Throughout the history of warfare, deception has played a pivotal role in the outcome of battles and campaigns. From the Trojan Horse to our modern stealth technology, there are no bounds to which combatants have not gone in their attempts to dupe an unsuspecting foe into committing a fatal error. What is interesting is that, however simple or complex they may be, most well-executed ruses will succeed. Technology may change, but human nature does not — and war is a very human occupation in which the mind and the senses are easily tricked. This was certainly the case during the Civil War. Occurring as it did in the midst of one of the greatest transitional periods in the annals of combat, the Civil War presented many opportunities for guile and trickery. This is borne out by the abundant incidents of deception found throughout the Official Records, as well as memoirs, letters and even war literature. A sampling of the ruses adopted by Union forces is presented here, in the first of a two-part series.

‘All three corps are crossing the mountains…I think we shall deceive the enemy as to our point of crossing. It is a stupendous undertaking.’ With these words, Union Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans inaugurated one of the most brilliant strategic deceptions of the entire war. The date was August 16, 1863, and as he stepped off on what would come to be known as his Chickamauga campaign, Rosecrans’ primary objective was to get his army across the broad Tennessee River. This he hoped to accomplish without being detected by Confederate General Braxton Bragg, whose forces were then situated on the opposite bank at the strategically important rail center of Chattanooga.

In Napoleonic style, Rosecrans sent the bulk of his army on a wide southwesterly sweep toward a series of river crossings. To draw Bragg’s attention away from this movement, he ordered Brig. Gen. William B. Hazen to feint an attack on Chattanooga. Spearheading Hazen’s advance was Colonel John T. Wilder’s mounted Lightning Brigade. Using obscure trails, Wilder’s troopers covertly made their way east before finally veering south toward Chattanooga, capturing a considerable number of bewildered Rebels along the way. Over the course of the next three weeks, the imaginative Wilder was instrumental in convincing Bragg that Rosecrans was moving in force against Chattanooga from the north. This episode is perhaps best described in Wilder’s official report: ‘We then commenced making feints as if trying to cross the river at different points for 40 miles above the town, and succeeded in so deceiving them as to induce them to use an entire army corps to prevent the execution of such a purpose….Details were made nearly every night to build fires indicating large camps, and by throwing boards upon others and hammering on barrels and sawing up boards and throwing the pieces in streams that would float them into the river, we made them believe we were preparing to cross with boats.’

Entirely taken in by Wilder’s scheme, Bragg held to his conviction that the main enemy thrust would come from the north, despite reports of Federal crossings to the south of Chattanooga. By the time Bragg realized he had been hoodwinked, it was too late. Screened by 9,000 cavalrymen, Old Rosy’s columns had crossed the river virtually unimpeded and were now poised on the Confederate rear, thus rendering Chattanooga untenable. On September 7, Bragg reluctantly abandoned the railhead. ‘Chattanooga has been taken without a struggle,’ wrote an exultant Rosecrans on the 9th. His elation would be short-lived, however. Barely two weeks later, Rosecrans watched almost helplessly as fate turned its back on him during the ensuing debacle that took place along the banks of Chickamauga Creek.

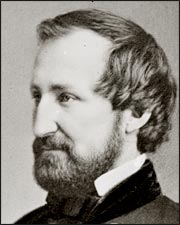

|

| Union Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans successfully duped General Braxton Bragg in August 1863 and crossed the Tennessee River virtually unopposed to take Chattanooga. (Library of Congress) |

In many respects Rosecrans’ maneuver around Chattanooga had mirrored Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Vicksburg strategy only four months earlier. By his use of various feints, including Colonel Benjamin Grierson’s celebrated raid through central Mississippi, Grant managed to divert the enemy’s attention while his columns marched south along the west bank of the Mississippi and crossed over at Bruinsburg. Unlike Rosecrans’ ill-fated campaign, Grant’s endeavors would culminate in the siege and eventual downfall of Vicksburg, as well as the surrender of 29,000 Confederates.

If Rosecrans’ exploits illustrate anything, it is that the Confederates did not hold a monopoly on subterfuge. Given the opportunity, Yankees could be just as crafty as their Southern counterparts, proving it over and over again at such places as Vicksburg, South Mountain and Chattanooga. In his book Chancellorsville, Stephen W. Sears recounts how even the indomitable Robert E. Lee was treated to some of his own medicine in April 1863.

