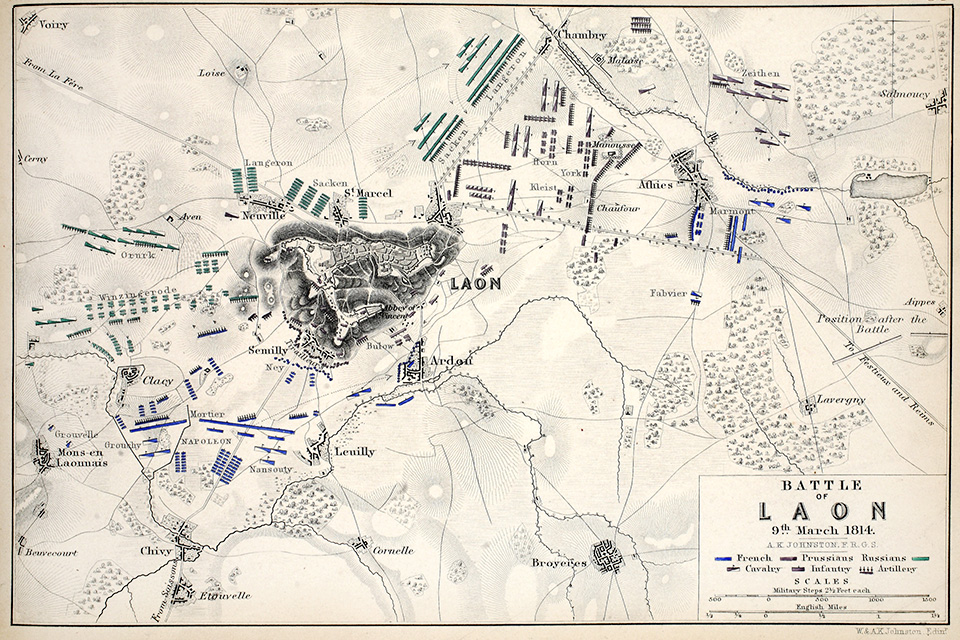

After Napoleon defeated Blücher’s Russians at Craonne on March 7, the Prussian commander concentrated his army at Laon, a French city situated on a high, steep-sided hill. By taking Laon, Napoleon aimed to sever the enemy’s line of operation and secure Paris by driving off the aggressive Blücher. He could then rally the garrisons of his northeastern fortresses and, thus reinforced, fall on Schwarzenberg, who no doubt would be retreating after learning of Blücher’s latest setback. On March 8, believing he would find only a rearguard at Laon, Napoleon decided to approach the city in two widely separated columns—an extremely risky operation because the distance as well as the rough and broken terrain between his two columns ruled out mutual support. Nevertheless, Napoleon led his main body of 37,000 men northeast from Soissons toward Laon while Marshal Auguste-Frédéric de Marmont marched northwest on the Reims highway with some 9,500 men. Between them stood Blücher with nearly 100,000 men and 600 cannons.

General Ferdinand von Wintzingerode’s Russian corps, with 25,200 men, formed Blücher’s right wing and rested on the village of Thierret, where its vanguard took position with forward posts extending southwest. Lieutenant General Friedrich Wilhelm von Bülow’s Prussian III Corps, with 16,900 men, held Blücher’s center and received the task of defending the city. General Hans David von Yorck’s Prussian I Corps, with 13,500 men, and Lieutenant General’s Prussian II Corps, with 10,600 men, provided the left wing, which was slightly echeloned to the northeast and faced the roads leading to Athies and Reims. Two additional Russian corps commanded by Generals Louis Alexandre de Langeron and Fabian Gottlieb von der Osten-Sacken, with nearly 38,000 men between them, remained in reserve north of the Laon height. Blücher, suffering from fever and eye inflammation, ordered his commanders to maintain a strict defensive posture until Napoleon deployed his forces. As soon as Napoleon revealed his intentions, Blücher planned to launch a crushing counterattack.

