In May 1968, two small American outposts deep in enemy territory were all that remained of a massive force from the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) that had just been in one of the biggest battles of the war. The division arrived during Operation Pegasus in early April to break the North Vietnamese Army’s siege of the Khe Sanh Marine base, which had been under attack since Jan. 21. After the relief force reached the Marine base on April 8, most of the 1st Cavalry Division troops moved south to the A Shau Valley. But two battalions and associated artillery units in the division’s 2nd Brigade stayed at landing zones Snapper and Peanuts to support Marine regiments that had re-established control of the Khe Sanh base and were going on the offensive against the NVA in the surrounding hills. Before long, wounded and dead from both sides would be scattered around Landing Zone Peanuts in some of the toughest fighting that many of the air cavalry troops would ever see.

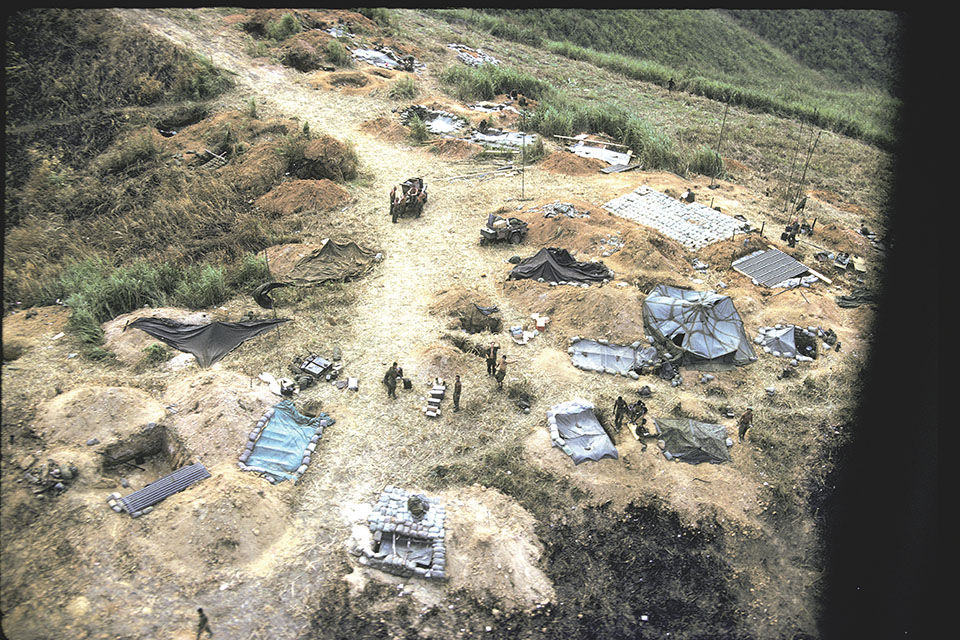

In mid-April, troops of the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment, had been helicoptered to a T-shaped hill, LZ Peanuts, to protect the westward approaches to Khe Sanh. To the east of the hill were a few thousand yards of open plain. To the south were Route 9 and the Lang Vei Special Forces camp that had been overrun about 2½ months before. To the west were Laos and the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Communist forces there wanted to attack Khe Sanh again, but they would first have to wipe out LZ Peanuts.

The 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry, troops constructed defensive positions around the entire perimeter of the landing zone and fortified their widely spaced hootches. They laid coiled barbed wire in some areas of the perimeter and cut down elephant grass around bunkers to provide clear fields of fire.

Stretching out from the main area of LZ Peanuts was a narrow finger of land dotted with 105 mm howitzers and the bunkers of artillerymen in Battery A, 1st Battalion, 77th Artillery Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division.

Around 4:30 p.m. on May 4, 1968—about two weeks after the troops arrived on LZ Peanuts—three enemy artillery rounds landed in the perimeter. One shell hit the ammunition dump containing more than 2,000 rounds of howitzer ammo. The explosions sent the Americans scrambling for cover. By the end of the day, LZ Peanuts had been hit with 21 artillery rounds, killing two soldiers and taking 10 others out of the fight, including Battery A’s Capt. Ron Weiss. With the battery’s commanding officer sidelined and a burning ammo dump still exploding, the diminished ranks of artillerymen left their positions on the narrow ridge and shifted to foxholes on the main hilltop, temporarily abandoning the battery’s six 105 mm howitzers.