As a prelude to his spring offensive, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker ordered Maj. Gen. George Stoneman to lead 9,800 cavalrymen on a raid against Lee’s vital Richmond/Fredericksburg supply line. Hooker reasoned that Lee, upon learning that his communications with Richmond had been severed, would be compelled to abandon his Rappahannock line and withdraw southward. Meanwhile, from his position astride the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac Railroad, Stoneman was expected to check Lee’s retreat until Hooker’s main force could fall on the Confederate rear. In order to mask Stoneman’s objective, Maj. Gen. Daniel Butterfield — Hooker’s chief of staff — devised a ruse that was to bear more fruit than even he could have imagined.

Aware that the Rebels had broken the Union signal codes, Butterfield arranged for a semifictitious message to be sent by flag. Phrased in the form of ‘casual signalman-to-signalman talk,’ it read: ‘Our cavalry is going to give Jones & guerrillas in the Shenandoah a smash. They may give Fitz Lee a brush for cover. Keep watch of any movement of infantry that way that might cut them off & post Capt. C.’ According to Hooker’s calculations, a cavalry clash with Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee at Culpeper was anticipated. Butterfield’s allusion to a subsequent movement into the valley was totally false, however, and designed to draw Marse Robert’s attention away from Stoneman’s true destination.

As hoped, the message was intercepted, decoded and forwarded to Lee, who took it at face value. On April 14, Lee wired Brig. Gen. William ‘Grumble’ Jones: ‘I learn enemy’s cavalry are moving against you in Shenandoah Valley; will attack Fitz in passing….General Stuart, with two brigades will attend them. Collect your forces and be on your guard.’ Later that day, his anxieties for Jones increased when Stoneman’s riders were observed heading in Fitz Lee’s general direction, just as the intercepted message had predicted. The hook had been baited. Now fully convinced that Butterfield’s message was authentic, Lee began shifting his entire cavalry to the north and west as a precaution against Stoneman’s anticipated movement into the valley. As a result of these new dispositions, Lee had created a 20-mile gap in his line.

When Hooker learned of the breach in Lee’s defenses, he immediately devised what Confederate Colonel E.P. Alexander described as ‘decidedly the best strategy conceived in any of the campaigns ever set on foot against us.’ Having altered his plans, Hooker now secretly marched three Union corps through the void and into the Confederate rear and left flank, moves that culminated in the Battle of Chancellorsville.

In all respects, ‘Fighting Joe’s’ strategy should have succeeded in destroying the Army of Northern Virginia. In the end, however, Lee turned the tables on his truly luckless opponent when he sent Lt. Gen. Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson on his famous march around Hooker’s own exposed flank. Whether the result of seeing a substantial portion of his line crumble under Jackson’s attack or as a consequence of being knocked senseless by an exploding artillery shell, Hooker lost confidence and eventually withdrew his forces back to the north bank of the Rappahannock. If Butterfield despaired over these events, he could take some consolation in the knowledge that his trick had played a central role in what perhaps is the greatest Union might-have-been of the entire war.

Throughout the war, both sides became particularly adept at ruses involving the use of fake cannons. Popularly known as ‘Quaker guns,’ these were usually nothing more than logs whose contours had been shaped to resemble full-size artillery pieces. Once the logs were painted black and mounted onto wheels, it was virtually impossible from a distance to tell them apart from the real McCoy. Strategically placed, these bogus batteries could effectively transform a thinly defended line into one that was bristling with cannon muzzles, and they were often instrumental in thwarting the enemy.

|

| ‘Quaker guns’ — i.e., anything that could be made to look like artillery from afar — were a favorite ruse of both sides. (Library of Congress) |

