The woman who would one day become one of the best-known test pilots of the Third Reich was born on March 29, 1912, into an upper-middle-class family in Hirschberg, Silesia. From early on, Hanna Reitsch was an intense, determined and intelligent individual. She became fascinated with flying at a young age, reportedly attempting to jump off the balcony of her home at age 4 in her eagerness to experience flight. Looking back on her childhood, she wrote in her 1955 autobiography The Sky My Kingdom: ‘The longing grew in me, grew with every bird I saw go flying across the azure summer sky, with every cloud that sailed past me on the wind, till it turned to a deep, insistent homesickness, a yearning that went with me everywhere and could never be stilled.’

By the time she was 14, she had set her sights on becoming a flying missionary doctor in Africa. It was a dream that seemed likely to please both her authoritarian ophthalmologist father, a Protestant, and her devout Catholic mother. During her teens she studied the writings of Ignatius of Loyola to discipline her mind and develop highly focused concentration. She made a pact with her father that if she did not mention going to a glider school until she had completed her secondary schooling, she would then be allowed to learn how to fly. Thanks to her determined silence, she managed to fulfill that pact. On the condition that she would also take a course in what was then called “domestic science,” she was allowed to go to the Grunau School of Gliding.

Reitsch had the good sense to realize that a domestic science course would serve her well in the primitive conditions she would likely encounter in Africa, and she dutifully undertook her studies at the Colonial School for Women at Rendsburg. There, in addition to her other lessons, she was taught how to care for domestic animals as well as to ride and shoot.

For young Reitsch, however, the real goal remained flying. Despite the derision of the male students as well as instructors — she was the only woman in her class — she was the first class member to pass the “A” level beginning course. Authorities were so taken aback when they learned of her rapid progress that they made her retake the test — which she once again passed. She went on to pass the “B” and “C” tests before beginning medical school at the University of Berlin.

While studying medicine, she also sought permission from her parents to continue with flying lessons in Staaken. She later recalled, “I managed to convince them that for my career as a flying doctor in Africa it would be necessary for me to learn to pilot engined aircraft.”

She soon realized that most pilots knew little if anything about the engines of their planes. That seemed to her to be like a doctor who knew nothing about the heart. Never afraid of hard work or dirty hands, she started hanging out with the mechanics at the flight school and worked herself into their favor as they realized she was serious about learning about airplane engines.

The mechanics gradually gave her more challenging jobs. One Friday, the master mechanic pointed to a worn-out engine and told her that she could have it to take apart and put back together again by the following Monday. She did just that, later recalling, “on the Monday morning, with torn and bleeding hands and covered from head to foot in oil and grime, I was able to show the foreman the reassembled engine.” By doing repairs, helping out with chores, and polishing and moving airplanes, she also managed to eke her way through flight school. She demonstrated superb piloting skills, even doing stunt flying for motion pictures.

While attending powered flight school, Reitsch realized that a missionary doctor needed to know how to drive an automobile. She had no money for driving-school tuition but solved that problem in typically creative fashion. She began to visit with workmen who were operating earthmoving machinery near the airstrip. She would do the same dirty jobs they did and ask them questions about clutches, brakes, chokes and carburetors. They finally let her drive some equipment.

In 1934, Reitsch traveled to Brazil and Argentina as part of a German research expedition to test-fly gliders in extreme thermal conditions. Her growing reputation as a pilot resulted in her leaving medical school and accepting an invitation to become an experimental glider test pilot at the Deutschesforschungsinstitut fur Segelflug (DFS), the German Research Institute for Sailplane Flight at Darmstadt. She became involved in flight testing to address problems of stability and control and structural vibration. She also test-flew the first glider seaplane and evaluated the capabilities of new glider catapult mechanisms.