As night approached, Lt. Col. Zeke Jordan, in the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry’s operations center on LZ Peanuts, realized that his hill had the full attention of NVA soldiers based 31/2 miles southwest in Laos. Worse, Jordan now had no manned howitzers on the hilltop and only one understrength infantry company, Alpha Company, providing perimeter security.

Only about 150 defenders were still manning LZ Peanuts, while 300 or more North Vietnamese from the 304 NVA Division’s 66th Regiment—two companies of NVA infantrymen and a company of sappers (an elite commando force)—were spread out and hidden on the sides of the hilltop landing zone and at staging areas in the valley below.

Sometime after midnight on May 5, the sappers began to quietly crawl uphill from multiple sides. Their mission was to blast wide gaps in LZ Peanuts’ perimeter so regular NVA troops, running up behind them, could rush through for a close-quarters attack. Wearing only small drab loin cloths and smeared with black soot, the sappers inched through thick elephant grass that sliced at their skin. They hauled satchels filled with explosives and carried folding-stock AK-47 assault rifles. Though some brought medical supplies, most knew their climb would likely be a one-way trip.

Just before 2 a.m., Spcs. David Hosu and Thomas Mullins of Alpha Company’s 1st Squad, 1st Platoon, sat in their underground bunker down the hill, about 200 yards outside LZ Peanuts’ perimeter, where they were on listening-post duty, along with Pvts. Britton Kaur, Terry Misener, Jackie Lee Riley and Don Collier. Kaur and Misener had been perched atop the hootch as lookouts, and it was time for them to be relieved by Hosu and Mullins. Kaur poked his head in an opening in the sandbagged wall to make sure they were awake. “All right, damn it, I’m up,” an aggravated Hosu hissed. Suddenly two trip flares were set off just beyond the perimeter, illuminating Kaur and Misener’s figures outside the bunker. Both men immediately grabbed grenades off their flak jackets, pulled the pins and tossed the explosives in the direction of the flares. The blasts were accompanied by the screams of enemy troops. Another blast went off 10 feet in front of Kaur and Misner.

“Who the hell threw that grenade?” Kaur yelled.

“What grenade?” replied someone inside the bunker.

Realizing now how close the invaders were, Kaur grabbed the PRC-25 radio in the bunker to contact Capt. George Kish at Alpha Company’s hootch, about 350 yards away at the landing zone. “We have definite movement out here,” Kaur said. “They’re trying to get inside our perimeter.”

While Kaur talked into the headset, Hosu picked up an M79 grenade launcher and exited the bunker, followed by Mullins with an M16 rifle. Meanwhile, Riley and Collier, still inside the bunker, began tearing down sections of the walls to create better observation points. For several minutes, the two sides exchanged grenades and satchel charges. Then, as abruptly as it had started, the action subsided at the listening post. But small-arms fire and explosions intensified on the higher ridge behind them—LZ Peanuts was under attack.

Battalion commander Jordan relayed an urgent message to the 2nd Brigade headquarters at LZ Snapper, just across the valley: “LZ Peanuts is sitrep red. I say again, LZ Peanuts is sitrep red,” code for Situation Report Red, used to indicate that a base was under direct attack. Jordan said the enemy was inside the wire, attacking with satchel charges and small arms on the east, northeast and southwest perimeters. Over the next few hours, waves of sappers and NVA soldiers continued to assault the perimeter.

Meanwhile, 1st Lt. Mike Maynard, who took over for Weiss and became acting commander of LZ Peanuts’ artillery, stood outside his bunker and radioed LZ Snapper. Maynard asked the artillery unit there—Battery A, 1st Battalion, 30th Field Artillery Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division—to shoot illumination flares over the besieged landing zone so the base’s defenders could see the attacking enemy.

On the southern perimeter, Pvt. Scott Thompson of Alpha Company’s 1st Platoon was in his bunker when the illumination flares fired from LZ Snapper exploded in the sky above Peanuts and lit up NVA locations below. To his left, the sound of gunfire near the howitzers intensified. To his right, Staff Sgt. Carlyle Guenther ordered an M60 machine gun to fire bullets with red tracer tails over the hill.

As Thompson peered out the slit of his bunker into complete blackness, a burst of light from an illumination flare revealed a nearly naked man moving in a crouched run up the hill, bypassing his position. Incredulous, Thompson wondered how the enemy got into his perimeter. He sprawled out of his bunker and aimed his M16 at the passing sapper. Before he could fire, a small sizzling explosive charge landed at his feet.

