By the mid-18th century archrivals Great Britain and France had each laid claim to the Ohio Valley, a swath of fertile bottomland stretching nearly 1,000 miles from the Allegheny Mountains west to the Mississippi River. They based their respective claims on surveys, settlement, land grants, treaties and purchases from various Indian tribes.

For the British colonies of Pennsylvania and Virginia, as well as the London-based Ohio Co., the river valley represented a natural corridor for westward expansion. The French, on the other hand, envisioned it as a link between the New France colonies of Canada and Louisiana. Seeking to contain British encroachment, French troops garrisoned the valley in 1753, prompting a global conflict known in North America as the French and Indian War and elsewhere as the Seven Years’ War (1754–63).

Prompting the conflict in part was the 1748 formation of the Ohio Co., organized by British and Virginian investors who had obtained from the Crown a 200,000-acre land grant in the upper Ohio Valley, provided its directors could settle 100 families in the region within seven years. Tensions mounted in the spring of 1753 when French troops marched south from Fort Niagara on Lake Ontario, driving out British traders and building forts. In 1753 Virginia Lt. Gov. Robert Dinwiddie—an Ohio Co. investor—learning the French had built Fort Presque Isle on Lake Erie and Fort LeBoeuf some 20 miles farther south, sent a militia party under Major George Washington to warn the French to withdraw, a request they politely refused. In January 1754 Dinwiddie sent another force of militiamen to build Fort Prince George at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela (aka the Forks of the Ohio, the site of present-day Pittsburgh). They had barely finished when French troops arrived, expelled the Virginians, razed the fort and built a larger garrison named Fort Duquesne, after the governor-general of New France.

In March 1754 Dinwiddie promoted Washington to lieutenant colonel of the newly formed Virginia Regiment and sent him with two companies of militia to defend British claims on the Forks of the Ohio. On May 24 Washington made camp at Great Meadows (present-day Farmington, Pa.), oddly referring to the marshy ground as “a charming field for an encounter.” Three days later a friendly Mingo chief known as Tanacharison, or Half King, sent word of a French camp in the vicinity, and Washington set out with 40 men to find it. Directed to the site by Half King’s scouts, the party ambushed the camp, killing 10 of the Frenchmen—including their commander, Joseph Coulon de Jumonville—and taking 21 prisoners. The Virginians suffered only one man killed and two wounded.