In 1936, Reitsch met Ernst Udet, head of the Technical Branch of the Ministry of Aviation and the highest-scoring German fighter ace to survive World War I. At the time, she was working on the development of dive brakes for gliders. After demonstrating the use of dive brakes in a vertical dive before Udet, other Luftwaffe generals and German aircraft designers, she was awarded the honorary rank of Flugkapitän, the first woman ever so honored. In 1937, she was designated as a Luftwaffe civilian test pilot, a post she would hold until the end of World War II. Reitsch and Udet shared a passion for flying and developed a close professional relationship that lasted until Udet, depressed by the crushing demands of his job, committed suicide in November 1941.

Reitsch also became close to another former fighter pilot and rising Luftwaffe star, Robert Ritter von Greim, a Bavarian ace who had scored 25 aerial victories during World War I and had been awarded a knighthood and the coveted Orden Pour le Mérite. Greim had been appointed by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring to be the first squadron leader of the new Luftwaffe. Along with Udet, Greim witnessed Reitsch’s high-speed dive brake tests, which he found very impressive.

In the years leading up to WWII, Reitsch made a name for herself on the international flying circuit. In May 1937, she became one of the first Germans to fly a glider over the Alps. That same year, she set a world long-distance record and won the National Soaring Contest — the only woman entrant. She also traveled extensively, to Africa and to the United States. By the summer of 1937, Reitsch had completed her test pilot duties in the development of dive brakes. After Udet appointed her a civilian test pilot at the primary Luftwaffe research station at Rechlin, she was allowed to fly almost anything she could lay her hands on, which included most of the high-performance aircraft in the Luftwaffe inventory. Rather than seeing her work with these aircraft as a prelude to what she would one day characterize as “the tragedy to come,” at the time she chose to view them as guarantors of peace. She later wrote: “Stukas — bombers — fighters! Guardians at the portals of Peace! And in this spirit I flew them, each time in the feeling that, through my own caution and thoroughness, the lives of those who flew after me would be protected and that, by their existence alone, they would contribute to the protection of the land that I saw beneath me as I flew. … Was that not worth flying for?”

