He was an enemy alien living in China when Claire Chennault recruited him into the American Volunteer Group. The Flying Tigers knew him as “Herman the German.” He would rebuild—twice—the first Japanese Zero to fall into American hands, and sneak behind enemy lines on daring missions for the OSS. It took the U.S. secretary of war’s approval to get him into the Army Air Forces, and an act of Congress to finally make him a U.S. citizen. But that was just the beginning of a long aviation career that would see him earn accolades for innovative jet engine design.

Gerhard Neumann was born into a Jewish family in Frankfurt an der Oder in 1917. At age 16 he was apprenticed to a tough old master mechanic, and he later attended Germany’s prestigious Mittweida technical college. In April 1939, he set off for China, but when he arrived in Hong Kong he found that the Chinese transport agency that had hired him had vanished. He talked his way into a job with a local auto repair company, and within days was swearing in Chinese and running the shop.

Three months later, when Britain and Germany went to war, the young German found himself behind barbed wire. He was soon released, but in June 1940 the British confiscated his passport and gave him a choice: Leave Hong Kong within 48 hours or be shipped to an internment camp in Ceylon. Neumann knew that without a passport he would not be admitted by any neutral country, so he decided to try for a job with the Chinese National Aviation Corporation. With his parole due to expire at midnight, he was told to come back the next day. Leaving the CNAC office he met a Pan American Airways executive, a sympathetic American who put him on a plane for Kunming, China, minutes before midnight.

Neumann arrived in Kunming with an introduction to a retired U.S. Army captain, Claire Lee Chennault, then serving as chief adviser to the Chinese air force. This wasn’t the time to get into Chinese aviation, Chennault told him, and recommended that he try the local Renault plant. The Burma Road was almost finished, and the plant was building the trucks that would be used on it. The German engineer joined Renault and was chosen to lead the first convoy on the Burma Road—an exploration of primitive roads over inhospitable mountain terrain and swaying bridges. The convoy was a success, with only one truck lost due to a landslide.

On the morning of the Pearl Harbor attack, Chennault asked Neumann to join the AVG, and he accepted without hesitation. The Flying Tigers nicknamed him Herman the German and made him one of their own. In return, Neumann taught the group’s ground crewmen how to keep machines running by improvising when spare parts were scarce— that cow manure made a great radiator sealant, for instance, or that buffalo horn was an acceptable substitute for Bakelite.

When the AVG was disbanded in July 1942, Chennault asked the U.S. secretary of war for permission to enlist Neumann into the USAAF as a staff sergeant. He was subsequently assigned to the 76th Fighter Squadron as chief engineer. That October Chennault told him that the Chinese had captured a Japanese navy Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero, and it was vital that the Allies test-fly and evaluate the fighter. As Chennault pointed out, if anyone could put it into flyable condition it was Neumann.

The aircraft in question had made a forced landing on the beach opposite Hainan Island, in an area under Japanese control, but the Chinese managed to disassemble it and drag it into the woods near an emergency airstrip at Liuchow. The Japanese regularly sent recon planes over that region, but they never spotted anything, as the plane was well camouflaged.

The Zero was in generally good condition, although many parts had been damaged or lost. Neumann had a team of Chinese mechanics and one American working with him. Using hand tools and a charcoal-fired forge, they repaired many parts and replaced others with components salvaged from wrecks.

The team worked on the Zero for two months, and Neumann was impressed with the innovations in what was largely a handcrafted plane. The wings and cockpit area were a single unit. The entire engine assembly was held to the firewall with four nuts. Fuel and oil lines ran into a junction box that could be quickly disconnected. Although it took eight hours to replace a Curtiss P-40 engine, the Zero engine could be removed in 30 minutes. Since eliminating weight was a Japanese priority, there was no armor or self-sealing fuel tanks as well as no self-starter, which would have required a heavy battery.

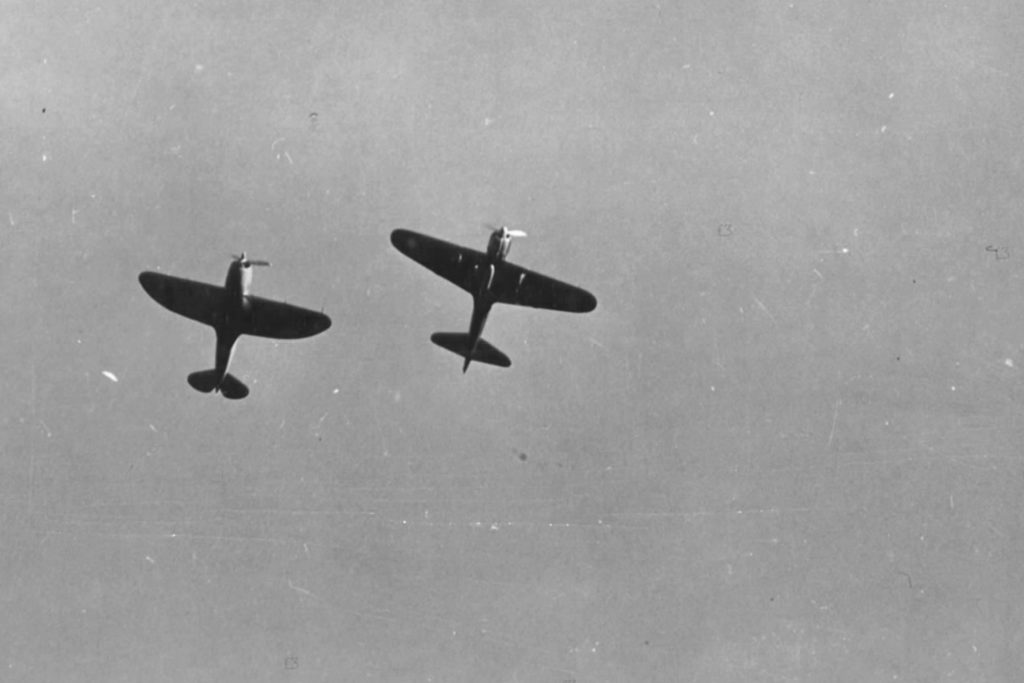

Once assembled, the Zero would have to be flown out to Kweilin quickly, before the Japanese could spot it on the airstrip. To fly it Chennault chose John Alison, the first Army Air Corps ace in China, and later a founder and co-commander of the 1st Air Commando Group. A North American B-25, with Neumann aboard, accompanied the Zero to protect it from possible friendly fire.