NAPOLEON OPENED HIS ATTACK on the evening of March 8 by having Marshal Michel Ney’s Young Guard corps drive the Russians from Étouvelles. Two hours after midnight, Ney pressed the attack, gaining Chivy and, by daybreak, had pushed the Russians to Semilly. Heavy snow had fallen throughout the night, and by dawn a thick mist veiled the whole countryside. Around 7 a.m., Ney directed Major General Pierre Boyer’s brigade east against Semilly, while a division led by Brigadier General Paul Jean-Baptiste Poret de Morvan marched northeast from Leuilly toward Blücher’s center at Ardon. Preceded by a considerable cannonade, Boyer opened his assault on Semilly at 9 a.m., but the Prussian defenders, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Friedrich von Clausewitz, repulsed several attacks. Meanwhile, Poret de Morvan’s men took advantage of the poor visibility to surprise the Prussians at Ardon and drive them back some 1,000 meters to the foot of the Laon height. A counterattack pushed the French back to Ardon, which Poret de Morvan’s men held.

By 11 a.m. the pale winter sun had burned off the mist. From his vantage point on the ramparts at the foot of a bastion called Madame Eve, Blücher surveyed the thin French battalions deployed before Laon and contemplated his adversary’s next move. Refusing to believe that Napoleon would attack with such a small force, he became concerned that the actual attack would come from another direction. At noon Blücher learned that a strong French column was approaching from Festieux, 12 kilometers north of Craonne, where the two armies had engaged on March 7. He assumed that the Festieux column probably made up the majority of Napoleon’s army and would deliver the main blow. Consequently, the linchpin of the French position seemed to be the village of Ardon. Believing that Napoleon’s main attack would be against the left wing, Blücher cautiously decided to retake Ardon and probe the intentions of the enemy force opposite his right.

On the morning of March 9, Wintzingerode’s 12th Infantry Division attacked the French left between Clacy and Semilly. At the same time, four hussar regiments, numerous Cossack squadrons, and some light artillery batteries from Sacken’s corps moved around Blücher’s right to menace Ney’s extreme left and rear. After Wintzingerode forced the French out of Clacy, the Russians attempted to debouch west toward Mons-en-Laonnais, but Ney unleashed a powerful counterattack that forced the Russians back into Clacy. After Poret de Morvan was mortally wounded, Bülow’s 6th Brigade drove the two French Guard battalions occupying Ardon to Leuilly. At this moment, Napoleon finally arrived in Chavignon, some 14 kilometers southwest of Laon.

As soon as 6th Brigade had secured Ardon, Blücher planned to send Bülow’s entire Reserve Cavalry south through Ardon to Cornelle to envelop Ney’s right. Yet fresh doubts seized him. Blücher knew enough about Napoleon’s art of war to question whether he would leave his two wings so widely separated without a middle column to connect them. This thought raised concerns that a third column would soon appear at Bruyères, some six kilometers south-southeast of Laon. Consequently, until the road through Bruyères could be reconnoitered, and the strength and intentions of the Festieux ascertained, Blücher refused to order a general attack and so recalled Bülow’s 6th Brigade and Reserve Cavalry. Soon Ardon again fell to a counterattack led by Mortier. In addition, around 3 p.m., Blücher received a second report that reinforced the idea that the Festieux column would deliver the main attack. As a result, Blücher moved Sacken and Langeron to the left wing, as reserve for Yorck and Kleist, and ordered the two Prussian corps commanders to attack the enemy as soon as possible. To have the maximum number of cavalry regiments available for use on the open terrain to his left, he recalled Sacken’s cavalry, which by then had reached Ney’s rear.

Throughout the day, numerous couriers had been dispatched with orders for Marmont to accelerate his march, but all had been captured or driven off by the Cossacks. For his part, Marmont made no effort to establish communication with Napoleon. Assuming that Marmont was nearby, Napoleon ordered an attack on Blücher’s right to induce him to transfer reinforcements from his left. He hoped that this diversion would give Marmont the element of surprise against Blücher. Around 4 p.m. the battle again became heated. On Napoleon’s order, the lead division of General Henri François Charpentier’s corps, supported by one of Ney’s divisions, succeeded in driving the Russians out of Clacy, yet Bülow’s 6th Brigade recaptured Ardon.