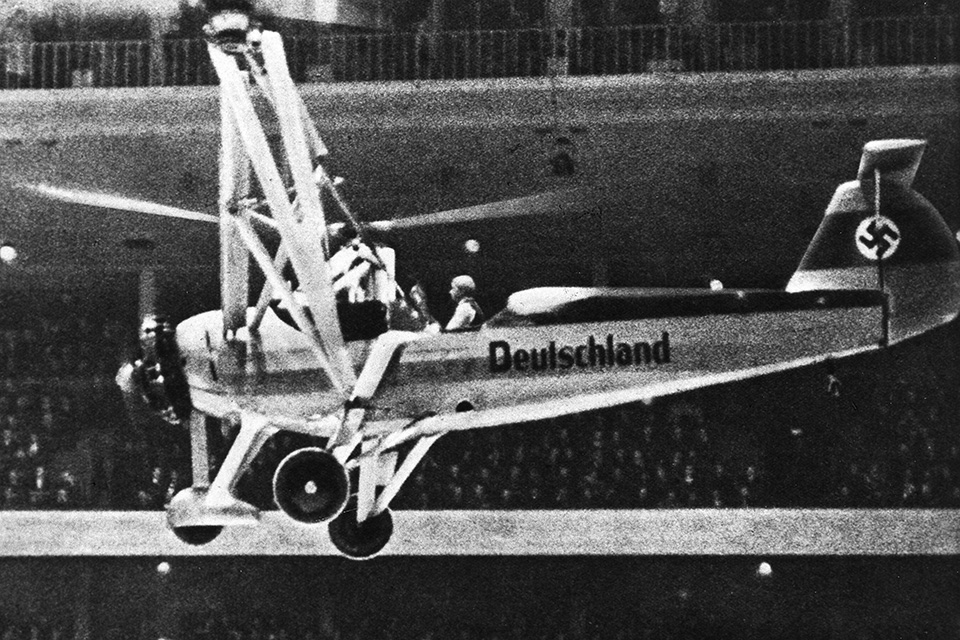

In February 1938, at Udet’s bidding, Reitsch would become the first person to fly a helicopter, the Focke-Achgelis Fa-61, inside a building, Berlin’s Deutschlandhalle. She had previously been called on to demonstrate the Fa-61 to American aviation legend Charles Lindbergh at Bremen, whom she afterward described as a man “whose simplicity of manner won all hearts wherever he went.” She also became the first woman to be awarded the Military Flying Medal, thanks to her helicopter flights. But the prospect of appearing as what she characterized a “variety artiste” in Berlin appalled her, even though Udet’s goal was legitimate: to prove before an international audience that the helicopter was fully controllable. Reitsch dutifully completed a series of indoor demonstrations. But as she later wrote, “Exactly how deep an impression my flight with the helicopter had made on the world at large I was not to realize till many years later, in 1945, [when] I came across an American soldiers’ magazine. … The first thing that caught my eye was my name and then I saw that it contained an article describing in popular terms my flight with the helicopter.”

War clouds were beginning to gather, but there would be time for at least one more foray into the world of international sports flying in August 1938, when Reitsch visited the United States to make an appearance at the International Air Races at Cincinnati. Friends and family had prepared her to dislike Americans, but she enjoyed the trip immensely, later writing, “there was much in the American way of living that seemed to me worthy of imitation.” She did encounter some anti-German sentiment, but her demonstration of Hans Jacobs’ aerobatic glider, the Habicht (goshawk), in Ohio garnered frenzied applause and invitations to appear elsewhere. At that point, however, she was summarily recalled home by her government.

In 1939, Reitsch suffered through a three-month bout with scarlet fever, followed by muscular rheumatism. On recovering, she went right back to work, becoming involved in the development of large cargo-, troop- and fuel-carrying gliders. The work was largely abandoned after the 180-foot wingspan Messerschmitt Me-361 Gigant (giant) crashed and killed the pilots of its three Me-110 tow planes, the Gigant‘s six-man crew and 110 troops in the glider. She later undertook a very dangerous assignment involving the development of barrage balloon cable shears for German bombers.

In 1942, the operational version of the single-seat rocket-powered bomber interceptor known as the Komet, the Messerschmitt Me-163, was undergoing testing at the research center at Augsburg. Reitsch became determined to fly this bullet-shaped plane, driven by a liquid-fueled Walther rocket engine. By the autumn of 1942, she managed to finagle three flights in the prototype, Me-163A, as well as a flight in the first production model, the Me-163B.

Reitsch’s last flight in the Me-163B nearly ended her life. The Komet‘s cockpit proved to be arranged so that someone her size could not easily fly the plane. It was hard to reach the rudder pedals, and she was also forced to dispense with the shoulder harness and lean forward to operate the controls.

The flight proceeded uneventfully until Reitsch moved the control to drop the takeoff undercarriage. The plane immediately began to shudder and became nearly impossible to control. Her hand radio had stopped working, and it was not until she saw one of her tow plane crewmen waving a handkerchief while the pilot raised and lowered its landing gear that she understood that the Me-163’s dolly undercarriage had not fallen away as it was designed to do. Despite her best efforts and those of the tow plane pilot, no maneuver would dislodge the undercarriage.

Reitsch decided to try to land the plane. She nearly succeeded, but at the last instant the aircraft stalled and crashed into a plowed field just short of the runway. She survived the crash but suffered severe injuries. Her nose was nearly sheared off, her skull was fractured in four places, two facial bones were fractured, and her upper and lower jaws were misaligned.

Four days after that accident, in tribute to her skill and bravery in this and other developmental work, Reitsch was awarded a special diamond-encrusted version of the Gold Medal for Military Flying by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring. She was also later awarded the Iron Cross First Class.