Chennault, the American ambassador and hundreds of GIs were waiting when the Zero arrived. The fighter touched down gently, but then the right landing gear suddenly folded up and the plane slewed across the runway. The left gear snapped off, and the Zero dropped down on a belly tank full of 100- octane fuel. Fortunately there was no explosion, but the prop was badly bent, and the wings and fuselage were twisted.

Neumann found that gravel had lodged in the right landing gear during takeoff, preventing it from locking down. Chennault looked over the wreckage and told him to rebuild it. Many years later, during a 1984 interview with the Cincinnati Inquirer, Neumann remembered the crash as “the low point of my life.” But, he continued, “Then I was given the opportunity to reconstruct it again (and it flew perfectly). That showed great confidence in me. It turned into the high point of my life.”

At Kweilin the work was easier, since there was a hangar with electricity and power tools. But when Neumann fell ill with typhus and malaria, work stopped for almost a month while he recovered in a Kunming hospital. When he returned he was still so weak that he directed the mechanics from a cot in the hangar, huddled under blankets and wearing a fur-lined flying suit.

After the job was finished, the Zero was flown to Kunming (this time with the gear locked down), where American pilots test-flew it against U.S. fighters. Its light weight made it highly maneuverable, confirming the tactics Chennault had taught his pilots: Don’t try to dogfight with Japanese fighters; make a pass and dive away.

The Zero was shipped Stateside for technical examination and a war bond tour, while Neumann returned to Chennault’s expanded Fourteenth Air Force. With spare parts still in short supply, he continued to use his imagination and skill to keep the airplanes flying. When tires became scarce, for example, Neumann re placed them with rope wrapped around the wheel rims. One Douglas C-47 flew missions for a week equipped with one rubber tire and one rope substitute.

At one point legendary Flying Tiger Tex Hill needed some North American P-51s for a long over-water flight, but the battle-weary Mustangs were leaking from their oil and coolant radiators. The ever-resourceful Neumann went to a nearby village and bought four old bicycles, cut spokes from the wheels, inserted them into the radiators and sealed them with rubber washers cut from the inner tubes. Every last one of those jury-rigged aircraft returned from Hill’s famous 1943 Thanksgiving Day raid on Formosa.

Neumann’s ability to speak Chinese sparked a request for him to join the Air Ground Forces Resources and Technical Staff, actually a unit of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). He served for 11 months as a member of two-man teams that sneaked into enemy territory to observe the Japanese. If good targets presented themselves, the team directed airstrikes via a hand-cranked radio. They sent coded reports to their base, but when the aircraft were overhead, they spoke to the pilots in the clear.

The teams also reported on activities of the Chinese army, whose operational reports often did not jibe with reality. After one such mission, in October 1944 Chennault ordered Neumann to Washington, D.C., to brief the OSS chief, Maj. Gen. William “Wild Bill” Donovan. Told that Neumann could not travel to the States legally, Chennault responded that it would be done illegally. The FBI met Neumann in New York, but released him when assured by the OSS that he was one of theirs.

Chennault had asked Donovan to get Neumann a direct field commission, and Donovan had his staff look into it. After briefing Donovan, Neumann went on leave for 60 days. During that time he met his future wife, Clarice, who was then working as an attorney for the Justice Department.

Despite everyone’s best efforts, Neumann could not be commissioned, since he was technically an enemy alien. Donovan said he would resolve this absurd situation, even if it took an act of Congress. In May 1945, a bill was introduced in Congress and a year later President Harry Truman signed it: Herman the German was now an American citizen.

Neumann finished the war in China, where he and Clarice married. Upon his return to the States he worked for Douglas Aircraft, but in 1947 he went back to China to help Chennault start an airline. The next time he returned to the U.S.—accompanied by Clarice and dog Mr. Chips—he traveled much of the way by jeep, driving 10,000 miles on rough roads and trails from Thailand to Jerusalem.

Back in America Neumann embarked on a 32-year career with General Electric, where in his early years he invented and developed the variable stator, now used in virtually every jet engine built. It was the first of his eight patents. In the early 1950s, he led the team that developed the J79, a military turbo jet that powered the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter and shattered a series of speed and altitude records.

By the 1960s, GE had 85 percent of the world’s jet engine business, and Neumann was made general manager of its 20,000- employee Flight Propulsion Division. He was widely hailed as one of the most innovative engineers in aviation history, the recipient of many awards, including the 1958 Collier Trophy (for the J79), NASA’s Goddard Award and the French Légion d’Honneur. He retired from GE in 1980, and died in 1997 as a result of complications from leukemia.

In 1984 Neumann published his autobiography, Herman the German: Just Lucky I Guess. No doubt he was a lucky man, but a poster that hung behind his desk at GE may have best summed up his guiding philosophy: “The harder I work, the luckier I get.”

The Gerhard Neumann Museum in Niederalteich, Germany, celebrates Neumann’s life and accomplishments. For more information, see www.f-104.de/english/home_english.html.

Originally published in the September 2009 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.