Instinctively, Thompson leaped head-first into a slit trench filled with human excrement, and the charge’s blast blew above him. He rolled over, and another charge landed on his chest. Thompson hurriedly jumped out of the trench and slid face-first across the ground as the second explosive went off, blowing dirt and human waste everywhere. After pressing himself up, he began checking his M16. Then something hard hit him between the shoulders. A third charge had just been thrown at him. Thompson rolled back into the relative safety of the stinking slit trench he had just exited.

Pvt. Michael Huff of Alpha’s 3rd Platoon worked his way to the perimeter near Thompson as explosives went off all around. The concussion from one charge temporarily paralyzed Huff and knocked him out. He woke up in a foxhole with a baseball-sized chunk of meat missing from his neck. NVA soldiers were standing and talking over the foxhole, unaware that he was still alive. After the feeling in his extremities returned, Huff grabbed his M79 grenade launcher, leveled it between the shoulder blades of a retreating NVA soldier and squeezed the trigger.

Artillery commander Maynard, holding a 25-pound radio, was making his way toward 1st Sgt. Charles Marshall at LZ Peanut’s fire direction center, which had controlled the artillery battery’s firing before the ammo dump explosion ended the action there. As Maynard ran, small-arms fire was snapping through the air, and one round struck the radio, nearly forcing the lieutenant to drop it as he reeled backward. “Damn it, there goes the radio!” he thought, not realizing that the hunk of metal he carried had just saved him from a gruesome wound.

When Maynard found Marshall, he asked if the sergeant had another radio that could be used to adjust the incoming illumination if necessary. “No, sir,” Marshall replied, but added that 1st Lt. Ed Cattron, down the hill, might have one. Maynard decided to make a dash for Cattron’s position. Crouching anxiously by the now-defunct fire direction center, Maynard waited for the next illumination round from LZ Snapper. After the flash of light, he sprinted 50 yards to Cattron’s bunker, yelling “friendly, friendly.” As he slid into the bunker, a winded Maynard could only say, “I hear you have an extra radio.”

Instead of answering, Cattron motioned toward Maynard’s abandoned howitzer positions. “I think there are [NVA] regulars out there,” he blurted. Both officers watched dozens of uniformed NVA soldiers swarming through the empty artillery gun pits. “They don’t know we have contracted our perimeter,” Cattron said. “Open that box and start rolling those grenades out there.”

Up on the hill, Jordan was outside the battalion operations center being treated for a leg wound when 1st Lt. Charles Brown approached him. “Col. Jordan, our perimeter near the battery is breaking apart,” Brown said, frantically. “I’m going to grab some men and try to fill in the gap.” Receiving a nod of approval, Brown spun around and headed toward the fire direction center.

Rushing down the slope, Brown passed several soldiers, nearly lifting them up with one arm, and threw them in the direction of the encroaching NVA troops. “They’re busting through down there,” he shouted. “Plug up the hole!” Brown climbed on top of the fire direction center’s roof, overlooking the abandoned battery position, and saw the enemy moving quickly up the hill. As he directed his men into firing positions, a piece of jagged metal struck his extended arm. Brown dropped to one knee but quickly grabbed his wound, steadied himself and continued to command his men, sending them to various positions to protect and tighten the base’s collapsing perimeter.

All across LZ Peanuts, others were taking similarly frenzied actions to stop the NVA advance. Guenther was coordinating the adjustment of the western perimeter when a bullet ripped through the staff sergeant’s chest. He slumped to his knees, lowered his head and died.

Meanwhile, Brown continued to run between the battalion operations center and the perimeter overlooking the abandoned battery. On one of his trips to the perimeter, he collided with an NVA sapper. The two foes wrestled to the ground, scratching and clawing at each other as they rolled downhill. Brown, a former high school wrestler, managed to work his hand up to the sapper’s face and plunge his thumb into the man’s eye. The sapper screamed in pain and pushed himself loose of the American’s grip, escaping into the darkness.

Brown continued on to Cattron’s bunker overlooking the battery and asked for a situation report. Cattron said North Vietnamese regulars and sappers were moving freely through the battery, trying to destroy the howitzers. “There are no friendlies between us and them,” he added. It was roughly 4 a.m., just one hour before sunrise. Suddenly the already-heavy small-arms fire intensified.“They are making another push!” Brown yelled.