Due in part to the North’s preponderance in men and materiel, the Quaker gun was not as widely used by Federal commanders. But this is not to say the Yankees were above resorting to the age-old ploy on occasion. At New Mexico’s Fort Craig, Colonel E.R.S. Canby certainly had no qualms in this regard. In early 1862, Canby learned that Confederate Brig. Gen. Henry Sibley had left Texas with a sizable force and was making his way toward Fort Craig. Determined ‘to retain this post to the last extremity’ and wishing to put on as bold a front as possible, Canby bolstered the fort’s defenses by interspersing a collection of Quakers with his genuine batteries. Arriving in the vicinity, Sibley sent a reconnaissance in force to within a mile of the fort. If the following excerpt from Sibley’s report is any indication, the Quakers made a material impression: ‘The reconnaissance proved the futility of assaulting the fort in front with our light metal.’ Unwilling to test the fort’s defenses and in need of provisions, Sibley instead chose to conduct a raid on Union supply depots at Albuquerque and Santa Fe. From atop Fort Craig’s adobe bastions, Canby’s men, some probably regarding their wooden replicas with a degree of affection, would have watched as the dust from Sibley’s columns disappeared into the horizon.

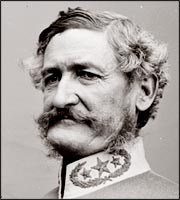

|

| At Fort Craig, N.M., Union Colonel E.R.S. Canby (top) successfully used Quaker guns to discourage an assault by forces of Brig. Gen. Henry Sibley (above), then took the offensive against them after Glorieta Pass. (Library of Congress) |

|

Ultimately, Sibley’s New Mexico campaign came to a disastrous end following a run-in with Major John Chivington’s 1st Colorado Volunteers at Glorieta Pass on March 26-28. Their already dwindling supplies having been destroyed by Chivington, Sibley’s worn and starving remnants trudged back to Texas, all the while harassed by Canby and the now considerably emboldened men of Fort Craig. Canby, for his part, was promoted to brigadier general on March 31 immediately following the victory.Throughout the war, it was not uncommon for the Rebels to substitute Quaker guns for the real variety as a means of masking a withdrawal. Not to be outdone, the Federals returned the favor on at least two occasions, the first in August 1862 at Harrison’s Landing, Va.

Before complying with Abraham Lincoln’s order to abandon their hard-earned position along the James River, a few of the more creative members of the Army of the Potomac left a welcoming committee of sorts for the Rebels, who they knew would move in on the landing following their withdrawal. Complete with stuffed dummies, the scene was reminiscent of a similar feint that Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard used at Corinth, Miss. According to some accounts of the Harrison’s Landing affair, it was days before the Rebels drew up enough courage to approach the position.

In a second incident, a band of civilians from Frankfort, Ky., took matters into their own hands when left to fend for themselves against Colonel John Hunt Morgan’s Rebel cavalry. In the midst of the 1862 Confederate invasion of Kentucky, Union troops had been forced to abandon the state capital. Before withdrawing they removed two ‘monster cannons’ from a hill overlooking the area south of town. That night a few of the townsmen came up with the idea of replacing the guns with two empty beer kegs, which they then disguised with a tarpaulin. The story goes that, all the next day, Morgan’s cavalrymen roamed about the surrounding countryside but dared not enter Frankfort for fear of being fired on by the two supposed guns. Finally, on the second day, they ‘made a bold and daring charge on the `tarpaulin beer-keg battery’ and captured it without the loss of a man.’ Only then did the sheepish Confederates become aware that the Federals had left Frankfort, prompting one of them to comment on how they had been’sold by the Yanks.’ Reveling in their success, the pranksters would later boast about how they ‘and the two empty beer-kegs had kept the Rebels from burning all the bridges around Frankfort.’

Combat subterfuge was no less effective on water than it was on land. In the naval category, top billing must go to one memorable if not bizarre ruse that took place near Vicksburg in February 1863.

Following a heavy engagement, the crewmen of the severely damaged USS Indianola ran their gunboat aground before they were forced to surrender. Never before had a Federal ironclad fallen into enemy hands, and Indianola‘s capture must have been a source of considerable irritation for Rear Adm. David D. Porter, in overall command of the U.S. flotilla.

Several days after the Indianola incident, Porter set adrift an old coal barge that, with a bit of imagination and some salvaged materials, had been made to look like a massive 300-foot ironclad. The prank, whose object had been to entice the Vicksburg batteries into wasting ammunition, was to yield wholly unexpected dividends.