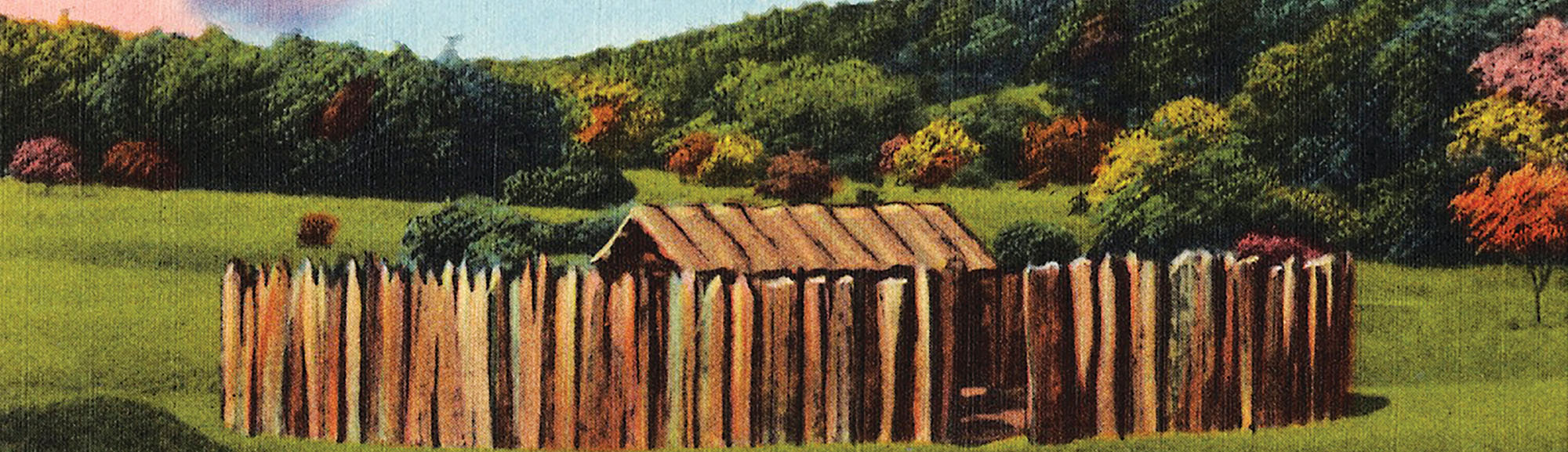

On the accidental death of regimental commander Joshua Fry on May 31, Dinwiddie promoted Washington to colonel and gave him command. Washington promptly fortified Great Meadows with a log stockade he named Fort Necessity. The rest of the regiment, toting supplies and nine small cannons, marched in on June 9, giving Washington about 300 troops. A few days later 100 men of Captain James Mackay’s Independent Company of regular British troops arrived from South Carolina. Unfortunately for Washington, his Indian allies, anticipating a significant French counter-attack, bowed out of the coming fight. While the South Carolinians remained at Great Meadows, Washington and the Virginians marched out to resume work on a road to Redstone Creek on the Monongahela, a stepping-stone to the Ohio. But reports of an approaching force of French troops and allied Indians from Fort Duquesne induced Washington to return to Great Meadows on July 1.

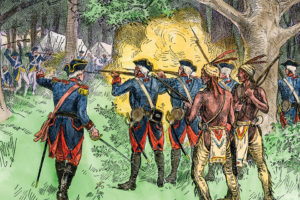

Early on July 3 the 600 Frenchmen and 100 warriors took up positions in the woods around Fort Necessity. Washington pulled his men back within the stockade and its surrounding entrenchment, a decision that proved ill advised as the day’s fighting progressed. A heavy rain flooded the marshy ground and fouled the militiamen’s powder as French fire from elevated and sheltered positions took a heavy toll. In the early evening the French commander, Captain Louis Coulon de Villiers (half-brother of Jumonville), offered the beleaguered British a truce in order to discuss their surrender. Near midnight, after hours of negotiation, both Washington and Mackay agreed to the French terms. It marked the only time in Washington’s long military career he ever surrendered to an enemy.

Early on July 3 the 600 Frenchmen and 100 warriors took up positions in the woods around Fort Necessity. Washington pulled his men back within the stockade and its surrounding entrenchment, a decision that proved ill advised as the day’s fighting progressed. A heavy rain flooded the marshy ground and fouled the militiamen’s powder as French fire from elevated and sheltered positions took a heavy toll. In the early evening the French commander, Captain Louis Coulon de Villiers (half-brother of Jumonville), offered the beleaguered British a truce in order to discuss their surrender. Near midnight, after hours of negotiation, both Washington and Mackay agreed to the French terms. It marked the only time in Washington’s long military career he ever surrendered to an enemy.

The following morning the Virginian-British force—which had suffered 31 dead and 70 wounded—was permitted to withdraw with the honors of war, keeping their baggage and personal weapons but surrendering the cannons. The French, who had lost just three dead, burned Fort Necessity and returned to Fort Duquesne. It took another four years and two additional campaigns—the disastrous Braddock’s Defeat and wildly successful Forbes Expedition—for the British to finally claim the strategic Forks of the Ohio.

Congress established Fort Necessity National Battlefield [nps.gov/fone] in 1931, and preliminary archaeological excavations prompted construction of a diamond-shaped recreation of Washington’s stockade on the original site the following year. However, a follow-up survey in the early 1950s proved the fortification to have been circular, and work crews modified the structure to its current, more accurate reconstruction. Open daily from sunrise to sunset year-round, the visitor center is off U.S. Highway 40 in Farmington.

First published in Military History Magazine’s January 2017 issue.