MARMONT’S VANGUARD HAD CLEARED FESTIEUX just after 10 a.m., but the corps halted there until noon rather than march to the sound of Napoleon’s guns. Around 3 p.m. his lead column approached Athies. An hour later, Major General Jean-Toussaint Arrighi de Casanova led an attack that drove the two Prussian battalions from Athies. After Marmont deployed his cavalry against the left flank of the Allied army, Yorck and Kleist sent their combined cavalry under General Friedrich Wilhelm von Zieten southeast through Chambry toward Athies and a position facing Marmont’s right flank. With four Allied corps in his immediate front and a large cavalry mass threatening his right, Marmont had enough sense not to engage such superior forces. He ordered his soldiers—many of them teenagers or sailors who knew little about field service—to bivouac on the field. The marshal passed the night at the Eppes château, six kilometers southeast of Athies.

While Blücher could see the fight at Athies from Laon, a strong westerly wind muted the sound of the guns. Napoleon, who was farther away, could not hear the guns at all, and the smoke and topography prevented him from seeing Marmont’s attack. Knowing nothing of Marmont’s movements, and with the light of day quickly fading, Napoleon decided to break off combat around 5 p.m.

By nightfall, Blücher, with the benefit of enough reports from the field, no longer feared the approach of a third enemy column from Bruyères. Moreover, the Festieux column was estimated at fewer than 10,000 men. Statements from prisoners confirmed that Napoleon had joined Ney’s forces. Based on this news, Blücher ordered a surprise attack to destroy Marmont.

It was a dark night, with the only light provided by the smoldering ruins of Athies. At 6:30 p.m., six Prussian battalions followed by the rest of Yorck’s I Corps advanced against Marmont’s center. The Prussians entered Athies without firing a shot, surprising and dispersing Brigadier General Edme-Aimé Lucotte’s brigade of Arrighi’s division. To the right of Yorck, Kleist’s II Corps marched across the fields between Athies and the Reims highway to smash Marmont’s left. Zieten, commanding some 7,000 sabers, now charged through the woods of Salmoucy on Marmont’s right and ravaged the bivouac of the 2,000 troops of I Cavalry Corps just as they were mounting their steeds. The French resisted with great courage, and in the darkness bitter hand-to-hand struggle ensued. Marmont’s VI Corps soon fled.

The Prussian infantry halted at Aippes while the cavalry pursued Marmont, who briefly resisted at Festieux before retreating further. Only the cavalry and a few battalions crossed the Festieux defile to pursue the enemy on the other side. Almost all of the Prussian infantry returned to Athies with detachments holding Festieux and Aippes. At 2 a.m., some seven hours after the surprise attack, Marmont reported to the emperor: “We still have not been able to restore order among the troop units, which are all mixed together and are incapable of making a movement; it is impossible for them to perform any service, and, since a considerable number of men are marching to Berry-au-Bac, I see myself forced to proceed there to reorganize.” Marmont had lost more than 3,500 men, including 2,000 who had been taken as prisoners, as well as 45 guns and 131 caissons. The Prussians had lost 850 or so men.

With wind howling throughout the night of March 9, Napoleon’s outposts did not hear the combat at Athies. Consequently, the emperor made plans for a double envelopment of Blücher’s position the following morning. His staff had already issued the orders when, around 1 a.m., news arrived of Marmont’s debacle. At first, Napoleon refused to believe it; then he received a report from a dragoon post at Nouvion-le-Vineux, written at 2:30 a.m., stating that VI Corps had been completely defeated at around 7 p.m. Assuming that Blücher would pursue Marmont, he decided to remain before Laon and attempt to catch Blücher’s columns debouching from their positions. On the open plain, Napoleon reasoned, his superior skills would compensate for his inferior numbers.