As expected, the wooden behemoth drew fire as soon as it came into range of the Rebel guns. ‘Never did the batteries of Vicksburg open with such a din,’ wrote a gleeful Porter. To the surprise of many, the counterfeit ironclad somehow managed to make it through the gantlet and continued floating downstream toward the site of the still-beached Indianola. On board the captured vessel was a group of Rebel salvagers, who were then hard at work trying to dislodge the boat. Totally unnerved by the sudden appearance of Porter’s creation, a group of Confederate gunboats, whose crews had been assigned to keep watch over Indianola, high-tailed it to safety. Left to fend for themselves, Indianola‘s salvagers reluctantly blew up their prize and made for shore. Whether he had intended it or not, Porter managed to have his cake and eat it, too.

The use of deception was not strictly reserved for the upper echelon. From colonels on down to privates, fighting men on both sides were often forced to resort to guile in order to avoid being killed or captured.

Perhaps the most memorable illustration of that kind of deception would be Colonel Joshua L. Chamberlain’s famous charge at Little Round Top on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg. After hours of fending off one Confederate attack after another, Chamberlain’s 20th Maine had run out of ammunition and probably would not have been able to hold against another onslaught. Aware of his precarious situation and of the calamity that would befall the Union left flank should his line give way, Chamberlain ordered his men to fix bayonets and charge the oncoming enemy. In a textbook example of a right-wheel maneuver, the 20th went careening down the slope. Although most were wielding empty rifles, Chamberlain’s stalwarts quickly overwhelmed and beat back their awe-struck opponents. Chamberlain had bluffed his way out of his predicament — and in the process likely saved the Union’s fortunes that day.

Although few incidents may be as dramatic as Chamberlain’s feat, there are many other examples of crafty deeds from within the ranks. At South Mountain, Private James Allen of the 16th New York single-handedly captured 14 enemy soldiers by employing a bit of cunning and panache. After becoming separated from his regiment, Allen came upon a small group of Southerners who proceeded to fire one or two volleys in his direction. At this, Allen began waving to an ‘imaginary company’ that was supposedly approaching from an area to his rear, all the while calling out, ‘Up men, up!’ Ordered by Allen to surrender and apparently believing they were cornered, the Confederates stacked arms and surrendered. Not taking any chances, Allen — his own musket in hand — immediately positioned himself between the Confederates and their rifles until help finally arrived and his befuddled prisoners could be taken away.

In another similar incident, Lieutenant James Hill of the 21st Iowa stumbled upon three Confederate pickets while riding through dense woods near Champion’s Hill (or Champion Hill), Miss. Isolated and with three enemy muskets aimed at him, Hill quickly composed himself and nonchalantly ‘ordered the Johnnies to `ground arms.” Hill had been so convincing that his would-be captors immediately obeyed. Continuing with the charade, Hill ordered an imaginary guard to come to a halt. As their view of Hill’s ‘guard’ was obscured by the heavy underbrush, the enemy pickets suspected nothing. Issuing another series of orders, Hill then marched the guard and his more than compliant captives back to Union lines. As was Chamberlain, both Hill and Allen were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions.

Not quite so notable but no less worthy of mention are many other exploits, including those of Union Colonel Charles G. Harker. As he pushed his brigade forward at Chickamauga, Harker became aware of a numerically superior Rebel force on his front. Undeterred, he cleverly deployed the bulk of his brigade into line of skirmish. Ordinarily, one or two companies of skirmishers would have been indicative of an advancing regiment on the battlefield. Seeing Harker’s massive array of skirmishers bearing down upon them, the Rebels were duped into believing they were up against an entire division and promptly withdrew. For this and other acts of gallantry at Chickamauga, Harker was promoted to brigadier general. He is only one of the many unsung heroes whose acts of cunning have gone relatively unnoticed in history books.

Given their vaunted Yankee ingenuity, it is not surprising that the Northern rank and file had a natural flair for slyness. But however adept they may have been at duping the enemy, Federals were not immune to having the wool pulled over their own eyes. After all, ‘Every good trick deserves another,’ and as more than a few Union commanders were to learn, the Confederates had more than a fair share of tricks up their sleeves.

This article was written by Maurice D’Aoustand originally published in the May 2006 issue of Civil War Times Magazine.

For more great articles, be sure to subscribe to Civil War Times magazine today!