Cattron pointed out enemy soldiers hiding behind jeeps about 50 yards away. Realizing the need for immediate action, Brown and Cattron charged the jeeps. Screaming, firing their M16s and throwing grenades, while satchel charges were thrown at them, they covered the 50 yards in a few seconds.

After several minutes of intense close-quarters fighting, Cattron shouted at Brown to pull back to the bunker. “I’m calling in Blue Max support,” he said, a reference to the nickname for the rocket-armed helicopters of the 20th Field Artillery Regiment (Aerial Rocket), 1st Cavalry Division.

Cattron grabbed the remaining PRC-25 and radioed LZ Peanuts fire support liaison officer, Capt. Duke Wheeler of the 1st Battalion, 77th Artillery. “I need immediate Blue Max support on this east finger with the battery on it,” Cattron said. “As you come in from the north, you will see a line of jeeps and trailers. Use the jeeps as your bearing and hose down the hill to the southeast. Bad guys all over that ridge.”

With daylight still 30 minutes away, artillery officer 1st Lt. Jim Harris at LZ Snapper radioed battery commander Maynard on Peanuts with distressing news: “We are running low on illumination rounds. Do you copy?” Around 4:30 a.m., the Snapper crews fired their last illumination round and watched it drift across the valley until fizzling out. Harris exhaled audibly and hung his head in despair. Then he heard the distant hum of aircraft engines.

Over the radio came the call: “Peanuts Control, Peanuts Control, this is Spooky. We are coming on station. Where do you need us?” The twin engine Air Force Douglas AC-47 Spooky arrived overhead. The aircraft could drop powerful MK-24 flares—each able to produce brilliant illumination for up to three minutes—and was equipped with three 7.62 mm miniguns, each capable of firing 6,000 rounds per minute.

While the AC-47’s flares illuminated the attacking North Vietnamese hordes, the plane’s deadly miniguns shredded the invaders. At a 2005 reunion, Harris recalled the dramatic moment Spooky arrived: “No Hollywood script could have been more dramatically written,” he said. “At that instant…Spooky lit up the sky! The roar that erupted from LZ Snapper was like Lambeau Field [home of the Green Bay Packers] on a Sunday afternoon in October.”

As sunlight reached LZ Peanuts, the sounds of war diminished and curious heads began to pop up from behind blast walls and foxholes to survey the wreckage of war strewn across the hill. The six men on the dangerously exposed listening post outside LZ Peanuts inspected their position and solemnly hiked back up the hill. Seven of their 11 trip flares had been triggered, and only one grenade was left between them.

The rest of Alpha Company began the grisly task of searching dead bodies and gathering weapons. Sleep-deprived and skittish from a night of intense fighting, most of the troops were on edge.

By 7 a.m., they had discovered 30 North Vietnamese bodies in and around the base, many blood trails in all directions and a substantial cache of weapons, including 15 AK-47 rifles, three B-40 rocket launchers, a radio and numerous satchel charges and grenades. It was clear the attack on LZ Peanuts had been a well-coordinated assault that had likely taken weeks to prepare.

As ground troops continued mop-up operations around the perimeter, a stream of medevac helicopters made several flights to evacuate the two dozen wounded. The injuries included burns, burst eardrums, shoulder wounds, broken legs, gunshot wounds and bayonet wounds. Numerous infantrymen with “relatively minor” wounds choose to remain alongside their comrades at the base.

The wounded soldiers were lifted off the hill by 6:30 a.m., and the task of moving the dead followed. As Wheeler, the fire support liaison officer, was helicoptered out, he looked down through the chopper’s open doorway and saw a line of 11 poncho-covered American bodies near the helipad. Two hours later, the remaining infantrymen of the 1st Battalion learned that they would be flown off the landing zone, followed by the destroyed howitzers.

On May 6, the Americans destroyed their bunkers and left LZ Peanuts to the jungle. Two days later, most of the grunts in the 2nd Brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division were helicoptered to a location about 30 miles northeast of Peanuts and 5 miles south of the Demilitarized Zone to participate in a joint operation with the Marines. Although the fight for LZ Peanuts had been won, combat for the 1st Cavalry Division continued.

—John McGuire, a forester and wildlife biologist in South Alabama, has spent years researching the 1st Cavalry Division, in which a family friend served.

This article was published in the December 2018 issue of Vietnam.