After five months in the hospital and much plastic surgery, Reitsch was discharged — though at first she was still plagued with spells of dizziness and spatial disorientation. Without medical permission, she began to fly again, starting with gliders and graduating to powered aircraft and strenuous aerobatic maneuvers until she was satisfied that her flying skills were as good as they had ever been. In August 1943, 10 months after her accident, her surgeon gave her medical clearance to return to normal activities.

Reitsch followed the Me-163 development group to its site at Peenemünde-West. There, she learned the details of the pulse-jet powered V-1 buzz bomb and the V-2 ballistic missile programs run by General Walter Dornberger and Wernher von Braun. She survived unscathed the first Allied bombing raid on the complex, which left most of Peenemünde a pile of rubble. Shortly thereafter, when she met with friends in Berlin at a luncheon, the conversation turned to a discussion of what they could do to save Germany from what was now seen as a slide into defeat. The group decided to propose aerial strikes on strategic Allied targets carried out by suicide bomber pilots, a concept dubbed Operation Self Sacrifice.

Despite her association with the highest levels of Nazi officialdom, Reitsch was apparently slow to recognize the ruin into which they were leading the country. When she resumed her Me-163 flight test duties following her accident, she was invited to a luncheon with Göring. During the meal she was appalled to realize that the Reischmarschall was apparently living in a dream world. He believed that the Me-163 was in mass production and would soon deliver the Fatherland from the scourge of the Allied 1,000-plane bombing raids. Worse yet, when Reitsch tried to correct Göring’s misperceptions, he made it clear that he would not listen to any contrary view and abruptly left the room to go and play with his children.

Reitsch’s return to the Me-163 project, now located at Bad Zwischenahn, was marred by the project director’s refusal to allow her to fly it again. Despite her howls of protest, there was no reversal of this position. She withdrew from the project when her longtime friend Greim approached her with a request to visit him on the Russian Front in an attempt to boost the morale of the troops. During that trip, Reitsch’s understanding of the bloody realities of war was driven home with a brutal vengeance. This new reality fueled her determination to press for the formation of a corps of suicide pilots.

Late in 1943, Reitsch took the opportunity to discuss Operation Self Sacrifice directly with Hitler when she was invited to a ceremony at Berchtesgaden to receive her Iron Cross First Class. He parried her efforts to talk about a suicide bomber plan by launching into a long, rambling monologue about how the new twin-engine Messerschmitt Me-262 jet fighter would save the day. Reitsch pressed her case and finally gained the Führer‘s reluctant permission to go ahead with experimental work only — with the proviso that he must be spared the details.

Operation Self Sacrifice got underway with a plan to use the Me-328B, already in the prototype stage, as a parasitic “Sacrificial Fighter.” Reitsch and other pilots carried out experiments with the Me-328 flying under its own power as well as functioning as a glider to be launched from a Dornier Do-217E twin-engine bomber. These plans were abruptly terminated when an Allied bombing raid wiped out the factory in which the prototype Me-328s were being built. This was probably just as well, since the Me-328 had severe flaws.

The planners then adjusted their sights, hoping to use the V-1 guided glider bomb then entering operational status. Seventy of the V-1s equipped with cockpits for piloted flight were ordered, to be built by Fieseler and designated as the Fi-103 Reichenberg. This manned version of the V-1 proved easy to fly but glided like a brick and was tricky to land on its skid because of its very high landing speed and tendency to ground-loop.

One factor that caused problems with the V-1 as a cruise missile was related to vibrations imparted to the airframe by its power plant. The pulse-jet engine developed thrust through very closely placed machine gun-like explosions, thus the nickname “buzz bomb.” In the course of test flights, Reitsch was able to identify this problem, and she may also have contributed to improving the V-1’s accuracy.

In the Fi-103 test plane, the cockpit was directly in front of the engine intake. It was assumed that in the event of an emergency during test flights, the pilot would be able to open the canopy and bail out. In point of fact, it is more than likely that the exiting pilot could not survive if the engine was running. Two of the seven Fi-103 instructors were killed, and four were injured. Reitsch was the only one of the group to survive the test program without injury.