Related Content From MHQ

Feature Story: “Holding the Farm at Waterloo,” by Brendan Simms

Book Review: Napoleon, a Life, by Andrew Roberts

Book Review: Russia Against Napoleon: The True Story of the Campaigns of “War and Peace,” by Dominic Lieven

Book Review: Citizen Emperor: Napoleon in Power, by Philip Dwyer

Book Review: Armies of the Napoleonic Wars, edited by Chris McNab

On March 10, pleased by the apparent victory, Blücher issued orders for the entire army to pursue the French. Yet at daybreak, just as his army started to march, Blücher was astonished to see that Napoleon had not only maintained his old position but had arranged his troops for a new attack. Blücher immediately ordered all corps to return to their previous positions; only Wintzingerode would take the offensive. At around 9 a.m., the corps of Ney, Charpentier, and Mortier formed for the defense of Clacy; Pierre Boyer’s division occupied the brickworks of Semilly, while the right wing extended to Leuilly. Wintzingerode’s Russians launched repeated attacks but could not achieve decisive results. Consequently, Blücher ordered Bülow to shift some battalions from the center to assist the Russians. Observing Bülow’s movement and concluding that Blücher had finally accepted battle, Napoleon ordered the division holding Clacy to assault the Russians; Ney led two divisions in a failed effort to take Semilly and Ardon.

Finally convinced that Blücher did not intend to move, Napoleon ordered the retreat to Soissons to commence at 6 p.m. On March 11 a weak rearguard of two battalions, 300 cavalry, and two guns abandoned Clacy only an hour before daybreak. With Blücher ailing, the Army of Silesia did not pursue Napoleon, allowing him to slip away with 24,000 men.

While exacting some 4,000 Allied casualties, Napoleon had lost 6,000 men in addition to Marmont’s 3,500. It was clear that he could not sustain the losses in men, matériel, and morale. “Unfortunately, the Young Guard is melting like snow,” he informed his brother Joseph. “The Old Guard maintains its strength. Yet the Guard Cavalry is also shrinking considerably.”

The battle of Laon presented Napoleon with the last opportunity to change the course of the war by defeating Blücher—an event that most certainly would have prompted Schwarzenberg to retreat. Feeling that the war had taken a turn for the worse, concern for Paris mastered him. “[Blücher’s] army is much more dangerous to Paris than Schwarzenberg’s,” he wrote. “For all circumstances, I am going to move closer to Soissons in order to be closer to Paris; but until I have been able to engage this army in a battle, threaten it anew, it is very difficult for me to turn elsewhere.”

On March 11, Napoleon instructed his brother to build redoubts on the hills that overlooked Paris, especially Montmartre. Joseph also received orders to implement a levée-en-masse of the National Guard to raise and arm 30,000 men from the refugees who had fled to Paris and the city’s unemployed. These measures, however, caused overwhelming panic and political agitation that ultimately led to his political demise. Although he would win minor victories at Reims on 13 March and St. Dizier on March 26, the master was out of time. By chasing Blücher to Laon, Napoleon had granted Schwarzenberg one too many reprieves. By failing to inflict serious losses on the Army of Silesia, he had lost the best opportunity to influence Schwarzenberg’s operations.

It did not help that Napoleon’s own intransigence had led the Allies to conclude that a diplomatic settlement was unattainable. While Napoleon was operating against Blücher, Schwarzenberg had resumed the offensive. With the Army of Bohemia closing on Paris, Napoleon no longer had time to “transfer the war to Lorraine.” Any attempt to go east and turn Schwarzenberg’s right flank could result in the Allies reaching Paris before they could feel the effects of his manoeuvre sur les derrières. Unable to smash Schwarzenberg’s rearguard at Arcis-sur-Aube on March 20–21, Napoleon found the two enemy armies between himself and his capital.

The end came quickly. On March 31, Marmont surrendered Paris; Napoleon unconditionally abdicated six days later. MHQ

MICHAEL V. LEGGIERE is professor of history and deputy director of the Military History Center at the University of North Texas. He is the award-winning author of five books on the Napoleonic Wars including a biography of the Prussian field marshal Prince Blücher and monographs on Napoleon’s campaigns in 1813 and 1814.

MAP: Alexander Keith Johnston, Battle of Laon, published by William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh & London, 1848 / The Stapleton Collection / Bridgeman Images

[hr]

This article originally appeared in the Autumn 2016 issue (Vol. 29, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: How Napoleon Lost Paris, 1814.

Want to have the exquisitely illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!