Reitsch was designated as an instructor of the volunteer pilots in what was called the Leonidas Squadron (formally the 5th Staffel of Kampfgeschwader 200), presumably named after the heroic Spartan general who, in 480 B.C., with a cohort of about 1,000 warriors, fought to the death to save the rest of Greece from invading Persians. She encountered numerous difficulties with the project, thanks to the indifference of her high-ranking Nazi friends. The prevailing attitude among them amid the disastrous military situation in late 1944 was that the very idea of suicide pilots was “un-German” and that it went against the grain of the German psyche. The last months of Reitsch’s wartime service involved flying wounded soldiers into hospital airstrips, carrying urgent dispatches by air and surveying air routes into the rubble of Berlin.

On April 25, 1945, Greim told Reitsch she must fly with him to Berlin for a meeting with Hitler. As a result of a proposal by Göring to take over leadership of the country, Hitler had ordered Göring arrested, and he intended to appoint Greim the commander in chief of the Luftwaffe.

The last leg of their trip to the Führerbunker in devastated Berlin was made in a little Fieseler Fi-156C Storch (stork), with Greim at the controls and Reitsch crouched behind him. Flying through a hail of Soviet anti-aircraft fire, the plane was hit in the engine and fuel tank. An armor-piercing bullet smashed Greim’s right foot, and he passed out. Reitsch managed to successfully land the Fieseler on the boulevard before the Brandenburg Gate, and they both made it to Hitler’s bunker, where they stayed for two days. Ordered by Hitler to flee Berlin in the final hours of the Russian assault on the city, Greim and Reitsch escaped in an aircraft hidden near the bunker.

On the morning of May 9, Reitsch delivered Greim to a hospital at Kitzbühel. Based upon information provided by a British officer, she was taken into custody by the Americans that same afternoon. After extended incarceration and interrogation by intelligence personnel — in part because she had been rumored to have flown Hitler to freedom — Reitsch was exonerated of guilt from war crimes. She was finally released from prison after 15 months.

During her time behind bars, Reitsch discovered that her parents had committed suicide rather than be taken prisoner by the Russians. Greim, too, on learning that the Americans were going to turn him over to the Russians, killed himself in Salzburg on May 24, 1945. His last words before swallowing potassium cyanide were reportedly, “I am the head of the Luftwaffe, but I have no Luftwaffe.”

For some years after the war, the Allies forbade Germans from participating in gliding. Reitsch eventually began lecturing in Europe, but she was banned from flying in competitions in England until 1954. In 1959, she represented Germany on a trip to deliver a glider to Delhi, where she became friends with Indira Gandhi. She opened a gliding school in Ghana in 1962, and also revisited the United States, where she met Igor Sikorsky and Neil Armstrong.

Throughout the remainder of her life, Reitsch remained a controversial figure, tainted by her ties — both real and suppositious — to the dead Führer and his henchmen. The circumstances surrounding her 1945 sojourn in Hitler’s Berlin bunker especially haunted her. In a postscript to a new edition of her memoirs, published shortly before her death from a heart attack in 1979, she wrote that “so-called eyewitness reports ignore the fact that I had been picked for this mission because I was a pilot and trusted friend [of Greim’s], and instead call me ‘Hitler’s girl-friend’… I can only assume that the inventor of these accounts did not realize what the consequences would be for my life. Ever since then I have been accused of many things in connection with the Third Reich.”

During WWII, Hanna Reitsch devoted her energy and skill to what she considered to be German nationalism as distinct from Nazism, believing she owed her allegiance to Germany, not to Hitler. But above all, throughout her life, she remained passionately committed to aviation, especially gliding. She set more than 40 records during her lifetime, many of them in gliders. She wrote, “Powered flight is certainly a magnificent triumph over nature, but gliding is a victory of the soul in which one gradually becomes one with nature.”

This article was written by R.E. Van Patten and originally published in the May 2006 issue of Aviation History.